Designing the Course Curriculum

A future microbiome-centric agriculture: changing the corpus

“Soil is a living breathing system. Sometimes we have to feed it a little for it to feed us. It is a relationship.”

Dan DeSutter, Indiana farmer, Living Soil Documentary

As the direct stewards of hordes of diverse and strange microbes, farmers are uniquely positioned to usher in a future microbiome assisted agriculture. To understand farmer relationship to microbial life today, I will evoke the corpus-praxis-kosmos complex, a framework borrowed from ethnoecology. The corpus-praxis-kosmos complex is “the process by which people incorporate observations of biological interactions and ecological processes into natural resource management and their worldview” (1). In our context, the corpus consists of the body of knowledge held by farmers relating to microbes; praxis is their management decisions impacting microbes; kosmos encompasses farmer beliefs, myths, or worldviews concerning microbes.

If the future of agriculture is to be more microbially-centric, then farmer corpus-praxis-kosmos concerning microbes must radically shift. Farmer microbial corpus is foundational. Shifts in corpus change praxis and kosmos. Knowledge intensive microbially cognizant management practices (praxis) require a depth of biological understanding ranging from ecology, to microbiology, to genetics. Similarly, worldviews (kosmos) that are microbially inclusive and inquisitive as opposed to microbiophobic necessitate microbial literacy.

If our goal is to empower farmers to become active stewards of microbial biodiversity, researchers must first make the invisible world of microbes visible. As stewards of food systems, farmers need to hone their microbial literacy with the assistance of microbiologist, ecologists, and other diverse scientific specialists. Especially within the context of accelerating climate change and severe erosion of biodiversity, farmers must be constantly learning core ecological principles to inform the management of complex agroecosystems. Greater understanding of ecological processes enhance ability to adapt to changing environments.

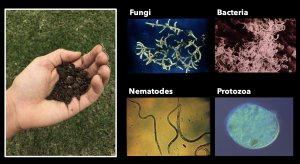

Image 1. The Hidden World of Microbes

A transition to a microbially aware agriculture requires the creation of a new knowledge base (corpus). There is urgent need for platforms that support farmer microbial knowledge integration (not standardization). These new knowledge bases should be holistic and diverse, incorporating formal and informal knowledge on global and regional scales. Farmers must be considered “knowledge co-generators” (2) in these new systems, not just passive recipients of knowledge held by researchers. Knowledge co-creation is a critical prerequisite for system transformation (3). Novel social infrastructure encouraging free flowing knowledge exchange is needed to support the transition to a regenerative and microbe-centric agriculture.

Filling a gap in knowlege infrastructure

The goal of this project is to contribute to this necessary knowledge infrastructure. I have designed a science-based curriculum aimed at farmers interested in enhancing their microbial literacy. The overarching aim is to render microbes visible to farmers and facilitate a more balanced narrative surrounding microbial functioning in agroecosystems. I will counter farmer microbiophobia by focusing especially on the myriad ways microbes could assist a regenerative agricultural paradigm. Although the curriculum is designed specifically for farmers seeking to enhance microbial knowledge, this material can also help extension agents, curious citizen scientists, and other non-experts interested in enhancing their microbial literacy.

This course fills a gap in current microbial knowledge infrastructure. The majority of courses exploring the microbial foundation of farming are behind paywalls. Dr. Elaine’s ™ Soil Food Web School is a prime example. These online offerings explore soil food web dynamics with emphasis on microbes, but the normal cost of the four-course package is $5,000. Another online resource behind a paywall is MYCOLOGOS, Peter McCoy’s mycology education courses. His course of on fungal ecology is priced at $697. Agroecologist Nicole Master’s online Soil Health Foundation course is more affordable costing $333, but still behind a paywall.

There are many free resources available on the internet discussing diverse topics intersecting microbial ecology and agriculture (YouTube videos, podcasts, blog posts, etc.). However, these sources of information are disjointed and do not paint a complete or integrated picture for farmers interested in enhancing microbial literacy. Furthermore, combing through the enormous quantity of free resources available and assembling knowledge piecemeal is a significant expenditure of time that many farmers, even the most motivated farmers, may not be able to afford.

Then there are free extension agent resources. On the one end of the spectrum, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) Soil Health website provides a holistic depiction of the living soil, emphasizing the biology and dynamic properties. However, the user interface is outdated, and this biological framing of soil is the exception, not the rule. Searching diverse extension sources reveals that many of these resources are of limited utility to farmers interested in holistic learning about soil microbes. For an illustrative and concrete example, searching “bacteria” on the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources’ site exclusively yielded results focused on management practices to control or eradicate bacterial diseases (such as citrus greening, almond leaf scorch, fire blight, or olive knot). This information, while helpful in certain contexts, is astoundingly one-sided and contributes to the false notion that microbes are exclusively (or at least mostly) bad. Searching “fungi” on the same cite yields similar results—they are wholly focused on how to control or eradicate “nuisance” fungi.

