4 Payahǖǖnadǖ Water Story

Teri Red Owl

This is our water story of Payahǖǖnadǖ, our homelands. We interpret the name as being the place where water has always flowed or the land of the flowing water. I’m going to talk about our water history or land history in our contemporary issues and will do so by a discussion of the mission and work of the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission.[1]

The Commission was established in 1991 and it is charted under the authority of the Bishop Paiute Tribe, the Big Pine Paiute Tribe and the Lone Pine Paiute Paiute/Shoshone Tribe. We have six Board of Directors, two from each tribe that are either appointed or elected. I am serving as the Commission’s Executive Director. Our primary task as a water commission is to be the planning and coordinating body protecting water rights for our member tribes. We also provide other services such as agricultural and environmental other water related services, as well as provide environmental education. We even serve tribes outside of our immediate geographic area and provide services throughout California, Arizona and Nevada.

This map indicates our location: These lands constitute our homelands, located about 270 miles north of Los Angeles, and about 200 miles south of Reno, Nevada. We are Paiute people and we call ourselves Nüümü. We are water people and believe that we were put in this place, this location by the Creator to take care of the water and to respect it. It means life to us and to everything.

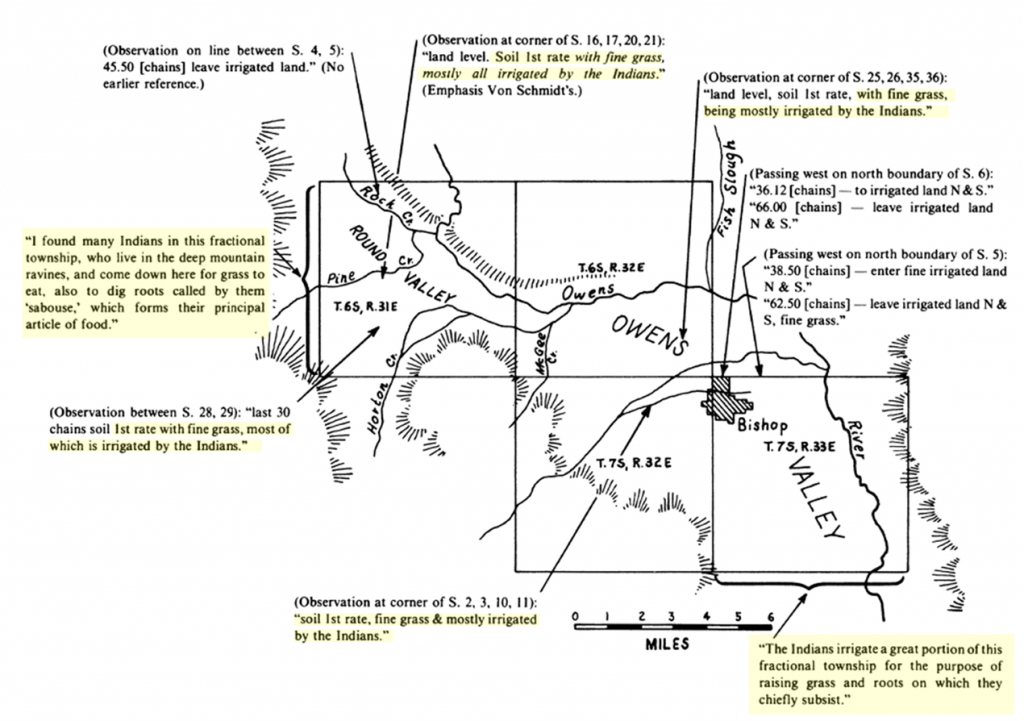

As it did for millennia prior to the arrival of white settlers in our homelands, which began in about 1850s, we irrigated pretty much the whole valley. We had irrigation networks that were hand dug that included 60 miles of ditches and covered a considerable area. These networks typically contained a dam and a ditch per plot of land. As Fig. 2 illustrates, we were supplying water to irrigate our crops, ditches that diverted water from one of the main creeks flowing from the mountains. Our main crop was a grass—tüpüsi/taboose—and these were the little tubers that we would eat. Given their small size, we had to manage fields and fields and fields of taboose to sustain ourselves.

To manage the water, each year the Paiute people would elect a tuvaijü, the head irrigator. This person would assess the land and decide where to spread the water that year. They then would dig these ditches and these waterways by hand; we did not have shovels but instead used what was called a pavodo, which was an eight-foot-long hardwood pole, approximately four inches in diameter. The men would get together and dig the ditches that would be used to spread the water. As part of their conservation strategy, we would alternate the areas that would be irrigated, a process that allowed previous worked land to recover. We knew how to take care of the land.

