4 Cuerpo-Territorio and the Capital-Life Conflict: Creating the telaraña in Ecuador

mjdb2020

Cuerpo-Territorio and the Capital-Life Conflict: Creating the telaraña in Ecuador

By: María Juanita Durán G.

A figure of map Ecuador with people

Credit: depositphotos

The Voices of the Web: Introduction

Pensamos el cuerpo como nuestro primer territorio y al territorio lo reconocemos en nuestros cuerpos: cuando se violentan los lugares que habitamos se afectan nuestros cuerpos, cuando se afectan nuestros cuerpos se violentan los lugares que habitamos (Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 2017).[1]

We think of the body as our first territory and we recognize the territory in our bodies: when the places we inhabit are violented, our bodies are affected, when our bodies are affected, the places we inhabit are violated (Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 2017; my own translation).[2]

Indigenous women in the Amazon have been at the forefront of the fight against climate change and the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, and today we are stepping up into new leadership roles, successfully forcing out extractive industries and companies from our sacred territories.

In response, women are being systematically targeted and persecuted by oil companies and the government. These attacks and threats continue unsolved and unpunished, and Indigenous women leaders continue to be unprotected. This is clear: extractivism and violence go hand in hand (Gualinga, n.d.).[3]

As heard from the voices of indigenous women, their bodies and territories are interwoven together. The well-being of one depends on the health of the other. However, global pressures of development and capital challenge the dependency between territory and life. On one hand, capital-life conflict prioritizes capital over human and territorial life, cuerpo-territorio is the indigenous feminist framework that counteracts capital as the center. Instead, indigenous framings seek to connect of bodies and territories, tethering an interconnected teleraña, or spider web, to dismantle capitalism’s foundation. I will examine the manifestations of the capital-life conflict in Ecuador, being reflected in the pattern of separating bodies and territories to exploit both simultaneously. Finally, employing the lens of cuerpo-territorio to connect the exploitation as interconnected.

I chose Ecuador because of its history of resource extraction, foreign capital investments, and feminist indigenous resistance, especially in the Amazon. The past and current narratives of the priority of capital and wealth building are a challenge to the life of marginalized people in the country. Yet, the cuerpo-territorio frameworks spoken by indigenous women in Ecuador, fight the dominant discourse of violence and extractivsm. Thus, they imagine a future of solidarity and collectivity of shared stories of bodies and territories together.

Weave: Theoretical frameworks

Decolonial and ecofeminist thought form the basis of the analysis of capital-life conflict and cuerpo-territorio because of how they contribute to the interrelated analysis of wealth, territory, and capitalism. In this section, I will be defining decolonial and ecofeminist thought’s formation of capital-life conflict and cuerpo-territorio.

My aim in this paper is to create a telaraña, or web of the connections between body and territory. To weave the telaraña, I employ a decolonial methodology, building on Mignolo and Walsh’s (2018) usage of “what some Andean Indigenous thinkers…refer to as vinculariadad…the awareness of the integral relation and interdependence amongst all living organisms with territory or land and the cosmos…Relationality/vincularidad seeks connections and correlations” (Mignolo and Walsh, 2018).[4] In this paper, I hope to show the relations, or vínculos between development, patriarchy, and capitalism that weave the web.

The web begins with the vínculos established by ecofeminism. Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies (2014) in Ecofeminism’s introduction frame how “in analyzing the causes which have led to the destructive tendencies that threaten life on earth we became aware—quite independently—of what we call the capitalist patriarchal world system” (Shiva and Mies, 2014).[5] Shiva and Mies are threading the relationships between the capitalist patriarchal world system and the “destructive tendencies that threaten life on earth.” The ecofeminist unifications between capitalism and exploitation form the foundation of capital-life conflict. In fact, in her article “Care? A Word Under Political Dispute” Amaia Pérez Orozco (2022) builds the connection between the intentions of the capitalist patriarchal world system to how the system creates the capital-life conflict. The system allows the

accumulation of private benefits by plundering the collective life and the planet life. But, with no life, there is no capitalism as well. Heteropatriarchy and neocolonialism guarantee the existence of employments and hidden economic spheres that keep life under siege… with no protest (Amaia Pérez-Orozco, 2022). [6]

The capitalist-patriarchal world system has built the thinking that capital, and the tools that maintain wealth, must be prioritized over life. The implications are the “plundering of collective life and plant life” that are kept “under siege…with no protest.”

