2 When Water is Money, Drought is the Taxman: Tales of Boom and Bust on the Santa Ana River

Heather Williams

About a million years ago when I was first hired at Pomona College, I had this magnificent adventure driving across the country to Southern California from Pennsylvania. I had been working on soft money, which means almost no money. I tell you, I miss those days when I traveled in my beat-up Ford Escort hatchback from wherever I had made just enough money to live for a while to wherever I could make about the same. At the time, everything I owned fit in the back of that car.

And because the summer before I’d been at the University of Pennsylvania, I’d been unhoused while I finished my dissertation on the road between New Haven and my home in Kansas. I took a southerly route through the Atlantic states where I sat for a time on the porch of my great grandmother’s cabin in the woods of North Carolina, writing on one of those first-generation laptops. There were chapters that got edited in campgrounds and at a series of Waffle Houses somewhere between Charlottesville and Memphis. Aside from my books and that always-about-to-die computer, I had a tent, a cookstove, a sleeping bag. At the time, I thought I was low on my luck. But looking back, I never felt freer.

On my way to California, one of the most magnificent finds was pulling off the highway and driving into the Kaibab National Forest on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. A great deal of it has since burned, and now the charred skeletons of pine trees dot a landscape of young aspen and oak. In the summer of 1998, however, the forest still was dominated by a curtain of deep-hued evergreen. I drove at sunset through the forest and sometime after dark pulled off on a dirt road and drove a few hundred meters to a clearing and bedded down for the night.

At dawn, I woke up to find my sleeping bag in a meadow of wildflowers, piñon, and ponderosa pines. A deer and her fawn were grazing just a few feet from me. We stared at each other open-mouthed for what seemed like a long time.

Like so many other sojourners in the US West, I felt that I had discovered a private paradise, that I must be the first to see this beauty in this little alcove of the woods.

I spent the day hiking the Grand Canyon, later writing in my diary in all superlatives, sketching the landscape badly but enthusiastically. On the second day, feeling expansive, I browsed in the National Park bookstore. I had only a bit of cash, but felt moved to pick up a book that, from the cover, looked properly dark and intellectual. It was a sepia-toned photograph of an expired palm tree in a parched desert, a late paperback edition of Cadillac Desert, Mark Reisner’s classic history of Western water folly. I remember taking it back to my secret little meadow camp and reading it with a great sense of purpose. What was the desert anyway? How did people round up enough water to support this sprawling civilization in a place where I hadn’t seen rain threaten once, and where I hadn’t seen a pool of freshwater outside a swimming pool since central Kansas.

At that time, despite some quibbles I would now have with parts of it, Reisner’s book was an important read for me. I realized that despite the fact that I believed that I had been doing nothing but looking at and falling in love with the land, especially the wide open spaces that go from the grasslands of the lower Midwest to the Rocky Mountains, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in New Mexico, and then red rock and basalt canyons around Gallup, there was a lot that I wasn’t perceiving about the West. With Reisner’s prompting, I woke up to the reality that wherever I saw people or industry or mines, towns, yards, orchards, farms, there was water being wheeled to it.

The ideas the Reisner’s book conveyed to me and the millions of readers since it was published in 1986 were:

- The limiting factor to agriculture and settlement west of the 100th Meridian is precipitation.

- Despite the warnings of surveyors like John Wesley Powell that the government should limit human settlement and form administrative units that corresponded with the West’s major watersheds, the federal government probably locked itself in to costly interventions in water in the 20th century by encouraging uncontrolled private sector development of Western lands in the 19th century.

- As a result of government policy, people adopted really crazy, destructive, and murderous schemes to size land and water sources and irrigate great expanses of land.

- Colossal failures ensued. Horace Greeley’s utopian town at the edge of the Rockies ended up in violent battles over water with Fort Collins and Boulder. Major aquifers were tapped out in the Central Valley by the late 1920s, only about 30 years after newly invented gasoline pumps made deep groundwater widely available to farmers. Speculative wheat ventures in western Oklahoma and Kansas turned to dust in the early 1930s when multiyear droughts in the early 1930s sent dry winds over prairie grasslands torn up by single-disk plows. Conflict over rivers in California overran the court systems when ranchers and farmers settling in river basins found their fields and pastures covered in mine tailings and sediment from hydraulic miners blasting out the banks of the upland tributaries. In southernmost California, irrigators who decided to convey Colorado River water into the low-lying plain of the Imperial Valley in the Sonoran Desert accidentally reversed the flow of the entire river for two years and created the desolate, vast Salton Sea.

The upshot: there was no game at which the private sector won and lost so spectacularly as in the US West.

Southern California is certainly part of the story of the arid U.S. West after 1848, and the story that most people learn about the region is one of Original Sin: the water heist by the City of Los Angeles in which the Owens River draining the eastern Sierra Nevada was sent southward via aqueduct through dubious land and water rights purchases.

This story of stolen water dominates the narrative of Southern California water. Reisner discusses it in a chapter of Cadillac Desert. Prior to that, the great Southland journalist and social theorist Carey McWilliams reported on it in Southern California: An Island on the Land. This story was retold by screenwriter Robert Towne in an even better-known fictionalized treatment, the Oscar-winning film, Chinatown.

The narrative of water theft launched by the (rightful) moral outrage caused by the Los Angeles Aqueduct gave rise to a literature on Big Water in the U.S. West. Whether it was the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power or the Bureau of Reclamation or the Metropolitan Water District, the noir reading of water conveyance at large scales became on in which moneyed interests and speculators capture government and create untouchable, politically locked-in institutions that overpower small actors: small towns, small farmers, small tribes.

The Big Water story, I want to argue, isn’t all wrong. These are powerful and connected agencies, and they serve powerful clients: cities, big utilities, wealthy landowners and real estate developers.

But the story of water folly and politically created drought leading to the Big Water State, or Chinatown if you will, is a parsimonious but only half-true story about how water works in Southern California. And if we take time to look carefully, with an eye to the history of land and water development in the region, especially in the Inland Empire and Orange County, we will emerge with a much better understanding of: 1) where our water comes from; 2) how and why it’s managed the way it is—not by a single large entity, but by around 200 public and private entities; 3) who has claims to it and why. This story is richly represented by the Western Water Collection, where one can see, over time, how small actors in the Inland Empire and Orange County pioneered new technologies while learning how surface water and groundwater actually worked in this geology with its faults and deep sediments, its floods and droughts, its deep aquifers and gushing artesian wells, its booms, its busts, its lawsuits, its landmark court settlements.

