34 The Servant’s Family History

Jayda Delatorre; efinster8959; and kksa2018

Our group decided to create family trees for some of the unnamed servant girls who Odysseus hangs upon returning to his household. In class, we discussed how Odysseus couldn’t openly kill all of the suitors as they were men, and being men, it was less socially acceptable to slaughter them. The suitors all had enough class and power that if they died, they would be missed and there would be negative repercussions to Odysseus. Odysseus, however, openly hangs his slave girls because he knows there will be no consequences to his actions. Since servant women were seen more as commodities than as actual people with actual importance to others, Odysseus is comfortable with slaughtering them. We wanted to challenge the idea that these women were just expendables by giving them a history. Each of us tried to identify different stories of the girls which were probably likely- with some being brought from other villages via conquests, some on the verge of escape, and some missing their family desperately. By creating a family history, we are making a version of the story where the girls are not just expendable background characters, where they will be missed deeply, and where Odysseus has consequences for killing mercilessly.

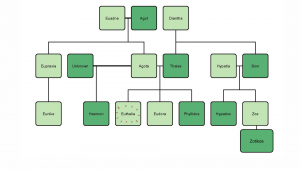

by Jayda

Here is the story of Euthalia, a young servant girl who had plans to run away. Euthalia had a sizeable family, who weren’t exactly well off, but who weren’t desperately poor either. Her family had been traveling through Ithaca when Euthalia had gotten lost and separated from her parents. She was unable to locate them, and wandered around Ithaca until being found by a laborer of Odysseus, who could appreciate another orphan to use for labor. Euthalia’s family looked for her desperately, until they saw her being taken to work for Odysseus. The man who was taking Euthalia said that she belonged to Odysseus, and if they wanted their daughter returned, they would need to take it up with him. However, upon going to Odysseus’s home, they were told that Odysseus was away and had been away fighting for several years- and that there was no word of his return. The family desperately tried to reclaim their daughter, but were turned away and told to wait for Odysseus’ return. Euthalia, who was very young at the time, never stopped wanting to leave with her parents. Although the medial labor of the household wasn’t too unbearable, Euthalia hated her life there. She was constantly approached by older men, forced to work long days, and was never rewarded for it. She had planned many attempts to escape from the home, but each time fate or her fear wouldn’t allow it. Her family had promised her that when Odysseus returned, they would pay any cost to have her safely returned. When the family eventually discovers the fortune of their daughter, they vow to have their revenge and honor her name.

by Kate Finster

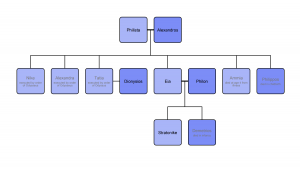

I decided to write from the perspective of a servant girl whose family has been enslaved for generations by the ruling family of Ithaca. How would she react to her execution when she has always been viewed as disposable?

Nike’s story is simple. Her parents were slaves. Their parents were slaves. And so on, until her ancestor, one of the first herders on Ithaca, was born. When Nike was born, her mother Philista groaned, “Another daughter,” and handed Nike to her eldest sister Eia while younger sisters Alexandra and Tatia scratched in the dirt outside. It wasn’t that Philista wanted a boy, though—he would have been killed or conscripted into whatever ragtag group of soldiers were needed to fight some war far from home. Plus, her only son Philippos died during childbirth, almost claiming Philista’s life alongside his. Nike joined her sisters in the small herding town in the hills above Odysseus’s home, where they would inevitably be sent once they were old enough to work as servants. After all, their family belonged to the son of Laertes, the long-absent King of Ithaca, Odysseus.

Nike joined her older sisters as a serving girl at 12, working for the royal family of Ithaca. She served them honey and cheese, offered hunks of freshly slaughtered lamb, and poured wine from amphorae. She stripped beds, beat rugs, and swept halls, working always alongside her sisters, cousins, and the other village girls. Nike never thought of leaving the island. Her entire family had toiled in the fields and within the home for centuries. Servitude was her birthright, and there was never a moment where she doubted her place within Ithaca’s insular social structure. Visitors would come and go, and servants would arrive from other islands to work, but no one who wasn’t a hero or a man ever departed. No one of even slightly nobler birth, not even the lesser families or those who had squandered their land, acknowledged Nike beyond beckoning her to refill their cup.

