8 Domestic Workers and Their Intersectional Struggle for Rights in Brazil- Sofia Guimaraes

Sofia Guimaraes

Introduction

When the topic is paid domestic work, the image that comes to the mind of many is that of a woman working as a maid in someone else’s home. Little attention is given to the question of what brought that woman to the situation she finds herself in right now, what life did that woman have before she settled for such a precarious job, and what identities does that woman carry with her? In Brazil, where domestic work is a very common form of employment for low-income women, these questions are of distinct importance because they lead to an interesting realization: Domestic workers are largely characterized as black low-income women.

In 2009 93% of domestic workers in Brazil were women, and 61,6% of these women were black[1]. Additionally, for every one hundred white women employed, twelve are domestic workers, while for every one hundred black women employed, twenty-one are domestic workers[2]. Needless to say, domestic workers are one of the most marginalized groups in Brazilian society, given that it is composed mostly by low-income women of color, a social group that historically has had little to no voice in political decision-making in the country. According to the UNDP, Brazil is among the countries in Latin America that most present obstacles to the political rights of women and to the political equality between men and women[3], ranking 9 out of the 11 countries. Women of color are at an even greater disadvantage as they are significantly behind white women, white men and black men in terms of elected politicians, barely accounting to 5% of mayors and councilors in 2016[4].

However, despite their lack of participation in the political sphere, domestic workers were able to mobilize in order to conquer several rights that they had been denied for decades. Starting in the mid 1900s, domestic workers recognized how as a group they embodied the intersectionality of race, gender and poverty, and began using their position in society to their advantage[5]. In this piece I aim, therefore, to examine how race, gender and class shaped the trajectory of the domestic workers’ social movement as they united forces, strengthened their labor union, and fought for their rights in the face of adversity in Brazil.

Key Concepts

An Overview of Care Work and How it is Perceived

Before examining domestic workers’ trajectory towards conquering their rights, it is important to understand what in fact it means to be a domestic worker, and this begins by recognizing how care work has long been undervalued, overlooked, and stigmatized by society. Even though giving and receiving care is central to human well-being, worldwide the responsibility of care is understood as women’s work and it is devalued in the eyes of the economic system, policies, and social norms[6]. Care work is recognized as all tasks that involve performing care in service of another person. The perspectives of care work are governed by the ongoing reconstitution of social relations of gender, care, and domestic service[7]. Housework and child care were traditionally treated as non-economic activities because they were often performed by housewives who did not receive wages, therefore even now despite the ‘liberation’ of many women across the globe, the feminization of care work continues to undermine it as ‘not really work’.

This devaluation is in turn reflected in how domestic workers are underpaid and their working conditions are depressed, which is especially concerning given the popularity of paid care work as a form of employment to low-income women. This form of labor can be brutal in that care-workers’ “emotional and physical care, their entitlement and rights and their human security are either disregarded or actively threatened, especially when their work is governed by the regulations of state-sponsored caregiver programmes.” [8]

Domestic Work in Latin America

Delving deeper into how domestic work is dealt with in low-income countries, Latin America serves as a perfect case study. Paid domestic work is an extremely common form of employment for low-income women in Latin America because of the nature of social inequality in the continent, which produces both the demand for domestic activities and a supply of inexpensive labor[9]. Given that Latin America is the region with the highest income inequality in the world it is not surprising that it also has the greatest prevalence of paid domestic labor (37% of the world’s domestic workers are in Latin America), formally defined as labor done within a residence[10]. These workers are overwhelmingly female, from racial and ethnic minorities, and low-income[11]. Therefore, the marginalization of domestic workers is highly intersectional because they do not earn less just because of their class but also due to their gender and because they are from a visible minority[12].

Indeed, about 15% of the urban female labor force in Latin America are employed as domestic workers and, even though employing these women as maids or nannies is a tradition dating back to the colonial and slavery era, governments are only now starting to recognize this form of labor as deserving of equal rights[13]. Domestic work in Latin America operated for years without formal recognition or labor rights and protections but by 2017 eight of the 18 Latin American countries had granted equal labor rights to the group[14].