The cuerpo-territorio framework sprouts from ecofeminism’s exposure of the effects of prioritizing capital over life. Cuerpo-territorio is the indigenous feminist theory that weaves environmental and feminized exploitation with the larger discourse of capitalist and patriarchal pressures. Sara Zaragocin and Martina Angela Carreta in “Cuerpo-Territorio: A Decolonial Feminist Geographical Method for the Study of Embodiment” (2021) explain cuerpo-territorio to be the “distinct, geographical, decolonial feminist method grounded in the ontological unity between bodies and territories” (Zaragocin and Carreta).[7] Ecofeminism traces the pattern that in the name of wealth, dispossession and exploitation of marginalized bodies and territories is common. Shiva and Mies help to see “the relationship of exploitative dominance between man and nature…and the exploitative and oppressive relationship between men and women that prevails in most patriarchal societies, even modern industrial ones…[as] closely connected” (Shiva and Mies, 2014).[8] The connection that Shiva and Mies see between domination of the environmental to gender oppression set the foundation for the reflections of indigenous women’s in cuerpo-territorio because the outlined impacts of capitalism and patriarchy of ecofeminism is then mapped on bodies, interpersonal relationships, and territories.

The telaraña is weaved through the theoretical frameworks, yet to see the vínculos at play, the web must unravel to depict how the capital life-conflict is on display in Ecuador and how cuerpo-territorio unites the relationships of body, territory, and capital.

Unravel: The Case-Revealing the Capital-Life Conflict

The capital-life conflict reveals itself when bodies and territories are divided for the purpose of producing wealth. Territories are the spaces for extracting materials for upholding wealth, and bodies are funneled to become tools for production—becoming collateral. The separation between people and their spaces is a strategy of capitalism; keeping both disconnected is beneficial for wealth building because exploiting two means of production means reaping the fruits individually. In Ecuador, this separation is revealed in how territories are violented for resources, and the bodies in those territories become disposable.

In Ecuadorian territories, the case of the capital-life conflict evidenced reveals a historical pattern of resource extractivism. The history of exploiting territories for obtaining resources stems from the socially constructed discourse of development. Arturo Escobar in “The Invention of Development” (1999) examines development as an imagined concept, constructed from dichotomized thinking. States were defined by wealth concepts; only rich Western nations knew and saw the measures of wealth. However, the measures were then assumed to be universalized, “thus poverty became an organizing concept and the object of a new problematization. That the essential trait of the third world was its poverty and that the solution was economic growth and development became self-evident, necessary, and universal truths” (Escobar, 1999).[9]

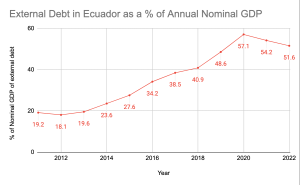

In the case of Latin America, Arturo Escobar’s arguments support that the socially constructed discourse enacts pressure on states to “develop” economically. The pressures only further the cycle of dependency on natural resources and foreign support (Riofrancos, 2021).[10] Extraction follows what Thea Riofrancos in Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador (2021) calls a “boom and bust cycles of global commodity markets.”[11] Riofrancos refers to the historical processes—or vicious cycles—of development in Ecuador. The periphery relies on extraction of materia prima to the Global North country to “develop” and repay debts, yet the debts will never be paid because they will continue to have their natural resources extracted by foreign powers. Ecuador’s international debt reached 51.598% of the country’s nominal GDP in 2022.[12] In addition, 25.2% of the country is in poverty and 8.2% in extreme poverty.[13] The statistics are meant to show the complicated development narrative in Ecuador: a country in peril because of the heightened pressures to enter the global market, while the country has an abundance of natural resources that in the eyes of development, can alleviate the pressure.

The eyes of development have been set on wood, minerals, and oil in Ecuador. Antonio José Paz Cardona in “For Ecuador, a litany of environmental challenges awaits in 2020” (2020), reports on the conditions of the wood extraction: “For its size, Ecuador has the highest annual deforestation rate of any country in the Western Hemisphere” (Paz Cardona, 2020).[14] Paz Cardona quotes Santiago Ron, a prominent biology professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador (PUCE), quantifies the exact rate as “more than 70,000 hectares [about 173,000 acres], which is a very high figure for a country the size of Ecuador” (Paz Cardona, 2020).[15] The natural world is being ransacked for its rich resources.

