3 Gender-based violence in Mexico: Intersecting Race and Class – Jocelyn Ruelas

Jocelyn Ruelas

Unpacking Systemic Violence Against Women in Mexico

According to the World Health Organization, the term “Gender-Based Violence” may consist of “emotional, physical, sexual, and /or mental abuse.” (WHO 2018). In 2020 alone, less than 1,000 femicides were reported in Mexico – a rough estimate considering the cases gone unreported (Statista, 2021). To understand the pervasiveness of violence against women in Mexico, is to unpack the layers of social conditioning that permeate every facet of their lives. According to Oxford Dictionary, machismo is one of these layers and is defined as is a “strong or aggressive masculine pride,” often associated with the sexist culture that perpetuates abuse and gendered roles for women across Latin America. I will be analyzing the historical background regarding machismo and how it affects the rates of gender-based violence today.

I also wanted to draw attention to the silenced voices of those in Mexico who could potentially face disproportionate rates of gender-based violence. Afro-descendent and indigenous communities often succumb to higher poverty rates and thus less access to education and healthcare which could correlate to higher rates of gender-based violence. Accessibility to resources can be the difference in saving a life, so I will be analyzing the intersection of gender, race, and class using various frameworks and data to see the correlation, if any, between these variables.

Gender-based Violence and Machismo in Mexico

Ines De La Morena delves into the “diversity of factors” that drives violence against women in their article, “Machismo, Femicides, and Child’s Play: Gender Violence in Mexico (2020). One possible factor is the history of machismo itself, which many believe derive from colonization and early European influence into the Americas. For example, early Mexican laws were generally in consensus with French Civil Code that agreed “women were more well-suited to the domestic sphere as opposed to men who were born to think and act as independent agents,” (De La Morena, 2020). De La Morena highlights the historical ties to modern day attitudes towards women and the importance of recognizing the colonial footprint that is often left out of the conversation. They also mention the present day repercussions of machismo culture, most notably the “double-edged sword” of seeking help from those that “perpetrate violence against them, such as police force and the state (De La Morena, 2020). The systems in place that exist to protect women are more often than not the sites of most violence against them – generating a cycle of abuse and silencing of those courageous enough to speak out.

The Importance of Intersectionality to Understand Gender-Based Violence

In the context of systemic violence lies a deeper understanding of who is being targeted. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color (1991) explores the role of identity politics and the way in which movements can simultaneously benefit and debilitate marginalized groups of people (Crenshaw, 1991:1242). By focusing on one aspect of identity such as race or gender, it creates a sense of tunnel vision that could actually do more harm than good in holistically addressing a complex issue; for example, if one were to trying to fight for racial equity in Mexico, gender should also be considered in dictating who is at most risk considering the institutionalized gendered roles in place. In this manner, the term intersectionality was created to define the ways in which race, class, gender, and sexual orientation are linked and should all be taken into account to analyze the most disenfranchised sectors of society – specifically women of color (Crenshaw, 1991:1242). Crenshaw then structures the framework of intersectionality into three parts: structural, political, and representational to investigate the “broader scope of identity politics” (Crenshaw, 1991:1245).

According to the World Bank on Afro-descendants in Latin America: Toward a Framework of Inclusion, the social inclusion framework is the “process of improving the ability, opportunity, and dignity of excluded groups to take part in society,” (World Bank, 2018:19). Part of this process entails the recognition of intersectional identities and questions “why certain outcomes persist or remain ignored, and why certain groups are overrepresented among the poor or lack equal access to education, health, or job opportunities,” (World Bank, 2018: 19). I will be engaging with this framework to hone in on gender-based violence as it relates to the lived experiences of Afro-Latinas in Mexico. A “multidimensional perspective” will allow me to procure a well rounded understanding of the increased violence faced by Afro-Descendants in Latin America with the inclusion of race and class.

