Flow Chart: An Introduction

Char Miller

Water: it seems so ephemeral, so fluid. Its three states—solid, liquid, and gas—appear to underscore its transitory nature. But water leaves traces, even after it has frozen; or fallen from the sky and flowed to the sea; or evaporated on a burning-hot day.

Indigenous peoples have long known these complex realities, knowledge that has been and continues to be related through oral traditions and a deep-time sense of place. As Teri Red Owl (Nüümü) notes about her people’s homeland—Payahǖǖnadǖ—also known as the Owens Valley in eastern California: “We interpret the name as being the place where water has always flowed or the land of the flowing water.” They have lived, loved, and worked in its company, a companionable reciprocity.

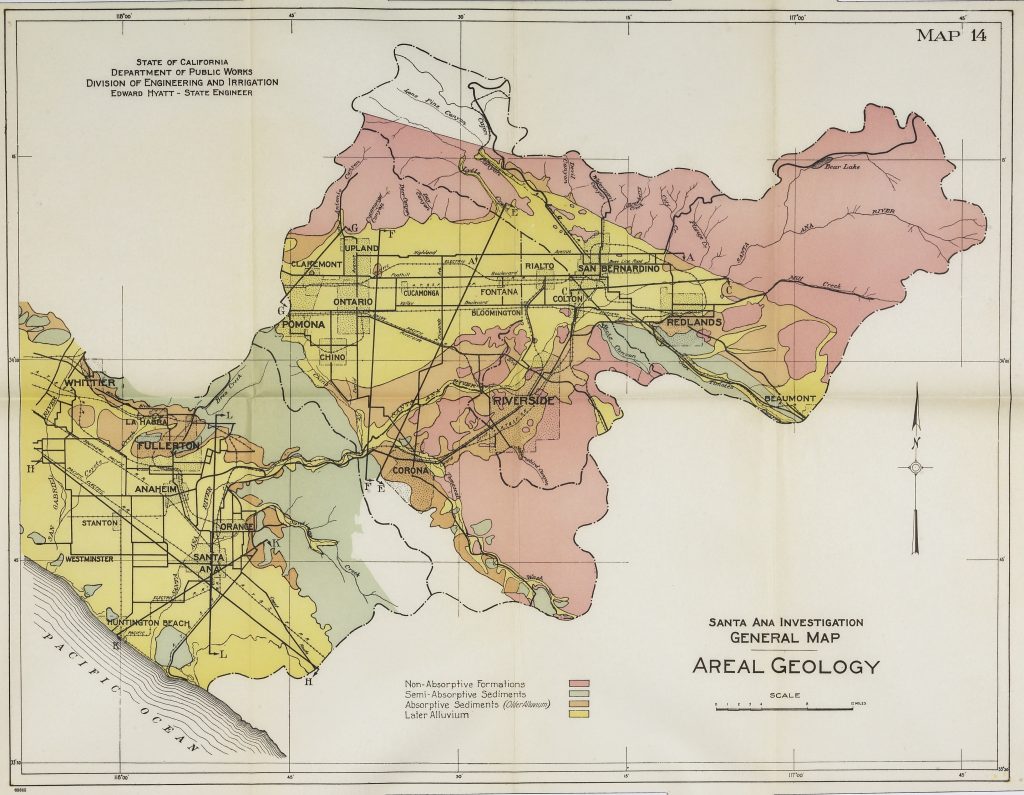

Western scientific enterprise simply confirms this larger insight about water’s tangible centrality, its integrative essence. A geologist might point to a canyon wall and identify the different epochs when water’s erosive force exposed basalt, granite, limestone, or schist. A physical geographer might map different soils as a reflection of the presence or absence of water, much as a botanist might do with regional flora, a zoologist with local fauna, and an ecologist with habitats.

Historians and other scholars, in turn, might head indoors in search of a different form of evidence documenting the interplay between people and water. Like a 1938 photograph located in the Claremont Colleges Library Western Water Archives. It captures a cluster of Scripps College students, some with brooms in their hands, who stand at Honnold Gateway as grit-filled floodwaters flow down the stairs and race south along the abutting Columbia Avenue.

This flash-flood moment in the history of Claremont, California opens a larger story about the college being constructed in the alluvial fan that spreads south of San Antonio Canyon in the San Gabriel Mountains—the apex of the local watershed. Eighteen years later, a dam was built at the mouth of the canyon to stop future inundations, which incentivized the suburbanization of the entire valley below.