Moving Waters

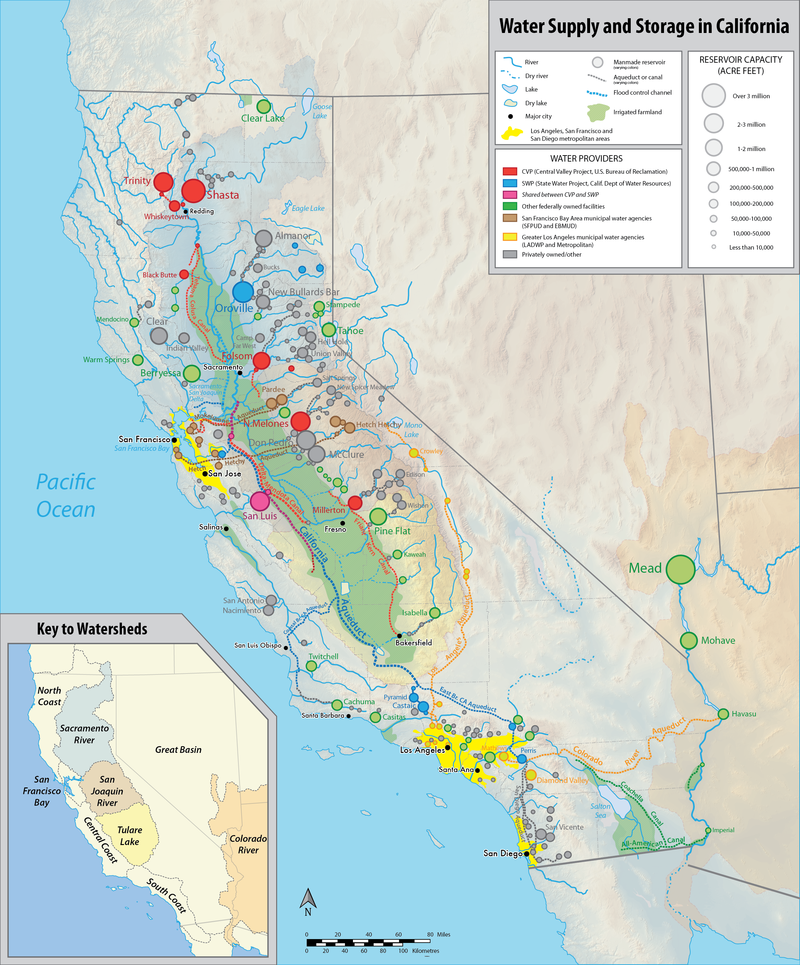

So first, a word about where our water comes from—

When you open your tap, it is true that some of the water comes from the Colorado River or the Feather River via the Colorado River Aqueduct (built by the Metropolitan Water District in the 1930s) or the California Aqueduct (built as part of the State Water Project in the 1960s). In Claremont, that would come courtesy of the Three Valleys Water District, which is what we call a wholesale water district that sells to the retail water districts that maintains municipal water systems here in Claremont or Montclair or La Verne, etc. The other half of your water comes from wells tapping the groundwater basins under our feet. That’s water that comes down from the mountains to the north of us. In places east of us like San Jacinto and Moreno Valley, they use water that falls on Mount San Jacinto.

If we follow that local water back to its source, examine how and why it’s allocated the way it is, there is a lot we learn about the built environment—why some towns have capacious land parcels, green lawns mature trees, wooded parks, while other cities have treeless, mostly hardscaped streets with warehouses, industrial parks, and (mostly now shuttered) military bases.

