14 Analyzing the Effectiveness of Quotas for Women in Latin American Legislatures – Sydney Heath

Sydney Heath

Introduction

Gender quotas in national legislatures have become an increasingly popular method for expanding female political participation and furthering women’s rights across the world. Worldwide, the first gender quota in a national legislature was implemented in Argentina in 1991. These quotas generally take the form of candidate quotas, meaning that political parties must nominate a certain percentage of female candidates in elections. Legislative gender quotas have been particularly concentrated in Latin America and the Caribbean, although they are also popular in Scandinavian countries. In fact, of the 33 countries in the Latin American region, the only ones that do not currently have mandated gender quotas in some form in their legislatures are Belize, Cuba, Trinidad and Tobago, and Suriname (International Idea). This paper will attempt to determine the extent to which quotas for women in Latin American governments can be considered successful and will also consider what “success” means in this context. Specifically, must quotas lead to a greater number of policies that support women to be considered successful, or is their ability to increase female political representation enough?

This paper will begin by examining the existing literature on the importance of increasing women’s political participation both in Latin America and everywhere. It will then define and distinguish between two important terms: political representation as process and representation as outcome, in order to analyze the effectiveness of gender quotas in influencing policy changes. The next section will look specifically at Argentina as a case study to determine the effectiveness of quotas in increasing women’s political representation and in passing pro-women policies. This will be followed by an analysis of Amartya Sen’s (2000) definition of development as freedom to determine how we can define effectiveness for gender quotas. The final section will consist of an explanation of other factors that should be considered when thinking about the effectiveness of quotas.

The Importance of Women’s Political Participation in Latin America

In the 2012 annual report on gender equality published by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the authors touch on the importance of women’s political participation and representation in Latin America. They discuss both the extensive improvements that have been made in this area over the last decade while also acknowledging that there is still substantial work to be done: “Women’s participation in politics has altered the democratic landscape, but those who reach the highest levels as political representatives are still running up against glass ceilings or cultural and financial barriers that hinder them from playing their political role as citizens with greater independence and with a greater endowment of resources”(ECLAC 2012, 9). The authors’ focus on autonomy is particularly relevant to the topic of the inclusion of women in government positions. Autonomy of decision-making for women describes the presence of women in executive, legislative and judicial roles where they are able to influence policy (Bárcena 2012, 24). According to a number of scholars, including the authors of the ECLAC report and a UN Women report on inclusive representation in Latin America and the Caribbean, decision-making autonomy is especially important because the policies that female politicians influence often have a direct impact on other women, so it only makes sense for women to have the ability to be involved in the decision-making process (UN Women, 2021).

While the ability to influence pro-women policy is one reason to prioritize women’s political representation, there are other scholars such as Amartya Sen whose works would lead us to believe that gender parity should be a goal in and of itself, regardless of whether or not it leads to an increase in pro-women policies. Afterall, women make up approximately 50 percent of the world’s population, and so legislatures should represent that ratio. Sen views freedoms such as political participation and the ability to participate in the decision-making process as essential parts of the very definition of development, regardless of whether or not those freedoms lead to other improvements such as an increased GDP, or in this specific case, pro-women policies (Sen, 1999). This paper will explore both of these perspectives on the relative success of legislative quotas and ultimately determine which is more useful.

Different Perspectives on Representation

When determining how to analyze the effectiveness of quotas for women, two researchers named Jennifer Piscopo and Susan Franceschet have come up with an important distinction between “representation as process” and “representation as outcome”. Before their contributions, researchers focused mainly on whether or not a greater number of female legislators led to the passage of an increased number of pro-women policies. Piscopo and Franceschet, on the other hand, make the distinction between “representation as process”, which they defined as female legislators’ ability to affect the legislative agenda (i.e. propose more pro-women bills), and “representation as outcome”, which they define as female legislators’ ability to successfully pass pro-women laws (Piscopo and Franceschet, 2008). These terms are critical to analyzing the success of quotas for women in Latin American legislatures.

