27 Conclusion

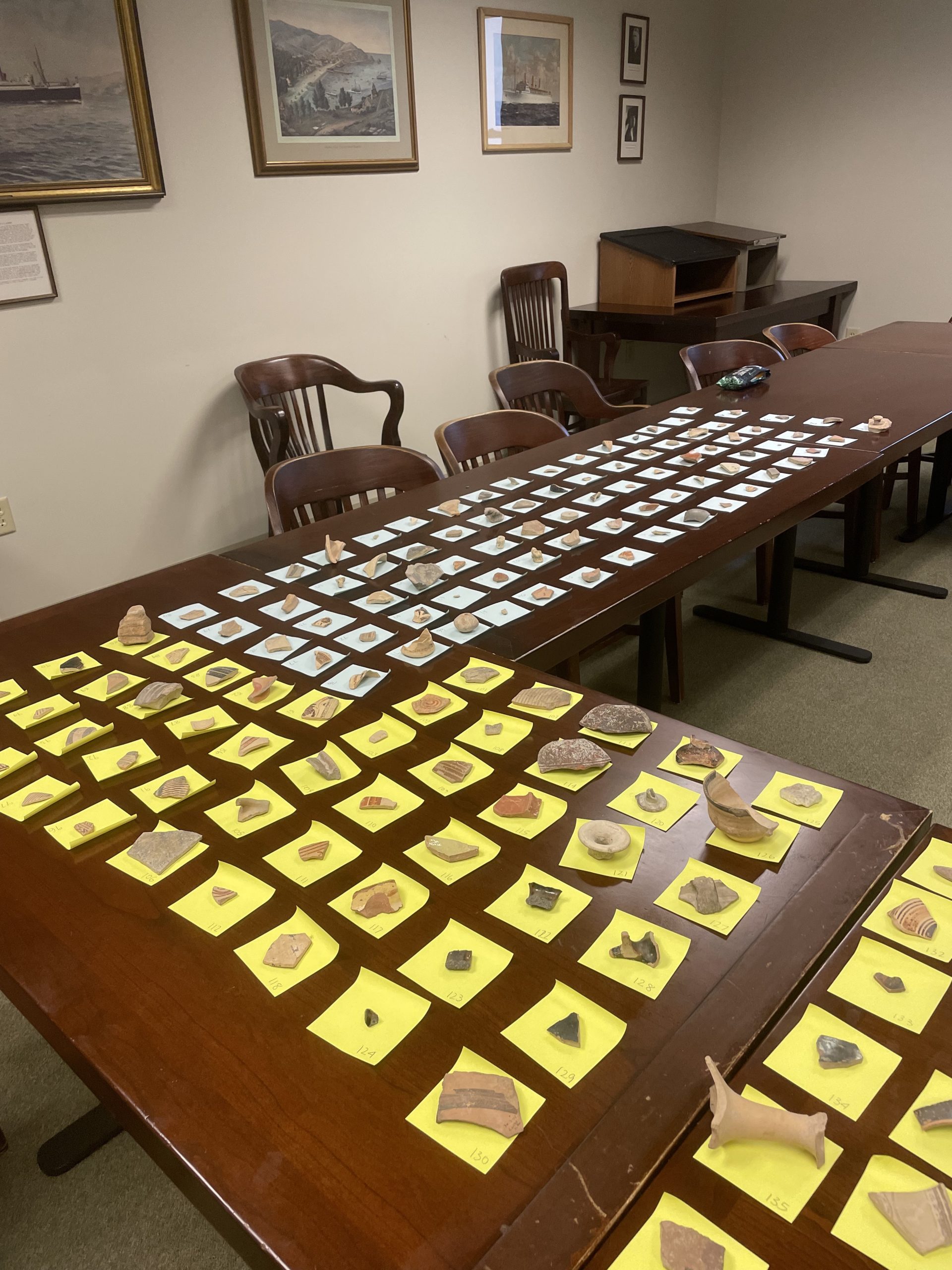

Archaeology has had a long and storied history with colonialism. In the Americas, archaeology was utilized to justify colonization by “proving” that the Native Americans were unable to create an advanced civilization without the intervention of colonists. Archaeological practices have historically served to subjugate foreign lands under the guise of scientific pursuit. In Africa and Asia, archaeology was inextricable from the political ambitions and interests of Western countries. Many prominent archaeologists were in their respective government services, such as Paul Emile Botta and Mortimer Wheeler. Furthermore, archaeology has allowed the appropriation of cultural artifacts “in the name of disinterested scholarship” (Moro-Abadía, 2006). There is a pervasive idea in classical and archaeological disciplines that Western countries will “take better care” of others’ cultural property, entitling Western practitioners to take what they please from archaeological sites. We believe these pottery sherds and other artifacts taken by Harry Carroll exemplify the consequences of this problematic mindset. Because they were robbed of their archaeological context, we do not find it appropriate to study their potential or purported origins. Without provenance, they retain no real academic value. With this in mind, we hope therefore that our project will serve a different pedagogic purpose. We intend for this Pressbook to be thought-provoking in regard to the ethics of archaeology and the handling of cultural patrimony. We hope it causes readers to question: Are we entitled to archaeological artifacts found on foreign or stolen land? What are the drawbacks of owning unprovenanced objects? How can we restore the dignity of looted objects? How can repatriation work to create a more equitable archaeological consciousness?

Additionally, we hope our readers can interrogate the ethics of “collecting” antiquities: the systematic practice of acquiring ancient peoples’ “things” to satisfy a symbolic need. According to thing theory (largely established by Bill Brown), when objects lose a clear sense of purpose, role, and place, they become “things” that elude our understanding. This creates an estrangement of the object’s history and ontological value from the human subject. Instead, the objects collected become symbols of far-reaching power, culture, and intellect for the human subject. While restraining ourselves from “studying” this collection of objects in order to edify ourselves or futilely ascribe intellectual meaning to them, we attempted to challenge these predilections associated with collecting. We aspire for those who view our project to critically assess how they interact with the material world and to consider how they can be more respectful of others’ material culture.

Source cited:

Moro-Abadía, O., 2006. The History of Archaeology as a ‘Colonial Discourse’. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 16(2), pp.4–17. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/bha.16202.