20 Briseis’ Dream

Jayda Delatorre

The Iliad, in its portrayal of women, has left much to be imagined about the trauma and tragedy of female-identifying characters. As the Iliad has been used as inspiration for centuries, the art that follows it has followed its narrative of glorifying the men who star in the work and leaving the women in the dust. Briseis is arguably one of the most important characters in the book and a catalyst for Achilles’ whole development, yet she is mentioned so rarely you forget she is even there. Never, at any point, are we given insight into her character, the trauma she feels, or the challenges she faces in being tossed between men as a “prize.” Similarly, the most prominent works of art featuring her follow this pattern; never is she central. She is visually maneuvered by men or trapped in the foregrounds.

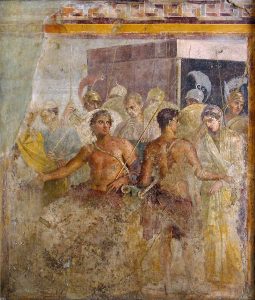

The Taking of Briseis

Roman fresco from Pompeii, c. first century ad

In this image, Briseis is being grabbed by the wrist by Achilles and physically handed over to other men. Even during transition between ownership, she is not being given the autonomy to walk herself over to Agamemnon’s men. She is covered very conservatively in white, which probably signifies her holy, pure reputation as a prize for these men. She also has very light skin, shades whiter than the men standing next to her. The look on her face is a look of surprise and/or fear. It is clear she is not happy by what is happening to her.

Briseis returned to Achilles by Nestor

1630 – 1635. Oil on panel. Rubens, Peter Paul.

Here, dressed again in white, she is being exchanged between men. Her skin is also whiter than most, and now she has light blonde hair as well. What is alarming to me is how young she looks here, especially in contrast with Nestor who is quite literally grabbing her by the waist and ushering her forward. Although she doesn’t look as scared as before, she also doesn’t look particularly happy either. I also thought the descriptions of the peace symbols were important to include. They are right- the image is supposed to be a peaceful, end of conflict- but for who? Achilles gets his “prize” back, but does Briseis get any peace? The only person who she seemed to care about, Patroclus, is now dead. How does this moment give Briseis any peace?

Eurybates and Talthybios Lead Briseis to Agamemnon

1757- Fresco, 300 x 280 cm. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

Here, she is AGAIN white and wearing white, and she looks uncomfortable as she is surrounded by men. Again, we have men physically sandwiching her and coercing her into going to Agamemnon. Visually, she is trapped between these men, and she seems to be portrayed with fragility as well, almost as if she can’t even walk on her own.

Achilles Receiving the Envoys of Agamemnon

1801. Oil on canvas. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres.

Here, she is seen for the first time not covered in white and not crying, but really, we barely see her. The only time we see Briseis out of the physical embrace of men and their gaze is when she is a background figure.

Briséis entraînée de la tente d’Achille

Circa 1761. oil on canvas. Jean-Baptiste-Henri Deshays

Here we are, back on track- wearing white, looking pretty, crying, and boxed in by men. This time, we have the added surprise of a nip-slip! (Hey! Blue Guard! Her eyes are up there!) This time, her hair seems especially elaborate and she is adorned with pearls and a more ornate looking dress. I also think it is interesting the way that the golden spear rests right above her head followed by the men, almost signifying how the men are above her power-wise, and war is above them all.

COUNTER NARRATIVE ART:

For my project, and especially after seeing all the existing art of Briseis, I wanted to create something of her where she is central, where men aren’t touching her, where she and other female-identifying characters will get a bit of justice for the violence carried against them.

In my painting, I painted Briseis standing between Achilles and Agamemnon, having just stabbed Agamemnon with a spear and coming for Achilles next. I thought it would be powerful to use the weapon that they are so well known for be the one that causes their death. The pillars on the side are also supposed to mirror them, with one (Agamemnon) cracking and breaking apart and the other (Achilles) about to follow. In my original design, I had wanted to depict some of the goddesses as carvings in the pillars. I really liked the idea in the Paul Rubens painting of using statues as a way to give insight of what the gods think or are doing. Unfortunately, my art skills disagreed with this. I wanted to have Hera looking smug and maybe Aphrodite and Athena together, all three of them “inspiring” Briseis and breaking away from Zeus’ will. The hands below are sort of what I thought Gaia would be doing, or really just the natural earth- holding Briseis up in her reclamation while pointing sharp spears towards the men who swapped her back and forth. This is also why I wanted Briseis in green, rather then something like white or blue. I don’t want her to be heavenly and holy like she is in the other paintings, I want her to be real and to be supported by nature. None of them have faces because I sort of felt wrong trying to shape a face for any of these characters, and also because painting faces is hard. The process of painting this was very strenuous, but fun! I honestly think the sky was the hardest part, but the hands underneath did take forever. It feels nice to make something completely new from my brain, rather than copying some art I found online or following a painting tutorial.