It is also important to emphasize the importance of acknowledging the hardship that domestic work involves, as since it involves working within a household rather than a business setting, not much credit is given to the type of work and remuneration is extremely low[15]. For example, at the turn of the millennium, in Brazil, Mexico, Guatemala and Ecuador, the weekly hours of domestic work could extend up to 96 hours while workers in general were limited to 48 hours, very much because of the lack of recognition of domestic work as ‘real work’[16]. Moreover, UN data shows that the earnings of domestic workers were 41% of the average wage of the urban employed across the region[17]. The group began to gain rights by organizing and advocating for equal rights and respect but were met with challenges due to their precarious working conditions (long hours, their own family responsibilities, and little leisure time). Despite these challenges, many countries now have regulated domestic labor markets[18].

Intersectionality as a Tool for Social Movements

Of course, this analysis seeks to explore the specific method with which domestic workers mobilized in Brazil – using intersectionality to strengthen their movement – therefore, it is important to stress the relevance of this method in a wider scope. While the term intersectionality has its roots in Anglo-Saxon theorizing, the interplay of issues of race, class, ethnicity and gender have always been part of Latin American reality[19]. The term, therefore, can be used in the Latin American context to theorize gender in the multiethnic and class-divided structures and facilitate the process by which marginalized groups fight against oppression. Understanding this relationship is especially relevant when studying the mobilization of Latin American women against several forms of power in their daily lives, as it is by combining this collective identity – race, class, ethnicity, and gender – that they have conquered important political changes through social movements[20].

The general definition of social movements according to Jeff Goodwin and James M. Jasper is “conscious, concerted, and sustained efforts by ordinary people to change some aspect of their society by using extra-institutional means”[21]. It is important to pay attention to the “ordinary people” part of the definition because, as opposed to economic elites, ordinary people have no explicit formal means of achieving change rather than voting, and that is when social movements become a useful tool. As people become aware of a social problem they want solved, they can form some kind of movement to push for a solution because typical politicians rarely recognize new fears and desires without a mobilization from the public occurring first[22]. The first step usually involves the collective identity that organizers use to strengthen their loyalty to their cause, which is essentially what will drive the movement forward, and many times comes in the form of intersectionality[23]. Therefore, social movements are a central source of social transformation that often leads to innovation in values and political beliefs.

Where the Problem Lies

The Intersectional Aspect of Domestic Work in Brazil

In Brazil, 14.6% of employed women work in some sort of paid domestic work, compared to 1% of men[24]. This statistic shows how employment opportunities are limited to women because working in domestic work is rarely the first option, but rather an alternative when stable employment in the retail sector, for example, is not available[25]. Employers in the country are still heavily prejudiced against employing women even though they are more educated than men[26], which implies that the lack of employment alternatives for them is not a matter of qualification but rather of their gender. Domestic work offers precarious conditions, with little protection and regulation despite recent advances in legislation, therefore the disproportionate number of women in the sector represents the lack of good employment opportunities for women in Brazil.

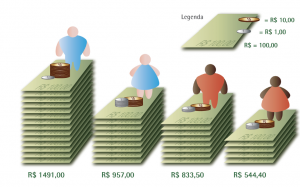

Going a step further and paying attention to the disparities based on ethnicity and gender in relation to employment, it is alarming to note that the lowest unemployment rate corresponds to white men, 5%, and the highest to black women, 12% [27]. These numbers reveal, therefore, the double burden that black women have on them: their gender and their race. Furthermore, 69.5% of employed women have at least 9 years of education, compared to 48.7% of black women[28], which can be associated to the fact that historically people of color in Brazil are of low income due to the tragic history of slavery and racial discrimination in the country. This, in turn, imposes a bigger burden on low-income women of color to leave the educational system and work to help sustain their families. The combination of racism and sexism present in Brazilian society poses an additional hardship on these women when attempting to be inserted into the workforce. Therefore, it is not surprising that out of all domestic workers, 63% are black women and that similarly, 18.6% of black employed women are domestic workers, compared to 10% of white women[29]. Due to lack of alternatives, black women disproportionately choose domestic work as a form of employment and in turn, are condemned to a life of no economic prosperity, little legal protection and poor working conditions more than any other social group[30] (figure 1).