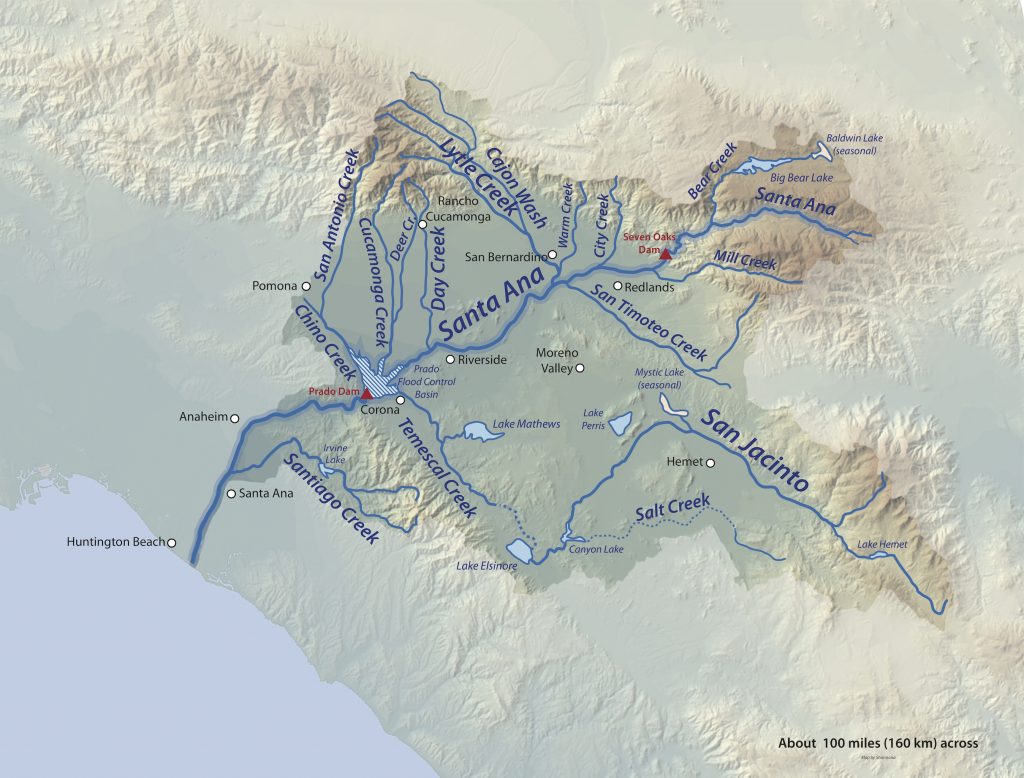

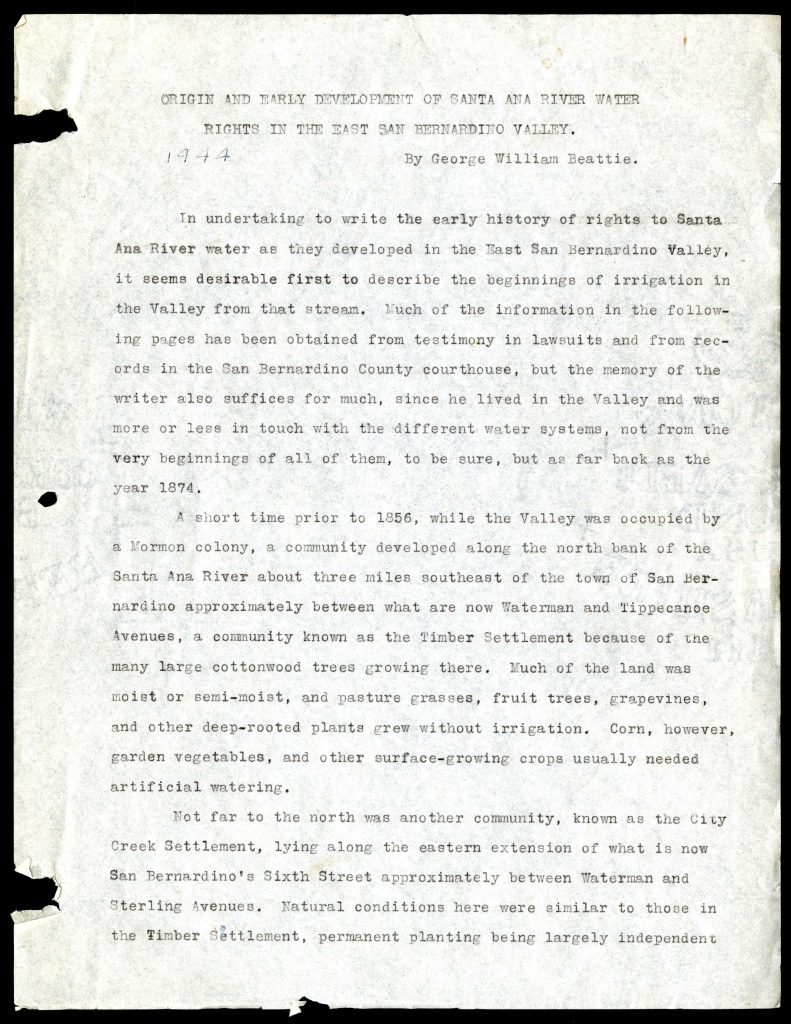

The river basin I want to draw your attention to is the Santa Ana River. For anyone accustomed to rivers in northern California or in the upper Midwest or the East, it’s certainly not much to look at as a water body. It’s a small river—often discharging no more than 700 cubic feet per second. It’s short, stretching just 96 miles from watershed to ocean.

The basin is large, though, covering 2600 square miles and four mountain ranges. In terms of water supply and human use, though, it’s one of the world’s hardest-working rivers. The key to this is what’s underground—the river is small on top, but its waters percolate into thirty capacious groundwater basins. The busiest groundwater in the basin in the world—with more take-outs and put-ins (injections of water from surface deliveries) for potable water than anywhere else on the planet.

This river and its basins have a sprawling history. For the purposes of this talk, I want to tell you just one interesting story among many—a tale of two cities. What I hope to do is to point out how water development over a century ago, in the late 19th century, affects who has what today. This story is about two cities whose built environment and whose water were developed by one ambitious man. At their inception, they were developed with the same market tools and the same water conveyance technologies with the intention of creating two wealthy garden cities. Their trajectories, however, could not have diverged more. One is the city of Redlands, which, along with Claremont, is one of the two outlier cities in an overwhelmingly working-class, warehouse-dominated Inland Empire. Redlands, like Claremont, is known for its tree-lined boulevards, verdant parks with outdoor stages where concerts and films show on summer nights, its museums, its historic homes, its white-collar jobs at Redlands University and ESRI (home of ArcGIS). The other is the sunbaked, spare city of Moreno Valley, known more for its freeway exits than for its attractions. Incorporated in 1986 and lacking a city center altogether (even the City Hall is housed in a generic industrial park), Moreno Valley is largely a center for mega-warehouses, with mass-built, contemporary subdivisions built in easements between industrial parks. In general, Redlands households are small, well-off, with educational levels that smooth income fluctuation. In Moreno Valley, households are larger, working-class, with educational levels low enough to create income volatility. (Median household income in Redlands is 75 thousand dollars, with households averaging 2.8 people. 44 percent of adults have college degrees. Median household income in Moreno Valley is 63 thousand dollars, with household averaging 4.1 people. 11 percent of adults have college degrees.)

What I shall argue is that these two cities, which look so distinct today and that have very different future outlooks and even very different public health profiles, were put on their distinct tracks by a history of water speculation that occurred 130 years ago. At that time, charismatic engineer and dream-seller of Southern California, Frank Brown, made an audacious plan to transform the Santa Ana River into a spigot of real estate wealth whereby its waters would be sent in aqueducts and flumes first to dry lands south of the city of San Bernardino (where Redlands is now) and then later to a dry, grass and chaparral valley south of the Box Spring Mountains and the San Timoteo Badlands about 10 miles away.

I shall argue that the way Frank Brown did this, using private sector money that he raised on international capital markets. He audaciously—some might say recklessly–employed untested techniques of dam construction, groundwater extraction, and long-distance water conveyance.

He would end up fortifying one city—Redlands—with water rights in perpetuity to much of the snowmelt from the western and southern slope of the San Bernardino Mountains, stored behind the dam that holds back Big Bear Lake.

