4 Dreaming of Cycladic Objects: an Examination beyond Aesthetics

Dreaming of Cycladic Objects: an Examination beyond Aesthetics

A Pressbook by Emily Church and Maggie Merrill

Professor Jody Valentine

CLAS 117.1, FA 2022

Introduction

In the pressbook that follows, we explore a possible future for Cycladic objects. By examining their histories and previous treatments in museums (the Met, the Getty Villa, and the Cycladic Museum in Athens, in particular), we present our imagined alternative, centering their simultaneous unknowns and uses in responding to their aesthetic pull. As we are drawing heavily from the thinking of Chippendale and Gill, it is only right that we begin with their words. Positioning the scheme of their article, the two write, “(w)e are fond of these objects ourselves, and part of that fondness is in finding them strange and alien; but we do think that our response, founded in our individual selves and for the larger part in the aesthetics of our present society, has little to do with the meaning of Cycladic figures in their own age” (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 604). While we both have different exposure to Cycladic objects and have met them in various contexts, we, too, come to this work from a place of “fondness,” which we will enunicate for you now.

Growing up, Maggie was surrounded by Cycladic art. Her grandfather, who was Greek, would proudly take her to the Cycladic and Acropolis Museum in Athens, demonstrating the progression of Greek art as a source of nationalistic pride. Beaming, he would tell the story of the Greeks reclaiming the parthenon during World War II, while in the next breath praise the artistic vision of Cycladic sculptors. Her mom similarly took interest in Cycladic art, and filled her childhood home with replica statues. Surrounded by this positioning of the objects, Maggie also grew attached to Cycladic works; she frequently carries tote bags with Cycladic prints, has cycled through various Cycladic keychains, and has a flyer from the Cycladic Museum’s exhibit “Picasso and Antiquity” hanging in her room. This past semester, Maggie has been questioning this familial value of Cycladic objects as “art,” influenced by the work of Chippendale and Gill and the class trip to the Getty Villa. In the context of Chippendale and Gill, the way in which the Getty Villa displays Cycladic objects among other Greek statues led to a wondering about how they appear in other museums, specifically the Met and the Cycladic Museum in Athens. While the three museums deal with Cycladic objects differently, they all value aesthetic function over lost realities, leading to a confusing experience in viewing the sculptures. At the Getty, for instance, many of the descriptions seem misaligned with the Cycladic sculptures, offering inconsistent details. Moving from these personal stakes and experiences of disorientation, this reflection has led to a project of reimagining. We aim to establish Cycladic objects outside of their aesthetic role, thinking about how to map lost histories as central to our proposed libraries and dioramas.

Emily also was a consistent frequenter of museums in her childhood. Museums visited in her early life many times were showings and exhibits specifically targeted for children, such as the Hands on Children’s Museum or the United States Holocaust Memorial Musuem: Remember the Children. Many of these children’s targeted museums were also revisited later in life in a different role while serving as a babysitter or as an older sibling. However, she also remembers visiting museums such as the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and the National Air and Space Museum which were still engaging, but not solely targeted at children. Emily recalls that she not only enjoyed her time there in her youth, but also into her teen years. The interactive and liveliness of these exhibits was a a large part of why she enjoyed the spaces and was also able to learn.

In this project, she aims to bring in many of the features of dynamic and spirited museums she has attended. While reimaging Cycladic sculptures’ physical and historical presentation, we wish to draw on much of the interactive nature and elements in these “children’s” museums and exhibits. Even though the presentation of information and objects at these museums may superficially appear elementary or unsophisticated, we assert that this reconceptualization of the presentation of Cycladic sculptures could benefit from the accessible and elemental ideas children’s museums promote and encourage through the dynamic aspects of their exhibits. These elemental ideas may be illustrated in the objet description or in both the exhibition of the objects in space and the formation of their surrounding environment.

Having established our personal stakes, we will turn to the objects’ unknown and known histories.