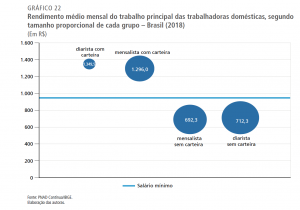

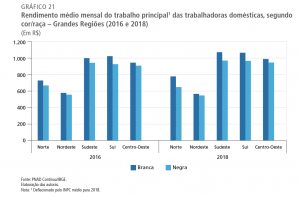

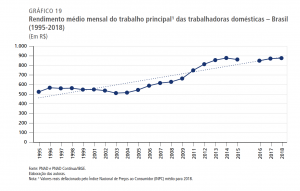

The poor working conditions that domestic workers endure are intrinsically linked to the informal nature of this form of employment. Due to the lack of rights of domestic workers in comparison to other workers, fiscalization, formalization and organization of this category of work is extremely hard[31]. Even though there have been advances in how many domestic workers have a formal work license – in 1995 the number was 17.8% and in 2015 30.4%[32] – the percentage still remains extremely low and the consequences are concerning as it implies most domestic workers earn below minimum wage (Figure 2). Without a formal work license, a domestic worker’s employer has no binding obligation to agree with working conditions such as established hours, wages, etc. Even more concerning is the fact that in 2015 29.3% of domestic black women had a formal work license, compared to 32.5% of white women[33] proving once again how black women are disproportionately negatively affected by the hardships of domestic work (Figure 3). On a more positive note, between 1995 and 2015 the average wage of domestic workers grew around 64% [34] largely because of the increase of the minimum wage after 2004 and the growth in formalization of the sector as a result of mobilization of domestic workers for their rights (Figure 4).

Figures:

Figure 1 : Diagram comparing average income per social group (white men, white women, black men, black women) in 2018 in Real (R$3.60 = $1.00) (source: IBGE)

Figure 2 : Graph comparing average monthly wage of domestic workers with a formal work license (left) and without (right) in 2018 in Real (R$3.60 = $1.00). (note: Blue line represents minimum wage) (Source: PNAD)

Figure 3 : Graph comparing average monthly wage of female black and white domestic workers across regions in Brazil in 2018 in Real (R$3.60 = $1.00) (Source: PNAD)

Figure 4 : Graph showing evolution of average monthly wage of female domestic workers from 1995-2018 in Real (note: Value of Real oscillated a lot during this period, therefore, for simplicity I will not include it)

Analysis

Mobilizing “Intersectionally” : How Domestic Workers used their Race, Gender and Class to Succeed

The data above reveals how intersectional the problematic reality of domestic workers in Brazil is[35]. Domestic workers are disproportionately black women, largely because of their historical place in society. As mentioned above, black women represent 63% of all domestic workers and 18.6% of black employed women are domestic workers. Their past is marked by the struggle of slavery, which left black women in an economically vulnerable position. Additionally, because of their race and gender, they encounter further obstacles when seeking employment due to the heavily racist and sexist culture in the country. Not surprisingly, therefore, black women have to settle for inferior job opportunities, such as domestic work, which implies poor working conditions and little financial prosperity. Thus, it is clear that when discussing the challenges of domestic workers, it is not enough to simply focus on them as a unitary group, but rather we should acknowledge that their challenges are intrinsically related to their race, class, and gender too.