This curriculum will begin to fill this existing gap in knowledge infrastructure by providing free, open access, balanced, and integrative knowledge about microbes and agriculture. The curriculum will provide open access digital resources. All learning materials will be licensed as Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC). It is my hope that by creating open access content, others can share and adapt the material, perhaps building upon the material to add further to the growing corpus that we must build piecemeal to enhance farmer ecological literacy.

Image 2. Creative Commons License

Designing a curriculum exploring the hidden world of microbes

The curriculum is designed around four sequential units. Each unit focuses on answering a motivating question. Within each unit, there are modules addressing parts of the motivating question.

Unit 1 asks “What microbes are living in my soil?”

This unit sets the scene and introduces the key microbial players in the living soil. Unit one introduces foundational microbiological terminology such the difference between microbes and microbiomes and terminology that describes the scene of plant and microbial interactions such as rhizosphere.

Image 3. Microbes in the Living Soil

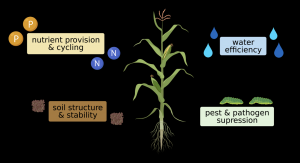

Unit 2 asks “How do microbes benefit the farm?”

This unit explores how microbes act as plant allies by provisioning and cycling nutrients, suppressing pests and pathogens, and improving water use efficiency and soil structure. Unit two dives into diverse farmer relevant topics such co-evolution, mycorrhizal symbiosis, nitrogen fixing bacteria, the rhizosphere effect, disease suppressive soils, among others.

Image 4. Microbes are Plant Allies

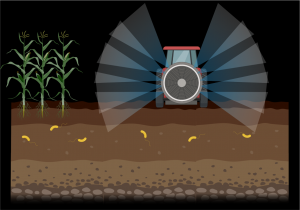

Unit 3 asks “How do current agricultural practices harm microbes?”

This unit explores the origins of farmer microbiophobia. Unit three also uncovers ways in which industrial agriculture disrupts soil microbiomes through heavy reliance on pesticide and fertilizer input, frequent tillage, and monoculture.

Image 5. Industrial Agriculture Simplifies Soil Microbiomes

Unit 4 asks “How can we build a microbially-assisted agriculture?”

This unit explores on-farm practices that support diverse and disease suppressive microbial communities. This unit examines how cover cropping, no-till, perennial agriculture, polyculture, and animal integration shift belowground microbial populations. This unit also explores how to develop on-farm monitoring of microbes. Farm monitoring is necessary to inform best management and track progress as farmers transition to more microbially-centric agricultural practices. This unit also briefly surveys successful examples of farmer learning networks such as the Farmer Field Schools developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (4) or farmer microscope clubs developed in Western Australia (1).

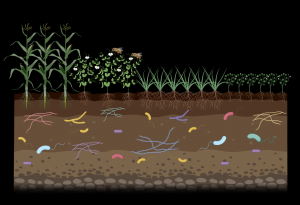

Image 6. Regenerative Agriculture Supports Diverse Microbiomes

Resources

- Pauli N., Abbott L.K., Negrete-Yankelevich S., Andres P., Farmers’ knowledge and use of soil fauna in agriculture: A worldwide review. Ecology and Society 21 (2016).

- Šūmane, et al., Local and farmers’ knowledge matters! How integrating informal and formal knowledge enhances sustainable and resilient agriculture. Journal of Rural Studies 59, 232–241 (2018).

- Pretty, et al., Global assessment of agricultural system redesign for sustainable intensification. Nature Sustainability 1, 441–446 (2018).

- MacMillan T, Benton TG, Agriculture: Engage farmers in research. Nature 509, 25–7 (2014).

Image Citations

Image 1. The Hidden World of Microbes

Alex Lintner. Illustration. BioRender.com. May 2021. Attribution CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image 2. Creative Commons License

Graphic. Public Domain.

Image 3. Microbes in the Living Soil

Alex Lintner. Photograph. May 2021. Attribution CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image 4. Microbes are Plant Allies

Alex Lintner. Illustration. BioRender.com. May 2021. Attribution CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image 5. Industrial Agriculture Simplifies Soil Microbiomes

Alex Lintner. Illustration. BioRender.com. May 2021. Attribution CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image 6. Regenerative Agriculture Supports Diverse Microbiomes

Alex Lintner. Illustration. BioRender.com. May 2021. Attribution CC BY-NC 2.0.