History

Access to the history of Cycladic objects has been largely influenced by their reception as aesthetic sculptures. As Chippendale and Gill make clear, “(t)he Cycladic case is unusual in that a long standing archaeological concern has recently been joined by a new respect for its aesthetics, which has moved it decisively from an archaeological backwater into the aesthetic mainstream” (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 603). In other words, the aesthetic value placed onto Cycladic objects has not only emerged as separate from their archaeological context, but has established aesthetic function as the primary concern, relegating their histories to the background if including them in the conversation at all. Cycladic objects have gained prominence as carrying aesthetic weight through the work of coinoisseurship and private collectors (the Goulandris Collection, among others), which in turn authorized “illicit looting of cemeteries and other places on the islands where figures and other fine artifacts may be found”; “(i)n this, Cycladic archaeology has suffered in the manner of other areas in the Classical world, notoriously the tombs of Etruscan Italy; in turn it is a prototype for what is now inflicted on, among many instances across the world, sites yielding terracotta figures in Mali, West Africa” (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 603). The very naming of Cycladic objects responds to prioritizing the aesthetic and turns away from this looting: for example, “Cycladic figures are beginning to acquire names, like ‘Cycladic Statue of a Reclining Woman,’ to fit their standing as modern masterpieces” (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 603). Thus, Cycladic objects exemplify a phenomenon that carries into archaeological practices more broadly and impacts other cultural objects, where the very preservation of the materials obscures their origins.

So, what histories are accessible? Much of Cycladic histories reside in fragments, both physically and narratively. Most generally, as their name indicates, Cycladic objects are from the Cyclades, a group of islands located in the Aegean Sea. Looking at their archaeological history, however, they remain absent from “the common canon of ancient treasures in the era of the grand tour” (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 604). The objects have surfaced sneakily, sporadically, and randomly–with the minority being through official archaelogical processes–which makes them hard to catalogue and renders comprehensible histories out of reach. Objects disappear and then reemerge; individuals sculpt modern replicas, as well as illegally dig and hoard. In cases where the context of discovery is identifiable, many objects have surfaced in grave sites as well as domestic or sanctuary sites (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 609). Archaeologists have conducted official excavations on the islands of Antiparos, Paros, Despotiko, Naxos, Amorgos, Syros, Crete, Keos, Melos, and Keros (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 610). Sorting through the unknowns, “Getz-Preziosi estimates the total corpus of known Cycladic figures as 1,600,” but oftentimes the provenance is falsified or completely unknown (Chippendale and Gill, 1993, 608). Thus, we must accept that what we know is scant and that it is scant because of our own archaeological processes. We know that Cycladic objects have been found across the Cyclades. We know that they have been found in graves, domestic, and ritual spaces. We know that they have experienced widespread looting, illegal excavation, and forgery. We have fragments, which begs the question of how to embrace them. Next, we will turn to thinking about how these fragments have been presented in order to later think about possible reimaginings.

Overview of Cycladic Objects in the Met, Getty Villa, and Cycladic Museum

Example Museums and Exhibits: the Met, the Getty Villa, and the Cycladic Museum.

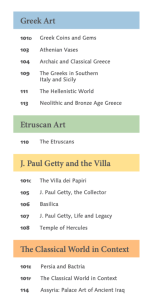

In this section, we will look at the aesthetics and groundwork of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met), the Getty Villa, and the Cycladic Museum. Distinct attention and analysis will be given to placements of Cycladic exhibits in relation to other exhibits and to what these exhibits mean in terms of accessibility.

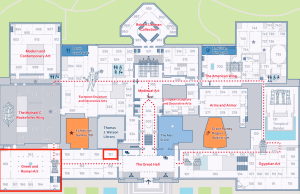

At the Met, there is specific emphasis placed on the Roman and Greek wings of the museum. In comparison to the Greek and Roman wings, the placement of the Cycladic wing conjures a removed feeling. Part of this analysis will draw on my own experience of my recent first trip to the Met. I (Emily) am able to speak from the perspective as a spectator who had never visited the space before, but also as a spectator that has had training in the ethics of anthropology and collection. Initially I noticed the grandiose nature of the Greek and Roman wings and the seemingly dampened room the Cycladic sculptures were kept in. The Greek and Roman wing of the Met is filled with bright light; it is an open space that aims to highlight the monumental work that was created by monumental people. The wing’s main attractions are kept at the end of a long walkway, and can only be reached once walking through smaller pieces of art. Looking at the map below, the Cycladic sculptures are seen in the very beginning of the hallway that eventually leads to the Greek and Roman art. The separation of these pieces in space and by aesthetics helps subliminally communicate to visitors that this work is distant and unimportant compared to the established Greek and Roman art; through space and presentation, the Met illustrates how the Cycladic art is dissimilar to the intellect and wisdom-filled nature of the “true” Greek and Roman artwork.

