10 Women’s Access to Education in Latin America: An Unsolved Problem- Rowan Hoel

Rowan Hoel

Rowan Hoel

Professor Hernandez-Medina

Gender and Development in Latin America

I. Introduction:

Worldwide, 83% of women are literate compared to 90% of men (UNESCO 2019). This gap of 7% is troubling, as educational attainment is predictive of later success in labor markets and allows for economic autonomy. Outside of the private sector of economic autonomy, equal participation in the labor market for women and men increases the national growth of the economy and globalization efforts (Beneria et al 2016). Women’s participation in education and their education more broadly only has positive implications for human rights issues, the economy, and autonomy yet it is still a major issue. Women in Latin America do not have equal access to education and this is only furthered by differences in identities including class, race, and ethnicity.

To analyze this issue of educational access, it is important to examine child labor in Latin America. Male students are more likely to participate in outside-of-the-house, paid labor than female students. However, female students are more likely to participate in household unpaid labor, both of which have some impact on educational access (Middel 2020). Additionally, students who participate in labor outside of the home are more likely to come from an improvised background, making this participation essential to a household’s success. Furthermore, an intersectional lens must be applied to issues of educational access. Children who are upper-class, for example, will have a significantly better chance of achieving academically as they are less likely to participate in labor. This extends to unpaid domestic work as well, as families with more means are more likely to outsource their necessary domestic work (Beneria et al 2016).

This paper will address issues of labor, class and gender in terms of educational access. Ideally, this would extend to issues of race and sexual orientation as well, however, the literature presented has not been able to address these issues in terms of educational access yet. Thus, this also serves as a call to action for more research, as the problem of educational access will only be solved once all factors of identity are considered.

II. Literature Review:

IIA. Educational Access:

In order to successfully evaluate educational access for women in Latin America, it is important to understand key concepts in the academic area. To begin, it is imperative to understand the definition of educational access. This is explored by Keith Lewin in his investigation of educational systems titled Educational Access, Equity and Development: Planning to Make Rights Realities. He defines educational access as “on-schedule enrollment and progression at an appropriate age, regular attendance, learning consistent with national achievement norms, a learning environment that is safe enough to allow learning to take place, and opportunities to learn that are equitably distributed” (Lewin 2015:29). This definition is multi-faceted, and allows room for additions and adjustments based on an individual country or region’s needs, history, and population makeup. While these factors of educational access can stem from a variety of reasons, the most potent avenue for exploration of them, according to Lewin, come from “the problems others face, the objectives they seek, the routes they try, the outcomes they achieve, and the unintended results they produce all deserve analysis” (Lewin 2015:6). He also identifies some of the main reasons for the inequitable access to education for students across the world, which include poverty, race and gender (Lewin 2015).

IIB. Intersectionality and Patriarchal Influence:

Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality in her 1993 piece Mapping the Margins. Crenshaw states in an interview that intersectionality is a “lens through which power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LGBTQ problem there” (Crenshaw 2017:June 10:interview). She argues that intersectionality is a theory that allows an analysis of various overlapping marginalized identities. In Mapping the Margins, she divides intersectionality into three categories: structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality. The first, structural intersectionality, focused on battered women’s shelters in minority communities around Los Angeles. She found that the workers were not just confronted with the issue of violence against women, but the complex identities that got them to that position including a combination of class, race, and gendered discrimination. The second part, political intersectionality, argues that women of color are in a unique position in terms of political participation as they are often invested in conflicting political agendas. The final part, representational intersectionality, focuses on sexual violence against Black women, and argues that the representation of women of color in media “ignore[s] the intersectional interests of women of color” (Crenshaw 1993:1283). Overall, intersectionality can be extended to analyze disenfranchisement of people who exist with multiple marginalized identities.

Similarly, Elina Vuola discusses the role of intersectionality in Latin American feminism in her piece Intersectionality in Latin America. She states that “issues of race, class and ethnicity have been part and parcel of Latin American feminism and feminist theorizing from early on, even when not always without conflict and critique from minority women” (Vuola 2012:138). She argues that while it is important to theorize about intersectionality, the real work will be done through concrete examples. She believes that this is the way that intersectionality will gain tangible force in the region. She also discusses the different cultural power structures that come into play in regards to intersectionality: for example, one “difference” may be more potent in Latin America than in Europe (Vuola 2012). She suggests that some differences are more fixed and stable while others are malleable to the cultural moment. Overall, she believes that intersectionality will be most useful when applied to real life situations and lived experience.