He would then, through investment overreach and inadequate understanding of California’s multiyear precipitation cycles, leave another city—Alessandro—now Moreno Valley (“Moreno” is Spanish for Brown), with dry aqueducts, empty reservoirs, and unpayable debt.

One city would rise in prominence and wealth in the 1890s as the gracious green Arcadian home to millionaires and gentleman farmers selling citrus and the image of wholesome California sunshine to the world.

The other would become a desolate city on wheels where only a few holdout alfalfa and dryland wheat farmers would remain, and where development would come haltingly (and with plenty of air and water toxins) courtesy of the United States Army and Air Force in the mid-20th century.

The story I will tell in brief is taken from a book I never seem to finish on the Santa Ana River where I point to a time in Southern California history in the 1880s which I argue is a pivotal time in the making of the built hydroscape of the region.

At that point, just 30 years into statehood, it wasn’t clear what this region would be.

It was first and foremost a time of savage dispossession of the people to whom this region belonged. Despite the scale of dispossession, the immiseration of the Tongva, Luiseño, Cahuilla, Serrano, Chumash, Cupeños and others was either ignored or romanticized as a part of a bygone Spanish era.[1] Few acknowledged that tribes had been denied recognition altogether by the U.S. federal government. Recommendations for treaty land allocations had been ignored by Congress in the early years after statehood, and Native Californians had been the target of bounty hunters paid by the California legislature in the north of the state; in the south, Native Californians were displaced from lands by settler militias and faced starvation and forced labor.

Among the Anglos who were flooding into the region, a sense of destiny permeated Southern California (fueled no doubt by the hope that gold strikes and merchant fortunes of the north would be replicated in these hills) disappointing early returns in mining and an anemic trading economy in the then-ragged settlement of Los Angeles (so ragged in fact that paper tickets were often used instead of coins and paper bills because there was little liquidity and banking) made for a great deal of speculation about where or if big money could be made here.

Ultimately, it was neither gold, nor farming fortunes, nor deep harbor traffic that brought money to the region, but instead a fare war on two competing railroads that had extended lines from Needles, California south to Mohave and through the Cajon Pass to Southern California. One-dollar fares to Southern California from Kansas sent reams of curious tourists out to see the Pacific Ocean. On the way, many decided to stay, charmed by the balmy climate and ebullient boosters pressing pamphlets into the hands of visitors.

The 1880s marked a time when land speculators and wealthy health-seekers rubbed shoulders with shepherds, cowboys, grifters, penniless immigrant ditch-diggers, tight-knit groups of colonists, hoboes, vagrants, and tuberculosis patients and sufferers of what was then called neurasthenia, a mental disorder believed to be caused by the speeding up of public life in the age of the telegraph, the railroad, the factory, the streetcar.

Southern California was a land more imagined than understood by doctors who sent their patients west. Booster pamphlets and advertisements emphasized open valleys, sunshine, desert air, gardens, and a rural pace of life but with urban amenities, including electricity, running water, and modern transport. This image of empty “semi-tropical” land as a garden in wait of a developer and a willing settler gave rise to what would ultimately be Southern California’s most profitable industry: selling itself. If Southern California in reality little resembled the found paradise that the railroads and land boosters promised, there were people who seized on the idea that with a little ingenuity and a lot of engineering that it could be made into a garden landscape.

The Making of Redlands

A young Frank Brown, who arrived in the City of San Bernardino from his studies at Yale University, was one of a great number of people at the time who embraced this idea of transforming arid chaparral lands into verdant evergreen gardens with irrigation.

What distinguished Frank Brown from others who failed in initial attempts at land-and-water ventures in places with romantic names like Redondo Beach or Alhambra or Rosedale was that Frank Brown, along with a New York Stockbroker, Edward Judson, developed a solid water right from an unlikely piece of risky water engineering and conveyance.

Much like land developers around Southern California in the late 1870s and early 1880s, Brown and Judson knew that they needed water to develop a new colony.

And frustratingly, even though there was a good deal of land that could be purchased nearby and a snowcapped mountain range right above San Bernardino, the river that drained it—the Santa Ana and its tributary, Mill Creek—were modest and fickle flows of water. Though winter storm could bring floodwaters that moved boulders the size of biggies along the alluvial fans, and spring snowmelt would swell the river to a reasonable size—the rest of the year, the river dwindled to a trickle and Mill Creek to a moderate-flowing stream.

A graduate of the Yale Sheffield School of Science with a year of civil engineering under his belt, Brown became convinced that there was far more water in the river than met the eye. Seeing the steep slope and alluvium in this new mountain range, Brown made a bet. He convinced his stockbroker friend Judson and local banker Louis Edwards that he could buy some existing water rights to the surface waters of the Santa Ana River, and supplement that flow by driving pipes into the gravel and rock on lower slopes of the San Bernardino Mountains adjacent with new forms of engineering and that the three of them could make a fortune buying dry land, subdividing it, pairing the land with a certificate promising water delivery, and then selling it at a multiple of the initial acreage price.

What could possibly go wrong?

Well, as it turned out, everything.

Judson and Brown initially needed enough money embark on their water prospecting. They bought a modest 1,500 acres, subdivided the land, and released it at auction in 10-acre plots, 500 acres at a time, promising buyers water rights to water they had not yet found. Buyers were a mixed group and a little sketchy. A lot were property owners from San Bernardino, Riverside, and Los Angeles buying on credit themselves, hoping to sell the plots to new arrivals, even if they ended up with little value as agricultural lands.

In developing their initial land-and-water scheme, Judson and Brown made two mistakes: 1) they underestimated the price of existing water rights (in the mid-1880s, water rights in the region were rising so fast that many rights holders who had excess water refused to sell and used the water frivolously to retain their appropriation); and 2) they underestimated the amount of water each acre would require to grow the sort of orchards and gardens that graced the booster pamphlets promoting Southern California to moneyed tourists (Judson and Brown calculated that each acre of land would require about three feet of water annually. Orchards required about twice that).

The troubled land-and-water development in what is now Redlands likely would have been one of many land schemes gone bad in the 1880s had Frank Brown not been possessed by the idea that he had the engineering skills to produce surface water from subterranean flows.