In addition, oil is a lucrative market that aims to springboard Ecuador out of debt. However, oil has torn through the country’s economy because of its dependency on foreign investment and pattern of environmental abuses. The energy minister of Ecuador, Fernando Santos told The New York Times (2023) that Ecuador is in “monstrous debt…But while [Santos] recognizes that oil played a role in creating the problem, he also sees oil as the solution. With more drilling and mining development, he said, ‘the country will be able to get out of debt’” (Einhorn and Andreoni, 2023).[16] The promise of wealth accumulation blinds government officials to ignore the ironies of development. However, when capital is prioritized, more problems unravel. In Ecuador, environmental degradation, more debt, and loss of quality of life for marginalized communities have been untangled.

Still, projects arise and expand to different industries. Open-pit mining in Ecuador exemplifies all the complications found within the capital-life conflict. The most contentious project is in

Zamora…the site of the ‘El Mirador’ open-pit copper mining project. This $1.4 billion project, developed by the Chinese firm EcuaCorriente, signaled Ecuador’s entry into large-scale mining and the launching of a new industry…The lands on which these projects would be taking place are predominantly Indigenous lands, and given the expected effects in terms of pollution, displacement of communities, and health concerns, Indigenous and environmental groups have fought to stop the project. (Bernal, 2021).[17]

Not only does open-pit mining explode mountains, but sacred territories and its people are dispossessed in the name of development. Ecuador has this foreign investment that can support a rising industry for capital accumulation, yet the bodies—their health and wellbeing—of indigenous people are put on a line. The capital accumulation through territory invasions fail to consider the casualties because the people on the margins are seen as disposable and factors for capital accumulation.

When bodies seek unison with their territory by protecting them, violence is launched. In the province of Azuay, indigenous water protector, Alba Bermeo Puín was murdered “by people involved in mining activities” (La Periodica, 2022; my translation).[18] Life becomes second to capital, and life is at risk for capital. Alba Bermeo Puín directly challenged capital accumulation by prioritizing her community’s access to water, and capitalist companies saw her as a liability to their wealth project. Her body and protection for territory were united, posing as a threat to the capital-prioritized state.

Unite: Analysis-Cuerpo-Territorio connecting bodies and territory

Indigenous feminists in Latin America have created vinculos, or related bodies and territories in their lens of cuerpo-territorio. In “Mapeando el cuerpo-territorio: Guía metodológica para mujeres que defienden sus territorios” or “Mapping cuerpo-territorrio: Methodological Guide for woman that defend their territories,” the collective writers of Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo (2017) explore how companies enacting control and violence show the necessity to adopt a cuerpo-territorio framing and unite of bodies and territory. They trace how “in extractivsm, nature, like women’s bodies, is considered a territory that has to be scarified to allow the reproduction of capital, which then can be exploited, violated, and extracted” (Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 2017; my own translation).[19] In capital-life conflict, the violence stemming from development is seen as part of exploiting separate means of productions to obtain capital. On the other hand, the cuerpo-territorio framing considers how development invites multinational companies to enact violence on women’s bodies and territories.

In Ecuador, the cuerpo-territorio unison is embodied in the crisis in the Yasuní National Forest, where for indigenous communities, their territories, and their bodies are being occupied. The conflict in Yasuní follows the story of ecological extraction and encroaching on indigenous lands and bodies. The New York Times reports in “Ecuador Tried to Curb Drilling and Protect the Amazon. The Opposite Happened” (2023) that the Yasuní is in the Amazon where “teams are drilling in one of the most environmentally important ecosystems on the planet, one that stores vast amounts of planet-warming carbon. They’re moving gradually closer to an off-limits zone meant to shield the Indigenous groups” (Einhorn and Andreoni, 2023).[20] The Tagaeri and Taromenane indigenous communities reside in voluntary isolation in the off-limit zone of the Yasuní, “their reserve and a related buffer zone are off-limits to drilling, but government officials have discussed shrinking the protective zone to reach more oil” (Einhorn and Andreoni, 2023).[21] The pressures to develop have reached the one of the world’s largest carbon sinks and the communities are at put at risk.

Las Mujeres Amazónicas protesting environmental exploitation.