On another note, Audre Lorde discusses the ways patriarchy, sexism, racism, and homophobia penetrate spaces that are meant to be about liberation in her piece “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”. She begins her piece by stating that she was invited to participate in a humanities conference where she would discuss papers on the role of difference for American women. She states that the only Black women who presented were found in the last hour, begging the question of: “what does it mean when the tools of the racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy?” (Lorde 1984:1). She, as a Black lesbian woman, argues that the patriarchy trains women to either ignore the differences among them or use these differences to separate themselves from each other. Instead of continuing this cycle of separation and ignorance, she argues that the differences should be embraced and used as agents of change (Lorde 1984). In other words, female liberation can never occur while using the same framework as the oppressor; difference needs to be celebrated and appreciated in order to bring radical change.

IIC. Child Labor and Economic Autonomy:

Lourdes Beneria et al discuss the role of unpaid household labor on the economy and women’s issues in their piece “Paid and Unpaid Work: Meanings and Debates”. They write that “since a substantial part of women’s work performed within their households and communities has traditionally been unpaid, it was excluded from labor force statistics and national income accounts” (Beneria et al 2016:183). Women’s household labor has been consistently undervalued in the labor market economy leading to lack of representation, essentially making women’s work invisible. In addition to this, families in a higher economic class are able to outsource their labor to a paid worker while women in low income households are left to take care of the household labor. This can have differing effects, the first being that low-income women do not have the time nor have the resources to participate in paid work, the second effect is that low-income women have to work a “second shift” of unpaid work, leading to less time for other tasks (Beneria et al 2016). While there has been an uptick in statistical evaluation of unpaid labor, Beneria et al argue that there needs to be a better formula for counting unpaid labor by women. When this is achieved, it will potentially open doors to policy formation to protect and support unpaid household labor for women.

IID. Strides towards Equality/Governmental Influence:

Donna Guy discusses the constructions of femininity and masculinity in Latin America in her piece “Gender and Sexuality in Latin America”. She notes the patriarchal want in men to be the head of household, and how this detrimentally affects women’s choice in pursuing education and careers (Guy 2010). Most importantly, she states that: “The rise of universal state education and mandatory military service, as well as reforms of the civil code that allowed married women to work and keep their own wages, directly challenged patriarchal rights to select occupations for their family and decide whether wives should work or not” (Guy 2010:10). Latin American governments have been forced to expand educational access for women. Lastly, there have also been movements to increase access and safety for women and LGBTQ groups in schools in recent years. Marlise Matos touches on these differences in her piece “Gender and Sexuality in Brazilian Public Policy”, where she states: “Also noteworthy is the vital expansion of initiatives on education and on ending violence for both of these groups (women and lgbti* persons). This comparison reveals that the inclusion of movement issues was oriented in distinct directions in the periods reviewed” (Matos 2018:163) The influence of the government on issues of educational access is important to understand as it has the ability to drastically change the lives of women who seek access to better educational opportunities.

These factors and historical patriarchy have negatively impacted women’s access to education throughout Latin America. In order for these gaps to be explained, it is important to recognize the aforementioned cultural expectations for women in Latin America. The effects of these bounds, and less access to education for women, intrinsically affects Latin American development as women do not have the resources/education to participate in the economy in the way that they are fully capable of. The following will expand on the ideas mentioned above, and will add to the academic discourse and the project of problem solving better educational access for Latin American women.

III. Case Study: Labor and Educational Attainment

IIIA. Child Unpaid/Paid Labor

In terms of class, “the richest 20% are, on average, five times as likely as the poorest 20% to complete upper secondary school” (UNESCO 2021). This stratification can likely be explained by the need for children facing poverty to bring in an income for the family, while children in the upper 20% do not have this same pressure (UNESCO 2021). Women are particularly vulnerable to this situation, as they are often responsible for unpaid domestic work. Latin American women spend between 30.7- 45.2 hours per week on unpaid domestic labor, leaving less time for pursuit of education or paid labor opportunities (Hernandez-Medina, 2021). This statistic varies based on income level as well as sexual orientation, with women in heterosexual couples carrying much more responsibility for unpaid labor than same-sex relationships.