Quotas’ Effect on Percentage of Women in Legislatures

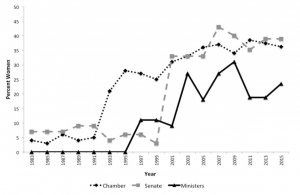

One way to determine whether or not quotas have been effective is to determine whether they have successfully increased the percentage of female legislators in the Latin American countries in which they have been implemented. In Argentina, quotas for women were first put into effect in 1991, mandating that political parties nominate 30 percent female candidates. The graph below shows how the percentage of female legislators in the lower house increased from around 5 percent in 1991 to around 35 percent by 2015 (Barnes and Jones, 2018). Most recent data shows that that number has increased to 39 percent as of 2019.

Figure 1: Percentage of Argentina’s Women in the National Parliament and Executive Cabinet by Year (Barnes and Jones, 2018).

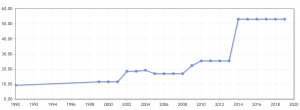

Bolivia has seen similar success with its quotas for women. In 2010, the Bolivian government passed a law mandating that 50 percent of legislative candidates be women. Figure 2 below demonstrates the significant increase in the percentage of women in the legislature since 2010 as a result of these quotas. In 2019, the percentage had reached 53 percent, surpassing the goal of parity.

Figure 2: Percentage of Female Legislators in the Bolivian Congress from 1990 to 2019 (Index Mundi)

While the quotas for female candidates in Latin America have generally increased the percentage of female legislators, there is still much work to be done. Currently, only two of the 33 Latin American and Caribbean countries have female presidents, and 70 percent of Latin American countries have lower houses of their legislative branches that are less than 40 percent women (Capurro 2021). Belize comes in at the bottom of this list with only 12.5 percent women while Cuba’s lower chamber has the highest proportion of women (53.4 percent) (Bloomberg 2021). These low percentages exist in spite of the fact that most of the countries have policies that mandate gender quotas of between 30 and 50 percent for legislative bodies.

In 1997, Brazil’s government passed a law that created a gender quota for political parties, meaning that they had to reserve 30 percent of their ballots for women. Despite this quota, women currently make up only 15 percent of Congress (Bloomberg, 2021). One of the reasons for this discrepancy is that political parties can nominate both a male and a female candidate for a single seat and they tend to put their support behind the male candidate (The Economist 2018). In Chile, political parties receive extra funding for each female politician elected, and yet women have received significantly less funding from political parties (Bloomberg 2021). There are a number of other ways that male political candidates have ended up taking the place of female candidates. In Bolivia in 1999, male candidates used the female version of their names on ballots (The Economist 2018). In Mexico in 2002, right after the gender quotas were first introduced, political parties would run female candidates in districts they knew they would not win; later when laws prevented this from happening, female politicians would step down right after being elected to allow male politicians to take their places (The Economist 2018). Since 2014, this particular loophole is no longer an issue in Mexico because a constitutional amendment prevents men from replacing female politicians who resign (The Economist 2018). Figure 3 below shows how a number of countries in Latin America with quotas are not even close to meeting their mandated candidate quotas (The Economist 2018). While there is significant room for improvement, quotas have increased the number of female lawmakers overall.

Figure 3

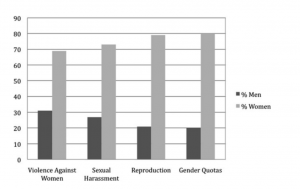

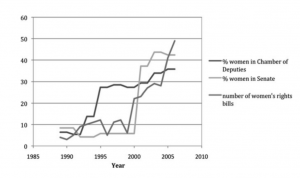

Case Study: Argentina

This section of the paper will consider the effects of gender quotas on pro-women policy. It will focus specifically on Argentina, the first country in the world to implement legislative gender quotas in 1991, to determine the effects of gender quotas on representation as process and representation as outcome respectively. Since Argentina’s quotas have been in place for the longest amount of time, it is the most logical country to analyze when looking at the effects of quotas on policy. Figure 4 below shows the percentage of bills focusing on gender-related issues that were introduced by female legislators in Argentina between 1989 and 2007. On all four of these topics (Violence Against Women, Sexual Harassment, Reprouction and Gender quotas), the percentage of female legislators that introduced these bills is significantly higher than the percentage of male law makers. Figure 5 shows the number of women’s rights bills introduced by year in Argentina. As the number of female legislators increased in both the upper and lower houses, the number of pro-women bills also increased. From both of these graphs, it is clear that increasing the number of female legislators has a direct impact on the legislative agenda (i.e representation as process, as defined by Piscopo and Franceschet). Other countries have seen similar trends. In Mexico from 1997 to 2009, female legislators were six times more likely than male legislators to propose legislation focusing on women’s rights or children’s rights (The Economist, 2018).

