44 Imagining Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis

efinster8959

by Kate Finster

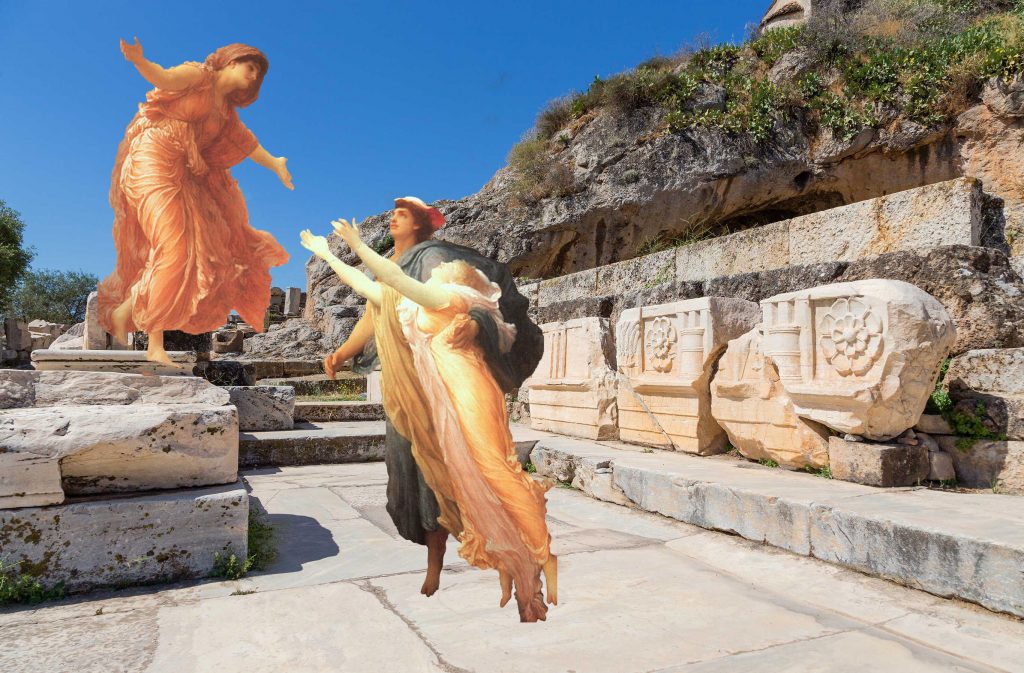

For my Homeric Hymn to Demeter pressbook entry, I wanted to focus on a visual reflection on the Hymn and its significance to the Eleusinian mysteries. I was fascinated by the rituals of the cult of Demeter (alongside other cults of antiquity) and how they tied their pilgrimage and rites to a sacred location. Why was the Eleusinian site such a place of power? Did they base the location of the ritual simply on where the myth told them to go, or was there a special, mystical magnetism to the ritual site? Demeter is a goddess grounded in Earth and physicality, meaning the location of her cult likely had great significance—greater than other gods who controlled the ocean or skies, for instance. These questions came up for me as I read both the Hymn and the readings on the rites of the Eleusinian mysteries.

In addition, the strong visual tradition of depicting the Demeter/ Persephone myth throughout art history to symbolize fertility, coming of age, female power (and lack thereof) also stood out to me as a representation of the legend’s enduring resonance throughout Western history. Therefore, I decided to juxtapose the physical space where the Eleusinian mysteries took place with the visual depictions of Demeter and Persephone that recur throughout the Western art historical canon. We discussed in class how Persephone was often depicted in later retellings and artistic renderings as the “queen of the underworld,” centering her bridal status and tie to Hades instead of her status as a child and victim of abduction. I found that to be true in the images that came up — Persephone’s youth and beauty were the subject of the artworks, not her traumatic experience, or even Demeter’s grief. Emotional responses were not present unless the painting showed Demeter and Persephone being reunited.

When selecting the paintings, I chose to focus on European artists ranging from the Baroque to Pre-Raphaelite periods due to the popular resurgence of classical myths in art, as societal movements began to focus on ancient culture and philosophy as inspiration for the industrial, religious, political, economic and societal upheaval unfolding in Europe. In addition, during this period, the portrayals of gods and goddesses were increasingly realistic, making it easier to transpose their figures onto a photograph of Eleusis and have it make sense aesthetically. Paintings of Persephone on ancient pottery, for instance, were more stylistic and two-dimensional, which would have looked less realistic on a modern photograph (though ancient paintings and sculpture are, of course, more accurate to how ancient Greek society viewed Persephone and Demeter).

By placing the figures of Demeter and Persephone in the space where the mysteries took place, it gives the aura of legitimacy and possibility to the ruins. I imagined what it could look like if the events of the Homeric Hymn actually took place at the site of Eleusis; or what the initiates of the Eleusinian mysteries saw during their final rituals.

I wanted to experiment with digital art and collage, using my more creative and visual side instead of writing a counter-narrative or analyzing a text like my previous pressbook entries. I used Photoshop, but have never taken digital art and am a huge novice at using the program, so please forgive any wonky inconsistencies you see 🙂