Finding images of the Cycladic exhibit is difficult, demonstrating their place in the background of the Met’s narrative.

The following objects can be found in the Met’s Gallery 151, in between The Great Hall and Greek and Roman Art:

Similar ideas of separation seen through physical space is also seen at the Getty Villa. In this space, which is much smaller than the many exhibits of the MET, the placement of the Cycladic objects is still separated by multiple doors and always. Seen in red, Room 113 is where a majority of the Cycladic objects reside, when much other of the Greek work is placed at the initial entrance of the museum. This separation in space yet again illustrates the subliminal messaging to visitors about the disconnect between the other Greek art and the Cycladic sculptures. Interestingly, objects such as coins or vases that could be seen as objects of function or tools are not located near room 113 and are instead placed in a group in an area with other Greek pieces: the largest conglomerate area of one “type” of objects seen in the key on the right.

The following image, which we took on our trip to the Getty Villa, features a Cycladic sculpture which the Getty claims is “the only male Cycladic figure in the Museum’s collection. In contrast to the numerous images of females with folded arms, the few depictions of men often show them engaged in some activity, such as drinking or playing musical instruments. In a preliterate society, musicians played an important role not only as entertainers but also as storytellers who perpetuated myth and folklore through song” (Getty, 2003). The Getty assured viewers that all other Cycladic objects were pregnant women.

Regarding the following image, the Getty writes, “Much of the modern esteem for Cycladic figures (and their influence on Modernist art) is based on a misconceived aesthetic premise: that the objects were created with the purity, abstraction, and simplicity of the design and the blank white look of the marble that we see today. Originally, the appearance of most figures must have been much more complex. Facial and anatomical details, and sometimes garments, were rendered in bright paint. The figures were decorated with red, black, and blue designs indicating jewelry and body paint or tattoos. Instead of abstraction there was colorful realism. The addition of paint allowed for differences and variation within a rather uniform sculptural style” (Getty, 2003). Still, the Getty does nothing to alter the perception of the Cycladic objects’ modern aesthetic for the items on display.

For our next analysis, of the Cycladic Museum, there will be less of a focus on the Cycladic pieces in relation to different displays or objects by other groups, simply because the museum surrounds the idea of Cycladic Art, setting it apart from the previously discussed museums. However, in this museum we continue to see the theme of emphasis of aesthetic. The image below taken from the Cycladic Museum website is illustrative of this focus on aesthetic. The pure white background moves visitors eyes away from the background and directly to the objects placed on high display. The way these objects are displayed in an artistic and serene way emphasizes the value of the piece as an object of visual value. This completely takes away from the possibility of the objects having utility and instead separates them as exclusively art.

Reimagining

Having acknowledged unknowns, tensions between aesthetic function and historical use, and other museums’ treatments of Cycladic objects, we can now turn to our proposed museum, which operates upon two key components: the library model and the diorama.

The Library Model:

What if a museum was like a library? This question circulated in the earlier weeks of our seminar and we were immediately intrigued. While libraries are places where knowledge circulates–reliant on sharing and community trust, museums claim to partake in a similar mission. As a result, bringing a library structure to museum spaces might help actualize a shift in how knowledge is shared. For Cycladic objects, in particular, a library style museum would underscore their materiality and center their largely unknown ritual histories, challenging the aestheticization that leads to their correlation to modern art and appearance on tote bags.

A Cycladic object library museum could operate in the following manner:

- For each Cycladic object, our museum will print a supply of plastic replicas, designed to lay horizontally as they were most likely intended.

- The plastic replicas will be available to check out for up to a week at a time. Our museum will keep records in a library-card fashion, in order to track where the replicas are.

- Upon checking out a Cycladic object, visitors will receive a pamphlet describing the object’s possible historical uses, illuminating how they were likely to reside in domestic spaces.

- Thus, visitors will be able to carry Cycladic objects into their own homes, experimenting with how the objects influence their own household practices.

- At the end of each borrowing period, visitors will be asked to write any reflections on an index card and pin it to a communal wall by the entrance to our museum. We will provoke visitors to think about specific questions, including, “did holding this object influence my own relationship to my home?”; “How might this object influence my own domestic routines (like washing the dishes, etc.)”; “Am I better able to understand the functional use of these objects?”; “Could Cycladic objects gain a place in modern society divorced from their aesthetic value?”

- This system relies on community trust: trust to take care of the objects, trust to return the objects, and trust to share any impressions about time spent with the objects.

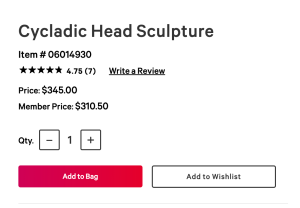

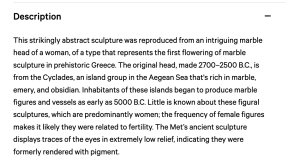

A note on plastic replicas: While our plastic models of Cycladic objects are meant to be functional so that visitors may touch them and carry them into their homes, the idea of making replicas is not new. For Cycladic objects in particular, replicas are widespread and copious–all catered to their aesthetic, modern appeal, however. The Met, for instance, sells a “Cycladic Head Sculpture” in their gift store for $345.00 (the MET Store, 2022). Similarly, etsy has a whole collection of objects classified as “Cycladic heads and figurines’,’ with the price ranging from thirty to hundreds of dollars (etsy, 2022). In these examples, replication is used to uphold the aesthetic value of Cycladic objects. We can think, too, of Mussolini’s “Plastico di Roma Imperiale,” where the dictator commissioned a plastic model of Rome, demonstrating his desire to connect his facist ideals to the foundations of Rome (Sistema Musei di Roma Capitale, 2022). See the images below (from top to bottom: MET, Etsy, Etsy, Plastico di Roma Imperiale).

//

//

//

//

Invoking replication’s ability to transfer values, our replicas will advocate for an understanding of Cycladic figures as objects, with a plastic, durable form underscoring their everyday presence in ritual and domestic spaces. In crafting our replicas, we will use a 3D-printer, aligning our craft with the creation of plastic toys (like a child’s truck), plastic utensils, and items designed to be held and circulated. See images below.

The Diorama:

The living diorama will be a full room in the museum. It will be enclosed by four walls that give the visitors the illusion of being in an archeological site: evoking the locations in which Cycladic objects have been found. The floor of this room will also be covered in some sort of clay or sand—similar to a children’s sandbox seen below. Here, visitors will be able to dig or uncover different objects in the sand. After “discovering” these objects, the visitors will be asked to say what their found object appears to be and what its proposed use is, even if they think they damaged the object or its surroundings when digging it out. This will hopefully promote questions about the ethics of excavation and how it affects sites and places that many times do not belong to the archaeologist or discoverer.

Asking visitors what the object is and what its utility may be will likely evoke some illogical responses from children and adult “untrained” archeologists excavating this living diorama. However, with these responses, museum staff will be able to emphasize the challenges in predicting what objects are with the wear and tear of age in a certain context or lack thereof, even for objects discovered in the same locations. Lastly, this experience will underscore the idea that, even for trained archeologists, these challenges continue to exist.

Through challenging spatial expectations and ideas of form, we hope that our museum clears a pathway for remembering the functional, ritual, and widely unknown histories of Cycladic objects.

References

All3dp.com. All3DP. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://all3dp.com/

Gill, D. W. J., & Chippindale, C. (1993). Material and intellectual consequences of esteem for cycladic figures. American Journal of Archaeology, 97(4).

Getty: Resources for Visual Art and Cultural Heritage. (n.d.). Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://www.getty.edu/visit/downloads/gv_map.pdf

Metmuseum.org. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.metmuseum.org/

Museum of cycladic art. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://cycladic.gr/en

Museum map- MET. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://maps.metmuseum.org/

Plastico di Roma Imperiale: Anfiteatro Flavio. Plastico di Roma Imperiale: Anfiteatro Flavio | Museo della Civiltà Romana. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.museociviltaromana.it/it/collezioni/percorsi_per_sale/plastico_di_roma_imperiale/plastico_di_roma_imperiale_anfiteatro_flavio

Shop for handmade, vintage, custom, and unique gifts for everyone. Etsy. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.etsy.com/

Valentine, Jody, “Lecture: Idols and Idolatry,” CLAS 117.1, Pomona College, September 22, 2022.

Visit the Getty Villa Museum. Visit the. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.getty.edu/visit/villa/