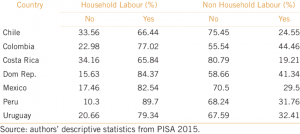

Child labor can be broken into two categories, the first being work inside of the home and the second being work outside of the home. Male children, specifically in Latin America, are more likely to participate in work outside of the home, due to constructions of masculinity and the idea of the “breadwinner” (Middel et al, 2020). This is exacerbated for male children living in poverty, as their contribution to household income is vital to the financial stability of the family. According to data drawn from the entire region of Latin America, female children are more likely to complete household work, such as childcare, cooking, and cleaning (Middel et al 2020). This differentiation between household work and outside of the house work leads to differences in the skilled breakdown between male and female children, as male students are able to develop skills for a future career that female students do not have the same opportunity to earn (Middel et al, 2020). Furthermore, the rates of educational attainment and employment for women in low income countries is significantly lower than other richer countries, showing the complexity of combining gender and poverty (Middel et al 2020). Figure A shows the percentages of children working inside and outside of the house in Latin America:

IIIB. Educational Attainment Statistics:

In terms of strictly gender gaps in educational access, the literacy rates, attendance rates, and progress rates vary per country in the region. Some countries in Latin America, such as Mexico and Peru, have done a significantly better job at closing the gender gap than other countries such as Belize and Guatemala (Roberts 2012). In Mexico, girls and boys have very similar literacy rates, with male students at around 99% and female students at about 98% (Roberts 2012). They are also comparable in attendance rates, with both genders attending school approximately 97% of the time; they are also equal in completion of primary school at 104% (Roberts 2012). Peru has similarly made significant strides to end the gender gap in education, with a literacy rate of 96% for both genders and attendance rates of 98% for males and 97% for females (Roberts 2012). Peru still faces some gender-based stratification in education, with about 90% of male students continuing past primary school and only 87% of female students continuing (Roberts 2012). However, only 3% of female students remain out of school, proving it to be very close to true gender equality in schooling.

While these statistics are promising, these rates are not consistent across all of Latin America. Two countries that still have significant progress to make include Belize and Guatemala. Belize maintains similar rates in attendance between male and female students at 95%, and faces a small gap in literacy rates between male students, 77%, and female students 76% (Roberts 2012). However, Belize’s educational gap widens when considering continued education to fifth grade, where male students rest at a 95% completion rate and female students are at a 93% completion rate (Roberts 2012). Additionally, the gender gap in completion of primary school is particularly concerning, with 98% of female students completing and 113% of male students completing, a 15% gap (Roberts 2012). Furthermore, 9% of female students in Belize are not enrolled in school, which is significantly higher than countries who have, statistically, closed the gender gap (Roberts 2012).

Guatemala is in a similarly troubling position in terms of the educational gender gap. The attendance gap is the first struggle, with male students attending school about 95.7% of the time and female students attending around 91.3% of the time (UNICEF 2005-2010). Youth literacy is also concerning, with around 89% of male students achieving literacy and 84% of female students, a large gap of about 5% (UNICEF 2005-2010). In terms of primary school completion, the gap furthers, with male students completing at about 87% and female students completing at about 81% (Roberts 2012). While Guatemala has a lower rate of female students not attending school at 5% than Belize, it is still significantly higher than nation-states that have effectively closed the gender-based educational gap.

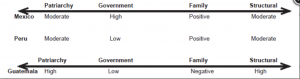

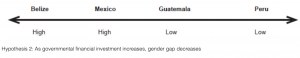

Roberts looks at different factors that may contribute or hinder educational access. These include the patriarchy factor, measured by th e Gender Inequality Index, the family factor, which looks at education rates of the parents, specifically the mother, governmental funding, and its effects on access, and the structural factor, which includes indigenous children and children from rural areas (2012). From this analysis, Roberts found that the most significant factors were the patriarchy factor and the family variable. This is interesting because governmental funding was found to not significantly increase educational access. Figure B shows the results of this test and which variables had the most influence. Figure C, below, shows the implications of Governmental spending on educational access:

e Gender Inequality Index, the family factor, which looks at education rates of the parents, specifically the mother, governmental funding, and its effects on access, and the structural factor, which includes indigenous children and children from rural areas (2012). From this analysis, Roberts found that the most significant factors were the patriarchy factor and the family variable. This is interesting because governmental funding was found to not significantly increase educational access. Figure B shows the results of this test and which variables had the most influence. Figure C, below, shows the implications of Governmental spending on educational access:

These statistics are very concerning, considering the impact and importance that education has on later life ventures. To specify, Latin America has an extremely high rate of waged workers and non-contract workers, represented by the “petty bourgeoisie” and the “informal proletariat” (Portes, Hoffman 2003). These classes, specifically the informal proletariat being the non-contract workers, unpaid family workers, and casual vendors made up between ⅓ and ½ of the economically active population (Portes, Hoffman 2003). An increase in educational opportunity and educational equity could potentially lead to an increase in workers in the management level positions, thus, leading to an increase in economic means for the population as a whole. Educational access, as a whole, is key in creating economic autonomy for women, allowing them more options in terms of family life and employment.

IV. Analysis

IVA. Educational Access:

The data presented above illuminates the difference in progress across different Latin American countries. However, there are gaps in the literature, represented by a lack of an intersectional analysis, leading to several questions about educational access. Given my interest in labor division and economic autonomy, the question of the correlation between child labor and limited access to education arrises. On the discussion of child labor, it is important to examine its correlative effect on educational access. The first problem that arises in completing this analysis is the definition of educational attainment itself. While this definition provided by Lewin includes attendance rates, enrollment, and years of schooling, actual quantitative measurements on learning rates is not addressed, leading to a lack of true data on how much students are learning (Middel et al 2020). While there are studies on literacy rates (as previously mentioned above), I argue that this still falls short and that measuring educational attainment is a much harder feat than it is often prescribed to be. In order for the data to be representative of a larger population, Crenshaw and Vuola’s discussions on intersectionality need to be considered. The data would be much more compelling if the intersections of race, class, sexual orientation, and gender were considered, as intersectional identities cannot be ignored in factoring access to education.

IVB. Child Labor and Economic Autonomy:

Middel’s et al study of child labor in the household versus outside of the household has shown significant negative affects for working children. Specifically, children who work outside of the home are significantly more likely to have lower achievement in school. As male students are more likely to participate in child labor outside of the home, they are more likely to have negative affects on their school achievement (Middel et al 2020). This is significant to the question of gender achievement in school because it illuminates the complexity of the issue of educational attainment, thus, showing the impossibility of claiming that one factor (such as gender for the purpose of this analysis) is the only factor hindering educational access. However, even though male working students achieve at significantly lower rates than their non-working counterparts, female students are still shown to be underperforming in educational pursuits across Latin America, proving that gender is an extremely significant factor in low educational achievement (Middel et al 2020). Additionally, an application of Beneria’s et al work on the invisibility of women’s labor inside of the house is important to consider. Given the low statistics on how much unpaid labor women are involved in, it is possible that Middel’s et al study was unable to capture the entirety of the problem of unpaid labor. Lastly, to apply Donna Guy’s framework to Middel’s et al piece, it is interesting to consider the role of semi-recent law shifts that allow for women to earn their own wages outside of marriage (Guy 2010). Women’s labor participation may see an uptick in the years to follow as policies are expanded to include women in the paid labor markets, especially in industries that require education.

IVC. Intersectionality and Patriarchal Influence:

Although child labor does not have a seemingly high affect on women’s educational access, the issue of patriarchy plays a significant role in the conversation. In Latin American countries where the rate of patriarchy is higher (based on world bank reports of government leaders, women in the workforce, and the Gender Inequality Index) the educational achievement of women is also lower (Roberts 17). In terms of Crenshaw’s intersectionality, the population of indigenous women as well as women living in rural communities does not have a significant effect on the gender gap as a whole across the region (Roberts 17). This finding is of particular interest as these factors should, in theory, affect the gendered gap in educational access significantly.