It’s important to point out that at this juncture, it was widely understood that there was abundant water underground in this arid country. People dug wells. Springs, seeps, marshes vernal pools, and artesian wells dotted the landscape. But aside from the most copious artesian well fields, irrigating from these sources could be tricky—they often fluctuated with the wet-and-dry cycles of California’s climate. There was also no way of flood irrigating with a well, as gasoline pumps had not come into commercial use yet.

Facing ruin, Frank Brown began experimenting with various ways of harvesting water. He observed, for example, that the zanjas, or irrigation mains, spilled over in the winter storms. He acquired a small water right with a storage scheme, building a reservoir to catch runoff from the Sunnyside Ditch that ran from the south fork of the Santa Ana River to lands nearby.

He drilled a tunnel into the bed of the Santa Ana River at a steep grade to convey water through gravity from under the visible riverbed into his new reservoir. (The idea was to drill until he hit bedrock, then forge and underground “Y” to either side to capture river flows that were not part of the water claimed by existing rights-holders.) Brown and his workers dug nine feet into the river bed, then excavated for a distance of 600 feet to a depth of 21 feet at the ends of the “Y.” This Herculean effort, however, yielded a flow that would have been about 210 acre feet of water (of approximately 9,000 acre-feet they would need). He then dug another tunnel that yielded about 910 acre-feet.

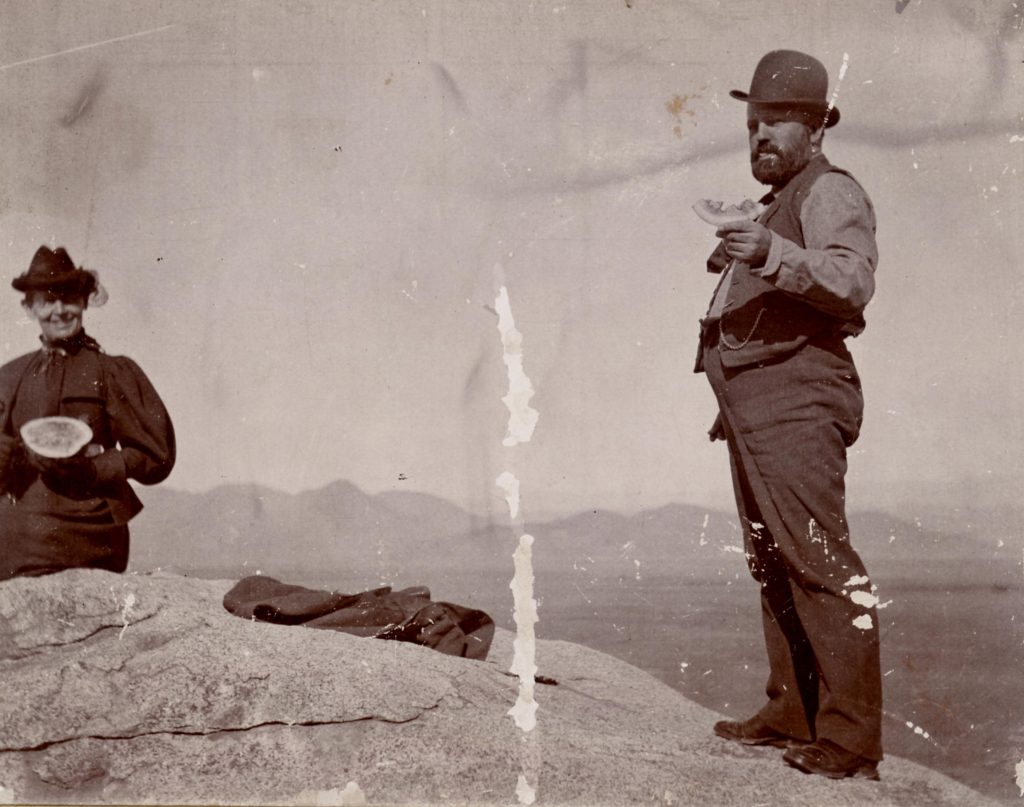

Realizing that they needed thousands more acre feet of water to stave off bankruptcy and scandal, Brown began considering even bigger and riskier measures. Some combination of desperation, arrogance, and irrepressibly drove Brown to take up the invitation of a wealthy local rancher, Hiram Barton, to travel to the top of the San Bernardino Mountains to examine possibilities for engineering at the tributary headwaters of the Santa Ana River. At the time, the only route up the vertiginous slopes of the San Bernardino Mountains was through the Cajon Pass to the north side of the mountain range, up through the Lucerne Valley and into the Holcomb Valley, where snowmelt from Mount San Gorgonio, Butler Peak, Sugarloaf Mountain flowed into streams and ephemeral wetlands.

Convinced that water storage could be built there, Brown returned to Redlands to consider what could be done.[2]

Damming the headwaters of the Santa Ana River at Bear Creek, however, was no simple matter. It meant capturing snowmelt from 11,000-foot peaks behind a dam at the western end of the valley.

At that time, dams were almost all small gravity impoundments that weighed more than the water they held back. Such a dam in the Bear Valley, however, would have been impossible given a catchment of over 100 square miles that might well send tens of thousands of acre-feet of water into Bear Valley in a rapid spring thaw after a wet winter.

With one year of civil engineering training under his belt, Brown began shuttling potential investors up and down the mountains in the summer of 1883, selling the idea that a dam holding back the snowmelt of this mountain range could be built using an arch dam. This dam, unlike a gravity dam, would be thin and light, and would hold back water hundreds of times its mass through principles of compression.

Brown had no experience building such a dam at scale.

Brown had actually never seen such a dam.

But somehow his combination of youth, physical vigor, East Coast credentials, and boundless optimism brought in 360 thousand dollars in backing from six investors, including his friend Judson and the rancher, Barton.

The following year, Brown would lead one hundred men with a train of pack mules carrying Portland cement tools and supplies up grades of 25 percent or more on loose shale up through the pass at Gold Mountain and Nelson Ridge.

In the precipitous Bear Creek Canyon, workers scaled the walls of the ravine, dug a diversion for the creek, and then and excavated below the natural watercourse to bedrock. Laborers earning 15 cents an hour then quarried 1,200 pound granite blocks, moved them on wooden sleds down from a ridge on the east side of the dam site where other workers had built a quarry, then built the dam, complete with a waste weir, and hung a 20 by 24 inch metal gate for water releases.

