8 The Tanis Fossil Site and Paleontology on Private Land

Introduction

Tanis is a South Dakota fossil site that was discovered by commercial paleontologists in 2008. Tanis contains fossils preserved immediately following the Chicxulub asteroid (famous for causing a mass extinction) and is the first-known site of its kind. Initial discoveries of well-preserved fish prompted the recruitment of Ph.D. student Robert DePalma to the site. DePalma has worked at the site since, publishing initial findings in 2017 and then a full paper in 2019 (Smithsonian).

Along with some incredible findings, though, Tanis has also been the source of some controversy. The site is located on private property, and the landowner has given long-term paleontological rights to DePalma. While the information gathered at the site is critical to understanding the asteroid impact and the time period immediately after it, the fossils are owned by DePalma rather than any public institution. The ownership of fossils as well as some of DePalma’s research practices have faced criticism from fellow researchers (Macleans).

Who owns the right to scientific knowledge? When it comes to archaeology and artifacts preserved from earlier humans, there are often clear colonizer/colonized dynamics; in this case, the resource is valuable for informational rather than cultural significance. This draws into question who owns or who should control the flow of information from this dig site. Should institutions always have control over caring for dinosaur bones (as is more the case with fossils found on public land), or is private ownership just as effective? What systems and policies should be put in place to ensure that we can learn the most about the past?

Background knowledge

The scientific importance of the archaeological site:

Tanis is a one-of-a-kind site that demonstrates the immediate aftermath of the Chicxulub asteroid, which resulted in massive climate disruption and plant and animal extinctions. Uncovered artifacts were buried on a scale of 10 minutes to a few hours after the asteroid impact (PNAS).

Some of the especially notable artifacts include:

- Fish with ejecta spherules in their gills were found at the site. These spherules were produced in the immediate aftermath of the impact.

- Feathers that may have come from large dinosaurs

- The first example of a dinosaur probably killed by the actual asteroid impact: a thescelosaurus

- An intact egg with an embryo fossil

- Rare pterosaur fossils

- Fragments probably from the Chicxulub asteroid

These artifacts open a window into one of the most deadly days in earth’s history and make Tanis an incredibly rich and fascinating site.

More than just Robert DePalma and the paleontological community have become interested in Tanis. A recent documentary by the BBC showed the process of fossil discovery and brought life to the site with artistic recreations of what may have happened on that day.

(I definitely recommend watching the whole documentary, it’s very fun)

The controversy of the site:

But beyond exciting scientific findings and a fun documentary, Tanis and DePalma have faced controversy in several forms. When first introducing his findings to the world, DePalma published an article in the New Yorker. Other scientists were not happy that he first made bold scientific claims in a popular news article rather than in a scientific publication. A few days after the New Yorker article, DePalma and his collaborators did publish a paper. However, this paper did not include evidence for several claims mentioned in the article. While subsequent publications have backed up more of the article’s claims, this initial method of sharing the discovery was frowned upon by fellow scientists.

DePalma has complete control over verifying his own claims, as he owns the excavation rights to Tanis in a long-term lease with the rancher land owner. DePalma has also claimed ownership of the fossils after they are uncovered, rather than handing them over to institutions as is standard practice. This is legal on private land with the land owner’s agreement but frowned upon by others in the field. Some paleontologists believe that excavations should not be held on private land. While DePalma has invited prominent paleontologists to the site, he has full control over who has access. Other paleontologists say that this is effectively restricting access and preventing other researchers from verifying his claims. Jessica Theodor, the president of the society of vertebrate paleontology, criticized this behavior, saying, “If you donate your specimens to a repository, the whole point is that other people need to be able to verify your claims. If you’re trying to restrict access to them, that’s really problematic” (Macleans).

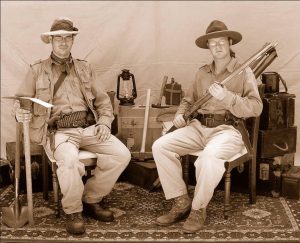

Robert DePalma has also received some criticism for his personal behavior beyond the Tanis site. Some other paleontologists see DePalma as enjoying the theatrics of paleontology more than the process of discovery and the furtherment of science. Others also criticize his old-fashioned view of paleontology, which can be exclusionary. Kirk Johnson, director of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, says that DePalma “is sort of doing cosplay,” as he dresses somewhat like Indiana Jones and gives talks with oil lamps for lighting (Macleans).

The value of this knowledge:

In an interview for The Dinosaur Channel on Youtube, Robert DePalma mentions that an appeal of this research is how it documents the immediate aftermath of an ecosystem adapting to a sudden change, on a time scale similar to what we are seeing with present climate change. “How does first biota respond to global-scale hazards?”, DePalma asks. Because paleontology looks at genuine case studies rather than models of predicted responses to environmental catastrophes, we can learn valuable information about our current climate change situation. Studying this past event could help us with predicting what may come our way in the near future.