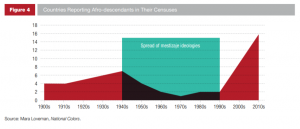

I will also be examining Mara Loveman: National Colors: Racial Classification and the State in Latin America to grasp the underlying racial hierarchy in Latin America. Loveman chronologically breaks down the historical understandings of mestizaje – another way of saying the mixture of races including Indigenous, Spanish, and African ancestry. However, the notion of mestizaje itself implies a preference for and direction towards whiteness, implicitly erasing other identities to support an ideal of homogenization. The negation of racial differences inherently targets these communities of color negatively, especially since they are treated differently based on their phenotypic features. Loveman studies the use of census reports in Latin America as well to reflect the state’s political agenda at the time regarding inclusion and visibility for Indigenous and Afro-descendent communities. Indigenous and Afro-descendent people themselves are taught to believe in this pretense of mixed utopia, yet face the brutal reality of marginalization including language barriers, lack of access to education, healthcare, and voting rights. I will be using this framework to conceptualize how women’s physical autonomy coming from these backgrounds are even more at risk.

The Persistence of Gender-based Violence in Mexico

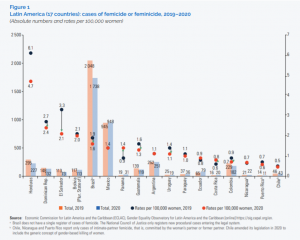

According to ECLAC, the shadow pandemic is a term used by the international community to encapsulate the influx of violence against women amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, the Commission’s Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean (GEO) recorded 4,640 cases of femicide in 24 countries (18 in Latin America and 6 in the Caribbean). In the midst of lockdowns and limited access to resources for women’s autonomy, the staggering death toll is evidence of an ongoing epidemic of targeted violence – heightened by the pandemic.

“According to national surveys from six countries in the region, between 60% and 76% of women (around 2 out of every 3) has been the victim of gender-based violence in distinct areas of their life. In addition, on average, 1 out of every 3 women has been a victim of or is now suffering physical, psychological and/or sexual violence at the hands of a perpetrator who was, or is, her intimate partner, which entails the risk of lethal violence: femicide (ECLAC, 2020).”

The data above gives a general idea of the crisis at hand in Latin America in which women are constantly at risk of experiencing harm at the hands of men, more specifically those in close proximity to them. Not only are they physically afflicted, but psychologically scarred for life if they are lucky enough to survive the assault. According to the WHO, Femicide or feminicide is the “intentional killing of women because they are women (WHO, 2012).” Though there are broader definitions of the term, the outcome is the same. Gender-based violence against women in Latin America is a systemic issue that has only continued to persist over time.

The graph above represents the cases of femicide across Latin America from 2019 to 2020 – at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. For Mexico, there were a total of 945 cases in 2019 only to jump to 948 in 2020. Though it does not have the highest rate of femicide cases across the spectrum, Mexico’s rate has remained stagnant at a high of 1.4 cases per 100,000 women throughout the duration of the pandemic. Keep in mind, however, these numbers come from only reported cases – possibly making the margin of error quite large and cases far higher.

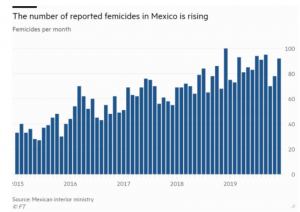

Putting this into perspective from even before the pandemic, the killing of women has been trending upwards since at least 2015 as depicted by the Mexican interior ministry; cases had more than doubled since 2015, increasing at least 145 percent up until 2019 (CFR, 2020). The shadow pandemic is not an isolated issue, only one exacerbated by the passivity of the Mexican government and impunity for perpetrators.

Putting this into perspective from even before the pandemic, the killing of women has been trending upwards since at least 2015 as depicted by the Mexican interior ministry; cases had more than doubled since 2015, increasing at least 145 percent up until 2019 (CFR, 2020). The shadow pandemic is not an isolated issue, only one exacerbated by the passivity of the Mexican government and impunity for perpetrators.

Intersectional Identities Are At Higher Risk of Gender-based Violence

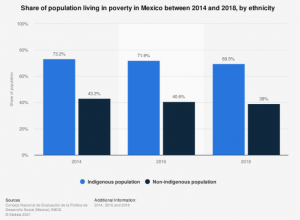

Although making up about 15 percent of the population, indigenous women are often left out of the conversation of femicide (Eagan, 2020). Not only are they more likely to be targeted because of their gender, but their socioeconomic status as well. Since they reside in some of Mexico’s poorest regions, they do not have access to resources that would otherwise save their lives. The data below illustrates the gap between ethnic background and poverty for indigenous and non-indigenous populations in Mexico. Over the span of four years, the correlation is the same – indigenous people are almost twice as likely than non-indigenous people to live below the poverty line, often facing dire circumstances to make ends meet.