Today, in an area of intense regulation of dams and river basin structures, the sheer insanity of this project boggles the mind.

That winter, when 94.6 inches of snow fell on San Gorgonio Peak (two times the average precipitation at that time), the reservoir behind the dam filled with 58 million tons of water in a lake that stretched six miles to the north and east of the dam. At one point, water slightly overtopped the structure.

This water weight seven thousand times more than Brown’s dam.

It was maybe the audacious student lab project ever.

And despite all the reasons it might well have failed, it did not.

The dam was eight feet wide at the base and approximately three feet wide at the top.

The influential civil engineer Edward Wegmann extolled the dam as “a structure that surpasses in boldness all other dams being built.”

The dam’s construction and weather testing made Brown a celebrity. Newspapers around the world in the U.S. and Europe hailed him as the architect of the Eighth Wonder of the World.

With respect to his real estate venture, Brown now had a claim to 25,000 acre-feet of water that could be released from the dam and captured in the valley below in the driest months of the year. It would more than provision the 1,500 acres in his existing holding. It was enough to build a veritable land empire.

The settlement built on Brown and Judson’s land venture was incorporated within three years of the dam’s construction. The City of Redlands, established with an elegant town center and subdivided in handsome 10-acre plots that were paired upon purchase with ample water shares, was astonishingly successful. By 1890, Redlands, along with neighboring city Riverside, was among the wealthiest cities in the U.S.

Why? Were the orchards, which were mostly citrus, so profitable?

No.

In fact, no one yet knew how to find a market for oranges in the quantity that were being produced (and would not do so until the 20th century).

The land itself didn’t generate wealth so much as attract it.

