Closing Remarks

“When we put everything we’ve got into the service of a vision, the world takes notice and reality shifts.”

Charles Eisenstein (88)

An immense challenge of the 21st century is to determine how we can continue the experiment of agriculture without degrading the integrity of Earth. One overlooked harm of industrial agriculture is the disruption of soil microbiomes. Microbes, the “unseen majority,” constitute the foundational life support of the Earth—all macroscopic organisms live in dynamic relationship to microbes. However, there is a pervasive societal microbiophobia that perceive microbes as bad actors. This microbiophobia extends to farmers and impacts their land management decisions. Standardized agriculture focuses on killing microbes that act pathogenically as opposed to supporting beneficial microbes—this approach produces soil dysbiosis, creating further opportunity for soil pathogens to emerge.

Agrilogistics’ erasure of the centrality of microbes is shortsighted and unsustainable. Soil biology is of central importance to agroecosystems and microbes confer diverse benefits to agroecosystems. In an ecologically aligned agriculture, biodiversity, especially microbial biodiversity, can replace agrichemical input. If we are to transition out of the environmentally destructive agrilogistics paradigm and into an agriculture that is microbially cognizant and ecological resilient, we urgently need to develop systems that enhance farmer microbial literacy. Unlike a technology intensive agrilogistics, an ecologically resilient and regenerative agriculture must be knowledge intensive since management strategies are tailored to local ecologies.

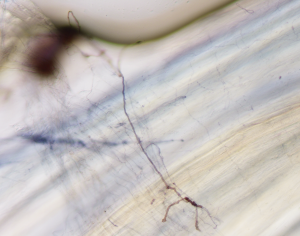

Image 1. Mycorrhizal Hyphae in a Plant Root

To enhance literacy, scientists and educators must render the invisible world of microbes visible to farmers. Once taught to holistically consider and observe microbial populations, farmer land management practices shift. As stewards of active herds of microbes, farmer microbial education has enormous transformative potential. Especially within the context of accelerating climate change and severe erosion of biodiversity, farmers must be constantly learning core ecological principles to inform the management of agroecosystems in changing environments. By equipping farmers with knowledge of microbes, farmers will have increased capacity to work with biological tools instead of relying solely on chemical or mechanical tools. Increasing microbial literacy encourages farmer innovation and place-based solutions. This literacy enables farmers to work alongside microbes as allies.

However, the invisibility, complexity, and general opaqueness of microbial life makes learning about the “black box of soil” difficult. To address this challenge, my project-based biology senior thesis endeavors to develop a biology-based curriculum for farmers to increase microbial literacy. A transition to a microbially centric agriculture necessitates the development of a new corpus. My senior thesis project aspires to contribute to this new, necessary, and expanding corpus. It is critical that farmers recognize their unique role as stewards of not only plants and animals but also as shepherds of an unfathomably complex, necessary, and wondrous herd of microbes.

Image Citations

Image 1. Mycorrhizal Hyphae in a Plant Root

Alex Lintner. Microscope Photograph. April 2019. Attribution CC BY-NC 2.0.