Credit: Telesur and @Yasunidos

Las Mujeres Amazónicas, or Women of the Amazon are protesting the capitalist occupation by coupling the invasion of Yasuní to “another assault on Indigenous peoples from the Amazon” (Telesur, 2018).[22] The indigenous women collective are enacting their visions of cuerpo-territorio in their manifestations against Yasuní as they marry the violence on their ancestral territories to a direct assault on their bodies and communities. An image in the article “Ecuador: Indigenous Women Protest Move to Exploit Yasini” depicts several women protesting the oil expansion in Yasuní, and the poster behind them reads “MUJERES DEFENSORAS DE LA SELVA…NO más explotación no más genocido pueblo Sapara y Tagaeri y Tarromenane” (Telesur, 2018).[23] In English, the poster says “WOMEN DEFENDERS OF THE AMAZON…NO more exploitation, no more genocide of the Sapara y Tagaeri y Tarromenane pueblos.” Their protests mirror the decolonial vínculos between bodies and territories because they view the environmental exploitation as interrelated to the genocide of indigenous communities.

The Mujeres Amazónicas activists map the calamities of development onto the bodies of indigenous communities. Their voices call to attention what bodies hold the greatest burden in the name of capital: women and feminized bodies. The collective indigenous feminist writers of Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo (2017) support with a chorus of indigenous women’s voices that point to the bodies in the middle of the capital-life conflict and the repercussions:

When there is conflict in the territories, we feel pain that materializes directly in the body and specifically in the body of women: mines, oil wells, roads, contaminated water…etc. are damaged territories and that is where the violence takes place: feminicides, harassment, attacks on bodies that need to be cared for (Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo 2017, my own translation).[24]

Not only are the women indigenous activists drawing relationships between extractivism and the impacts on their communities, but they expand the relationship between body and territory to show how extractivism directly places the bodies of women in the middle of the conflict. Their livelihoods, like their territories, become the site for violence. There is a collective struggle among indigenous women to protect their lands and communities, and while they are the ones that need to be cared for, indigenous women are in the direct line of attack for capital-violence.

Power in Unity: Conclusion-Cuerpo-Territorio’s interrogation and imaginations

Besides a framework that supports their experiences, cuerpo-territorio becomes the place where indigenous women can seek collectivity for their shared struggle. “In the struggle and resistance” indigenous women build a unison of bodies and territories, they “find partners and our individual territories-bodies become collective” (Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 2017; my own translation).[25] The collectivity undermines the capital-life conflict because the fission of bodies across territories defies the collective narrative of exploitation, one that challenges the individualism of wealth-building that aims to keep bodies and territories separate.

The indigenous women of the Amazon in Ecuador build their collective story by showing the common threads of exploitation on indigenous women and their communities. In their mandate, The Amazonian Women Grassroots Defenders of the Rainforest Against the Extractive Economic Model, depict their collective narrative where women of indigenous nations

are threatened for the actions they have taken as human rights and environmental defenders, as in the case of Patricia Gualinga (leader from Sarayaku), Nema Grefa (President of the Sapara Nation of Ecuador), Alicia Cahuiya (Waorani leader), Gloria Ushigua (Sapara leader) (Gualinga, n.d.)[26]

All of the impacted women come from different indigenous nations, yet their struggles are linked. They are

Indigenous Amazonian women, who are defending the Amazon rainforest and our global climate by keeping the oil in the ground, are more exposed to experiencing multiple types of violence. Threats emerge from within and, even more so, from outside their territories. But for many Indigenous women there is no guarantee that their rights will be respected. We have knocked on the doors of the judicial system, we have appealed to the hearts of the government officials, but they keep trying to silence our voices. Because they know that our voices are powerful (Gualinga, n.d.). [27]

A chorus of voices connecting bodies and territories defy the capital-building mission as their voices counteract the power of capital in Ecuador. In their own words, “together we create alternative narratives of hope that allow exploration of coping strategies reinforcing the sense of…resilience.”

