13 The Fight for Indigenous Female Leadership in Latin America

María Bedoya

Introduction

The intersection of various identities and conditions reproduces marginality for certain groups across generations. In order to address the issue of gender and political inclusion in Latin America, it is important to elevate and give a platform to those whose influence was most diminished by the colonial legacy. Indigenous women face systemic challenges to the full realization of their human rights. By organizing at local, national, and international levels, indigenous women engendered a novel movement with fluctuating measures of efficacy and structure within the region. Indigenous feminism, while not always presenting with this name, confronts multiple forms of discrimination against indigenous women such as violence, lack of access to education, and disproportionately high rates of poverty (UN Gender and Indigenous People, 2010). Gender equity and women’s political empowerment are fundamental steps to meeting sustainable development goals. Developments within the indigenous feminist movement merit consideration as they are a strong indicators of successful inclusion of marginalized groups overall.

Relevant Literature

In The Emergence of Indigenous Feminism in Latin America, author Aida Hernandez Castillo begins with a quote from Alma Lopez, an ex-council member of the City of Quetzaltenago, Guatemala who states that her organized community is not living in accordance with the philosophical principles of Mayan culture if it fails to recognize lived experiences from women other than herself. The source focuses on the factors that characterize this continental movement as independent and unique. Use of the term “indigenous feminism” provokes discord among the organized, which reveal how the movement calls to reexamine the importance of race and class in the process of identity formation for mobilized groups. Hernandez Castillo claims the individual voices of indigenous women can be found in the documents produced in meetings, workshops, essays, interviews, as well as academic publications, which emphasize the need to prioritize diversity and use it to recalibrate a more inclusive feminist practice. Indigenous feminists in Latin America have organized not only to demand political rights, but also to advocate for unity within because they believe the path to a more just society begins with the family itself. This source specifically references belief systems and values that shape the aspirations of indigenous female organizations. Hernandez Castillo explains that the battle for more just relations between men and women is based on definitions of personhood that transcend Western individualism as their definition of equality rests on the complementarity between genders as well as human beings and nature (p 540). Influence from the referenced relationship among living beings is one of several distinctions that separates this movement from urban feminism.

The author acknowledges the value of an alternative perspective offered by the continental movement, and while elevating the status of indigenous women is pivotal, it’s equally important to understand its organizational structure as it challenges academics to reconsider the parameters used to define feminism in the past. Indigenous feminism is not a conglomerate of social theories and political practices assigned to enact equity. Communal effort from women of diverse cultural backgrounds and experiences has brought about an untried approach to mobilizing, and it continues to evolve. It’s this aspect of singularity that affirms the relevance of intersectionality in social movements. Hernandez Castillo points out that indigenous women perceive urban middle-class feminism as alienating from their shared struggles with indigenous men, and within their communities feel unable to relate with men on unique experiences as women (p 542). Some indigenous feminist demands coincide with urban feminism, yet they are substantially distinct because of the economic and cultural context in which indigenous women constructed their gender identities which impacts conceptions of femininity and ways of building alliances. Such factors lead to the emergence of a new political identity as it stands separate from the political identity of the indigenous movement and separate from the gender identity of the feminist movement.

Similarly, author Audre Lorde argues that using patriarchal tools to examine the fruits of the patriarchy can only produce the most narrow perimeters of change. In her speech to NYU’s humanities institute, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master’s House, Lorde advocates for heightened consideration of input from women who are inadequately represented in the feminist movement. The predominance of urban, middle-class, white female voices in feminist movements is essentially a byproduct of patriarchal influence and only by elevating Black, lesbian, and Third World women can we achieve significant progress. Lorde introduces the concept of interdependency– the belief that differences are a necessary polarity– as a way to resist the extractive nature of previous inclusion efforts. Tolerance is not substantial for reform, instead, celebration and nurturance serve as conduits for creative function. Lorde engages women’s innate femininity and frames interdependency as a rejection of the view that difference is a cause for separation: “for women, the need and desire to nurture each other is not pathological but redemptive, and it is within that knowledge that our real power is rediscovered. It is this real connection which is so feared by a patriarchal world. Only within a patriarchal structure is maternity the only social power open to women.”

