9 Disenchantment in Pink Tide development: gender, class, and women’s economic autonomy in a leftist Latin America

Liam Gilbert-Lawrence

I. Introduction and historical review

At the turn of the 21st century, leftist administrations began to take power across Latin America. The “Pink Tide” (named so for their notably leftist agendas, though not quite “Red” or Communist) in Latin America saw a new wave of socialist politicians closely following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. At this point in geopolitical history, the United States had essentially won the Cold War. Capitalism triumphed over communism, subduing its ultimate foe in a bloody quest for hegemony. This, coupled with the economic crises of state-controlled development models in the 1980s, disappointed economists and leftists across the board (Levitsky and Roberts 2011). Latin America plunged deeper and deeper into global markets, further narrowing governments’ policy options (Levitsky and Roberts 2011). Now, even remotely progressive policies seemed not only unpopular but impossible as the neoclassical model sank its teeth into Latin America.

This seemingly absolute repression did not long endure. The plights of neoliberalism (on which the theoretical framework of this paper elaborates) took shape and gave way to loud criticism and social movements. By the late 1990s, anti-neoliberal thought had amassed considerable popularity, with some zealous leftists even beginning to run for office. Hugo Chávez of Venezuela led this front, winning the presidency in 1998. Additionally, the 1990s saw a shift in U.S. priorities: the imperial superpower, along with the rest of the world after 1991, saw little prospect of any serious communist threat anywhere in the near future. Thus, the self-appointed hegemon relaxed its heavy emphasis on regime change in foreign policy (Levitsky and Roberts 2011). With relative U.S. leniency towards budding leftist enterprises and increasing social and economic issues arising from neoliberal policies, the Latin American left quickly advanced. Characters like Hugo Chávez, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Brazil), and Evo Morales (Bolivia) rose to power on platforms of social and economic reform, vowing to redistribute wealth and bolster the welfare state (Levitsky and Roberts 2011). By 2009, the majority of Latin American countries had undergone leftist administrative takeovers.

Considering that such administrations rose to power on such progressive platforms, one would think women’s place in society would consequently be elevated. Unfortunately, this was not the case. While there is evidence for general poverty alleviations and reductions in income inequality in most Pink Tide nations (Lustig and López-Calva 2010; Enriquez and Page 2018; Loureiro 2018; 2019; Lind 2019), this paper argues that little to no effective effort in gender and development policy was made and women’s economic autonomy floundered. From 1999 to 2011, the amount of Latin American women living in poverty and indigence rose by more than 20 percent (ECLAC 2012). This paper articulates some of the ways in which Venezuela, Argentina, Bolivia, Perú, El Salvador, Paraguay, Uruguay, Ecuador, Chile, Nicaragua, and Brazil failed to support women’s economic autonomy during their Pink Tide years. Aside from the shared trends among these countries, a specific case study on Ecuador’s turn to the Left will further support this conclusion.

Among other reasons not discussed here, these administrations failed to support Latin American women due to their failure to address intersections of gender and class. Furthermore, their preservation of harmful neoliberal strategies in macroeconomic development, arrangement of labor markets (microeconomics), and maternity/paternity leave policies perpetuated the marginalization of vulnerable social groups. Equipped with a framework surrounding gender, class, and development, we may begin to examine the faults of the continental leftist movement that carried with it so much potential.

II. Theories on gender, class, and development

A brief discussion on ideology, neoliberalism, and material analysis

Before one begins to analyze women’s economic autonomy during the Pink Tide, certain concepts relating to gender and class in Latin America must be addressed. Firstly, it is necessary to put aside ideological convictions when analyzing women’s economic autonomy in Latin America. Without this framework, simply electing socialist leaders that outwardly endorse progressive policies might seem like a uniform fix for gender inequality; however, this has historically never been the case, especially not with Pink Tide nations. In Seeking Rights from the Left, Amy Lind captures this perfectly: “Ideology and party politics do not determine how gender and sexual rights are or are not addressed in Pink Tide contexts” (2019:x).

With that being said, this paper will also operate under the authoritative conclusion that the empirical applications of neoliberalism have accomplished little else in Latin America than to impoverish populations and exploit natural resources. In Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, Eduardo Galeano articulates the atrocities of imperialism and its contemporary byproduct, neoliberalism, in which “development develops inequality” (1997:3). Galeano explains that this “system has multiplied hunger and fear; wealth has become more and more concentrated, poverty more and more widespread” (1997:265). Neoliberalism, a relic of colonialism, is incompatible with productive efforts at development in Latin America.

Though not as woefully anti-capitalist as the overtures of Galeano, Alejandro Portes and Kelly Hoffman affirm the pitfalls of the neoliberal economic model specific to the 1990s. In Latin American Class Structures: Their Composition and Change during the Neoliberal Era, Portes and Hoffman outline an explicit, organizational framework of class in Latin America to guide them in their analysis, advocating for such a framework because of its “focus on the causes of inequality and poverty and not just its surface manifestations” (2003:43; emphasis added). Using this framework, Portes and Hoffman find that the 1990s neoliberal economic model—which immediately preceded the Pink Tide—expanded the informal sector while simultaneously increasing poverty and income inequality (2003). Not only were these societal afflictions amplified, but the social groups most susceptible to them grew larger.

Gita Sen and Caren Grown elaborate on the legacy of the overall colonial era on Latin American development in their work, Development, Crises, and Alternative Visions: Third World Women’s Perspectives. “The economic relations between developing and developed countries have tended to operate against the interests of the former so as to increase their vulnerability to external events and pressure” (Sen and Grown 1987: 29). Pink Tide macroeconomics did little to reverse these relations. Sen and Grown deliberate, adding an important qualifier to their criticisms of development trends: claiming that their argument is “not against export expansion per se. Rather, we [Sen and Grown] argue that export promotion under conditions of extreme inequality and landholding and income will not create the needed backward linkages to domestic production, and will probably worsen existing inequalities” (1987:34). As this paper will soon develop, inequality worsened under the Pink Tide while administrations placed heavy emphasis on such export promotions in macroeconomic policy.

Development with a lens on gender and class

Sen and Grown give important conclusions regarding harmful development, basing these conclusions on the paramount role of gender and class in drafting proper development policy (1987). The authors assert that development efforts must focus on low-income and historically oppressed women in order to be successful (Sen and Grown 1987). This is the case for three reasons:

First, if the goals of development include improved standards of living, removal of poverty, access to dignified employment, and reduction of societal inequality, then it is quite natural to start with women. […] Second, women’s work, undervalued and underremunerated as it is, is vital to the survival and ongoing reproduction of human beings in all societies. […] Third, in many societies women’s work in trade, services, and traditional industry is widespread (Sen and Grown 1987:23-24).

Each of the requirements articulated by Sen and Grown is absolutely necessary for the constructive implementation of any sort of poverty reduction or development effort. For starters, it would be foolish to ignore the primary requirement that Sen and Grown establish considering that the majority of the poor and disenfranchised around the world are women (1987). The following two are equally crucial: addressing the needs of poor women not only affects them but the development of the larger economy and continuation of society as a whole (Sen and Grown 1987). These three pillars create guidelines for progress in gender and development by looking at both gender and class. This intersectionality is pivotal in understanding how leftist administrations that experienced brief macroeconomic spurs

In the early 90s, Kimberlé Crenshaw cemented the concept of intersectionality to better explain the historical and modern-day oppression of black women (Crenshaw 1991). Since then, the term has become anything but cemented, proving relevant in various interactions where “power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects” (Crenshaw 2017). In this paper, the intersectional identities of poor women are essential in assessing women’s overall autonomy under Pink Tide administrations and economic reforms. This is especially so because Pink Tide economics preserved harmful aspects of their neoliberal and colonial predecessors that particularly marginalized low-income women.

Labor markets are central to the continued marginalization of women. Diane Elson captures this in her work, Labor Markets as Gendered Institutions: Equality, Efficiency, and Empowerment Issues, in which she details women’s role in the productive and reproductive economies and the discrimination they face in both. The productive economy, in which activities that generate income and market-oriented productivity are included, does not factor in the unpaid care work that replenishes the labor pool on which it relies (Elson 1999). These activities constitute the reproductive economy. Labor markets exist at the intersection of the two economies (Humphries and Rubery 1984) though they fail to acknowledge the work performed—largely by women—in the reproductive economy, an omission that drastically lowers women’s economic autonomy (Elson 1999). However, not all women are equally susceptible. Women with high access to income are able to subvert this intersection and re-enter the labor market as consumers, i.e. by hiring caregivers, babysitters, etc; alternatively, women who lack the capital to do the same are forced to take on the domestic care work themselves and join the reproductive market. The gendered labor markets that Elson describes disproportionately affect those at the intersection of gender and class: low-income women.

Pink Tide macroeconomics and microeconomics did not address this intersection of the reproductive and productive economies and thus turned a blind eye to poor women. In The Master’s Tools will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, Audre Lorde poses a critical question: “what does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy? It means that only the most narrow parameters of change are possible and allowable” (1984). Lorde wrote this in response to a lack of representation in feminist academic work within the United States, but it is relevant in the context of Gender and Development in Latin America as well. By merely tweaking the structures that oppressed poor Latin American women (and also the larger continent), the Pink Tide did not support women’s economic autonomy. This incompetency is present in the cases of several Pink Tide administrations that I will now present.

III. The case of women’s economic autonomy under the Pink Tide

Shared trends among nations

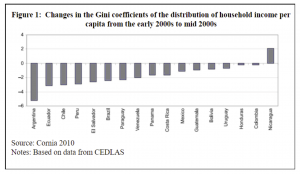

As stated previously, the decline in women’s economic autonomy occurred in spite of overall declines in inequality under Pink Tide administrations; I will begin this section by first cataloging data that supports the latter of these two trends, then the former. Figure 1 reveals significant drops in the Gini coefficients of the distribution of household income in Argentina, Ecuador, Chile, Perú, Brazil, El Salvador, Paraguay, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Uruguay during their leftist administrations with an average decline of 2 to 3 percentage points. The number of women without their own income in these Pink Tide nations dropped significantly between 1990 and 2010; data for poor women show a drop of nearly 20 percent and 10 percent for non-poor women; this largely due to widespread adoption of Conditional Cash Transfer Programs occurred throughout Pink Tide nations, offering monthly stipends to families (ECLAC 2012; Orloff 2006; Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni 2017).

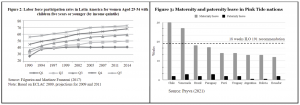

Despite these advancements, data from ECLAC 2012 also reveals that the femininity index of poverty and indigence rose by more than 20 percent in these countries during this same time period (2012). Notably, labor force participation among women slowed throughout all of Latin America after 2002, shortly after the rise of the Pink Tide (Gasparini and Marchionni 2015). The decrease in women’s entrance into the labor force was not of equal magnitude for all countries in Latin America; although Argentina, Venezuela, Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Perú, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil (note: I will refer to this conglomerate of states as “Pink Tide nations” for the remainder of this subsection for the sake of brevity) most notably experienced this trend (Gasparini and Marchionni 2015). For this reason, the trends depicted in Figure 2, showing data for all of Latin America, can be related individually to each of these countries.

By the time the Pink Tide had begun to take form, women aged 25-54 with college degrees had already reached a ceiling in labor force participation, at almost 90 percent, revealing that the slowdown in overall female labor force participation rate was largely due to fewer less-educated women entering the workforce (Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni 2017). Correspondingly, labor force participation rates for women in the bottom income quintile essentially flattened during this period, a trend most distinct among women with children five years old or younger (Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni 2017) and also among women who are either married or cohabiting with a partner (Gasparini and Marchionni 2015). See Figure 2.

A look into maternity and paternity leave policies also sheds light on women’s economic autonomy under these administrations. Figure 3 shows the amount of time granted for maternity and paternity leave in Pink Tide nations during their time in power and how they match up with recommendations from the International Labor Organization. This data was collected by Marisa Payva in research on progress in maternity, paternity, and parental leave policies enacted by Pink Tide administrations (2021). Paternity leave policies never extended past 10 days in most countries (Payva 2021). This encourages men not to take time off work to perform caring duties, reinforcing women’s role as primary caregivers in the reproductive economy (Payva 2021). Though this paper examines only the Pink Tide in regard to this reinforcement, it is also worth noting that the ILO has only ever published recommendations for women’s time off work and has never done the same regarding men’s time off.

Case study: neoextractivism in Ecuador’s turn to the Left

In addition to tracking shared trends among Pink Tide nations, a very representative case study on Ecuador proves useful in exhibiting the state of gender and development in Latin America’s turn to the Left. Rafael Correa, president from 2007 to 2017, led Ecuador through its Pink Tide years. Now, while the scope of this subsection is limited to the effect of Correa’s policy on women’s economic autonomy, I find it relevant and important to at least briefly mention Correa’s highly problematic stances on other areas of gender autonomy (including but not limited to gender and sexual rights, physical autonomy, and the indigenous feminist movement) and cite the work of other scholars that deliberate in-depth on this topic (Careaga 2019; Picq and Viteri 2019; Viteri 2019; Wilkinson 2019; Morales Hidalgo 2020).

Ecuador saw large macroeconomic gains and other general improvements under Correa. Improvements more specific to Ecuador than those described in the previous subsection include record low unemployment rates and a 10 percent decrease in poverty (Ray and Kozameh 2012; Grugel and Riggirozzi 2012). Much of this growth can be credited to massive increases in social spending under Correa (Wilkinson 2019). Correa’s model for development primarily relied on the extensive harvesting of Ecuador’s natural resources and sale to global markets (Wilkinson 2019). Eduardo Gudynas has since dubbed this model “neoextractivism,” a development tactic which he cites Venezuela, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay as having similarly employed under their respective leftist administrations (2012). Though economically fruitful, extractivism held the Ecuadorian economy and national budget highly susceptible to the volatility of the international markets, resulting in a massive economic downturn in 2015 (Wilkinson 2019).

Furthermore, these policies severely disadvantaged poor indigenous communities and, particularly, the women within them. Annie Wilkinson explains in her essay, A Lost Decade for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, that not only did the neoextractive model disregard Ecuadorian indigenous peoples’ land rights and safety, but that indigenous women residing near extraction sites experienced “elevated workloads, increased sexual and domestic violence, and environmental health problems—including those related to reproductive and maternal health, obstacles to political participation, and heightened exploitative sex trafficking” (2019:292). Extractive expansion has also impaired many indigenous womens’ source of income in the informal sector while simultaneously generating more male-oriented jobs in the formal sector (Valencia 2015; Wilkinson 2019). Poor, indigenous women existing under Pink Tide administrations in Venezuela, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay experienced similar attacks on their economic autonomy as their nations’ governments pursued destructive yet profitable exploits in mining, drilling, and logging industries (Gudynas 2010) that inherently required on the marginalization of poor women for their implementation.

IV. Analysis of Pink Tide policy: consequences in development and women’s economic autonomy

Neoextractivism, neoliberalism, and failures in general development

Pink Tide nations seemed to have reached a consensus on the selection of extractivism as their primary method for development. The most blatant problem with this is that it fundamentally relies on the marginalization of women and the deterioration of their economic autonomy for its operation (Gudynas 2010; Valencia 2015; Wilkinson 2019). Another issue, on which the next subsection will elaborate, is that Pink Tide administrations did not address preexisting inequalities among men and women before pursuing broader development goals. Lastly, neoextractivism merely continued the pillage and destruction of Latin America that Galeano so poetically chronicled. The monster that Galeano depicts in his work is made up of the same destructive mechanisms that the Pink Tide relied on for its development, both fundamentally (economies still catered to global markets) and literally (destructive extraction methods). “Underdevelopment in Latin America is a consequence of development elsewhere… we Latin Americans are poor because the ground we tread is rich… places privileged by nature have been cursed by history” (Galeano 1997:265).

As we notice the same instruments that oppressed the continent for five hundred years being used to redevelop it, the theories of Audre Lorde begin to materialize: the Pink Tide sought to dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools. As we know from Lorde’s writings, this cannot happen. To relate Lorde’s writings to the context of this paper, “these tools [extractivism] may allow us [Pink Tide nations] to temporarily to beat him [neoliberalism] at his own game, but they will never enable us [Pink Tide nations] to bring about genuine change” (1984:112). With Galeano’s historical review of neoliberalism’s empirical effects and Lorde’s theory on what constitutes authentic and long-lasting development, we can now see how Pink Tide leaders who vowed for the termination of an oppressive institution failed to do so because they preserved oppressive structures from those same institutions. As a result, not only was the Pink Tide inadequate in the overall scope of development but also in its effects on Latin American women’s autonomy.

Additionally, the groundwork for these failures can be attributed to colonial legacies. Sen and Grown state that “the colonial era thus laid the basis for the particular position of Third World countries in the world economy” (1987:30). Consequently, Pink Tide nations suffered from “Dutch disease,” an economics term that refers to a state’s overdependence on one industry and consequent deterioration of other industries’ productivity (Smith 2020). Residual patriarchal ideologies from colonial rule are also a factor in women’s continued impoverishment in Latin America (Sen and Grown 1987). While the continued reliance on neoliberal extraction methods and residual patriarchies may be credited in part to separate imperialist actors, they should not serve as some sort of scapegoat for the faults of the Pink Tide. Sen and Grown also cite “inherent inequality” and the “poverty-creating character of economic and political processes” from within independent Latin American countries as playing a major role in the continued marginalization of women (1987:30). The next section analyzes these inequalities and economic processes as seen in Pink Tide microeconomic policy in the form of labor markets and maternity/paternity leave laws.

Pink Tide labor markets and maternity leave

Now I will begin to analyze the shared trends among Pink Tide Nations detailed at the beginning of Section II of this paper. I will begin by interpreting the seemingly antithetical statistics that show overall poverty and income inequality as having decreased through Pink Tide years, yet at the same time women’s labor force participation rates slowed and the femininity of poverty index increased. As seen in Figure 2, the stagnation in female labor force participation of women raising children five years old or younger rates was horrendously pronounced among poor women as opposed to those in the upper quintiles of income. This is best understood with a careful focus on Diane Elson’s account of labor markets, the reproductive and productive economies, and their implications on women’s economic autonomy. As stated in Section II, women with higher income are able to move much more freely between the productive and reproductive economies than poor women (Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni 2017). This is because high-income women can more readily hire labor from the productive economy than those with less income (i.e. hire caretakers, babysitters, etc). Poor women, on the other hand, are less able to do so; they cannot subvert the reproductive economy as easily and are thus more likely to remain in the reproductive economy. This is the main cause of stagnating labor force participation rates among poor women (Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni 2017). This, coupled with Conditional Cash Transfer programs enacted by Pink Tide nations that reinforced maternalist views on childcare (Orloff 2006), caused an overwhelming decrease in low-income women’s entrance into the productive economy (Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni 2017). This roadblock heavily repressed poor women’s economic autonomy under the Pink Tide.

Massive disparities in maternity and paternity leave laws further damaged women’s economic autonomy. Neither Chile, Venezuela, Brazil, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Argentina, Bolivia, nor Ecuador offered paternity leave in an amount higher than 10 days during their Pink Tide years (Payva 2021). It is also noteworthy that while the ILO provides an 18-week recommendation for maternity leave laws, no such recommendation has ever been published in regard to paternity leave (Payva 2021). The abysmally low amount of paternity leave granted to men strengthens their role as “breadwinners” and women’s role in childcare and domestic work (Payva 2021), further detracting from the ability of poor women to remove themselves from the chains of the reproductive economy.

Circling back: development according to Gita Sen and Caren Grown

Sen and Grown might have predicted the pitfalls of Pink Tide macroeconomic development. Their theories, drafted almost two decades before the Pink Tide was set in motion, outlined the faults and unsustainability of development that ignored existing conditions of gender inequality. As can be seen in the cases presented thus far, Pink Tide domestic policies involving labor markets, gendered maternity/paternity leave allowances, and maternalist CCT programs did just that, propping up harmful gender roles and further restricting the economic autonomy of poor women in particular. In addition to this, broader development goals marginalized this specific intersection of gender and class. The continental leftist movement frequently turned a blind eye to low-income women in their microeconomic and macroeconomic policies, directly opposing Caren Grown and Gita Sen’s critical guideline of taking into account the vantage point of poor, historically oppressed women in policy implementation. Pink Tide neoextractivism, labor markets, and maternity/paternity leave laws all had no such accounts or perspectives. Let this serve as a lesson for the visions of future enterprises and an important support for the practical applications of Sen and Grown’s theories on development.

V. Concluding remarks

The Pink Tide gained momentum from its vibrant reprehension for neoliberal structures and garnered support from broad swaths of their respective populations based on platforms of momentous social and economic change. This considerable ideological shift in Latin American geopolitics gave hope to many impoverished peoples in the early 2000s as distinctive leftist figures began to take charge of Latin America. While it is true that significant portions of the population were climbing out of poverty and experiencing improvements in their general livelihoods under Pink Tide administrations, not all people felt these gains. The methodology of these advancements was unsustainable and carved at the economic autonomy of women and poor women especially; the work of Gita Sen and Caren Grown and the empirical deductions of Eduardo Galeano corroborate these conclusions. Furthermore, labor markets under the Pink Tides created conditions under which poor women were confined to maternal gender roles, locked into the reproductive economy, and deprived of their economic autonomy. Analysis of stagnant labor force participation rates reveals that poor women were disproportionately susceptible to this and were essentially barred from work outside of household duties and childcare. Pink Tide CCT programs, seemingly progressive in nature, served to further marginalize this group at the intersection of gender and class. Looking towards the future, it is paramount that policy implementation strives to work towards either gender equality or broader development focuses on improving the lives of poor women and does not preserve oppressive structures of past oppressors; this paper has conveyed this by applying sociological theory on gender, class, and development to an empirical analysis of the majority of nations that participated in the Pink Tide of the early 2000s.

References

Artiga-Purcell, James. 2021. Contesting Extractivism: Gold, Water and Power in El Salvador. Doctoral dissertation, Philosophy, University of California Santa Cruz.

Careaga, Gloria, Mário Pecheny, and Sonia Corrêa. 2019. “Sexuality in Latin America: Politics at a Crossroad.” Pp. 94-117 in R. Parker, and S. Corrêa (eds.), SexPolitics: Trends and Tensions in the 21st Century – Contextual Undercurrents – Volume 2. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sexuality Policy Watch.

Columbia Law School. 2017. “Kimberlé Crenshaw On Intersectionality, More Than Two Decades Later.” Columbia Law School. https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later

Cornia, Giovanni Andrea. 2010. “Income distribution under Latin America’s new left regimes.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 11(1):85-114.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43(6):1241-1265

ECLAC Gender Equality Observatory. 2012. “Women’s Autonomy: A Closer Look.” Pp. 9-48 in 2012 Annual Report. Santiago: ECLAC

Elson, Diane. 1999. “Labor Markets as Gendered Institutions: Equality, Efficiency and Empowerment Issues.” World Development 27(3):611-627.

Enríquez, Laura J., and Tiffany L. Page. 2018. “The Rise and Fall of the Pink Tide.” Pp. 87-97 in The Routledge Handbook of Latin American Development. Routledge, New York and London.

Filgueira, Fernando, and Juliana Martínez Franzoni. 2017. “The Divergence in Women’s Economic Empowerment: Class and Gender under the Pink Tide.” Social Politics 24(4):370–398.