The following data builds on this visual representation of the stark contrast between ethnicity and class:

“In 2018, it was estimated that nearly 27.9 percent of the indigenous population in Mexico lived in severe poverty, while only 5.3 percent of the non-indigenous population were considered in the same situation. In total, 8.4 million Mexicans with an indigenous background were estimated to live in poverty (Statista, 2018).”

Therefore, it is more probable that indigenous women living in poverty would not have the means necessary to seek help in violent situations, let alone support themselves financially, in comparison to non-indigenous women.

Indigenous women are also very susceptible to human trafficking, making up 70% of the population of people in Mexico who are taken by cartels year after year (Cultural Survival, 2018). Without proper measures to acknowledge the intersectional nature of violence against women, thousands of women from marginalized backgrounds will continue to go unnoticed and failed by the system.

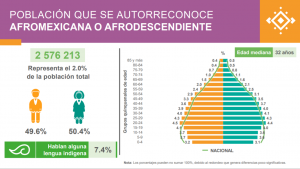

Afro-descendent women in Mexico are also glossed over as victims of Gender-based violence, having to face racism and discrimination on top of the negation of their identity. Only recently have Afro-Mexicans been included in the Mexican census, making up approximately 2.04% of the population (INEGI, 2020). Descending from enslaved Africans during the colonial period, Black Mexicans have existed for hundreds of years – yet have been stripped of their autonomy and identity in a nationally homogenized country.

The infographic above exhibits the Mexican population that self-identifies as an Afro-descendant. This group represents about 2% of the population (around 2,576,213 people total) and 7.4% of this group speak an indigenous language. From the data, it is evident that Afro-Mexicans are alive and present in Mexico.

It was not until 2015 that the Mexican government included Black Mexicans in the census, recognizing their history and existence for the first time from the state itself (INEGI, 2015). Denying African roots exponentially harms the Afro-Mexican community and restricts resources that could essentially save lives.

It is especially difficult to promote change and equity for Afro-descendant women when their identities are weaponized against them; often stereotyped and exoticized for their bodies, Black Mexican women are treated as objects rather than respected individuals in Mexican society. They are boxed into roles of servitude or tools for male consumption that construct their identities around subservience. This social construction of Afro-descendent women is especially harmful since it seeps into every facet of their lives – including basic human rights and protection from the government.

History of Gender-based Violence

To unpack gender-based violence in Mexico is to take a deeper look at the history of machismo and sexist ideals perpetuated in mainstream society. Ines De La Morena dissects the origin of machismo and movements surrounding femicide in Mexico to gain an overarching awareness of the systemic issue at hand.

“Some historians identify La Conquista, during which Spanish colonizers such as Hernán Cortes and his conquistadors arrived in the American continent and raped indigenous women, as the beginning of a culture of gender violence. La Conquista created “mestizos” or people with shared Spanish and indigenous ancestry. Psychologists suggest “mestizaje” creates a condition where mestizos “[envy] their Spanish father and despise their Indian mother (De La Morena, 2020).”

Originating from brutality and a hunger for power, colonization bred an ideology in which the domination of women equated and substantiated superiority. Consequently, machismo was born – creating an internalized necessity among Latino men to maintain control and strength. Femininity, equating to womanhood, was deemed a vice and therefore a threat to masculinity; a threat that must be tamed only by the force of virility.

And yet, the real danger lies in the Mexican government’s inability to shift these inhumane ideals – enabling the murder of countless women whose lives are reduced to a residual afterthought. Ines De La Morena conveys this epidemic by describing the causal relationship between narco politics and gender-based violence; countless times have Mexico’s political authorities turned a blind eye to illegal drug activities for monetary gain. The facade of an effective and energetic state have also escalated violence against women: “Violence is viewed as a sign that the violent actions taken by the government to end narcotrafficking are working (De La Morena, 2020).” The lack of action on behalf of the government has proven to be counterproductive and essentially fatal for many women who fall between the cracks of organized crime.