Applied Theoretical Framework

Indigenous populations in Latin America have historically been subjects of statistical invisibility which breached fundamental inadequacies in public policy design. During the creation of nation-states, indigenous peoples occupied a secondary position in the political sphere and the accumulation of inequalities affecting them carried over to the present day. Pioneers in consolidation include the indigenous Zapatistas of Mexico and their revolt in 1994; indigenous movements grew in strength during this period which preceded and eventually contributed to the region’s left turn (Rousseau & Ewig, p 427). Women in Latin America compose another marginalized group, although they made advances in political equity even earlier through the 1979 Women’s Convention whose impact prompted some Latin American states to revise their constitutions and incorporate the goals of gender equality as well eradication of sex-based discrimination (Deere & León, p 32). While both demographics became important political actors, a subgroup emerged whose needs were not parallel with either movement.

Since the 1990’s, indigenous women have taken an integral and vocal role on behalf of indigenous movements, yet they remain the most politically marginalized group in the region. Marginalization occurs not only through urban dominance in politics, but also often by the preeminence of male leadership within indigenous movements. Moreover, Latin American feminists historically have viewed indigenous women as beneficiaries of their cause rather than political partners (Rousseau & Ewig, p 427). While indigenous women’s experiences and demands vary significantly across and within countries, there is a transnational objective of maintaining unity with indigenous movements while creating new possibilities for them to assume political leadership. Collectively, indigenous women’s concerns focus on domestic and state violence, threats from extractive industries in the region, and the need for institutional guarantees for gender equality in decision-making. In framing their case for political empowerment, indigenous women face multiple forms of discrimination that overlap and are mutually reinforcing such as discrimination from their respective communities, high state institutions, and social heterogeneity (ECLAC 2020, p 40). Indigenous women embody a wide range of realities; because they are not a homogenous group, progress must reflect this internal diversity and their needs must be addressed from an intersectional perspective. While intersectionality was originally a tool to analyze the various ways in which race and gender interact (Crenshaw, 1991), it is now a useful lens to consider different intersections between gender as well as other social hierarchies such as ethnicity, social class, age, or territory. Their identities as both women and indigenous people not only exposes them to double discrimination, it materializes a particularly complex place at the intersection of both types of exclusion.

Indigenous feminism is novel in its organization and composition, this aspect of singularity affirms the considerable importance of intersectionality within social movements. Indigenous feminism does not fit among the parameters used to define feminism in the past because it is not a conglomerate of social theories derived from academic discourse. Historically, obtaining political empowerment for marginalized groups demands social movement mobilization. The groundwork paved by Latin American feminists could potentially serve indigenous women as a movement base, but the geographic, class, and race differences between rural indigenous women and the urban, middle-class, white or mestizo feminist movement leadership makes it uncommon for feminists to integrate the claims of indigenous women into their platform (Rousseau & Ewig, p 427). Furthermore, indigenous organizations often produce their indigenous authenticity by relying on strong notions of gender differentiation which perpetuate patriarchal gender ideologies. For the purpose of studying the political empowerment of indigenous women in Latin America, incorporating an intersectional analysis produces a more encompassing understanding of social movement’s internal dynamics and also distinguishes between social positionings and group identities. Social movements tend to consolidate collective identities and the social groups to which they relate to facilitate public understanding and legitimacy building (Rousseau & Hudon, p 10). At times this process has contradictory effects, such as invalidation of pro-life, religious feminists who diverge from the feminist movement’s predominant ideology. Social movements are created to address inequality and oppression, but more fundamentally they emerge from “cultural processes of meaning construction derived from social relations and material conditions” (Rousseau & Hudon, p 11). Intersectionality is the primary framework used to guide the analysis of internal processes within the indigenous feminist movement.

Case Studies

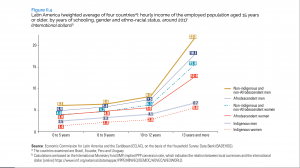

As a result of colonialism and its intergenerational impact, indigenous peoples of Latin America continue to face injustice and violence against their existence and territories. For the region as a whole, the dominating culture of privilege reflects the legacy of colonialism and slavery which consequently produces discriminatory social relations (ECLAC, 2020 p. 40). Historically, indigenous and Afrodescendent populations have been subject to statistical invisibility which infringes on public policy design since it disregards the specific needs of these “invisible” groups. Indigenous women’s omission from the discussion regarding ethno-racial inequalities not only exposes them to double discrimination, it places them at the intersection of both types of exclusion (ECLAC, 2020 p. 40). Despite the lack of sequential data from the region, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean sought to assess household surveys from 4 countries through an ethno-racial lens. A 2017 analysis of hourly labor incomes by ethnicity and race, and years of schooling concluded that indigenous women are significantly impacted by inequality and constitute the lowest rank on the income scale regardless of education level.

