5 Cyberfeminism in Latin America in the fight for reproductive rights- Angela Molina

Angela Molina

Cyb∈rF∈miηiςm iη L∀tiη Αm∈ricα iη the Figh† fΘr ℜ∈prΘdu⊂†iv∈ ℜigh†ζ

Angela Molina

Gender and Development in Latin America

Profe. Esther Hernandez-Medina

December 17, 2021

Introduction

Ever heard of a clandestine abortion? In countries where abortion is banned and criminalized, women are pushed to induce their abortion in unsafe manners. For instance, Melina, who lives in Dominican Republic where abortion is criminalized, had to carry out an induced abortion because she could not support another child on top of the four children she already had (Human Rights Watch 2018). She turned to a tea remedy made of herbs and plants that would induce an abortion. Her health declined rapidly after she took it; she started bleeding and felt a great deal of pain in her back and abdomen. After going to the hospital, doctors told her the abortion was incomplete putting her at risk for serious complications in her health. Melina came close to death, and she is one of the many stories of the women in Latin America who live in countries with punitive abortion laws. With high abortion rates, that is not counting the ones that are done in secret, people in Latin America have protested for reproductive rights, I will be specifically looking over the ban on abortion. One of the ways people have done that is through the internet and use of social media platforms.

Feminists who advocate for an expansion on reproductive rights utilize cyberfeminism in different ways to resist the government’s laws that are unjust. An integral piece of literature to understand cyberfeminism is A Cyborg Manifesto, written by Donna J. Haraway. She describes the cyborg as a

“Cybernetic organism, a hybrid machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world changing fiction”

The cyborg is fluid in its nature as it is a machine and organism. Living and nonliving. Feminists have applied her literature to the work they do in cyberspace.

An Overview of Women in Technology

To understand who utilizes the internet and for what reason, one would need to look at the history of how internet use has become gendered. The creation of the internet was a collaboration between American universities and the Pentagon, so it has roots in the military industrial complex. Through feminist criticism, this automatically makes the origin of the internet one that is “deeply embedded in masculine codes and values (Zoonen 2002: 6).” Although the origins of the internet came from “masculine codes”, it had not been gendered until later. Initially, technology had not been gendered, but since technology reflects different social contexts and the way society is structured (Dixon et al. 2014), it is no surprise the type of person who would use the internet more frequently would be male. Going along that vein, a person would need the time, money, and resources to access the internet. To be more specific, the internet was “characterized as a primarily White, male domain, used by those in privileged positions in academia, government, and the military” (Royal 2008). Access to the technology comes easier to the populations who are privileged enough to have the means to buy a computer or a cellphone that has access to the internet. For women, the barriers they face inhibit their participation in cyberspaces. Examples of those barriers include time, money, confidence in their ability to navigate a computer, and negative experiences on the internet (Goulding and Spacey 2003). Women are generally paid less in society, so they lack the financial resources to buy any device with access to the internet. Married or not, women lack the time to access the internet. Women also work more paid/unpaid domestic and time-consuming jobs along with the domestic work they have to do at home. Also, it is important to note “women do not view using the internet as a leisure pursuit as men do” (2003, pg 35). This can be attributed to their lack of confidence when using a computer. Men are more likely to browse the internet, but women feel themselves unable to effectively navigate their way around it (2003, pg 35). This can be attributed to the stereotype that men are more likely to maneuver technology better. This, again, shows how technology can reflect inequalities in society, and even aggravate them. Adding to that, the misogyny and sexism experienced by women is also experienced in online spaces. Women experiencing online harassment by men lead to a decrease of female participation (2003, pg 36).

With all that being said, even what people interact with online can influence their participation. For example, lead internet stories by big new companies are dominated by males so this resulted in female political figures being portrayed in news articles with gender biases (Bruke and Mazarella, 2010). The news articles themselves became gendered. Because men have positions of power on the internet, this can lead internet spaces to be breeding grounds for misogyny online. These cycles can be endless and perpetuate the sexism women face online. To add on, women’s sites were more home and family oriented whereas men’s were business, sports, and dating oriented (Royal 2008; 157). Again, what a woman interacts with online is based on gender stereotypes, and the internet exacerbates it. On top of the less online presence women have compared to men, they feel unwelcomed to appropriate technology as much as men.