Figure 4: Percentage of Pro-Women Policies Introduced by Sex in Argentina between 1989 and 2007 (Piscopo and Franceschet, 2008).

Figure 5: Number of Women’s Rights Bills Introduced By Year in Argentina (Piscopo and Franceschet, 2008).

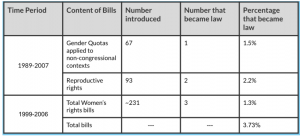

While it is certainly important to note the improvement in representation as process that has resulted from gender quota laws, it is representation as outcome that would in theory have lasting effects on the overall wellbeing of women. Piscopo and Franceshet also examine the effects of quotas in Argentina from this perspective. Figure 6 below shows that between 1989 and 2007, there were 160 bills focusing on gender quotas and reproductive rights that were introduced. Of those, only 3 became law. While it is true in general that a small percentage of all bills proposed in the Argentine legislature become law (only 3.73 percent), that is still more than two times larger than the 1.3 percent of all women’s rights bills that become law. Based on this data from Argentina, increasing the number of female legislators has not yet had an impact on the number of pro-women bills that become law (i.e. representation as outcome).

Figure 6

How Can We Define Quota Success?

Despite the fact that gender quotas have seemed to have little impact on the passage of women’s rights laws, I argue that they have intrinsic value simply because they increase the political representation of women, which is important in and of itself. Much of the previous literature on quotas for women in politics has been concerned with the specific policies that female legislators help pass, and whether or not they take women’s interests into account. Of course, “women’s interests” is a broad term because women of different ethnicities and socio-economic levels have vastly different life experiences and interests, which is explained partly through Crenshaw’s idea of intersectionality (1991). In the words of authors Susan Franceschet and Jennifer M. Piscopo in their analysis of quotas for women in Argentina: “the idea that female politicians are needed to represent women’s interests assumes a homogeneity among women that reinforces essentialist notions of an exogenously given, universally shared, fixed female identity”(Franceschet and Piscopo 2008, 396). Additionally, women of different political leanings will have different definitions of “pro-women policies”. Studies have shown that electing left-leaning officials into government rather than focusing on electing women is more likely to lead to laws that further women’s rights issues such as abortion, domestic violence, and childcare (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008, 399). That being said, one specific study by Susan Carroll in 2001 found that women from right-leaning parties did tend to be more liberal on issues of gender than men in the same parties (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008, 399).

Taking into consideration both the research done on the effects of female policy makers along with Sen’s definition of development as freedom begs the question: Do quotas need to lead to pro-women policies in order to be considered effective? All women, regardless of the policies they are able to pass, should be given the opportunity to be involved in politics, according to Sen’s beliefs about freedoms. Empowering women through increasing their political participation should be a goal in and of itself and not just a means to an end. Although Sen writes about the more general topic of development, his ideas on this issue are still quite relevant. He writes:

“These substantive freedoms (that is, the liberty of political participation or the opportunity to receive basic education or health care) are among the constituent components of development. Their relevance for development does not have to be freshly established through their indirect contribution to the growth of GNP or to the promotion of industrialization”(Sen 1999, 30).

In other words, regardless of whether or not a freedom like political participation leads to other benefits for women and society, it is still an important goal to pursue. When considering whether quotas have been effective, it is, of course, interesting to look at the specific effects that female politicians have had on the political agendas and the policies being passed. However, what is most important is the simple question of whether or not quotas have effectively increased the number of women in political positions in Latin America. While there have been some setbacks when quotas were first implemented in Latin America as was previously detailed in this paper, every country with a legislative quota for female candidates and legislators has led to an increase in the number of women in politics. While many countries have not in fact met their goals due to loopholes in the quota laws, there has still been significant improvement that has potential to further increase political participation for women once the loopholes are further considered and prevented.