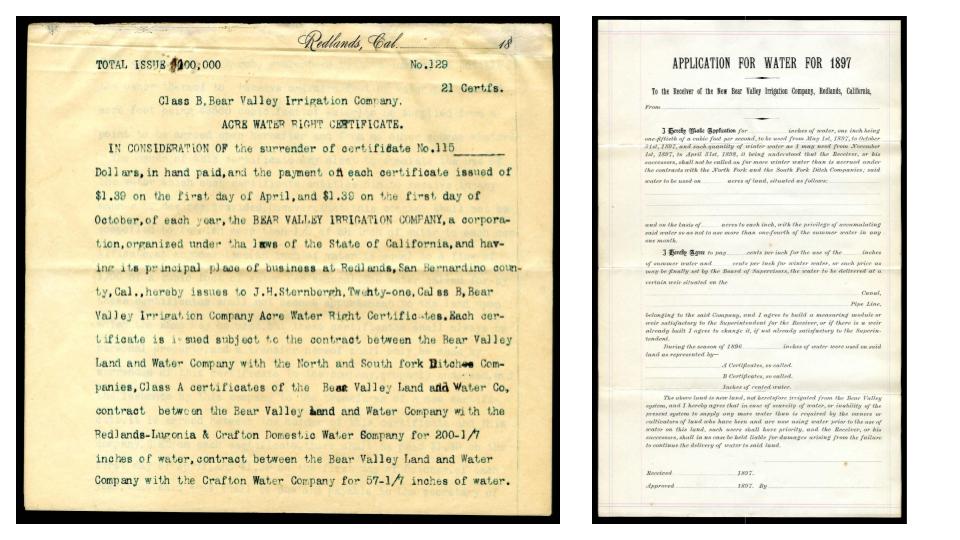

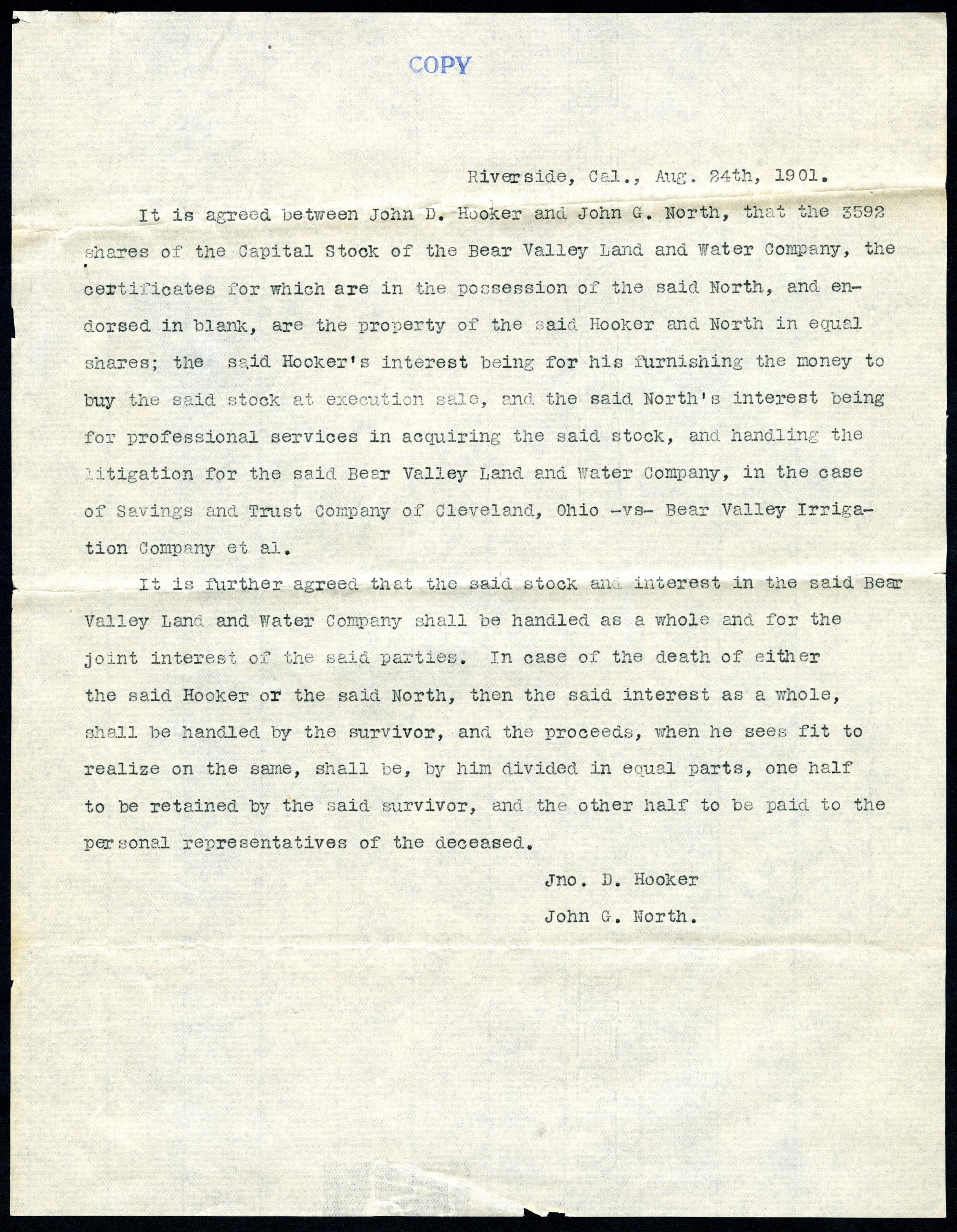

The capital stock of the company, the Bear Valley Land & Water Company, with an initial issue of 3,000 shares with $100 face value, expanded to 7,200 shares for a capitalization of 750,000 dollars (the equivalent in today’s dollars of about 120 million dollars in today’s dollars).

Redlands became a garden oasis, with electricity generated from Mill Creek. Washingtonia palms and roses lined the streets and filled the medians of its principal avenues. So appealing was this city sprung from chaparral flats that the Santa Fe Railroad built tourist spurs through the city’s groves in excursions designed to attract well-heeled investors to its developed homes and orchard sites.

At 5,000 dollars per 10-acre lot (land that had been purchased at between two and four dollars per acre), the inventors easily made back their money.

As mentioned, there was also another way that water was turning into money—securities—buying into the venture itself. This was science making plenty in a field of scarcity, making the desert bloom with siphons, weirs, tunnels, sluice gates, pumps, and concrete (and not mentioned—a lot of cheap labor, much of it foreign-born).

In the early years of Southern California, it was Redlands, much more than Los Angeles or Venice Beach that represented glamor and the good life. H.H. Sinclair, who would go on to found Southern California Edison, candy moguls Alonzo and Irene Hornby, mining magnate George Bowers, Snap-On clothespin heiress Gertrude Hicks, newspaper and land titan William Holt lived ostentatiously on the principal avenues of Redlands.

Even though the city became wealthy by importing millionaires, the idea that real-estate development—the Arcadian garden city with all the tranquility of the countryside and none of its drudgery and isolation—was the real California gold quickly caught the imagination of would-be settlers in inland Southern California. It also fired the imagination of investors captivated by the idea of California as a new Eden, reclaimed from the drylands (imagined in many accounts as a postlapsarian landscape, the product of sin) by the science of irrigation.

By this, I don’t want to suggest that Southern California boosterism was anything that Frank Brown invented, or that media celebration of Redlands was more hyperbolic that it was around booms elsewhere in the region.

But coming back to water, and the way it relates to money and the disparate fortunes of places like Redlands and Moreno Valley, it behooves us to ask what happened next to high-flying Brown and Judson, and how that would shape both water right on the upper Santa Ana and the built environment of parts of the Inland Empire.

By the late 1880s, a restless Frank Brown, now in his mid-30s, was obsessed with expanding what he had done in Redlands. He had, I think, a gambler’s heart—and was addicted to the idea of buying dry land cheap, selling the dream, taking the cash, and then, in the vice grip of investors’ expectations of returns, designing the engineering features necessary to convey water to the acreage.

Going for Broke

If Redlands was his making, the twin colonies Alessandro (what would later become Moreno Valley) and Perris were his downfall.

Buying out the Bear Valley Land and Water Company, whose shareholders were not interested in expanding beyond Redlands, Brown and Judson reorganized as Bear Valley Investment Company (BVIC). They embarked on an audacious new scheme, purchasing 38,000 acres south of San Timoteo badlands, and issued four million dollars of stock in the BVIC as an initial offering. The idea was to sell the stock to investors in Chicago, East Coast markets, London, Glasgow, and Geneva. Meanwhile, the BVIC would sell land lots to potential settlers in Southern California with promises of water delivery to two bone-dry adjoining valleys where they had laid out prospectors’ stakes and instructed prospective settlers to imagine two romantic garden towns: Alessandro and Perris.

To do this, they calculated that they would need to double height of the bear Valley Dam, which would expand the capacity of the high-altitude reservoir from 20,000 acre-feet to 100,000—or so thought Frank Brown.

But here’s the thing—a deal like this is tough. Four million dollars was over ten times the amount of cash they had raised for the dam that made Redlands. And the point of the initial offering of the stock on the BVIC was not to utilize the profits from stock sales to pay workers and suppliers, but instead to the churn the stock in order to pump the price of the security, thus generating more profit for the BVIC majority shareholders.

Meanwhile, in the new, as-yet unirrigated colonies, Judson and Brown offered options on land that involved only a minimal down payment. Buyers could put three dollars down at auction, and pay 12 dollars on possession, and carry a debt for properties valued at 500 to 600 dollars. The land sales helped pump the price of the securities, and the securities sales primed the sales of land.

Then, to speed up the building of the dam and the complex conveyance system, the landowners in the new colony were encouraged to form an irrigation district under the Wright Act. After doing so, the district issued bonds in the amount of 765 thousand dollars to raise money for the water conveyance. By this point, with lots being bought up by speculators taking advantage of the easy terms, the water rates to pay for the bonds would be shouldered by fewer than 100 settled families on lands in Alessandro.

Perris, meanwhile, took a vote among 83 people to issue bonds in the amount of 442 thousand dollars.

It was a lot of moving parts, and a staggering amount of debt. The cash coming in the form of stock sales that should have gone to pay the contractors and suppliers and workers who were building the dam extension and conveyance instead was going back to stockholder in dividends in hopes that the return of cash would prompt the stock price to rise.