We also knew how to respect the water, to move it to where we needed it and to ensure that it eventually flowed back into its natural waterway. This Indigenous system of land-and-water management was the subject A. M. von Schmidt’s 1855-56 survey of the Owens Valley for the federal government. As part of his report for the state, he created this map which shows the irrigated areas and his revealing comment: “I found Indians in the fractional Township, who lived deep in the mountain ravines, they come down here for grass to eat and also dig roots, by them called Taboose actually, and that’s a principal article of food.” He talks about the soil being first rate with fine grasses and noted that large areas of the valley were being irrigated.

In 1859 Capt. J.W. Davidson explored throughout the valley and his insights about our life in Payahuunadü are noteworthy:

They have already some idea of tilling the ground, as the acequias which they have made with the labor of their rude hands for miles in extent, and the care they bestow on their fields of grass-nuts, abundantly show. Wherever the water touches this soil of disintegrated granite, it acts like the wand of an Enchanter, and it may with truth be said that these Indians have made some portions of their Country, which otherwise were desert, to bloom and blossom as a rose.

That is just a really precious description that I hold dear to my heart because I can only imagine what it took to make the land look like that.

White Settler Colonialism

In the 1850s, white settlers and cattle ranchers moved into the valley and pushed us off the land in 1863. This despite what Capt. Davis had said just four years earlier: “I repeated to them…that I had reason to believe that their Country was set apart by the Government—exempt from settlement—for their use so long as they maintained honest and peaceful habits.” Colonel Warren Wasson reiterated Davis’ perspective: “They have been repeatedly told by officers of the government that they should have exclusive possession of these lands, and they are now fighting obtain that possession.” White miners, ranchers, and others disrupted these promises. Noted one Indian agent: “Owing to recent and extensive mines discovered in the Owens River valley, and the consequent rush of miners and settlers there, I deem that locality for an Indian reservation entirely impractical.”

Yet over 900 of my people were eventually forcibly marched by the United States cavalry out of our valley to Fort Tejon, in present-day Tejon Pass, which is north of Los Angeles and south of Bakersfield, California. There was a lot of people who were killed along the way, and we have extensive information about the massacres that took place down at the southern end of our Valley at a lake area that we call Patsiata, now known as the Owens Lake.

Eventually, we came back to the valley, or those who survived the forced march and subsequent imprisonment—and escaped—did. What we found is that the areas that we had been using were completely overrun by the farmers and the ranchers who started growing their commercial crops—corn, wheat, and alfalfa. Because they had stolen the rich soils of our homeland, we moved to the sites, we began to make homes in the areas we once lived on and became day laborers for the white settlers’ farms and ranches. And at that point in time we really were a prime, indispensable labor source for these ranches in the valley and we actually developed a good relationship and created our new norm of existing in our homelands.

Los Angeles’ Water Schemes

Then this situation changed once again. Why did this change? Because Los Angeles and its agents first came into the area in the 1890s, and as they bought up land our Valley, Payahǖǖnadǖ, became the watershed that for more than a century has supplied Los Angeles with the majority of its drinking water through the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

In 1906, voters in the city of Los Angeles approved plans for the Los Angeles Aqueduct that included purchasing land and water rights in Payahuunadü. The aqueduct was completed in 1913 and Los Angeles began exporting water. The city had already been purchasing ranches and farms, and their owners were willing to sell because they no longer had a guarantee of water. The water was being channeled south along the 233-mile aqueduct. By 1933, Los Angeles had purchased about 85% of the valley’s residential and commercial properties and owned 95% of the valley’s farm and ranch land. In 1941, the city had extended its control north to Mono Lake and began to export water from the Mono Basin. A second Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed in 1970, and the combined capacity of the two is 780 CFS (cubic feet per second) or 570,000 acre-feet of water per year, an extreme amount of water.

The aqueduct’s impact on our people was tied to the rapid decline in farming and ranching operations. We lost our jobs and we were no longer able to take care of themselves. Worse yet, the city of Los Angeles, through the Department of Water and Power, worked hard to dislodge us from what lands we still lived on to facilitate getting water to Los Angeles. They succeeded. Today, we live on tiny, tiny reservations that combined only total just over 1700 acres of land. This is compared to our historic territories that encompassed the entire Owens Valley, about 460,000 acres of land. It is really hard for our people with the populations that we have to survive on that small land base.

