4 The Fight for Reproductive Justice in Central America: Transnationalizing the Green Tide- Daniela Garcia

dagarcia

In recent decades, there has been growing debate and discourse in Latin America around sexual and reproductive rights. In the socially-conservative and predominantly Catholic region, historically taboo topics such as abortion have gained more visibility, with the emergence of a regional feminist movement in the region that has placed the decriminalization of abortion and an end to violence against women on its agenda. According to UN Women, Latin America is home to 14 of the 25 countries with the highest rates of femicide in the world.[1] Equally concerning is the high rates of sexual violence against women in the region,[2] which has created systemic issues and devastating impacts for survivors in countries where there is a total ban on abortion. Women and feminists in Latin America have been responding to these injustices both at the local and global levels in recent years, mobilizing through mass-demonstrations, shouting slogans in the streets and posting hashtags online, such as #NiUnaMenos (#NotOneLess) and #VivasNosQueremos (#WeWantUsAlive), connecting the movement for women’s safety, health, and autonomy to the fight for reproductive rights and the decriminalization of abortion.[3] These demonstrations have been associated with the color green, earning the name the Green Tide, or the Marea Verde, as images circulated around the world of women standing side by side holding green scarves and signs referencing the need for safe and legal abortion (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1 2017 Demonstration for safe and legal abortion in Argentina

Fig. 1 2017 Demonstration for safe and legal abortion in Argentina

Fotografías Emergentes. “Grito Global por el aborto legal, seguro y gratuito,” 29 Sept, 2017.

The green scarf, or pañuelo verde, has become an emblem of the Latin American feminist struggle for the decriminalization of abortion, and more broadly, for the right to bodily autonomy. The green scarf is a “material artifact.. that represents and facilitates the experiences of mediated togetherness propelling contemporary social movements.”[4] In the streets of major cities around Latin America, such as in Argentina where the movement began, activists have held up their scarves, “greening” public spaces, forging a “uniform presence out of little fragments, leaving the loose end of a green scarf as an open invitation”[5] for alliance and solidarity. The movement’s bold protests and powerful, right-based discourses have visibilized the injustices of abortion’s criminalization in various Latin American countries, putting pressure on governments’ decision-makers to enforce reproductive rights.

Among this emerging Green Tide of feminist activism throughout Latin America, there is a contrast between the realities of women in Central America and the rest of the region, primarily due to the extremely restrictive legal frameworks regarding abortion in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras that contribute to, and exacerbate, trends in maternal mortality, unmet demands for family planning services, rates of adolescent pregnancy, and impediments in accessing comprehensive health services. This paper will look at the case of these three Central American countries to give an overview of the status of reproductive health and rights in this subregion, analyze the impacts of the total criminalization of abortion on the lives of women, and examine responses to reproductive injustices in the context of the Green Tide movement.

Reproductive Justice, Intersectionality, and Transnational Feminist Frameworks: Reproductive Rights as Human Rights

The analysis of the fight for reproductive rights in the Central American subregion, borrows from a variety of interdisciplinary frameworks, including violence frameworks, reproductive justice, intersectionality, and transnational feminist frameworks. The reproductive justice (RJ) framework pre-dates the 1994 Cairo conference and was coined by a group of African American women who organized a women of color feminist collective called SisterSong. The RJ framework is defined as “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”[6] This approach is rooted in intersectionality, a feminist theory spearheaded by Kimberlé Crenshaw, whose analysis of the experiences of women of color in battered women’s shelters argued that the intersection of systemic oppressions that women of color face create structural vulnerability that may further subject them to different forms of violence.[7] Reproductive justice and intersectionality frameworks provide a critical lens through which to analyze the various levels of structural oppression impacting reproductive rights, primarily in the way that social, geographical, racial, and economic marginalization have created disparities in physical autonomy and the agency that women are able to take over their lives and bodies.

A key concept referenced in this work is the 1994 Cairo International Conference on Population and Development’s definition of reproductive rights as “human rights shared by all people,” and which also recognizes “women’s freedom to regulate their fertility safely and effectively, to decide whether or not to have children, when and how often, and to have access to health services that will ensure pregnancy and childbirth are non-threatening.”[8] This broader view of reproductive health not only meant the absence of disease, but redefined reproductive health in a more holistic sense, as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being,”[9] that encompassed the ability to enjoy a satisfactory sex life. Despite the acknowledgement of this holistic concept of reproductive health as human rights by countries who participated in this conference, state policies and cultural perceptions that limit women’s right to reproductive health around the world, and particularly in Central America, continue to deny human rights.

Furthermore, women’s physical autonomy has been a central component of international gender and development discourse as it relates to the advancement of gender equality, reproductive rights, and the obstacles hindering women’s progress. The Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean has identified a set of important areas constituting physical autonomy. These indicators point to obstacles that women in the Latin American region face in “seeking to take their own decisions about their sexuality and reproduction and to exercise their right to a life free of violence,” and include women’s deaths at the hands of their intimate or former partner, maternal mortality, teenage motherhood, and unmet demands for family planning services.[10] Central America as a region experiences high rates of teenage motherhood, which is defined by the Observatory as the percentage of adolescent women between the ages of 15 and 19 who are mothers. Another key issue impeding women’s autonomy in Central America is the unmet demand for family planning services, understood as the “percentage of women who are part of a couple and who do not want to have any more children or who want to delay the birth of their next child but are not using a family planning method.”[11] The Observatory’s indicators of physical autonomy provide an important framework in my analysis of reproductive rights and justice for women in Central America.

In the fight for reproductive rights in the region, a growing transnational feminist movement has emerged in the last few years, symbolized by a green scarf or pañuelo, inspired by the Argentine movement led by the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, in which mothers wore white headscarves as they confronted Argetina’s dictatorship over their missing children. The call for reproductive justice and an end to gendered violence have been two connected, central pillars of the Green Tide movement. While reproductive justice and violence against women may seem to be two separate feminist issues, I agree with feminist reproductive scholars and activists that they are linked, as “reproductive justice cannot be fully achieved and realized until women of color worldwide” are able to live a life free of violence in all social and cultural forms and achieve full social and physical autonomy.[12] This approach builds on understandings of women’s autonomy, as defined by ECLAC, and highlights the links between violence and reproductive (in)justice. This violence is perpetuated by many actors, taking various forms.

These frameworks emphasize that reproductive rights are human rights, and the social, political, and institutional attacks on women’s autonomies are acts of violence that have many implications for women in a variety of spheres. The fight for reproductive justice in Latin America in the contemporary era is being propelled by a growing movement of transnational feminists in the region, who are fighting for an end to gendered violence against women in all forms, with a central struggle being the fight for bodily autonomy and the decriminalization of abortion.

Case Study: The Status of Reproductive Health in Central America and the Criminalization of Abortion

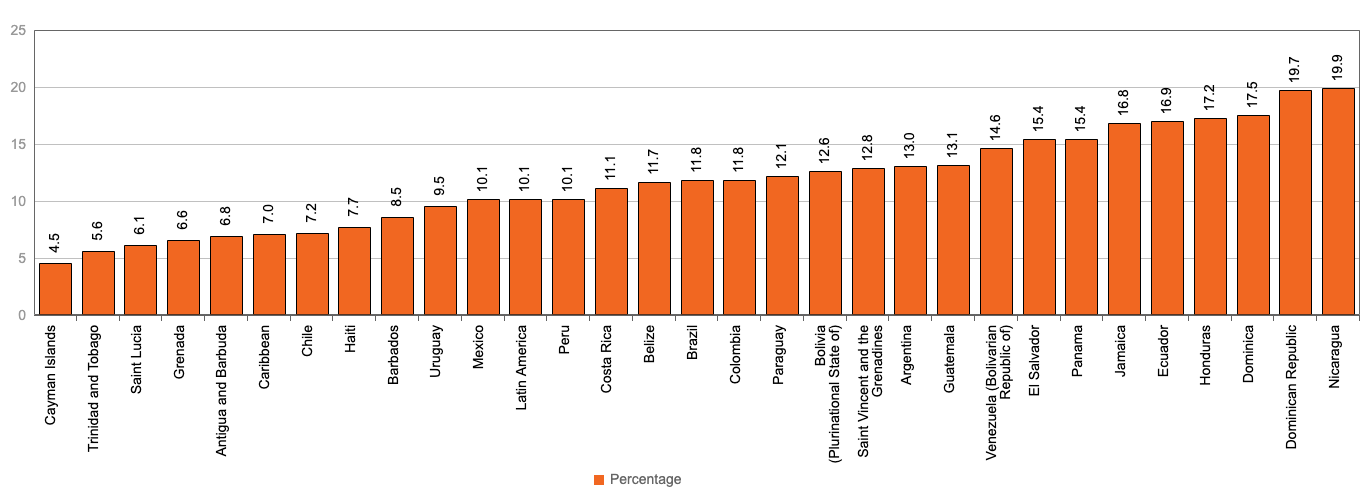

My case study primarily focuses on the status of reproductive health and access to abortion services in Central America, in the countries of El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras. I aim to highlight the impacts of these restrictions on the lives of women and how they exacerbate existing issues in the region related to reproductive health, women’s rights, and development. A 2019 study conducted by the Guttmacher Institute looked at women between the ages of 15-49 in seven countries in Central America to examine the reproductive health needs of the population. From this study, it was reported that 29 million women of reproductive age wanted to avoid a pregnancy, while 5.8 million of them have an unmet need for modern contraception.[13] Among women who wanted to avoid a pregnancy, the unmet need was higher for adolescent women between the ages of 15-19 at 42%, in comparison to all women of reproductive age, who reported 20% of the unmet need.[14] By country, Nicaragua demonstrated a 7.5% unmet demand for family planning services in 2007, El Salvador a 8.9% demand in 2003, and Honduras a 16.8% demand in 2006.[15] In addition, the high rate of adolescent pregnancy is another issue in the region, often referred to as an epidemic of adolescent pregnancy, which has demonstrated disparities in terms of income and education levels.[16] As demonstrated in Figure 2, Nicaragua leads the entire Latin American region at 19.9% of adolescent women, followed by Honduras at 17.2%, and El Salvador at 15.4%.[17]

Fig. 2 Teenage Maternity in Latin America and the Caribbean and the Iberian Peninsula from ECLAC, latest data available per country.

(https://oig.cepal.org/en/indicators/teenage-maternity)

The rate of maternal mortality is another important indicator of reproductive health. In a study conducted by ECLAC and the WHO about trends in maternal mortality in the region, per 100,000 live births, Honduras had a maternal mortality rate of 120, El Salvador a rate of 81, and Nicaragua a rate of 95.[18] The link between access to abortion and maternal mortality is clear, the criminalization of abortion will lead to clandestine procedures with many health risks. El Salvador has one of the most restrictive legal frameworks regarding abortion in the region. Since 1998, “access to abortion has been criminalized under all circumstances”[19] including in the case of rape and obstetric emergencies. In 1999, the Political Constitution was amended to recognize “every human being from the moment of conception”[20] as a person. Between 2000 and 2019, there were 181 cases of women who were criminally prosecuted for abortion or aggravated homicide for experiencing obstetric emergencies.[21] This crime can be punished with up to 50 years in prison. Like El Salvador, Nicaragua adopted a penal code in 2006 which completely banned abortion, “even in cases of rape, incest, life- or health-threatening pregnancies, or severe fetal impairment.”[22] In 2008, a legal challenge submitted to the Supreme Court argued that this ban was unconstitutional, however the Supreme Court never ruled on this case, nor on a similar case about the 2014 constitution.[23] Following the precedent set by Nicaragua and in El Salvador in the Central American region, Honduras has a blanket ban on abortion, which has been constitutionally banned since 1982, even in the case of rape, incest, or in the case of danger to the mother or fetus.[24] Furthermore, Honduras is the only country in Latin America where emergency contraception is banned.

Analyzing the Impacts of Reproductive Injustices in Central America: Lessons from The Green Tide

From the research gathered, four key issues related to reproductive rights are identified: high rates of sexual violence against women, high demand for family planning services, the lack of access to comprehensive health services, and the epidemic of adolescent pregnancy in the Central American region. These factors do not guarantee the right to health and impede social and economic development.[25] Resources that ensure the holistic well-being of women and allow them to make informed decisions about their sex lives and reproduction are necessary to prevent adolescent pregnancy and ensure reproductive health. The alarming patterns of sexual violence against women and limited access to sexual and reproductive health services means that women and girls are frequently forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term, creating further negative impact on girls’ mental, physical, and social health.[26] This leaves them vulnerable to higher risks of maternal mortality, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide. For young and teenage mothers, this could also lead to early or forced unions.[27]