Failure in the judicial system has been devastatingly cancerous to any form of justice for women. De La Morena emphasizes the impunity that men are granted when prosecuted for their homicidal crimes; “93% of all criminal defendants in cases of gender violence are men” (De La Morena, 2020). More importantly, however, “despite the massive number of potential cases, few women choose to go to the legal system with 98 percent of all gender-related killings, mostly femicides, going completely unprosecuted, (De La Morena, 2020). The hush culture surrounding domestic violence or assault against women in general discourages seeking help, often associating it with weakness for not handling it in the house. Unfortunately, many women do not even make it that far to make that decision for themselves.

Analysis From An Intersectional Lens

Kimberley Crenshaw builds a more comprehensive framework to protect women of color as she recognizes the marginalization of certain intersecting identities.

“Because of their intersectional identity as both women and of color within dis- courses that are shaped to respond to one or the other, women of color are marginalized within both (Crenshaw, 1991:1244).”

By focusing on race and class specifically, Crenshaw emphasizes the need to account for more than just a singular identity to respond to a cause and ensure the safety of those most vulnerable. Splitting her focus into three main issues, Crenshaw draws her conclusions from the following structure: structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality. I will be extracting from her analysis of structural intersectionality.

- Structural Intersectionality

Many of the obstacles women of color face are largely determined by their class and gender struggles on top of being racially discriminated against. For example, WOC are more likely to grapple with “poverty, child care responsibilities, and the lack of job skills,” (Crenshaw, 1991:1245). These issues are exponentially dependent on the dynamics of race, class, and gender because the systems in place like housing practices and employment are not built to support these communities (Crenshaw, 1991:1245). Likewise, Crenshaw also mentions how language barriers are a huge hindrance to accessibility for women of color. Contextualizing the case in Mexico, “Indigenous peoples (10 per cent of the region’s population) were particularly affected by lack of access to information, as they often only understand indigenous languages (UN Women, 2021).” Therefore, it will be even harder for indigenous women to socially, economically, and politically advocate for themselves since they cannot understand the language of the state. If one were escaping domestic violence, for example, they would not be able to receive the best care, let alone any assistance, if the information provided is not in their native language. Their world is a lot smaller when their doors of communication are closed – keeping them confined to abuse.

The ‘Myth of Mestizaje’ and Erasure of Identity

The World Bank’s Afro-descendants in Latin America framework for social inclusion breaks down the financial glass ceilings over the Afro-descendent population across the region. Afro-descendent households are 2.5 times more likely than non-Afro-descendent households to be chronically poor (World Bank, 2018: 77). Even with the evolution of legislation to combat this inequality, institutionalized invisibility of the Afro-descendent population impedes these efforts from ever materializing. The framework aims to deduce the origin of inequity for Afro-descendants and provoke drastic change regarding recognition, respect, and inclusion in the private and public sectors of life. This idea is expressed in the following excerpt:

“In colonial Mexico, black communities exceeded the number of white. But in spite of the large African diaspora, post revolutionary Mexican governments promoted an ideology of mestizaje centered on the glorification of the precolonial, indigenous past, and its contributions to the character and potential for development of modern-day Mexico. Blackness was erased from the Mexican national image, both as a separate racial category and as a component of the mestizo population. These notions persisted throughout the twentieth century and, even in 1996, reports submitted on behalf of the Mexican state to the United Nations claimed that racism was nonexistent in the country and that the majority of the Mexican population was mestizo (indigenous and white mixture) (World Bank, 2018: 44).”

What does this mean for Afro-descendant women? Considering how their history was essentially erased in the name of development, only recently has there been any methodology to make up for years of erasure. Regarded as a population “left behind,” Afro-descendents require “targeted policies” that will elevate their socioeconomic status and narrow the poverty gap. (World Bank, 2018:77). Intersecting poverty with gender further proves that Afro-Mexican women are exceptionally overlooked, often the invisible and most vulnerable victims of gender-based violence.

The framework also highlights what it means to identify with blackness in a vastly narrow minded society, often rejecting any outliers for the sake of homogeneity. Mara Loveman expands on this idea through an in depth chronology of national interests across Latin America.

Following the independence of varying Latin American countries, many political leaders found themselves using “racial democratization” or “mestizaje” as a unifying tool to separate from their colonial past (Loveman, 2014: 232). Because racial mixing was deemed “inevitable,” people were now grouped by culture (mestizo), rather than race to essentially advertise an undivided state (Loveman, 2014: 232). However, according to the Spanish colonial caste system, the term ‘mestizo’ was associated with a close proximity to whiteness.