Other Factors Affecting the Success of Gender Quotas

There are two other factors that affect the success of gender quotas that must be considered: perceptions of “quota women” and the importance of an intersectional approach to political representation. “Quota women” are women who are elected in countries with gender quotas). The way these women are viewed by society is an important part of the picture that may influence whether or not women in countries with quotas even want to run for office. According to Franceschet and Piscopo: “quotas also generated a perception that “quota women ” needed special treatment (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008, 395). Franceschet and Piscopo also write that: “quotas contribute to the perception that female representatives are needed because of their distinctly feminine perspective”(Franceschet and Piscopo 2008, 402). There are potentially some female legislators who might react adversely to both this mandate and the perceptions of special treatment, leading them to actively avoid policies that support women specifically (Franceschet and Piscopo 2008, 402). In truth, female politicians tend to be as qualified as male politicians in Latin America, therefore the solution to the poor perceptions of quota women would likely need to be an educational campaign that would prevent misinformation on this issue.

The other factor to consider is related to the concept of intersectionality. The idea of intersectionality is a term coined by Kimberly Crenshaw that refers to the distinct forms of oppression that intersections of different identities experience (Crenshaw 1991). Crenshaw explains that Black women, for example, face oppression not only because they are women but also because they are black, and so it is important to consider how their experiences may differ from those of White women or Black men (Crenshaw 1991). The UN Women report relates the concept of intersectionality to the need for quotas not only for women in government but also for other disadvantaged groups like Indigenous women. The report explains that although there has been a significant increase in the percentage of women in government positions in Latin America, the majority of these women are not Indigenous, and this is an issue that needs to be addressed. A number of countries like Colombia, Bolivia, Mexico and Venezuela have quotas for Indigenous people in their legislatures, but they tend to be filled by men (UN WOMEN 2021).

Conclusion

This paper has analyzed the effects of legislative gender quota laws in Latin America and looked specifically at Argentina, the first country in the world to implement gender quota laws of this type. The analysis has shown that quotas have broadly increased political representation of women in the countries in which they have been implemented, and increasing the number of female lawmakers has influenced the legislative agenda. However, the number of women’s rights-focused bills that become law has not been significantly impacted. Using Amartya Sen’s work describing the intrinsic importance of freedoms such as the freedom to participate in politics for women, I have argued that gender quotas can be considered effective because they have successfully increased the number of female politicians in the Latin American countries in which they have been implemented, regardless of whether or not they influence the rest of society. There is substantial need for more research and work on other factors that affect the success of quotas, specifically the perception of female politicians in countries with gender quotas as well as the need for quotas that consider the intersectional experience of multiple identities.

Bibliography

Barnes, Tiffany D., and Mark P. Jones. “Women’s Representation in Argentine National and Subnational Governments.” Oxford Scholarship Online, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190851224.003.0007

Bolivia – Proportion of Seats Held by Women in National Parliaments (%), https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/bolivia/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. (2019, April 17). Observatorio de igualdad de género de América Latina y el Caribe (OIG). 2012 Annual Report: A look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women. https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/35445-gender-equality-observatory-latin-america-and-caribbean-annual-report-2012-look

Franceschet, S., & Piscopo, J. (2008). Gender Quotas and Women’s Substantive Representation: Lessons from Argentina. Politics & Gender, 4(3), 393-425. doi:10.1017/S1743923X08000342

Sen, Amartya. Development As Freedom. Anchor Books, 2000.

The Economist. 2018. Latin America has embraced quotas for female political candidates. (n.d.). https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2018/07/28/latin-america-has-embraced-quotas-for-female-political-candidates

UN WOMEN. 2021. Towards parity and inclusive participation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional overview and contributions to CSW65. (n.d.). https://lac.unwomen.org/en/digiteca/publicaciones/2021/02/panorama-regional-y-aportes-csw65

“Welcome to International IDEA.” International IDEA, https://www.idea.int/.