22 Harry J Carroll

Harry Carroll was a Professor of Classics at Pomona College from 1949 to 1983. He helped to create the “College Year in Athens” study abroad program and was a member of the American School of Classical Studies in Greece. Throughout his tenure, he made many trips to Greece, where he amassed this collection of pottery sherds and other assorted artifacts.

The Claremont Colleges Library’s Special Collections is home to the Harry and Olive Carroll Papers and Scrapbooks. It contains lecture notes, articles, photographs, personal correspondence, and scrapbooks. These scrapbooks were created by Harry and his wife, Olive, and commemorate various trips to Greece and world cruises. We explored this archival material to better understand Harry Carroll: his travels, his motivations, and his work. It was through these materials that we learned of his extensive involvement with CYA (College Year in Athens) and his frequent trips to Greece. Although not a trained archaeologist, Carroll facilitated many visits to archaeological sites such as Agora and Chios. His primary function, however, was to lecture and entertain wealthy friends of the College.

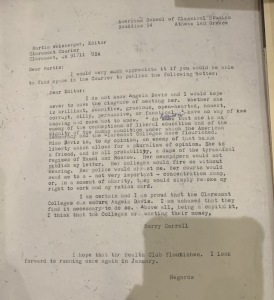

However, some of the more enlightening documents were the countless articles and letters to the editor of the Claremont Courier that addressed Carroll’s political views. A staunch Republican, Carroll wrote in The Student Life (1972) praising Nixon’s record post-Watergate and encouraged students to reelect him, as Nixon “courageously coped with and made significant progress in alleviating many of the cruel problems created and compounded by the so-called liberal administrations of 1961-69.” Carroll believed that “the seeds which President Nixon sows in American political life are not the liberal dragon’s teeth of group and racial conflict, but those of reconciliation and mutual understanding among us all.”

In 1965, Carroll wrote a review of William McNeill’s 1963 book, “Rise of the West,” a world history centered on the great influence of the West. McNeill himself, in a 1990 article entitled “The Rise of the West after Twenty-five Years” described the book as “a form of intellectual imperialism.” Although Carroll’s 1965 review was mixed, he praised McNeill’s hope that some kind of international political organization can prevail in modern times, “like the empires of old.” Carroll also reaffirmed the “predominance” of the West. We highlight these sentiments because it reveals Carroll’s imperialist and colonial attitudes which would have encouraged a sense of entitlement large enough to pluck and hoard others’ cultural patrimony.

In another article written around 1977, Carroll decried the burgeoning social reforms introduced during the time. “I am stretched on affirmative action’s bed of Procrustes. If I have five women and one man in my class in Latin Cookbooks of the Flavian period, it is suggested by that marvelous what-is-it Title Nine that I should be investigated for possible sexual bias, whereas before I had proudly assumed that those Ms’s enrolled because I was an attractive old sex pot. Perhaps, I should, to be faithful to Title Nine (I am a law-and-order-citizen) count the number of masculine and feminine nouns in my reading lists to assure that nothing is assigned which does not have an equal number of each.” He clearly believed he had the right to do things his own way, no matter how it affected those around him. A person with such animosity toward policies pursuing equity amongst his students likely would not have respected others’ rights to cultural objects. It is evident from these attitudes that Carroll would have shuddered at the idea of repatriation. His writings reveal a great sense of personal privilege and dispensation. This archival material allows us a window into his psyche and the ethos of academia during his tenure. The legacy of colonial and imperialist attitudes within archaeology and classical studies is still pervasive today. Thus begs the question: how do we confront this reality?