This was exactly what Laudelina de Campos Melo, who founded the Association of Domestic Workers in Sao Paulo in 1936, recognized. Laudelina began the movement for domestic workers’ rights because at the time president Getulio Vargas established employment laws for various forms of work, but excluded domestic workers[36]. His decision stemmed from the common perception of care work as “not real work” which was even more prevalent at the time since social norms that depreciated women were only beginning to change. Therefore, the understanding of care/domestic work as merely housewife duties and undeserving of monetary compensation was widely accepted.

Thus, Laudelina’s primary goal was to disrupt the conception that domestic workers weren’t real workers and therefore didn’t deserve to be paid[37]. Changing this widely accepted social norm was essential in breaking through the long-standing problematic perception of care work, and in turn allowed the issue to be regarded as a political concern. Laudelina succeeded in making domestic workers’ rights an issue worth discussing in policy-making by dialoguing with different movements in her local town, connecting their struggles with domestic workers’ struggles, and then expanding their influence nationally. Soon she became an activist of the Black Movement (Frente Negra Brasileira) and had the support of the Communist Party and the workers’ movement[38]. Her dialoguing efforts culminated in the first law allowing domestic workers to have a formal work license in 1972[39] – a major conquest that represents how she was able to shift the perspective of domestic work from “not real work” to “deserving of rights and regulation”.

Building on the legacy of Laudelina, domestic workers connected their struggle for rights to their struggle as black, poor women in Brazil for years to come[40]. Each aspect of their identity (race, gender and class) helped them achieve some change that made them advance many steps closer the advances previously mentioned: a significant increase in the number of domestic workers with a formal work license, and a significant increase in their average wage (Figures 2 and 4). While the Constitutional Amendment of 2012 was their most important conquest – as it gave them equal rights to other workers (established working hours, paid leave, and protection) and led to the increase in formality as more workers seized to formalize their license to get the rights[41] – we have to recognize that this conquest was a product of years of intersectional struggle.

Race

Regarding race, domestic workers’ labor unions would constantly note the similarities between domestic work and slavery, highlighting for instance, how the “maid’s room” alluded to the infamous slave quarters[42]. This relationship encouraged them to ally themselves to various organizations of the Black movement, and, more recently, to seek support from Black parliamentarians.

Gender

The feminist movement also greatly helped domestic workers take their demands to the Constituent (In Brazil, the Constituent is the political organ responsible for the elaboration of constitutions) by including policy proposals that exclusively targeted domestic workers’ rights[43]. Therefore, without the feminists their demands would not have been included in the Constituent, which was a major step towards getting their demands recognized in the political sphere. According to domestic worker Lenira de Carvalho, “in the constitution we did not have support from the National Trade Union Center, who brought our demands to the frontline were the feminists”[44].

Class

Finally, the connections between domestic workers’ demands and class inequality were always visible. As Laudelina argued, they were the backbone of Brazilian society. She pointed out that domestic work is highly lucrative for the country because it allows the wealthy to work without wasting time with domestic duties[45]. Laudelina questioned this unfairness as a consequence of inequality and until today domestic workers’ are tightly aligned to the Workers Party which works to combat this reality. In fact, it is important to note that domestic workers’ connection to the PT enabled the National Federation of Domestic Workers (FENATRAD) to negotiate directly with the left-wing government between 2003-2013 and press them for the 2012 Amendment[46], which, as we have seen, bred numerous social benefits for them.

To What Extent Does Intersectionality Help a Movement?

