90 Workshop Three : Sing, Muse

Download a Word Doc of Workshop 3 here

General Instructions: (10 minutes to introduce yourselves, check in, and read instructions)

For this workshop, you’ll be organized in a Zoom Breakout Room with a group of approximately four students. Once you have landed in your Breakout Room, please take a few minutes to introduce yourselves. Select one person to be the timekeeper. This person should keep the group moving along according to the time allotments on the worksheet. This job is crucial, since without it, the group will not complete the experience which the worksheet is designed to bring about. You will not need a scribe today; everyone is encouraged to take notes, as we will return to your answers to today’s questions in our subsequent discussion of the Iliad.

Although we must use the internet in order to meet, please refrain from using a search engine (e.g. Google) to look up answers to questions. If a question arises during discussion that you cannot answer without external research, please bring your question back to the seminar for discussion and/or use it as a writing prompt and do your research outside of class.

1. Composition & Performance (10 minutes)

Originally orally composed and recited in performance contexts over several generations from, perhaps, the late-ninth through early-eighth centuries (ca. 850-725 bce), the Homeric poems (both the Iliad and the Odyssey) were written down in the late-eighth or early-seventh centuries (ca. 725-675 bce). The written composition of the poems coincided with the development of the Greek alphabet and writing. For subsequent generations — through the archaic and classical periods (750-490 and 490-323 bce, respectively) — the Homeric epics were widely performed, read aloud, and memorized, and so they were deeply familiar to many Greek-speaking peoples. Please discuss the questions below, which ask you to think about the significance of the poem’s orality.

Please discuss:

Looking back over what you’ve read of the poem so far, do you see any indications of “orality” in the poem? What might you expect to see in a pre-literate, or performance-oriented, rather than strictly literary, composition?

Given that the Iliad evolved over several generations before it was written down, who is the author of the poem?

Why might the authorship (and mode of composition) of the poem matter to us, in a course that centers the topics of gender and sexuality?

2. In the beginning… (10 minutes) Please review the first seven lines of the Iliad, provided here in Greek with my own translation (which you may compare with Alexander’s).

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος

οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί᾽ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε᾽ ἔθηκε,

πολλὰς δ᾽ ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς Ἄϊδι προΐαψεν

ἡρώων, αὐτοὺς δὲ ἑλώρια τεῦχε κύνεσσιν

οἰωνοῖσί τε πᾶσι, Διὸς δ᾽ ἐτελείετο βουλή, 5

ἐξ οὗ δὴ τὰ πρῶτα διαστήτην ἐρίσαντε

Ἀτρεΐδης τε ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν καὶ δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς.

Anger – sing, goddess, the deadly rage of Achilles, son of Peleus,

the rage that brought myriad griefs down upon the Achaeans

and hurled many strong warriors’ souls to the house of Hades.

Sing the rage that left their bodies exposed, a feast

for all of the scavenger dogs and birds.

And sing how the will of Zeus was being fulfilled,

from its origin, the moment that it began, the conflict between

the son of Atreus, lord over men, and goddess-born Achilles.

The first three words of the Iliad are μῆνιν – rage or anger, ἄειδε – sing (in the imperative form, a.k.a. the bossy form, which we show in English with tone of voice or maybe an exclamation point: sing!), and θεὰ – goddess. The goddess is not named.