In conclusion, cuerpo-territorio resists the capital-life conflict in Ecuador. The work of indigenous women in Ecuador connects the deep relations between body and territory, seeking to unite them both when in a capitalist patriarchal system that aims to exploit them separately. The connections across spaces and bodies echo Amaia Pérez-Orozco’s claim that “we are interdependent and ecodependent” (Pérez-Orozco, 2022)[28]. Pérez-Orozco continues, “this deep awareness of the network of life allows us to denounce that these links are now corrupted” (Pérez-Orozco, 2022).[29] The awareness that women, their bodies, and territories are dependent unite to condemn how capitalism’s violence has corrupted the strong links between bodies and territories. The resistance and collectivity that comes from cuerpo-territorio re-nourishes the links that build indigenous women’s life in Ecuador—one that relies on interdependence of each other and of their territory.

They imagine the emergence of “un camino que lleve a rumbos diversos de reflexión y resonancias donde la articulación entre cuerpos y territorios sea estrategia para la defensa de los territorios que habitamos y de nuestras propias vidas” (Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 2017).[30] Or, the reflective path where the articulation of their bodies and territories is a strategy to defend their territory and of their lives. The indigenous women of Ecuador weave, unravel, and unite the telaraña of cuerpo-terrritorio as a space of reflection, relationships, and resilience. The collective re-prioritizes their life as their capital.

Footnotes:

[1] Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, “Mapeando el cuerpo-territorio. Guía metodológica para mujeres que defienden sus territorios.” Quito: Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo (2017): 7.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Nina Gualinga, “Indigenous women say this is clear: extractivism and violence go hand in hand. Mandate from Amazonian Women Grassroots Defenders of the Rainforest Against the Extractive Economic Model” in Rapid Shift blog. (n.d). http://www.rapidshift.net/indigenous-women-say-this-is-clear-extractivism-and-violence-go-hand-in-hand-mandate-from-amazonian-women-grassroots-defenders-of-the-rainforest-against-the-extractive-economic-model/

[4] Walter D. M Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh. “Introduction” On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press, (2018): 1-2.

[5] Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies. “Introduction” in Ecofeminism. Bloomsbury Publishing, (2014): 2.

[6] Amaia Pérez-Orzco, “Care? A Word Under Political Dispute,” Capire, April 14th, 2022. https://capiremov.org/en/analysis/care-a-word-under-political-dispute/

[7] Sofia Zaragocin, and Martina Angela Caretta. “Cuerpo-territorio: A decolonial feminist geographical method for the study of embodiment.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111, no. 5 (2021): 1503-1518.

[8] Shiva and Mies, 3.

[9] Arturo Escobar, “The invention of development.” Current History 98, no. 631 (1999): 382.

[10] Carmen Martínez Novo, Undoing multiculturalism: Resource extraction and indigenous rights in Ecuador. University of Pittsburgh Press, (2021): 274.

[11] Dr. Sibo Chen, “Book Review: Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post Extractivism in Ecuador by Thea Riofrancos,” 31st March 2021, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2021/03/31/book-review-resource-radicals-from-petro-nationalism-to-post-extractivism-in-ecuador-by-thea-riofrancos/

[12] “Ecuador External Debt: % of GDP,” CEIC, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/ecuador/external-debt–of-nominal-gdp

[13] Reuters Staff, “Ecuador unemployment fell to 3.2% in December last year-govt,” Reuters, 24 January 2023. https://www.reuters.com/article/ecuador-unemployment/ecuador-unemployment-fell-to-3-2-in-december-last-year-govt-idUSL1N3492JD

[14] Antonio José Paz Cardona, “For Ecuador, a litany of environmental challenges awaits in 2020,” Mongabay, 5 February 2020. https://news.mongabay.com/2020/02/for-ecuador-a-litany-of-environmental-challenges-awaits-in-2020/#:~:text=For%20Ecuador%2C%20a%20litany%20of%20environmental%20challenges%20awaits%20in%202020,-by%20Antonio%20Jos%C3%A9&text=For%20its%20size%2C%20Ecuador%20has,be%20national%20priorities%20in%202020.

[15] ibid

[16] Catrin Einhorn and Manuela Andreoni, “Ecuador Tried to Curb Drilling and Protect the Amazon. The Opposite Happened,” 14 January 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/14/climate/ecuador-drilling-oil-amazon.html

[17] Angélica María Bernal, “Ecuador’s dual populisms: Neocolonial extractivism, violence and indigenous resistance.” Thesis Eleven 164, no. 1 (2021): 9-36.