A study conducted by Louisa Acciari between 2015 and 2017 found that the more social identities are incorporated into domestic workers unions’ analysis and discourses, the broader their alliances are, and the more successful the unions can be[47]. She recognized three different modes of alliance: rigid autonomy, critical alliance, and encompassing union. Rigid autonomy, which refers to the refusal to build alliances, was implemented by the unions in Sao Paulo and Franca as they did not seek support from other organizations, arguing that domestic workers’ oppression is primarily a class-based labor concern. This isolation limited their capacity to recruit members and mobilize, therefore even though Sao Paulo has over a million domestic workers, the union had just about fifty members. Critical alliance, which refers to having informal relationships with stakeholders and forming alliances just occasionally, was implemented in a few cities of Rio de Janeiro where unions allied to the revolutionary branch of the church to influence their discourse on class and their modes of organizing. Their class-oriented approach led them to join the National Trade Union Center and the Workers Party, and conceded some of their leaders seats in local councils. Finally, encompassing unionism is a strategy implemented by the union of Campinas that focuses on black women’s empowerment besides, of course, domestic workers’ labor rights. The union of Campinas has been inserted in multiple social movements, which allowed them to reach domestic workers, gain visibility and recruit new members.

Interestingly, the study found that while domestic workers are thankful for the feminist movement’s support of their demands, they establish a clear line between themselves and feminists. This occurs because the feminist movement is seen as something belonging to upper-class white women, distant from domestic workers’ reality. Bernardino Costa (2015) argues that many domestic workers believe they are maintained in a lower social position so that richer white women can emancipate themselves from housework[48]. Domestic workers’ understanding of the feminist movement, therefore, is very much affected by class and race and their history of exploitation with the social group that leads the feminist movement in the country.

Acciari concluded that across the six local unions she studied, class and race appear to be a more articulate form of oppression than gender. The largest influence was when the black movement supported the creation of the first Association of Domestic Workers in 1936, and the fact that domestic workers’ close ties with the Workers Party led them to transform their local associations into proper trade unions in 1988 and to be affiliated to the largest national center of workers[49].

Undoubtedly still, addressing their position as poor, black, and women, domestic workers led domestic workers to more effective forms of mobilization and empowerment. Their intersectionality illuminated cmon forms of oppression with other social actors and enabled them to organize collectively against them. Moreover, the intersectional aspect of their struggle allowed them to share experiences of oppression and discrimination, which in turn made them more aware of the collective aspect of inequalities and more inclined to mobilize for change.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis conducted in this paper, therefore, it is fair to conclude that if Brazilian domestic workers had not mobilized intersectionally, they would not have achieved the rights presented in the 2012 Constitutional Amendment. Laudelina de Campos Mello was a key figure in the trajectory of domestic workers as she ended the flawed perception of domestic work as “not real work”, and opened a path for future domestic workers to bring their demands and concerns into the political sphere. However, she was only able to shift such perspective by dialoguing with the black, workers’ and feminist movement. This strategy was undoubtedly fundamental for domestic workers’ movements as, according to Acciari’s studies, social movements succeed more when they form alliances in line with their different identities. These ties allowed her to integrate domestic workers’ demands into different spaces, further spreading their message and influence across the country. For decades after her creation of the first association of domestic workers in 1936, Laudelina served as an inspiration for domestic workers who continued to strengthen their intersectional identity and form alliances with other movements in order to achieve change.

The success domestic workers achieved is evident in the increase in the number of workers with a formal work license (which, as Figure 2 shows, ensures higher wages) and in the growth of their average wage in the past decades (Figure 4). Both of these changes imply that domestic workers now live a more respectable life, that they have a chance at economic empowerment, and that they can stand up for their rights if they feel violated. In other words, these changes made domestic workers worthy of real citizenship. Therefore, thanks to the intersectional efforts of domestic workers across Brazil, thousands of black low-income women in Brazil have rose out of their marginalized and silenced state and into a more equitable society where they stand a chance of prospering.

However, even though these conquests are a sign that conditions might continue improving for domestic workers in the future, it is important to recognize that the average wage in 2015 still remained below the national minimum wage[50]. Additionally, even though there have been advances in how many domestic workers have a formal work license – in 1995 the number was 17.8% and in 2015 30.4% [51] – the percentage still remains extremely low and the consequences are concerning. Social change is a process and it is fair to say that domestic workers are in the right path or, at least, that they are familiar with tools that lead to the right path – and those are, of course, intersectional approaches to social change.