“Thus, the underlying celebration of mixed national types, the ideological privileging of whiteness, and the tight association of Euro-pean-ness with the very idea of modernity, remained essentially unscathed,” (Loveman, 2014: 232).

So, the disappearance of Indigenous and Afro-descendent representation was a deliberate process that was innately influenced by colonization. Compiling all identities into one without considering the existing social hierarchies in place fostered explicitly racist social norms that kept Afro-descendants and Indigenous communities vulnerable.

Based on the data above, post-race ideologies were fervent between the 1940s and 1990s, nullifying the existence of African identity as a means of consolidating nationalist ideals of the elite (Loveman, 2014: 247). What was once used as a tool for political gain, is now manifested in the present day as a social norm for many. According to the National Survey on Discrimination in Mexico, the results determined that many Mexicans do not perceive skin color to be a strong determinant of prejudice in their lives (Enadis, 2020). Nonetheless, there is clear evidence on racial disparities in Mexico rejecting this notion. Based on Vanderbilt’s Americas Barometer, the relationship between race and education in Mexico reveals a negative correlation between browner skin and education level; lighter Mexicans attended about 10 years of schooling while darker students only averaged to about 6.5 (AmericasBarometer, 2017). Similarly, the wealth gap between lighter and darker Mexicans is distinct, with lighter Mexicans belonging to the 70th percentile of wealth on average and darker Mexicans in the bottom 50 percent (AmericasBarometer, 2017).

Based on the data above, post-race ideologies were fervent between the 1940s and 1990s, nullifying the existence of African identity as a means of consolidating nationalist ideals of the elite (Loveman, 2014: 247). What was once used as a tool for political gain, is now manifested in the present day as a social norm for many. According to the National Survey on Discrimination in Mexico, the results determined that many Mexicans do not perceive skin color to be a strong determinant of prejudice in their lives (Enadis, 2020). Nonetheless, there is clear evidence on racial disparities in Mexico rejecting this notion. Based on Vanderbilt’s Americas Barometer, the relationship between race and education in Mexico reveals a negative correlation between browner skin and education level; lighter Mexicans attended about 10 years of schooling while darker students only averaged to about 6.5 (AmericasBarometer, 2017). Similarly, the wealth gap between lighter and darker Mexicans is distinct, with lighter Mexicans belonging to the 70th percentile of wealth on average and darker Mexicans in the bottom 50 percent (AmericasBarometer, 2017).

Moving Forward

With this in mind, tackling gender-based violence from an intersectional approach will require a cultural revolution – a gradual but effective process of ‘decolonizing the mind.’ Harnessing an understanding of Mexico’s colonial past opens more room for conversations surrounding visibility and recognition of underrepresented communities.

The variables that drive GBV consist of the culture of machismo, impunity for perpetrators, and lack of access to support services. These factors are vinculated by the effectiveness and leadership of the Mexican government; despite many attempts to integrate policy focusing on gender, implementation is lacking and passive attitudes by government leaders stagnate the issue.

Gender-based violence and femicide are ongoing struggles that infect every corner of the globe. Therefore, it is imperative that we garner an integrated approach to protecting those most at risk through an intersectional lens. If we generalize focus onto simply gender, we are not prepared to assess the reality for those marginalized by society – inherently facing violence at much higher rates.

With that being said, I deduced a relationship between gender, race, and class in Mexico – a proud ‘race-blind’ country. Historically disenfranchised groups in Mexico continue to be failed by a system that upholds colonial beliefs regarding race and class – which consequently puts their physical autonomy at a higher risk than mestizas.

With the help of Ines de la Morena, Kimberley Crenshaw, the World Bank, and Mara Loveman, I was able to link the brutalities of Mexican history to the lingering social, economic, and political ramifications of identity.

There is still so much work to be done in not only Mexico, but around the world.

Lack of data available on intersectional gender-based violence is a deadly issue. It is also important to acknowledge the resistance to the status quo and the work that has already been done to shed light on this issue. Hundreds of movements across Latin America have sparked inspiration and gradual change, but there is still tremendous work to be done to shift cultural norms that are used to justify violence against women. It will take time, but it is not impossible.