A key strategy in pro-choice advocacy in the subregion has been the use of international human rights law by international NGO’s and activist groups to denounce the human rights violations occuring in the prosecution of women who have had obstetric emergencies or terminated pregnancies. In 2014, Center for Reproductive Rights and the Agrupación Ciudadana por la Despenalización del Aborto Terapéutico, Ético y Eugenésico in El Salvador published report titled “Marginalized, Persecuted, and Imprisoned: The Effects of El Salvador’s Total Criminalization of Abortion,” using a human rights perspective to document and reveal the consequences of El Salvador’s total abortion ban on the lives of women, particularly giving voice to women who were “wrongly prosecuted for abortion-related crimes after suffering obstetric emergencies in the absence of medical attention.”[28] One particular testimony is the case of María, who was 18 years old and finishing her last year of high school when she became pregnant.[29] In June of 2009, María began to experience medical complications for two days, including intense pain, fainting spells, and hemorrhaging. When it became clear that María needed medical attention, she visited a private doctor who informed her of her pregnancy for the first time; she had suffered a miscarriage and was told that she needed to run further tests at a public hospital. Despite never knowing she was pregnant before the obstetric emergency; she was accused of having induced the miscarriage and was threatened with arrest. After being treated for 15 days at the San Bartolo National Hospital, she was released on July 7, 2009, and immediately arrested by the police for allegedly having committed murder, an arrest based on a criminal complaint filed by the hospital’s social worker.[30] María’s story is just one example of the impact that El Salvador’s blanket ban on abortion has on women’s lives. What began as a young woman seeking urgent medical attention resulted in a punitive and traumatizing criminal investigation, leading to detainment that worsened María’s medical condition and wrongly persecuted her on claims that her obstetric emergency was an effort to intentionally abort. The risk of criminal prosecution may defer women in the subregion from seeking essential health care services, and has further impacts on the health, legal, and prison systems, as health professionals who treat women facing obstetric emergencies “believe that they are legally obligated to report their patients to the police in order to avoid criminal prosecution.”[31] Furthermore, the criminal proceedings taking place often do not give women experiencing obstetric emergencies or terminated pregnancies the presumption of innocence, playing on gender stereotypes, such as the “immoral woman” or the stereotype “according to which the highest purpose of a woman is sacrificing herself in the name of reproduction.”[32] Despite the total ban on abortion, an estimated 246,275 abortions took place between 1995 and 2000 in El Salvador, out of which 11.1% of them resulted in the death of the pregnant woman; while 19,290 abortions occurred between January 2005 and December 2008, 27.6% of which were on adolescents.[33]

El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras’ total ban on abortion is rooted in the deep cultural and religious influences that exert power over the politics dictating women’s lives. While decriminalizing abortion is not enough to fully address the scope of reproductive rights issues in Central America, it is a crucial aspect of ensuring women’s physical autonomy and allowing women to make decisions about their bodies and lives. The inability of women and girls to obtain safe and legal abortion care violates the following rights: life; integrity; health; freedom from torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment; freedom from discrimination; the right of girls to be heard on matters that affect them; and the right to a private life.[34] Many rights groups have reprimanded the criminalization of abortion, due to its violation of human rights and the disproportionate impact on young women, ethnically and racially marginalized groups, rural women, women with disabilities, and women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.[35] While privileged sectors of women, like those with the financial resources, can go to private clinics to have these procedures done without risking imprisonment, women who are usually convicted for murder or other charges are the ones “who could not afford an expensive hospital to end their pregnancies,” pointing to the issue that “strict abortion laws in Latin America criminalize poverty.”[36] There is a need for the legal decriminalization of abortion, but also the need to “socially decriminalize” abortion in order to address the cultural and religious attitudes that create this status-quo in the first place.

These are among the primary issues that Latin America’s “Green Tide” has been pushing forward. Mass protests in countries like Argentina have called for an end to violence against women and the decriminalization of abortion, creating dialogue and placing the once-taboo subject of abortion on the national agenda. These mobilizations have successfully created much needed reforms, as in the case of Argentina, where the termination of pregnancy within the first fourteen weeks in January of 2021 was legalized, greatly due to feminist activism.[37] These mass-mobilizations have visibilized the struggle for legal and safe abortions on demand, diffusing strategies of resistance in the Latin American region and beyond. However, in the case of Central America, cultural, religious, and political opposition makes the possibility of reform difficult. While the Green Tide movement has created a sense of urgency and hope for Latin American feminists, Central American feminists face a particular set of challenges, calling for an awarness of “adverse antidemocratic contexts with authoritarian and machista governments,” coupled with the absence of secular states and their public policies marked by religious fundamentalisms.[38] Central American feminists have noted the intense structural violence and injustice women face in their countries as the context from which their own movements to decriminalize abortion emerge.[39] However, they also echo a sense of empowerment gained from the Green Tide movement, a commitment to fight in solidarity with feminists in other countries, seeing their struggle as not just national ones, but as interconnected: a transnational, regional struggle.[40]

The diffusion of the Green Tide movement brings new hopes and poses new challenges for feminists in Central America, who must confront the social, religious, and political obstacles as they challenge oppressive structures and push abortion reform in their respective countries. Perhaps a key opening in this subregional struggle for reproductive rights is the recent election of Honduras’ first woman president, Xiomara Castro, who has pledged to ease the country’s strict abortion ban and allow the use and distribution of emergency contraceptive pills, with strong conservative opposition expected.[41] Reproductive rights in Central America are not only contingent on the legal decriminalization of abortion, but on its social decriminalization as well. Ensuring reproductive justice in Central America is an extensive project that does not end with the decriminalization of abortion. However, safe, legal, and accessible abortion on demand is crucial right that may ameliorate the racial, economic, and social disparities that criminalizing abortion creates. As Latin American feminists of the Green Tide are demanding, “¡Que sea ley!” (Let it be law!).

Endnotes

[1] United Nations Women, “Supporting Rural and Indigenous Women in Argentina as Gender-Based Violence Rises during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” October 12, 2021. Para. 4.

[2] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Annual Report 2012 A Look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women” (NY, NY: United Nations Publications, 2012), 3.

[3] Marcela A Fuentes, in Performance Constellations: Networks of Protest and Activism In Latin America (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2019), 110.

[4] Fuentes, Performance Constellations: Networks of Protest and Activism In Latin America, 110.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Leandra Hinojosa Hernández and Upton Sarah De Los Santos, Challenging Reproductive Control and Gendered Violence in the Americas: Intersectionality, Power, and Struggles for Rights (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018), 10.

[7] Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (July 1991): pp. 1241-1300.

[8] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Annual Report 2012 A Look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women” (NY, NY: United Nations Publications, 2012), 3.

[9] UN Population Fund, “International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action” (NY, NY: UN Population Fund, 1995), 40.

[10] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Annual Report 2012 A Look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women” (NY, NY: United Nations Publications, 2012), 10.

[11] Ibid. 19.

[12] Leandra Hinojosa Hernández and Upton Sarah De Los Santos, Challenging Reproductive Control and Gendered Violence in the Americas: Intersectionality, Power, and Struggles for Rights (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018), 18.

[13] Sully EA et. al. Adding It Up: Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health in Central America. NY, NY: Guttmacher Institute, 2020.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Annual Report 2012 A Look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women” (NY, NY: United Nations Publications, 2012), 22.

[16] Ibid. 20.

[17] Ibid. 19.

[18] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Annual Report 2012 A Look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women” (NY, NY: United Nations Publications, 2012), 18.

[19] Center for Reproductive Rights et. al “Manuela v. El Salvador: The Impact of Blanket Abortion Bans on Women Experiencing Obstetric Emergencies.” March 21, 2012. 1.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “Nicaragua: Abortion Ban Threatens Health and Lives,” Human Rights Watch, July 31, 2017.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “Honduran Abortion Law: Congress Moves to Set Total Ban ‘in Stone’,” BBC News (BBC, January 22, 2021).

[25] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Annual Report 2012 A Look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women” (NY, NY: United Nations Publications, 2012), 9-10.

[26] “They Are Girls: Reproductive Rights Violations in Latin America and the Caribbean” (Center For Reproductive Rights, 2019). 1.

[27] Towards Parity and Inclusive Participation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional Overview and Contributions to CSW65. UN Women, 2021. 36.

[28] “Marginalized, Persecuted, and Imprisoned: The Effects of El Salvador’s Total Criminalization of Abortion” (The Center for Reproductive Rights, Agrupación Ciudadana, 2014). 8.

[29] Ibid. 11.

[30] Ibid. 26.

[31] “Marginalized, Persecuted, and Imprisoned: The Effects of El Salvador’s Total Criminalization of Abortion” (The Center for Reproductive Rights, Agrupación Ciudadana, 2014). 8.

[32] Center for Reproductive Rights et. al “Manuela v. El Salvador: The Impact of Blanket Abortion Bans on Women Experiencing Obstetric Emergencies.” March 21, 2012. 5.

[33] “Marginalized, Persecuted, and Imprisoned” (The Center for Reproductive Rights, Agrupación Ciudadana, 2014). 10.

[34] “They Are Girls: Reproductive Rights Violations in Latin America and the Caribbean” (Center For Reproductive Rights, 2019). 1.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Trogneux, Wendolyn. Rep. Inadequate Reproductive Rights in Latin America. Global Policy Review, 2020. 4.

[37] Towards Parity and Inclusive Participation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional Overview and Contributions to CSW65. UN Women, 2021. 36.

[38] Maryórit Guevara, “Discusión De Aborto Legal En Argentina Contagia De Esperanza a Feministas De Centroamérica,” Articulo 66, August 8, 2018.

[39] CISPES, “100 Days of Nayib Bukele in El Salvador: Social Movement Perspectives (Interview),” Nacla, September 9, 2019.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Anne-Catherine Brigada, “Analysis: In Honduras, First Woman President Faces Tough Fight on Abortion,” Reuters, December 8, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/honduras-first-woman-president-faces-tough-fight-abortion-2021-12-08/.

Bibliography

Brigada, Anne-Catherine. “Analysis: In Honduras, First Woman President Faces Tough Fight on Abortion.” Reuters, December 8, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/honduras-first-woman-president-faces-tough-fight-abortion-2021-12-08/.

CISPES. “100 Days of Nayib Bukele in El Salvador: Social Movement Perspectives (Interview).” Nacla, September 9, 2019. www.nacla.org/news/2019/09/06/100-days-nayib-bukele-el-salvador-social-movement.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (July 1991): 1241–1300.

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Rep. Annual Report 2012 A Look at Grants: Support and Burden for Women. NY, NY: United Nations Publications, 2012.

Fuentes, Marcela A. Conclusion. In Performance Constellations: Networks of Protest and Activism In Latin America. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2019.

Guevara, Maryórit. “Discusión De Aborto Legal En Argentina Contagia De Esperanza a Feministas De Centroamérica.” Articulo 66, August 8, 2018. www.articulo66.com/2018/08/08/aborto-legal-argentina-contagia-esperanza-feministas-centroamerica/.

Hernández, Leandra Hinojosa, and Upton Sarah De Los Santos. Challenging Reproductive Control and Gendered Violence in the Americas: Intersectionality, Power, and Struggles for Rights. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018.

“Honduran Abortion Law: Congress Moves to Set Total Ban ‘in Stone’.” BBC News. BBC, January 22, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-55764195.

Publication. Manuela v. El Salvador: The Impact of Blanket Abortion Bans on Women Experiencing Obstetric Emergencies. Center for Reproductive Rights et. al, March 21, 2012.

Publication. Marginalized, Persecuted, and Imprisoned: The Effects of El Salvador’s Total Criminalization of Abortion. The Center for Reproductive Rights, Agrupación Ciudadana, 2014. https://reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/documents/El-Salvador-CriminalizationOfAbortion-Report.pdf.

“Nicaragua: Abortion Ban Threatens Health and Lives.” Human Rights Watch, July 31, 2017. www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/31/nicaragua-abortion-ban-threatens-health-and-lives#.

Publication. They Are Girls: Reproductive Rights Violations in Latin America and the Caribbean. Center For Reproductive Rights, 2019.

Sully EA et. al. Adding It Up: Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health in Central America. NY, NY: Guttmacher Institute, 2020.

Towards Parity and Inclusive Participation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional Overview and Contributions to CSW65. UN Women, 2021.

Trogneux, Wendolyn. Rep. Inadequate Reproductive Rights in Latin America. Global Policy Review, 2020.

UN Population Fund. Rep. International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action. NY, NY: UN Population Fund, 1995.

United Nations Women. “UN Women News,” October 12, 2021. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2021/10/feature-supporting-rural-women-in-argentina-as-gender-based-violence-rises.