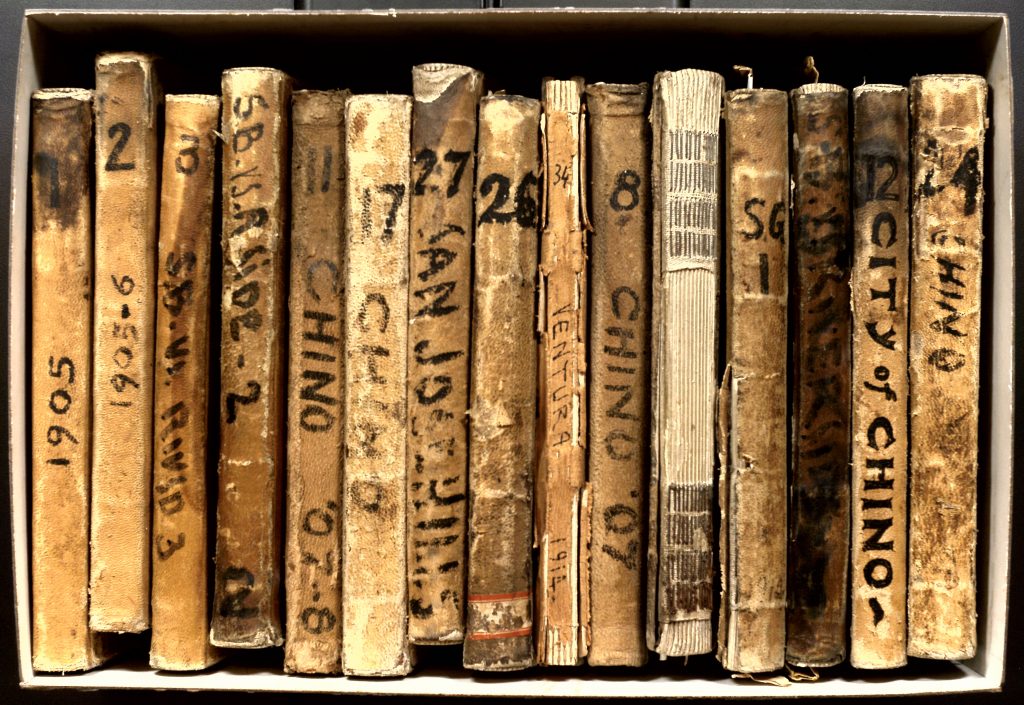

At least that glossy image depicts water’s white-capped surge, its corrosive rush. Texts—handwritten or typed—seem to freeze water in place. Willis S. Jones’ early twentieth century field notebooks record the varied groundwater levels in the Chino Basin (part of the Santa Ana River watershed) and throughout Southern California, scribbled data that did so much to determine who could lay claim to what water, where, and why.

As does the 1928 exhibit brochure for the Boulder Canyon Dam, as well as the faded blueprints, photographs, and maps for the Parker Dam (1939) and related infrastructure; the waters that backed up behind the Parker have been siphoned into the Colorado Aqueduct and then funneled into and helped build an urbanizing southern California. Other documents were written to rationalize the putative need for the Los Angeles Aqueduct (1913), which channels vast quantities of water out of Payahǖǖnadǖ/Owens Valley. Another trove of governmental reports promotes the construction of the State Water Project (1960); this material offers additional insights into the Golden State’s interlocking infrastructure developed to transport precipitation that comes down in one region to another where it tends not to do so.

Such archival research is revelatory. But it is also a privilege. Gaining access to the relevant material is not always straightforward or accessible. To break down any such barriers has been the goal of the Western Water Archives, and with grant funding from the Council on Library Information and Resources and the Mellon Foundation, the Claremont Colleges Library has pursued an ambitious project of digitizing portions of its water-centered holdings as well as related materials in six partner institutions throughout southern California.

To call attention to the diversity of documentation that has been and will be digitized, on March 15, 2021 the library hosted an online symposium devoted to the history and present state of water in California. It drew more than 240 registrants from around the United States; those numbers, when combined with the engaging question-and-answer period that followed the presentations, and the post-symposium viewing of the recording (as of this writing more than 100 people have watched after the fact), testify to the considerable interest in the Western Water Archives and the research possibilities they contain.

The goal of Wading Through the Past is to capture that dynamism. To do so requires setting the context of the ambitious digitizing project at the Claremont Colleges Library. Lisa Crane, Western Americana Manuscripts Librarian at the Claremont Colleges Library, does just that by her careful examination of the detailed process whereby the archive’s many partners identified materials in 20 collections that were to be digitized; developed the template for documenting each item’s metadata; trained and funded students to conduct the digitization; and organized the ever-expanding Western Water Archives website that brings these 13,000 items out into the open.