Table I

The intersection between gender, race, and indigeneity results in higher levels of material poverty and exclusion as a result of oppressive historical processes. Table I reveals a gap between the income levels of indigenous men and women despite both groups having the same level of education. While education is often considered the path to financial stability, gender factors in not only as an additional dimension but a form of inequality that intersects with other types of exclusion (ECLAC 2020, p. 41). Within Afrodescendent and indigenous populations, women have lesser financial autonomy than men. The unequal gender order as well as the structural challenges of exclusion create a systemic hierarchy demonstrated in the data; in descending order, men who are neither Afrodescendants nor indigenous earn the highest income, followed by Afrodescendent men, non-indigenous and non-Afrodescendent women, indigenous men, and lastly the most disadvantaged group composed of indigenous women.

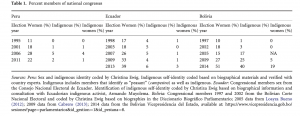

A 2017 source by Stephanie Rousseau and Christina Ewig provides an assessment of indigenous women’s political empowerment and determines whether pink tide governments of South America delivered on their promise of inclusion. The source compares the center-right government of Peru under Alan Garcia (2006-2011) and Ollanta Humala (2011-2016) with left-leaning governments of Rafael Correa of Ecuador (2007-2017) and Evo Morales of Bolivia (2006-2019). The late 1990’s in Latin America were characterized by support for left leaning government officials; eleven out of the eighteen democratic countries appointed left governments over the course of 15 years (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017 p. 425). This collective shift in the region confronted what scholars now call an “incorporation crisis”— market-focused policies imposed by right leaning governments who neglected the social and economic marginalization of certain groups. Examples of indigenous people’s unification, which preceded the region’s left turn, include the consolidation of Ecuador’s multiple indigenous groups into a confederation in 1986, and the Zapatistas of Mexico and their consequent revolt in 1994. Indigenous people’s mobilization resulted from the eradication of the corporatist arrangements of the 1980’s in which states granted a limited set of social rights to class-based groups; it was replaced by the pluralist arrangements of neoliberalism and influenced by democratization and the global discourse of “multiculturalism” (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017 p. 428). As subjects to multidimensional exclusion, indigenous women anticipated to gain the most from the pink tide governments’ promises of inclusion. The source analyzes whether Latin America’s pink tide prompted indigenous women’s political empowerment on the measures of constitutional citizenship rights, political inclusion in national parliaments, and state commitment through indigenous women’s policy machineries. For the purpose of this essay, we focus on the second measure, political inclusion of indigenous women determined by indigenous women’s presence in national congresses before and during the pink tide. The cases selected are similar in their extractive-based economies and vary in the strength of indigenous women’s organization within indigenous movements and their method of organizing. In regards to Peru, women organized primarily outside of mixed-sex indigenous organization and succeeded in obtaining some influence, but in the absence of a strong indigenous movement their power is limited. In Ecuador, women have organized principally within the indigenous movements, but have limited influence at the national level. Indigenous women in Bolivia, incorporated a novel aspect of gender parallelism as an organizational strategy—women-only organizations work alongside mixed-sex indigenous organizations to guide and promote indigenous women’s participation. Of the three cases, Bolivian indigenous women hold the strongest position within the indigenous movement (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017 p. 432). The authors argue that four factors are most likely to impact indigenous women’s political empowerment: the strength of national indigenous movements, a strong position of indigenous women within indigenous movements, the presence of a left governing party in support of the mobilization of indigenous voters, and the type of left party in office (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017 p. 427). Presence in national legislatures increased in all three countries during the region’s left turn, though only in the left cases of Ecuador and Bolivia did indigenous women attain representation that was proportional to indigenous population levels (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017 p. 438).

Table II

Table II reveals that indigenous women’s political inclusion increases as representation of indigenous people and inclusion of women increases. The chart illustrates an increase in legislative seats acquired by indigenous men as a result of electoral incorporation, but incorporation is delayed in achieving political inclusion for indigenous women. Peru is an exception as indigenous women entered the legislature earlier but presence declined over time. For Ecuador and Bolivia, the proportion of indigenous women in congress remains at or below level of women incorporated both before the pink tide and during the early pink tide years. Once gender parity is institutionalized, numbers rise. Indigenous women’s presence in national congresses is attributed partially to their leadership and organizing efforts, though also influenced by the gender parity laws passed in each of these countries during the region’s left turn.