Introduction to A Feminist Internet

Although the internet has been male dominated for a while, there is hope. The last framework I will be mentioning is Cyberfeminism and its contribution to the offline feminist movement. Cyberfeminism emphasizes “feminism for the internet and not feminism on the internet” (Manos and Silva 2017). This digital activism is backed by feminists who try to use the male-dominated internet and turn it into a space for feminists to come together and create community. The use of the internet is still recent, but feminists have established their presence in web spaces, more specifically on social media platforms and through the famous lifestyle blog-posting. Feminists even have principles they created to make their online presence meaningful for the movement. They establish their vision for a feminist internet through their principles which ultimately expose what they value. This is very vital to sustain a long-term social movement online. The internet is vast and expansive. Over millions of people partake in cyberspaces, so it is very important to lay a common understanding of what constitutes a feminist internet and what it entails

- A feminist internet starts with and works towards empowering women and queer persons- in all our diversities- to dismantle patriarchy. This includes universal, affordable, unfettered, unconditional and equal access to the internet

- A feminist Internet is an extension, reflection and continuum of our movements and resistance in other spaces, public and private. Our agency lies in us deciding as individuals and collectives what aspects of our lives to politicize

- The internet is a transformative public and political space. It facilitates new forms of citizenship that enable individuals to claim, construct, and express ourselves, genders, sexualities. This includes connecting across territories, demanding accountability and transparency, and significant opportunities for feminist movement-building.

- Violence online and tech-related violence are part of the continuum of gender-based violence. The misogynistic attacks, threats, intimidation, and policing experienced by women and queers LGBTQI people are real, harmful, and alarming. It is our collective responsibility as different internet stakeholders to prevent, respond to, and resist this violence.

- There is a need to resist the religious right, along with other extremist forces, and the state, in monopolizing their claim over morality in silencing feminist voices at national and international levels. We must claim the power of the internet to amplify alternative and diverse narratives of women’s lived realities.

- As feminist activists, we believe in challenging the patriarchal spaces that currently control the internet and putting more feminists and queers LGBTQI people at the decision-making tables. We believe in democratizing the legislation and regulation of the internet as well as diffusing ownership and power of global and local networks.

- Feminist interrogation of the neoliberal capitalist logic that drives the internet is critical to destabilize, dismantle, and create alternative forms of economic power that are grounded on principles of the collective, solidarity, and openness.

- As feminist activists, we are politically committed to creating and experimenting with technology utilizing open-source tools and platforms. Promoting, disseminating, and sharing knowledge about the use of such tools is central to our praxis.

- The internet’s role in enabling access to critical information – including on health, pleasure, and risks – to communities, cultural expression, and conversation is essential, and must be supported and protected.

- Surveillance by default is the tool of patriarchy to control and restrict rights both online and offline. The right to privacy and to exercise full control over our own data is a critical principle for a safer, open internet for all. Equal attention needs to be paid to surveillance practices by individuals against each other, as well as the private sector and non-state actors, in addition to the state.

- Everyone has the right to be forgotten on the internet. This includes being able to access all our personal data and information online, and to be able to exercise control over, including knowing who has access to them and under what conditions, and being able to delete them forever. However, this right needs to be balanced against the right to access public information, transparency and accountability.

- It is our inalienable right to choose, express, and experiment with our diverse sexualities on the internet. Anonymity enables this.

- We strongly object to the efforts of state and non-state actors to control, regulate and restrict the sexual lives of consenting people and how this is expressed and practiced on the internet. We recognize this as part of the larger political project of moral policing, censorship and hierarchization of citizenship and rights.

- We recognize our role as feminists and internet rights advocates in securing a safe, healthy, and informative internet for children and young people. This includes promoting digital and social safety practices. At the same time, we acknowledge children’s rights to healthy development, which includes access to positive information about sexuality at critical times in their development. We believe in including the voices and experiences of young people in the decisions made about harmful content.

- We recognize that the issue of pornography online is a human rights and labor issue, and has to do with agency, consent, autonomy, and choice. We reject simple causal linkages made between consumption of pornographic content and violence against women. We also reject the umbrella term of pornographic content labeled to any sexuality content such as educational material, SOGIE (sexual orientation, gender identity and expression) content, and expression related to women’s sexuality.

Furthermore, cyberfeminism is a mechanism to impede misogyny online. Cyberfeminism can be limitless and fluid, and Sandra Alvarez Ramirez utilizes its philosophy in her blogging. In her blogs, Negra cubana tenía que ser/ AfroCubana had to be, are written with the perspective of being an AfroCubana. Sierra-Rivera states the online space helps form a Black feminist community that uplifts and advocates for Black women. Race and gender are often overlooked in Latin America, but the community Alvarez Ramirez creates emphasizes intersectionality by centering her race and gender in the blog posts. Through her use of cyberfeminism, the intersections of her identity are recognized and put at the forefront. In Hawthorne and Kleins’ words, “Cyberfeminism is political, it is not an excuse for inaction in the real world, and it is inclusive and respectful of the many cultures which women inhabit” (20, pg3). Cyberfeminism can break barriers and create accessible spaces online to combat misogyny. Cyberfeminism is also changing and molding to whatever is needed for the feminist movement, at the time. The use of “new technologies and communications technologies [are] for empowerment” (pg 3). By this logic, it impedes the male-dominated internet that often overlooks race, gender, and class.

The Fight for Reproductive Rights in Latin America

Moving on, I will be using the lens of ECLAC’s (2020) definition of physical autonomy to understand how important it is to center women’s’ decision to abort or not in discourse. It is one of the three dimensions ECLAC proposes to understand women’s autonomy and is “the capacity to freely decide on issues of sexuality and reproduction, and the right to live a life free of violence”. Latin America and the Caribbean are known to have the most restrictive laws on abortion. This can be very dangerous towards the women who live in the countries that ban abortion. I will start by mentioning the punitive laws in various countries in Latin America, then explain why it is dangerous and violent against women. “More than 97% of women of reproductive age in Latin America and the Caribbean live in countries with restrictive abortion laws” (Abortion in Latin America and the Caribbean 2018). The countries “El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, and Suriname completely illegalized abortion. In El Salvador, women are imprisoned even if they are speculated to have had an abortion. In Guatemala, abortion is only allowed when it threatens immediate death for the woman. In Ecuador and Peru, abortions are legal but there are barriers that hinder women from accessing them (Center for Reproductive Rights 2019). Even in a context where women are allowed to carry out an abortion, they are still unable to obtain it because they have inadequate access to the abortion services. Women forced to keep unwanted pregnancies can lead to very detrimental effects. In 2010-2014, an estimated “6.5 million induced abortions occurred each year in Latin America”, and about 1 in 4 abortions in Latin America and the Caribbean were safe (Abortion in Latin America and the Caribbean 2018). This serves as an estimate of how many illegal abortions are happening each year as a cause of the criminalization of it. Many women turn to unsafe clandestine ways to induce their abortion. Paxman et. al (2021) even calls it a “clandestine epidemic” in Latin America that has been ongoing for the past 30 years. The induced abortions can be seriously fatal for anyone who decides to do it. Abortions are going to keep happening regardless of governments’ criminalization of it. That is why it is important to ensure women have access to safe abortions to prevent the loss of their life. “Poor and rural women are the most likely to experience unsafe abortion and severe complications thereof” (2018). This paints reproductive rights issues as race, gender, and class issues, too. Women do not have the financial means to support a child, so they turn to terminating the pregnancy. Populations disproportionately affected by abortion laws do not have the resources to sustain a child’s life, but countries in Latin America continue with the criminalization of abortion.

Ni Una Menos: Social Media and Internet Presence

The first collective I want to highlight is the Ni Una Menos group in Argentina. The name directly translates to “Not one [woman] less”, which alludes to femicides in Argentina. The origin of their name is the phrase, “Ni Una Muerta Mas/ Not One More [Woman] Dead”, created by activist Susana Chavez in opposition to the femicides in Mexico (M1, 2015). This collective has gained transnational support as they demand congress to legalize abortion, along with other feminist issues they advocate for. They are also known for their social media/internet presence. They have “grown into a powerful international women’s movement that describes itself as ‘a collective cry against gender violence’ (Culture Trip, 2017). The catalyst for one of the massive protests they first held was for the murder of Chiara Páez, a 14-year-old who was pregnant. She wanted to keep the baby, but her boyfriend did not so he beat her to death (Diaz, 2021. The movement went on to protest femicides that were happening in the country around 2015. On their website they describe who they are:

“Ni una menos nació ante el hartazgo por la violencia machista, que tiene su punto más cruel en el femicidio. Se nombró así, sencillamente, diciendo basta de un modo que a todas y todos conmovió: “ni una menos” es la manera de sentenciar que es inaceptable seguir contando mujeres asesinadas por el hecho de ser mujeres o cuerpos disidentes y para señalar cuál es el objeto de esa violencia./Not one less was born out of exhaustion from sexist violence, which has its cruelest point in femicide. It was named that way, simply, saying enough in a way that moved everyone: “not one less” is the way of declaring that it is unacceptable to continue counting women murdered because they are women or dissident bodies and to indicate which is the object of that violence (2017).”

There were multiple reasons that catalyzed the movement, but they all held the same exhaustion for the violence women experience

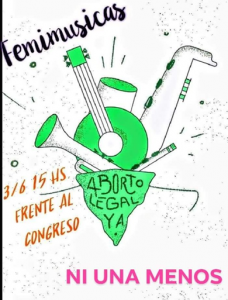

The Ni Una Menos collective utilizes social media and internet spaces to advocate for reproductive rights. They created their twitter account in May of 2015. They use the platform to upload videos and posters of events rallying people to go to “La puerta de congreso” and demand the legalization of abortion.

The twitter account not only uploaded posters for rally events, but videos of different health care workers who advocate for legal abortion, sex education, and reproductive health in Argentina. The collective posted over 20 videos with different health care workers whose job occupations include doctors, psychologists, gynecologists, sexual health educators, surgeons, ermentologists, geneticists, and many others. In these videos, they share their testimonies in support for legal abortions. From the perspective as health care workers, they explain how dangerous clandestine abortions can be for women because abortion is banned and criminalized. They recognize the women who decide to get an abortion are women who cannot sustain themselves economically or do not have the means and resources to support a child. Maria Flavia Del Rosso, a female doctor, states in her testimony, “Las mujeres interrumpimos nuestras gestaciones, independientemente de que sea legal o no, a lo largo del mundo y de las épocas. La legalidad ha demostrado ser lo que marca la diferencia entre la vida y la muerte/ The women interrupt their pregnancies, regardless of if it is legal or not, throughout the world and ages. Legalizing abortion has proven to be the difference between life and death”.

Another quote by Enrique Meza, an obstetrician, states “Las mujeres abortaron, abortan y abortarán, La diferencia es que con atención segura no va a haber muertes / Women have aborted and will abort. The difference is they will not die with safe medical attention.” Lastly, a male doctor stated “Las mujeres se autodeterminan y abortan. Como trabajadores de salud y garantes de derechos tenemos que responder a esas demandas/ Women determine themselves and decide to abort. As health care workers and – we need to respond to those demands.” The rest of the videos echo the same sentiments from these health care workers. Besides the tweets of videos, they also tweet their opinions on abortion with the hashtag #Abortolegalya/#Legalabortionnow.

One tweet states, “Educación sexual para decidir, anticonceptivos para no abortar, aborto legal para no morir/Sexual education to decide, contraceptives to not abort, and legal abortion to not die.” Another tweet says “Las mujeres estamos reclamando por nuestro derecho a la vida y a la salud/ Women are reclaiming our right to live and to health”. In a tweet posted before that, it reads “El aborto clandestino puede provocar secuelas físicas y psicológicas y, en muchos casos, deriva en la muerte de la mujer que se somete al aborto/ Clandestine abortions can provoke physical and psychological effects and, in a lot of cases, result in the death of the women who undergo the abortion.” The Ni Una Menos collective emphasizes how important it is for there to

be accessible and legal abortions. They also recognize women will still have abortions regardless of the criminalization and bans put on it. Majority of their tweets contain the subject of legal abortion, access to sexual education and reproductive health. This exhibits the purpose of their movement and the values they stand for in the fight for reproductive rights in Argentina. Ni Una Menos also has a website with resources, pertaining to abortion, for people to obtain. On the website, there is a tab labeled “Abort Lines” with links to pages with the titles “Network Lifeguards”, “How to have a safe abortion”, “Everything you want to know about getting a pill abortion”, and “Abortion without barriers”. For a person who has little to no access to these educational resources, the internet can be very helpful to diminish barriers. Platforms such as Twitter or any social media site can make access to information about sexual education, reproductive health, and abortions unchallenging, too.