IVD. Strides towards Equality/Governmental Influence:

It is also interesting to note that governmental implementation of financial investment in education does not have a significant correlative effect with improving educational access for women (Roberts 2012). This is important to discuss because it suggests that the solution to educational equality will not be a simple fix of governmental support. It also suggests that cultural norms such as hegemonic masculinity and patriarchy, as discussed by Donna Guy in her piece “Gender and Sexuality in Latin America”,will have to majorly shift in order to achieve true gender equality. Additionally, Audre Lorde’s idea that the master’s tools will never be able to dismantle the master’s house is applicable here. The culture of hegemonic masculinity and patriarchy are used to suppress women and separate their issues in Latin America and thus, this culture will have to dramatically change in order to bring women’s access to education. A “quick-fix” method of governmental spending will not be able to dismantle this harmful culture, only a revolutionary culture shift that appreciates differences will bring about this change.

In addition to this, it is important to consider the quality of governmental financial investment in education. Since its contributions do not lead to significant positive change, it is important to investigate the quality of the investment. If governments are just throwing money at the problem, without a strategic plan for where the money will go, the quality of the spending, in theory, will decline. Perhaps more research is needed into what exactly is necessary for the government to invest in in terms of educational access. Quality investment in education is necessary to provide more educational opportunities for women.

V. Conclusion:

The issue of educational access is an extremely complex one without a simple answer. Patriarchal influence is extremely relevant to women’s access to education. Although women are included in many educational ventures, they are still not equally included in the labor market. There needs to be an institutionalized way to ensure women’s continual access to the labor market, especially women with various intersectional identities such as indigenous, afro-descendent, and low income women. This can begin when there is more research about women with intersectional identities. As long as women are seen as inferior to men, as the patriarchal state suggests, it will continue to be extremely difficult to include women in the labor market despite their educational pursuits. Women’s economic autonomy is extremely important as it allows women the ability to make their own choices. Without these correlative effects, women will continue to be trapped in subordinate positions to their male counterparts.

Additionally, labor has an obvious correlative affect to the ability to access education in Latin America. Students who participate in outside of the house labor are significantly more likely to underperform in schools. This issue overarchingly affects low-income students, as they are heavily relied on for another household income. Additionally, there needs to be more qualitative and quantitative information on women’s work inside the household, as, although the Middel study found its effect statistically insignificant on educational access, it remains one of the only studies that focuses on this issue. More studies on unpaid labor would allow for this work to become more visible, as Beneria et al argues. I would propose that governmental programs should be prioritizing these issues, as their funding could significantly help solve this problem.

Finally, there is still much research that needs to be done in terms of educational access for women. The most important research, I believe, will focus on the intersectional identities of women in Latin America, as the most marginalized groups are not represented in the literature. In addition to this, it is important for the research to consider differences in the cultural context of Latin America, as Vuola argues, intersectional differences have different prioritization in various cultural moments.

VI. References:

Beneria, L., Berik, G., & Floro, M. (2019). Gender and Development: A Historical Overview. In Gender, development, and globalization economics as if all people mattered. essay, MTM.

Beneria, L., Berik, G., & Floro, M. (2019). Paid and Unpaid Work: Meanings and Debates. In Gender, development, and globalization economics as if all people mattered. essay, MTM.

Crenshaw, K. (n.d.). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review.

Guy, D. J. (2012). Gender and Sexuality in Latin America. Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195166217.001.0001

Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, more than two decades later. Columbia Law School. (2017, June 8). Retrieved December 14, 2021, from https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later

Lewin, K. (2015). Educational access, equity, and development: planning to make rights realities. UNESCO IIEP .

Lorde, A. (2018). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s House. Penguin.

Middel, A., Kameshwara, K., & Sandoval-Hernandez, A. (n.d.). Exploring trends in the relationship between child labour, gender and educational achievement in Latin America. story.

Matos, M. (n.d.). Gender and Sexuality in Brazilian Public Policy.

Portes, A., & Hoffman, K. (2003). Latin American class structures: Their composition and change during the neoliberal era. Latin American Research Review, 38(1), 41–82. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2003.0011

Roberts, E. (2012). The Educational Gender Gap in Latin America: Why Some Girls Do Not Attend School. Inquiries Journal, 2(1).

Vuola, E. (n.d.). Intersectionality in Latin America? The Possibilities of Intersectional Analysis in Latin Americas Studies and Study of Religion.

.