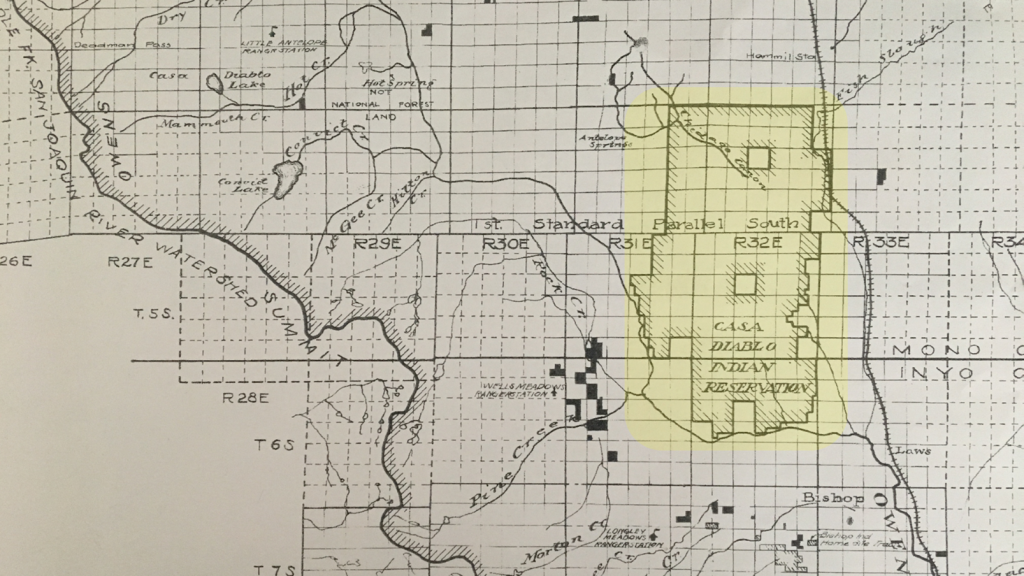

To understand how this happened to my people, let’s go back to 1912 when President William Howard Taft set aside a reservation of 2800 scattered acres, along with an additional 67,000-acre tract of land put in trust for the tribes; the large tract was to have become the Casa Diablo Reservation—but it never materialized. The Indian Service was supposed to figure out how to get water to these table lands, because there are no streams that flowing through there. It was their job to figure out how can we get water from these different lakes and reservoirs to this area, but they did not do it.

Instead, in 1930, Los Angeles produced a report that said those lands were “non-operative waste land” and they should be removed from trust status and made public domain. The LADWP argued that we were squatters and that we were wasting water, and that the best solution was either to relocate us or remove us from the valley.

The reason the city argued this point is that it wanted to secure those lands as a watershed protection for the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Within two days of Secretary of Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur sending the City’s report to and advising President Herbert Hoover to remove these lands from trust status, the president did so in Executive Order 5843, which revoked President Taft’s 1912 Executive Order that had established these trust lands. We were never able to convert those lands into reservation lands.

At the same time, Los Angeles was buying up individual allotment lands that Indians owned in the valley. By 1933, the city had bought 78% of the allotment lands in Owens Valley, adding more than 4,400 acres to its control of the region’s land and water rights. As part of that process, and three years earlier, the Department of Water and Power published a report called the “Indian Problem.” Have taken away lands that had been set aside in trust, bought out allotments for pennies on the dollar, the city report described the Indians as “homeless,” we were “squatting,” and we were making “waste of water.” We were doing what we knew how to do, living near water and taking care of it.

The city proposed a couple of solutions—to relocate us or to remove us from the valley. “By grouping in Indians of Owens Valley on the various sites spoken of there would be possible better control.” This would solve, from the city’s perspective, the “question of land acquirement and title definition fixed unquestionably. There is no question but that the Indian would react favorably and along progressive lines and eventually become self-supportive to a large degree.”

Based on that report and with the goal of centralizing us and controlling us, the United States government and the City of Los Angeles entered into a land exchange that met both governments’ needs. The United States had prior to that exchange had purchased private lands that were scattered here and there for the use of the indigenous people, and they were having to supply water to those areas, and in some cases it took a lot of water to get it to the place of use. Los Angeles characterized this as wasting the water that it wanted.