Once revealed, these primary sources tell a variety of water stories, narratives that often revolve around infrastructure. In this case, the dams, channels, culverts, pipes, pumps and other technology that enables a society to control and distribute water. “People commonly envision infrastructure as a system of substrates,” observes ethnographer Susan Leigh Star, such as rail lines, plumbing or utility wires, a material reality that appears invisible, “part of the background for other kinds of work.” The concept of its invisibility “becomes more complicated when one begins to investigate large-scale technical systems in the making, or to examine the situations of those who are not served by a particular infrastructure.” Whatever its physicality, infrastructure is contingent, a “fundamentally relational concept, becoming real infrastructure in relation to organized practices” (Star 1999, 380).

The organization of infrastructure, and the society, politics, and capital that make its development possible, when combined with its privileging of certain communities over others, helps frame the middle three chapters of Wading in the Past. Heather Williams, a professor of politics at Pomona College, demonstrates how now-accessible data elucidates long-buried stories about power and possession. Consider the city of Redlands, California. How did this semi-arid locale become one of the centers of the southern California citrus industry that required vast amounts of water? Enter the Bear Valley Irrigation Company, the brainchild of Frank Brown. An ambitious entrepreneur, Brown snagged investors from around the world to underwrite his dam-and-irrigation project in the upper reaches of the Santa Ana river that was also a land-development scheme in the valley below. It failed spectacularly when nature failed to conform to engineers’ assumptions about regional rainfall patterns. As Williams observes, this was not the last time that speculators banked on the Santa Ana watershed functioning as they expected.

Debunking his students’ expectations that water in Southern California is a plentiful resource has led Sami Maalouf, a professor of civil engineering at CSU-Northridge, to ask his students to keep track of their personal, daily consumption over a week’s time. The average, which does not factor in landscape watering, was about 181 gallons a day. But it was not until they saw their consumption compared to consumption in other countries that they realized how excessive their daily intake was and how dependent they were on a system of infrastructure channeled water forms far away as the northern Rockies. The goal of the exercise was to show them how and why we use as much water as we do, why those rates of consumption are not sustainable, and to offer pragmatic steps—personal, political, and technological—to change the dynamics of water use locally. With the larger goal, in a region that has been drying out since the 1980s, of altering our deleterious impact of the global water cycle.

Teri Red Owl would also urge a radical reduction in the consumption of water in the city of Los Angeles because this strategy would have a profound implication for Payahǖǖnadǖ/Owens Valley. After all, her homeland supplies the water that Angelenos use to shower, drink, cook, and, most of all, irrigate lawns and fill swimming pools (upwards of 60 percent of urban water use is deployed outdoors). The construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct may be the conduit of the roughly half-a-million acre-feet per year, but to secure this flow the Department of Water and Power bought up water rights from white ranchers and farmers. It also manipulated the Indigenous inhabitants of the Eastern Sierra as it purchased individual allotments, dried up local employment opportunities, and wrote a report about the “Indian Problem” that alleged the Nüümü/Paiute people were homeless, squatters, and water-wasters. It then schemed with the federal government to force the Indigenous population to live in minuscule reservations on the edge of the towns of Bishop, Big Pine, and Lone Pine. For the past ninety years, they have been contesting their brutal dispossession: “Not only are we seeking the return of land and water,” Red Owl writes. “We’re also fighting to save our homelands.”

Systemic issues of settler-colonialism, racism, and global capitalism revolve around water exploitation in Payahǖǖnadǖ and the rest of California. To better understand the interplay between these issues, and the infrastructure that makes them possible, requires that the Western Water Archive (or any other) be fully accessible and visible. Jeanine Finn and Catalina Lopez address this requirement in the final chapter, noting that their efforts are underwritten by a grant the library received from the Mellon Foundation’s Collections as Data initiative. The project’s goal is ambitious: “to make already digitized heritage materials more accessible to computational methods, as well as surface the histories of groups and individuals that have been marginalized by previous archival approaches.’ Achieving those ends has become difficult when the Claremont Colleges closed in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. One year later, the project lost one of its key collaborators, Tongva elder Julia Bogany. Her demise and the pandemic lockdown forced the library team to pivot and focus their examination on an array of reports containing datasets, such as dam discharges and streamflows, to increase their “computational accessibility”—not an easy task, they note, but a crucial step to making such information–and the social context in which its has been produced–transparent. In the meantime, the librarians remain committed to their original aspiration to “bring Native communities and voices into conversation with these archives” and have begun to meet with the Tongva, the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission, as well as with the Pechanga and Cahuilla to gain “a better understanding of what their current projects are and what their needs might be.”

These commitments are essential, not least because they will help the Western Water Archives come more fully into its own, allowing it to shift, expand, rise, bend, and percolate—just like its titular subject. And like water, nothing about these principled archival efforts is ephemeral.