When the massacre of suitors happened, Nike was outside, washing linens in a nearby stream. Birds chirped and she sang with her sister Alexandra as they beat robes on a sunny rock. The clang of metal reached their ears once or twice, but they were blissfully unaware of the bloodshed occurring as Odysseus reclaimed his home and exacted his revenge. When the soldier came to them, sword outstretched, Nike, Alexandra, and the other servant women quickly exclaimed their innocence and believed wholeheartedly a mistake had been made. As he grabbed her arm and shoved her forward, Nike remained in a state of numb shock, confused why he suddenly deemed her a threat—or even worth attention at all. She had quietly served the family, just like her parents, since she was a child. As Nike huddled with her sisters and the other girls, waiting for her fate, she felt an overwhelming, jarring, sense of confusion. Why was she suddenly a target of violence, when her entire childhood had been mundane and filled with selfless service? As Alexandra cried in her arms, Nike considered: how could she expect any end different from this one? Her biggest mistake was assuming she was not this disposable in the first place.

by Camille Molas

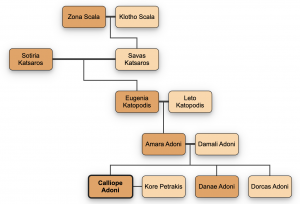

The story of Calliope Adoni.

Calliope Adoni is a slave servant that fell under the violence of suitors and Odysseus. However, Calliope’s early life was not as a slave. Calliope was the daughter of a ruling family in a nearby land. Her mother, Amara was the leader of the small land, just as her mother was before her and her grandmother. Their family line traces back to strong matriarchal ties. Because of this, Calliope was destined to assume her mother’s role. Calliope was the oldest child of Amara and Damali with a brother and sister named Dorcas and Danae. The three often get into trouble with each other as they explored the wilderness in their lands. Calliope was a strong girl, frequently showing her skill in battle and games. Athena had taken a liking to Calliope since she reminded her of herself. Calliope was 18 years old and was engaged to Kore, whom she had known since she was a child. Calliope lived her life in comfort surrounded by family and love. Tragically, a fight broke out against their land and another land days before her wedding. During this fight, the men in their family fought to protect their people. Kore, one of the warriors at the age of 19 fought and was slained. It wasn’t too long as the other lands massacred the adult men in their land. Thankfully, Calliope’s siblings and mother were able to survive. However, Calliope was taken as a prisoner of war and left with the men that ransacked her city. Calliope spent months on boats and became a slave to various people. Until one day landing in Ithica and was acquired by Odysseus’s household. At this point Calliope is now 19 years old.

While Calliope spent her time as a slave on boats, her siblings under the order of their mother search endlessly for her. They spent months traveling to various nearby lands looking for Calliope but to no avail could not find her. To this day, her family weeps for their loss and hopes to find Calliope. Despite Odysseus, quickly believing that slaves are not humans with history and family, let be known that this is not true. Calliope is only one example of a sweet, innocent girl that has a family and a history.

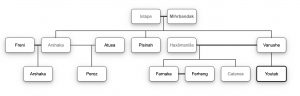

The story of Youtab (tw: ass*ult)

By: Kate Shimamoto

Youtab, bright from the light that kisses the soil of Persia, you are my sun child.

In the Persian invasion against the Greeks, Youtab, her mother, and one of her brothers were taken captive. Whispers and speculation had circulated of the Greek army drawing closer. Finally, one night she awoke to her mother screaming and barbaric-looking men storming in and ripping her from her bed. Her father and other brother were defending the walls outside; she could only assume they too had died among the thousands of bodies. Youtab, the sun child, removed from the beautiful fields of her homeland and the comfort of her family, was sold to the King of Ithaca. She was no longer the sun child but a slave, her brightness dimmed with fear, her former self forgotten in the effort to survive. She dreamed of bribery; her family had lots of money back at home, she wondered where it must have gone. Could she be found? Her existence was a complete erasure of any recognizable part of herself, as she became what she was told, what was demanded of her and slapped and whipped out of her. A slave girl. One of 15. A slave to the awful suitors, who smelled like rancid pork belly and smoke, who touched her and smelled her back and spat on her, who took their pent up aggression and frustration out on her and the others. However, when the suitors were finally slain, the attack was concealed as the men came from status and wealth. To kill the sons of Greek families, of highest status and political leverage, future inheritors vowing for the throne of Ithaca, would cause a great outrage if not hidden well. However, what would match the anger of a family whose daughter was stripped away, harassed, and then killed with no justification or justice? Her body was not hidden buried deep within the earth, but rather tossed away, unchallenging in its loneliness. Odysseus was not scared of killing the slave girls. They were seen as expendable, sacrifices, unthreatening; all descriptors of things. Her death was not considered as a death of a sun child, but a death of the other.