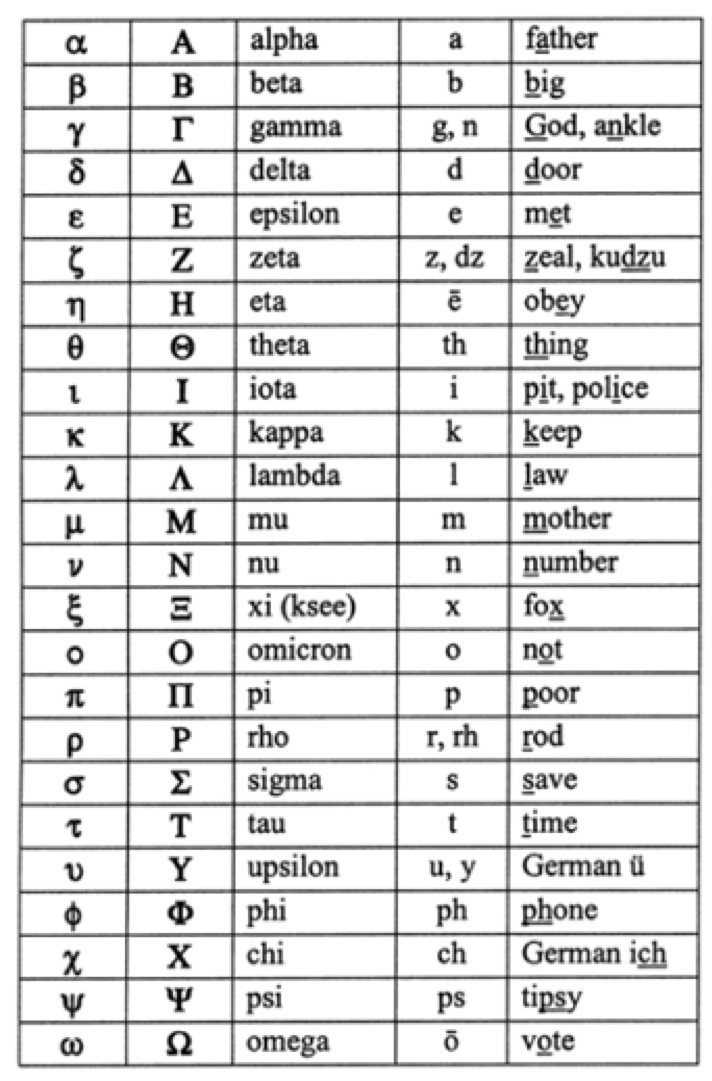

We will return to the central theme of μῆνις (rage) in the next couple of weeks. For today, please focus on the opening evocation of a goddess: ἄειδε θεὰ “sing goddess.” We know the divinity called upon to sing in line one is gendered female because in the Greek language all nouns (and adjectives) are gendered masculine, feminine, or neuter — and θεός, a male god, would show an omicron and sigma at the end of the word. (See the Greek Alphabet included below, for your reference).

Please discuss:

Scholars have long agreed that the unnamed θεὰ called upon here to sing is a Muse, one of nine daughters of Zeus and Mnemosune (the goddess of memory). Gregory Nagy suggests that she is Calliope, the Muse of poetic inspiration. Who you think this goddess might be?

Is the goddess – perhaps the Muse Calliope – the true “author” of the poem?

3. (10 minutes) What happens when you consider these three suggestions together?

(1) the Iliad represents the cultural values and ideas of a whole community; it was derived from a shared oral tradition rather than a single author;

(2) within the poem, a goddess, possibly/probably a Muse is credited with its authorship;

Please discuss whether a critical race feminist approach to the poem invites us to elevate or emphasize the Muse-as-author and, if so, what this means for how we understand the poem.

Pause for a 15-minute break now.

4. (15 minutes) More Muses

In book two, the Muses are invoked by name – twice. Following the Alexander translation, at 2.484 we see them called out in the plural:

Tell me now, Muses, who have your homes on Olympus –

for you are goddesses, and ever-present, and know all things,

and we hear only rumor, nor do we know anything—

who were the leaders and captains of the Danaans.

As for the multitude, I could not describe nor tell their names,

not if I had ten tongues and ten mouths,

or a voice that never tired, and the spirit in me were as bronze;

not unless the Muses of Olympus, daughters of Zeus who wields the aegis,

should remember all who came beneath the walls of Ilion.

Yet the leaders of ships I will recite, and the ships themselves, from

start to finish.

And then, at the conclusion of the naming of the leaders of people and places, the Muse is evoked in the singular:

Such then were the commanders of the Danaans. (760)

Tell me, Muse, who of these was very best,

Of the men and horses, who followed Atreus’ sons?

οὗτοι ἄρ᾽ ἡγεμόνες Δαναῶν καὶ κοίρανοι ἦσαν:

τίς τὰρ τῶν ὄχ᾽ ἄριστος ἔην σύ μοι ἔννεπε Μοῦσα

αὐτῶν ἠδ᾽ ἵππων, οἳ ἅμ᾽ Ἀτρεΐδῃσιν ἕποντο.

5. (15 minutes). Introducing the Goddesses

These Muses play a unique role in the poem, but they are perhaps not the most memorable goddesses to appear. The compelling goddesses of the Olympian pantheon are one of the most enduring residues of the ancient Greek world. The Iliad is the oldest extant written source that we have for what has come to be known as Greek mythology. Please work together for the final 15 minutes of today’s workshop to list the goddesses that you’ve met so far and describe them. What do they do? What do they say? How are they treated? You may also begin to list male gods – and compare them to the goddesses. Please make notes of your observations. This will be the preliminary work for our ongoing exploration of human and divine characters — female and male — in the Iliad over the next few weeks.

Greek alphabet, again, for your reference:

*note that ς also appears for sigma at the end of a word.