Galeano, Eduardo. 1997. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Hundred Years of a Pillage of a Continent. New York: Monthly Review Press

Gasparini, Leonardo, and Mariana Marchionni. 2015. Bridging gender gaps? The rise and deceleration of female labor force participation in Latin America: An overview. Work Document 185. La Plata, Argentina: CEDLAS; National University of La Plata. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127701

Humphries, Jane, and Jill Rubery. 1984. “The reconstitution of the supply side of the labour market: The relative autonomy of social reproduction.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 8(4):331-346.

Levitsky, Steven and Kenneth Roberts. 2011. The Resurgence of the Latin American Left. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lind, Amy. 2019. “Foreword.” Pp. ix-xii in E. J. Friedman (ed.), Seeking Rights from the Left: Gender, Sexuality, and the Latin American Pink Tide. Duke University Press, Durham NC.

Lorde, Audre. 1984. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Pp. 110-114 in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

Loureiro, Pedro Mendes. 2018. “Reformism, class conciliation and the pink tide: Material gains and their limits.” Pp. 33-56 in The Social Life of Economic Inequalities in Contemporary Latin America. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Loureiro, Pedro Mendes. 2019. The Ebb and Flow of the Pink Tide: reformist development strategies in Brazil and Argentina. Doctoral dissertation, economics, SOAS University of London.

Lustig, Nora, and Luis F López-Calva. 2010. Declining Inequality In Latin America: A Decade Of Progress?. New York and Washington DC: United Nations Development Programme and Brookings Institution Press.

Moghadam, Valentine. 2005. Globalizing women: Transnational feminist networks. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Morales Hidalgo M. 2020. “A Revolution with a Female Face? Gender Debates and Policies During Rafael Correa’s Government.” Pp. 115-136 in F. Sánchez, S. Pachano (eds.), Assessing the Left Turn in Ecuador. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Orloff, Ann Shola. 2006. “Farewell to maternalism? State policies and mothers’ employment.” Pp. 230-268 in The State after statism. Harvard, CT: Harvard University Press.

Payva, Marisa. 2021. Women do not wear pink in Latin America: A study of the Pink Tide’s controversial legacy in gender equality in South America. Undergraduate thesis, romance languages and classics, Stockholm University.

Picq, Manuela, and María Amelia Viteri. 2019. “No Sexual Revolution on the Left: LGBT Rights in Ecuador.” In P. Gerber (ed.), Worldwide Perspectives on Lesbians, Gays, and Bisexuals: Culture, History and Law 3:26. Santa Barbara: Praeger Press.

Ray, Rebecca, and Sara Kozameh. 2012. “Ecuador’s Economy Since 2007.” In CEPR Reports and Issue Briefs. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Rodríguez Vignoli, Jorge. 2014. “Fecundidad adolescente en América Latina: Una actualización.” [Adolescent Fertility in Latin America: An Update]. Pp. 33-65 in W. Cabella, S. Cavenaghi (eds.), Comportamiento reproductivo y fecundidad en América Latina: Una agenda inconclusa. Rio de Janeiro: ALAP Editora

Sen, Gita, and Caren Grown. 1987. “Gender and Class in Development Experiences.” Pp. 23-49 in Development, Crises and Alternative Visions: Third World Women’s Perspectives. New York: Monthly Review Press

Smith, Edward L. 2020. Neo-Colonialism in Venezuela and its Coverage in Western Media.” Midwestern Marx, September 5. Retrieved December 10 2021 . <https://www.midwesternmarx.com/articles/neo-colonialism-in-venezuela-and-its-coverage-in-western-media-by-edward-liger-smith>

Valencia Vargas, Areli S. 2015. Women and the Deconstruction of the Promise of ‘Inclusive Equality’ in the Context of Extractive-Led Development: The Case of Ecuador. Presentation at the International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, May 29–30

Viteri, Maria Amelia. 2019. “Anti-gender Policies in Latin America: The Case of Ecuador.” In LASA Forum 51:42-46

Wilkinson, Annie. 2019. “Ecuador’s Citizen Revolution 2007–17: A Lost Decade for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality.” Pp. 269-304 in E. J. Friedman (ed.), Seeking Rights from the Left: Gender, Sexuality, and the Latin American Pink Tide. Duke University Press, Durham NC.

.