Contractors and suppliers, meanwhile, were being paid in paper—shares in the BVIC, in the Alessandro Land Company, and even the bonds issued by the newly-organized irrigation districts.

It was a spectacular churning of cash—absurd in retrospect, possibly—but maybe no more so than the sub-prime mortgage crisis that seized the very same region in 2008-09. (Perversely, Moreno Valley was the worst affected zip code in the U.S. in that financial crisis. In an echo of the 1893 crash of Alessandro and Perris, investors in New York and Europe were sure that California real estate was a sure bet, even though many of the mortgages being issued in California’s Inland Empire were interest-only loans, and were taken out in many cases by borrowers with no demonstrable income and no collateral.)

Ultimately, what doomed the venture, and kept Frank Brown from pulling off another Hail Mary pass—churning credit until he could deliver the water and sell paradise at high prices– was simply multi-year drought.

The naysayers were right— Frank Brown could build a conveyance system, but he couldn’t make rain.

Yearly precipitation, scant in 1891 and 1892, was near nothing in the winter of 1893-94. The reservoir at Bear Valley dwindled to half its previous levels. By the late 1890s, it was a dry lake. What existed in the Santa Ana system went to Class A water certificate holders in Redlands, not Class B certificate holders in Alessandro and Perris.

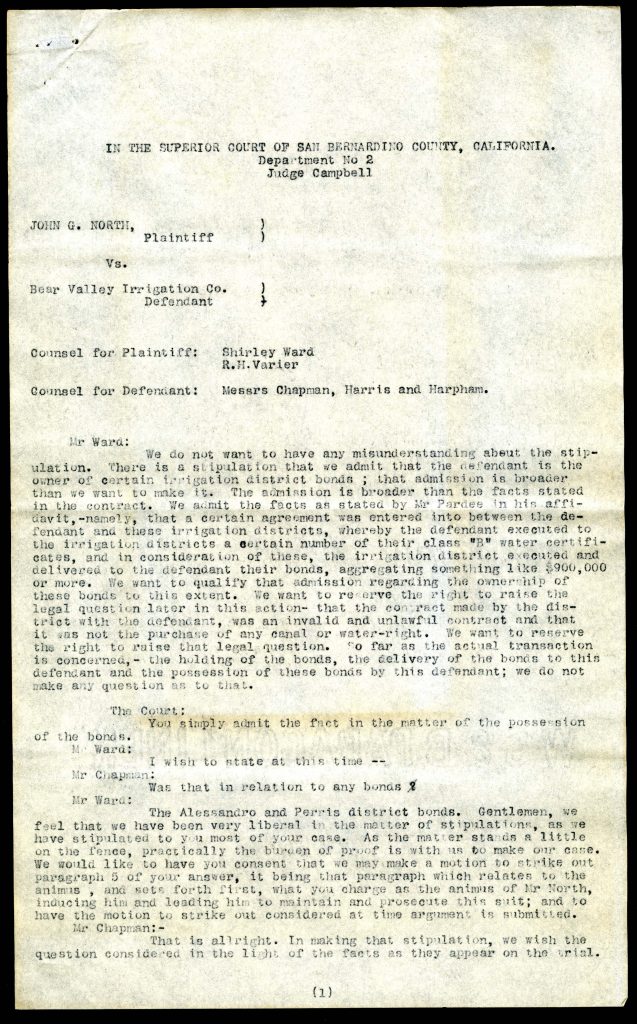

What ensued at that point was the absolute ruin of Frank Brown in the one of the longest, most complicated pieces of litigation in California’s history up to that date. It would take about a generation to settle all the claims.

In the aftermath, Redlands kept its long-term water rights while the concrete canals to Alessandro and Perris remained dry and disintegrated in the sun. When the rains began to fall again, the settlers at Alessandro and Perris had long abandoned their parcels, and their irrigation districts remained hopelessly in arrears to bondholders and angry contractors and suppliers.

With this abridged account, I mean to underscore several arguments:

First, water may be gold in California in the sense that it is scarce in relation to demand. But it also turns out that unlike gold, water is a poor medium exchange. Whereas market players seeking to buy and sell things with water as the underlying asset, they must do so by assuming that water in a stream or reservoir, like gold, will always be there in the same form. Nature, though, doesn’t cooperate. Sometimes water doesn’t fall from the sky. While people are often quite capable of adapting to droughts if they live directly from the land, they are often in dire straits when their relationship to the land is mediated through an abstract relationship to water through fixed water rights, or even worse, through water-backed securities or scrip. The Frank Browns of the region were bound to give way to a water state because their private sector schemes simply were incompatible with the vagaries of year-to-year fluctuation in water.

Second, the built environment of Southern California carries a history of 19th speculation in land and water, in railroad fare wars and 1880s dream-selling. Especially in the Inland Empire, anywhere you spot an oasis of mature trees shading broad avenues and stately homes, you can almost bet that the water rights that keep that shade in place were developed in this frantic era of irrigation, boosterism, and subdivision.

Third, the economic disparities between cities with greenscapes and hardscapes is more than a reflection of inequality, it is a driver of inequality in terms of the types of jobs that are created, and the quality of life and health that emanate from those distinct local economies. The fact that the residents of Redlands enjoy a distinctly different quality of life, governance, and health conditions from Moreno Valley is a fact tied to the systems we made with water rights.

[1] Ironically, Helen Hunt Jackson, an early activist and defender of California tribes, wrote the best-selling novel Ramona about the doomed love affair of a Spanish-speaking woman (Ramona) and a Native Californian man (Alessandro) in early Anglo California to raise consciousness about the political crisis of Native Californians. The mostly white reading public who devoured the novel and obsessed over the idea of “Ramona country” ignored the political content of the novel.

[2] William Hammond Hall made note of Brown’s speculative ideas about a Bear Valley impoundment in his authoritative survey on irrigation for the State of California. William Hammond Hall, Irrigation in California [southern] The Field, Water-Supply, and Works, Organization and Operation in San Diego, San Bernardino, and Los Angeles Counties. The Second Part of the Report of the State Engineer of California on Irrigation and the Irrigation Question. Sacramento: Office of the State Engineer, 1888.