Analysis

A range of deterrents work in unison to prevent proportional political inclusion of indigenous women in Latin America. Seemingly, the most direct and immediate resistance to indigenous women’s consolidation comes from their respective communities. While indigenous women face unique challenges separate from those of the community, there is a reluctance to address the gender dimensions of indigenous people’s practices because doing so is received as cultural interference or imposition of western values. Nonetheless, critical gender analysis is necessary from a poverty reduction perspective because it addresses gender-differentiated needs. As table 1 demonstrated, indigenous women occupy a secondary socioeconomic position to indigenous men despite completing the same levels of schooling. Bridging this financial gap could elevate indigenous women politically as they would gain wider access to resources and consequently enhance their organizational capabilities. Minimizing the influence of sociocultural impediments would advance the regional fight for indigenous female leadership.

Social movement mobilization is pivotal to the liberation of marginalized groups. Because of indigenous feminism’s fairly recent emergence, material support, guidance, and recognition on behalf of Latin American feminists could potentially steer the movement toward more perceptible, sustained progress. Generally, the geographic, racial, and class differentiations between both groups of women makes it unlikely for urban feminists to amplify the voices of indigenous women through their own platform, which is why the chapter advocates for intersectionality as the leading paradigm in the process of women’s development. In comparison, indigenous women have already been integrated– at different levels– into indigenous movements in Latin America. For this reason, the extent to which indigenous women can assume leadership positions within these movements is a strong indicator of their eventual political inclusion at national levels. Indigenous Bolivian women’s comparative success in political representation illustrated in table II can be partially attributed to the incorporation of gender-parallelism as an organizational strategy which functions in accordance with the indigenous notion of equality and complementarity introduced in the literature review section of this chapter. Bolivia’s quantitative success was also influenced by the type of party in power. Evo Morales’ MAS government is considered a “movement left” party, inspired by social movements who counseled and supervised political leaders, though the administration became increasingly populist in its final years (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017 p. 433). Thus, the party type in power and their relationship with social movements in the country are important factors behind indigenous women’s empowerment.

Conclusion

This chapter has analyzed the emergence of indigenous women as a new political subject in Latin America with particularly emphasis on movement structure and identity. While demands and presentations of indigenous feminism significantly vary across and within states, there is a transnational objective to elevate their socioeconomic status, assess patriarchal elements of indigenous customs, assume positions of leadership within their communities and at the national levels, and maintain unity with indigenous movements. Their indigeneity and gender not only exposes them to double discrimination, it subjects them to marginal exclusion from both the indigenous movement and the Latin American feminist movement. The chapter argues that partial incorporation of intersectionality and interdependency into feminists beliefs diminished the Latin American feminist movement’s potential for amplifying the voices of indigenous women. Furthermore, critical analysis of gender dimensions within indigenous practices is discouraged and perceived as a threat to indigenous communities’ autonomy and self-governance, which hinders indigenous women’s ability to advance female leadership. Overall, the chapter concludes that pink tide governments moderately delivered on their promise of inclusion for marginalized groups. In the cases of Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru, all three countries included constitutional guarantees for indigenous people’s rights and gender equality. On the measure of political inclusion, the left cases perform better, but the movement left party of Bolivia scores significantly higher due to the organizational structure of the movement and application of gender parallelism. It is important to recognize that our measures of political empowerment only communicate a fragment of the political life of indigenous women and a need remains for new literature further investigating inner workings of the movement.

References

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color” Stanford Law Review

ECLAC. 2020. “Women’s autonomy in changing economic scenarios” (pp. 13-45). UN/ECLAC XIV Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean

Hernández Castillo, R. Aída. 2010. “The Emergence of Indigenous Feminism in Latin America.” Signs, vol. 35, no. 3, The University of Chicago Press (pp. 539–47)

Lorde, Audre. 2007 [1984]. “The Master’s Tools will never Dismantle the Masters House” in

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde. Berkeley: Crossing Press

Rousseau Stéphanie and Christina Ewig. 2017. “Latin America’s Left-Turn and the Political Empowerment of Indigenous Women.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society

U.N, 2010. “Gender and Indigenous People” in UN Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues, UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues