24 Reflection on American Archaeology

In his article “Alternative Archaeologies: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist” (1984), Bruce Trigger examines the history of archaeology and how archaeological practices are influenced by the politics of the moment. He notes that archaeological digs are present even in countries with few expendable resources, and that the more novice the archaeologist or the method, the more likely the dig is to be in a country with less wealth. Archaeologists tend to present their practice as purely academic, but “while archaeologists generally are caricatured as embodiments of the myopic, the unworldly and the inconsequential, the findings of archaeology have always been sources of public controversy. Many of these controversies have centred around conflicting claims of national priority and superiority.” Thus, it is no surprise that nations that want to assert their political dominance are bound to do so by excavating in foreign countries and bringing foreign artifacts back to the homeland. Trigger defines different modes of archaeology as either nationalist, colonialist, imperialist/world-oriented. For the purpose of this project, I will focus on imperialist archaeology, as defined by Trigger, as that is the context in which Harry Carroll traveled to Greece.

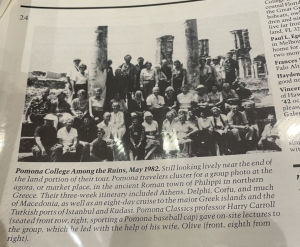

After the second world war and three years of Axis occupation, Greece was immediately plunged into a civil war that lasted three more years. The Provisional Democratic Government of Greece, supported by the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, eventually lost to the Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United States and the United Kingdom. This Cold War by-proxy left Greece in great economic distress, in debt to the United States for military and economic aid. This is the background on which Harry Carroll was conducting his classes and encouraging other American academics to study ancient Greek society and history.

While American classicists tend to uphold Greece as a pinnacle of Western thought and culture, there is still an attitude of American dominance that encourages the usurpation of material culture. Trigger explains the emergence of American New Archaeology in the 1960s claims, “the New Archaeology can be seen as the archaeological expression of post-War American imperialism.” This New Archaeology denied the importance of individual national identities, instead emphasizing the ways in which knowledge can be universally useful. Therefore, it might seem like American archaeologists were valuing Greek culture, but in a way they were appropriating it, arguing that Greek material culture was equally as valuable to the United States as it was to Greek citizens, since in their point of view, Greece is the cradle of all “Western” society. Even if individual archaeologists did not have this intention, American archaeology was ultimately a tool of imperialism. Trigger argues the necessity of “investigating the behaviour of archaeologists not simply as individuals but as researchers working within the context of social and political groups.” With this goal, we can see Harry Carroll as only one player in a larger schema of America’s assertion of dominance over the rest of the world. Despite our frustrations with one individual, we have to remain focused on dismantling the undergirding ideologies that enabled his actions (many of which are alive and well in our own academic institutions), rather than simply “solving the mystery” of our drawer. This is not to say that American archaeology does not continue to have these problems, merely that the scope of our project focuses on recent history.

Trigger, Bruce G. “Alternative Archaeologies: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist.” Man 19, no. 3 (1984): 355–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/2802176.