In 1937, Congress authorized a land exchange with the city without ever consulting us. The legislation was passed very quickly. On March 3, 1937, the bill was introduced that authorized a land exchange between the City of Los Angeles and the Department of the Interior (PL 75-43) which resulted in the establishment of a land-base for the Bishop, Big Pine, and Lone Pine Reservations. It passed on March 10 of that year When that happened, essentially the United States gave up almost 11,000 acre-feet of water in exchange for the delivery of just over 5,500 acre-feet of water. We also lost the riparian rights and we do not have groundwater rights under our existing reservations. we didn’t have a voice in what happened, we didn’t have a say.

Water Prospects

This untenable situation led the tribes to form the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission in 1991 and three years later the Department of the Interior appointed a Federal Fact-Finding Team, which concluded that the Bishop, Big Pine and Lone Pine Tribes had a valid claim to the water rights associated with the 1937 Land Exchange. We were not receiving all the water we were entitled to on our current reservations and that groundwater pumping by Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) adjacent to our lands was causing the groundwater beneath the land to intermittently or permanently decline.

The Fact-Finding Team also concluded that the earlier Land Exchange proved to be unfair to the Indians for a variety of reasons. Including: “…the value of the Indian lands exchanged to Los Angeles exceeded the value of the lands Los Angeles traded to the Indians…”; the exchange “operated as an effective temporary extinguishments of the Indians’ ground water rights underlying the Indians’ traded lands…”; and if “Los Angeles is pumping water underlying the Indian offered lands, or if Los Angeles is pumping water to the Indian offered lands that results in the depletion of the water underlying the Indian offered lands, Los Angeles is in violation of its agreements with the United States and is converting to its own use, without legal authority, the property of the United States.”

During that same year the Tribes, through the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission and Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), contracted with Natural Resources Consulting Engineers, Inc. (NRCE) to perform an Indian reserved water rights (Winters Rights) quantification study for the exchanged lands of the Owens Valley Indians. The study was performed using the Practicably Irrigable Acreage (PIA) concept. This concept takes into account the historic, present and future needs of the Tribes based on consideration of the land base for irrigation and other uses, water supply from both groundwater and surface water, the climate of the area relative to the adaptability of various crops in the region, costs of facilities to serve water for both agricultural and non-agricultural water demands, and the economic returns to justify the claims of water.

In July 1995, a Federal Water Rights Negotiation Team was appointed by the United States Department of the Interior to facilitate negotiations on the quantified water rights for the Bishop, Big Pine, and Lone Pine Tribes. Two years later, the team negotiated an Owens Valley water rights agreement with the LADWP. The agreement is commonly referred to as the 1997 Principles of Agreement. It was not ratified by all of the Tribes because it lacked access to “wet” water, infrastructure funding, land acquisition, and the usual benefits found in water settlements. The agreement was essentially a “paper” water right and would put new restrictions on the existing water the Tribes were utilizing. The Negotiation Team was unsuccessful in assisting the Tribes with reaching an acceptable settlement of water rights. It appeared that the negotiators were doing their best to see that the Tribes received as little as possible. The Department of the Interior declined to address numerous questions and concerns about the proposed settlement that the Tribal governing bodies raised. Because the Tribes would not ratify an agreement that was not in their best interest, the federal government withdrew its support. With the dissolution of the negotiation team, the negotiations came to a standstill.

As a result of a process established by the federal government including the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the lack of on-going support in the negotiations, disagreements concerning beneficiaries appurtenant to the 1937 Land Exchange arose. Consequently, the Fort Independence Reservation and the Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute Tribe withdrew their membership from the Commission in 1999 and did not participate in any future collective water rights negotiations. Despite the manipulation that created division amongst the Tribes in the Owens Valley and Eastern Sierra, the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission continues to work with environmental staff from all the Tribes including the Fort Independence Reservation and the Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute Tribe on environmental protection.

The Tribes recognize their common goals of healthy communities and environments. The Tribes understand that the LADWP and federal government strategy of divide and conquer has enabled them to defer and deflect responsibility and has been the primary barrier to negotiation and settlement of issues related to the 1939 Land Exchange. The Tribes believe that the era of divide and conquer is over. We’re not giving up. Not only are we seeking the return of land and water. We’re also fighting to save our homelands.

[1] Teri Red Owl would like to acknowledge that some of the historical images were provided by Sophia Borgias, a researcher who works closely with the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission and some of the artwork was created by the Aqueduct Between Us project.