[18] La Periódica [@laperiodicanet], 1 November 2022, “#JusticiaParaAlba | La madrugada del 22 de octubre de 2022, Alba Bermeo Puín, defensora del Agua en Molleturo fue asesinada. Compartimos un resumen de la denuncia que publicó la Alianza de Organizaciones por los Derechos Humanos en Ecuador,” https://www.instagram.com/p/CkZ-unuO4_n/

[19] Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 49.

[20] Einhorn and Andreoni, 2023.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Telesur, “Ecuador: Indigenous Women Protest Move to Exploit Yasuni,” 14 November 2018. https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Ecuador-Indigenous-Women-Protest-Move-to-Exploit-Yasuni-20181114-0023.html

[23] Ibid.

[24] Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 13.

[25] Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 42.

[26] Gualinga, n.d.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Pérez-Orzco, 2022.

[29] Pérez-Orzco, 2022.

[30] Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 24.

Works Cited

Bernal, Angélica María. “Ecuador’s dual populisms: Neocolonial extractivism, violence and indigenous resistance.” Thesis Eleven 164, no. 1 (2021): 9-36.

Chen, Sibo. “Book Review: Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post Extractivism in Ecuador by Thea Riofrancos,” 31st March 2021, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2021/03/31/book-review-resource-radicals-from-petro-nationalism-to-post-extractivism-in-ecuador-by-thea-riofrancos/

Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo. “Mapeando el cuerpo-territorio. Guía metodológica para mujeres que defienden sus territorios.” Quito: Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo (2017): 1-53.

Ecuador External Debt: % of GDP.” CEIC, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/ecuador/external-debt–of-nominal-gdp

Einhorn, Catrin and Manuela Andreoni. “Ecuador Tried to Curb Drilling and Protect the Amazon. The Opposite Happened,” 14 January 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/14/climate/ecuador-drilling-oil-amazon.html

Gualinga, Nina. “Indigenous women say this is clear: extractivism and violence go hand in hand. Mandate from Amazonian Women Grassroots Defenders of the Rainforest Against the Extractive Economic Model” in Rapid Shift blog. (n.d).

La Periódica [@laperiodicanet]. 1 November 2022, “#JusticiaParaAlba | La madrugada del 22 de octubre de 2022, Alba Bermeo Puín, defensora del Agua en Molleturo fue asesinada. Compartimos un resumen de la denuncia que publicó la Alianza de Organizaciones por los Derechos Humanos en Ecuador,” https://www.instagram.com/p/CkZ-unuO4_n/

Martínez Novo, Carmen. Undoing multiculturalism: Resource extraction and indigenous rights in Ecuador. University of Pittsburgh Press, (2021): 274.

Mignolo, Walter D. M and Catherine E. Walsh. “Introduction” On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press, (2018): 1-2.

Pérez-Orzco, Amaia. “Care? A Word Under Political Dispute,” Capire, April 14th, 2022. https://capiremov.org/en/analysis/care-a-word-under-political-dispute/

Paz Cardona, Antonio José. “For Ecuador, a litany of environmental challenges awaits in 2020,” Mongabay, 5 February 2020. https://news.mongabay.com/2020/02/for-ecuador-a-litany-of-environmental-challenges-awaits-in-2020/#:~:text=For%20Ecuador%2C%20a%20litany%20of%20environmental%20challenges%20awaits%20in%202020,-by%20Antonio%20Jos%C3%A9&text=For%20its%20size%2C%20Ecuador%20has,be%20national%20priorities%20in%202020.

Reuters Staff. “Ecuador unemployment fell to 3.2% in December last year-govt,” Reuters, 24 January 2023. https://www.reuters.com/article/ecuador-unemployment/ecuador-unemployment-fell-to-3-2-in-december-last-year-govt-idUSL1N3492JD

Shiva, Vandana and Maria Mies. “Introduction” in Ecofeminism. Bloomsbury Publishing, (2014): 2.

Arturo Escobar, “The invention of development.” Current History 98, no. 631 (1999): 382.

Telesur, “Ecuador: Indigenous Women Protest Move to Exploit Yasuni,” 14 November 2018. https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Ecuador-Indigenous-Women-Protest-Move-to-Exploit-Yasuni-20181114-0023.html

Zaragocin, Sofia, and Martina Angela Caretta. “Cuerpo-territorio: A decolonial feminist geographical method for the study of embodiment.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111, no. 5 (2021): 1503-1518.