Works Cited

Acciari, Louisa. “Practicing Intersectionality: Brazilian Domestic Workers’ Strategies of Building Alliances and Mobilizing Identity.” Latin American Research Review 56, no. 1 (2021): 67-81.

Blofield, Merike, and Merita, Jokela. “Paid domestic work and the struggles of care workers in Latin America.” Current Sociology 66.4 (2018): 531-546.

Bernardino-Costa, Joaze. “Colonialidade do poder e subalternidade: os sindicatos das trabalhadoras domésticas no Brasil.” Revista Brasileira do Caribe 7.14 (2007): 311-345.

Bernardino-Costa, Joaze. “Colonialidade e Interseccionalidade: o trabalho doméstico no Brasil e seus desafios para o século XXI.” Igualdade racial no Brasil: reflexões no ano internacional dos afrodescendentes. Brasília: Ipea (2013): 45-58.

Bernardino-Costa, Joaze. “Controle de vida, interseccionalidade e política de empoderamento: as organizações políticas das trabalhadoras domésticas no Brasil.” Estudos Históricos (Rio de Janeiro) 26 (2013): 471-489.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and

Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (1991):

1241-1300

Fontoura, Natália, et al. “Retrato das Desigualdades de Gênero e Raça–1995 a 2015.” Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA). (2017). Available at: http://www. ipea. gov. br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/170306_retrato_das_desigualdades_de_genero_raca. pdf .

Goodwin, Jeff and Jasper, James M. “Editor’s Introduction” in Goodwin, Jeff and

James M. Jasper (editors). The Social Movements Reader. Cases and Concepts. Malden, MA /

Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell. (2015)

IPEA. “Os desafios do passado no trabalho doméstico do século XXI: reflexões para o caso brasileiro a partir dos dados da PNAD contínua.” Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA). (2019): 01-02.

IPEA. “Retrato das Desigualdades de Gênero e Raça: 4a Edição.” Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA). (2011). Available at: https://www.ipea.gov.br/retrato/pdf/revista.pdf

Robinson, Fiona. “Global care ethics: Beyond distribution, beyond justice.” Journal of Global Ethics 9.2 (2013): 131-143.

Women, UN. “Progress of women in Latin America and the Caribbean: Transforming economies, realizing rights.” Panama City: UN Women Regional Office for the Americas and the Caribbean (2017).

Vuola, Elina. “Intersectionality in Latin America? The possibilities of intersectional analysis in Latin American studies and study of religion”. Serie HAINA VIII : Bodies and Borders in Latin America. (2012)

[1] IPEA, 2011

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] Bernardino-Costa, 2013

[6] Robinson, 2013

[7] Ibid

[8] Robinson, 2013

[9] Blofield & Jokela, 2018

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Crenshaw, 1991

[13] Blofield & Jokela, 2018

[14] Ibid

[15] Blofield & Jokela, 2018

[16] Ibid

[17] UN Women, 2017

[18] Blofield & Jokela, 2018

[19] Vuola, 2012

[20] Ibid

[21] Goodwin & Jasper, 2015

[22] Ibid

[23] Ibid

[24] IPEA, 2019

[25] Ibid

[26] IPEA, 2011

[27] IPEA, 2011

[28] IPEA, 2017

[29] IPEA, 2019

[30] Ibid

[31] IPEA, 2019

[32] Ibid

[33] Ibid

[34] IPEA, 2017

[35] Crenshaw, 1991

[36] Bernardino-Costa, 2007

[37] Bernardino-Costa, 2007

[38] Bernardino-Costa, 2007

[39] Ibid

[40] Acciari, 2021

[41] Bernardino-Costa, 2013

[42] Acciari, 2021

[43] Bernardino-Costa, 2007

[44] Ibid

[45] Acciari, 2021

[46] Ibid

[47] Ibid

[48] Ibid

[49] Ibid

[50] IPEA, 2019

[51] Ibid