More generally, paleontology is a way to understand the process of evolution and teaches us where we come from. It puts into perspective the different world we live in today and helps us piece together which environmental changes are paired with which effects. It also seems important to mention that for many, paleontology is just cool. Extinct species like dinosaurs inspire stories, artwork, films, and much more. Paleontology teaches us about an exciting past, with applications for the future.

However, in this case study, it seems that DePalma places value in much more than just the knowledge we can gain from Tanis site fossils. In the BBC documentary, DePalma is presented as a protagonist, and given nearly full credit for discoveries. Whether uncovering scales, preserving a dinosaur leg using liquid nitrogen, or explaining to the camera the daily stresses of a paleontology job, DePalma is the primary figure in this documentary. The same is true for the article that first published these findings. DePalma recruited novelist Douglas Preston to share his findings with the world. Both offer a much more literary description of DePalma’s work. He uncovers artifacts with the mission of discovering the full story of the site, and this is the primary conflict in the story both sources are telling. To DePalma, it seems that at least some of the value of this site is being the hero of the story of discovery.

So, paleontology is a fascinating field with relevant applications to today. But for some individuals, its value goes beyond just gaining knowledge about the world. While not as relevant to this case study, another value placed on paleontology is the monetary value of fossils. Commercial paleontologists collect fossils to sell, with some of the best-preserved fossils (from the most recognizable dinosaurs) auctioning for millions (Forbes).

Analytical questions

What are the best ways to obtain and preserve paleontological knowledge?

In the Tanis fossil site case study, controversy arose from the site being located on private land and therefore under the control of whoever the land owner gave paleontological rights to. The obvious alternative to this case study is the situation of fossils discovered on public land. So, what are the policies in place for when this happens?

For national parks

- Specimens are illegal to collect from national parks, except when a specimen collection permit is issued. These can only be issued to an official representative of “a reputable scientific or educational institution or State or Federal agency”

- Reputable agencies must only collect fossils for a select group of reasons. The agencies can perform research, collect baseline inventories, perform impact analysis, or create a museum display when the superintendent determines that the collection is necessary to the stated scientific or resource management goals of the institution or agency (US National Park Service).

For land under the jurisdiction of the department of interior:

- The paleontological resources preservation act of 2009 applies. This requires that the secretary will create plans for inventory, monitoring, and scientific/educational usage of paleontological resources

- It also mandates the distribution of research and collection permits and museum curation

- Invertebrates and plant fossils are allowed to be collected by anyone on public land (except for in national parks or fish/wildlife land)

- The bureau of land management is prohibited from releasing the location of bones. This is for the protection of the bones. (US National Park Service)

So, while it depends on the exact kind of public land that the fossils are found within, generally, fossil sites on public land require permits to excavate, and the fossils uncovered on them belong to the federal government. Research museums and universities are able to hold dinosaur fossils in approved repositories for study, but these fossils are never allowed to be bartered or sold. This is in contrast to private land, where landowners are given full ownership over fossils discovered on their land (How Stuff Works).

What about in other countries? South Africa has somewhat stricter laws, requiring permits for any fossils discovered, including plants and invertebrates, and dictating that all fossils are the property of the state. Fossils are not allowed to leave the country except after an application process for the study of the fossils abroad. (The Journal of Paleontological Sciences)

In Mongolia as well, dinosaur fossils cannot be owned or sold and are considered part of the nation’s cultural heritage (How Stuff Works).

Proposal

Returning to our case study, it is important to note that it seems as though the claims that DePalma made about the Tanis site all seem to be true. Other scientific collaborators and peer reviewers have come to similar results and verified findings. This is not to say that DePalma has gone without controversy; a recent paper of his has come under fire for suspicious data that may be forged, and DePalma has received an official complaint for research misconduct at the university or Manchester where he is completing his Ph.D. While this paper’s conclusions match that of colleagues, DePalma may have forged data in order to beat out a colleague and publish the findings first (Science.org).

However, this most recent controversy, if true, seems to be more of a product of DePalma’s personality rather than the fact that the fossil site is located on private property. Yet, the complete control of one individual over such an important fossil site has certainly made other scientists uneasy, and it is understandable considering the potential damage DePalma could do by restricting access to get singular credit for research findings and preventing colleagues from verifying results.

More generally, there are risks that come with giving landowners complete control over fossils found on their land. A highlight of the value of paleontological knowledge is what we can learn about our past from it. Landowners may prioritize fossils very differently, which could result in the destruction of specimens for convenience or the auctioning of fossils to the highest bidder or the most interested commercial paleontologist.

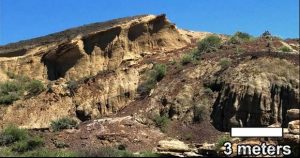

While commercial or hobbyist paleontologists could still uncover and preserve fossils, paleontological information comes from more than just the specimens themselves. The process of uncovering fossils, observing rock layers, and noting how artifacts are grouped together creates an entire story to go along with items. The act of uncovering fossils inherently destroys this geologic context in the process, and so there is really only one chance to get it right.

Scientists certainly do not always do their due diligence when it comes to uncovering fossils carefully and with the gravity of a singular, unrepeatable process in mind (look up ‘bone wars’ if you’d like an example of some rushed and backstabbing paleontologists with goals that seem far removed from the preservation of artifacts or the increase of knowledge). But still, motivation matters. If the goal is to resell fossils or to display some dinosaur bones proudly on a shelf, there is zero incentive to create records of geological context. For commercial paleontologists, working efficiently and finding the most valuable fossils is how to be successful. Maybe these goals aren’t always at odds with science. But they probably are.

Certainly, selling fossils can bring money to the field and create jobs for paleontologists (Fossilera). But it also creates a market for sloppy fossil excavation without documentation of geological contexts and takes research specimens away from interested scientists who could tell us more about our world. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to tell the difference between fossils being sold after being excavated responsibly and studied thoroughly from those that were found solely to turn a profit. This draws similarities to other markets, like looted antiquities being sold to museums or international ivory trafficking. While a 1989 international ban on the sale of ivory did decrease elephant poaching for nearly two decades, the 2007 return of the legal ivory sale on the global market from African countries’ stockpiles has resulted in the subsequent return of large-scale poaching (National Geographic). Or as described in Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino’s Chasing Aphrodite, legal loopholes for the export of archaeological artifacts covered up a massive illegal export industry and caused rampant looting and destruction of artifacts. A legal market breeds illegal ones too.

So, the broader adoption of policies mirroring Mongolia or South Africa’s seems like a clear path forward for improving paleontology. Policies like these already exist in the United States for public land. Of course, this will come with difficulties. But should our knowledge of the world, where we came from, and where we could be going be dictated by arbitrary and temporary land ownership? I think, when it comes to the prospect of the permanent destruction of knowledge, we should consider some difficulties a small price to pay.

References

- A Conversation With: Robert DePalma – 🦖 Dinosaurs: The Final Day with Attenborough – BBC. Directed by The Dinosaur Channel, 2022. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6EIxagTiXvg.

- A Seismically Induced Onshore Surge Deposit at the KPg Boundary, North Dakota | PNAS. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1817407116. Accessed 30 Oct. 2022.

- Astonishment, Skepticism Greet Fossils Claimed to Record Dinosaur-Killing Asteroid Impact. https://www.science.org/content/article/astonishment-skepticism-greet-fossils-claimed-record-dinosaur-killing-asteroid-impact. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

- “BBC One – Dinosaurs: The Final Day with David Attenborough.” BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0016djt. Accessed 30 Oct. 2022.

- Benton, Michael J., and The Conversation. “A Controversial Discovery Could Reveal the Last Moments of the Dinosaurs.” Inverse, https://www.inverse.com/science/dinosaur-graveyard-tanis-north-dakota. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

- “Commercial Paleontology Destructive to Human Knowledge?” FossilEra, https://www.fossilera.com/blog/commercial-paleontology-destructive-to-human-knowledge-really. Accessed 13 Dec. 2022.

- Laws, Regulations, & Policies – Fossils and Paleontology (U.S. National Park Service). https://www.nps.gov/subjects/fossils/fossil-protection.htm. Accessed 30 Oct. 2022.

- Magazine, Smithsonian, and Riley Black. “Fossil Site May Capture the Dinosaur-Killing Impact, but It’s Only the Beginning of the Story.” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/fossil-site-captures-dinosaur-killing-impact-its-only-beginning-story-180971868/. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

- Mitchell, Alanna. “Why This Stunning Dinosaur Fossil Discovery Has Scientists Stomping Mad.” Macleans.Ca, 9 May 2019, https://www.macleans.ca/society/science/why-this-stunning-dinosaur-fossil-discovery-has-scientists-stomping-mad/.

- Paleontologist Accused of Faking Data in Dino-Killing Asteroid Paper. https://www.science.org/content/article/paleontologist-accused-faking-data-dino-killing-asteroid-paper. Accessed 11 Dec. 2022.

- Preston, Douglas. “The Day the Dinosaurs Died.” The New Yorker, 29 Mar. 2019. www.newyorker.com, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/04/08/the-day-the-dinosaurs-died.

- South African Laws Pretaining to the Collection, Import, Export and Sale of Fossil Material. https://www.aaps-journal.org/South-African-Fossil-Laws.html. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

- “Who Owns the Rights to a Dinosaur Skeleton?” HowStuffWorks, 19 June 2018, https://animals.howstuffworks.com/dinosaurs/who-owns-rights-to-dinosaur-skeleton.htm.