Organizing Through the Internet

Although this collective is known for their internet presence, it is important to note the history before they started using online platforms. Liz Meléndez states, “#NiUnaMenos es, sin duda, un hito en la historia del feminismo global y local, pero es también el resultado de luchas previas. Las marchas contra la violencia contra la mujer tienen más de 30 años […]#NiUnaMenos saca las luchas de los entornos feministas tradicionalmente organizados y lo extrapola, convocando a personas no involucradas en este círculo, gracias también a la comunicación globalizada/#NiUnaMenos is undoubtedly a milestone in the history of global and local feminism, but it is also the result of previous struggles. The marches against violence against women are over

30 years old […] #NiUnaMenos takes the struggles out of traditionally organized feminist environments and extrapolates it, summoning people not involved in this circle, thanks also to globalized communication” (2018). With that being said, Ni Una Menos utilizes the internet and social media to organize rallies for the legalization of abortion. At the height of the movement, “Social media served as the best platform for speaking out freely and for the people to come together and discuss the gender-based issues” (Where is Your Line? 2020). Outside of the internet, the collective has had marches with over thousands of women gathered in front of congress. Through social media, they were able to mobilize and spread word about the protests/marches. The marches even gained support from people outside of Argentina because they became widely publicized through the internet. During the marches, women held signs supporting legal abortion and banners pushing congress to meet their demands.

Ni Una Menos collective has shown how they have used the internet as a vessel to push for reproductive rights and fight for legal abortion.

Conciencia Feminista: Testimonies and Resources

The second collective I will be looking at is Conciencia Feminista. This collective hosts a website showcasing blogs from different women who talk about their abortions. The website’s origins are by Chilean feminists who live in a country that has strict regulations on abortion. The website not only includes the blogs’ section called “Yo Aborté/ I Aborted”, but also links to websites regarding reproductive health. This online platform helps create a safe space for women to unite for legal and safe abortion, better sexual education, and reproductive health. The collective states:

“Este es un blog del grupo feminista joven ConcienciaFeminista para difundir experiencias relativas al Aborto. Son escasos o nulos los espacios que tenemos en Chile para comentar, decir, informar y/o dialogar la experiencia de abortar en un país que tiene totalmente restringida esta posibilidad. Queda abierta la invitación para compartir nuestras experiencias de aborto, ya sean de dolor, alivio, esperanza, angustia, entre otras emociones y/o vivencias/ This is a blog from the young feminist group ConcienciaFeminista to disseminate experiences related to abortion. There are few or no spaces that we have in Chile to comment, say, inform and/or discuss the experience of abortion in a country that has this possibility totally restricted. The invitation is open to share our abortion experiences, whether of pain, relief, hope, anguish, among other emotions and/or experiences”

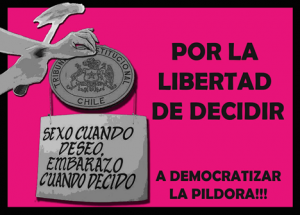

This is one of the many pictures posted on the website that explicitly shows what they fight for.

At the date the website has been accessed, there were over 20 entries of different women and their experience with getting an abortion, where it has been banned and criminalized. They expressed grief for the need to do it in secrecy under dangerous conditions. They fell into vulnerable situations when they seeked clandestine abortion methods. One author attended college, at the time of their pregnancy, and did not want to have a baby with their partner at the time. They decided to have an abortion and was injected with medicine veterinarians use. Another testimony was by a woman who lived in Chile. She states, after the abortion, “Pese al fuerte dolor que sentí en mi cuerpo durante la intervención (conocida en ese tiempo como ‘raspaje’), pese al temor que sentía por enfrentar esas condiciones casi insalubres, mi emoción más importante tras salir de allí fue un alivio inmenso/Despite the strong pain that I felt in my body during the intervention (known at that time as ‘scraping’), despite the fear that I felt about facing these unhealthy conditions, my most important emotion after leaving there was an immense relief.”

Another author expresses how isolated they had felt when they got the abortion; “Al fin…hoy puedo hablar de mi experiencia con este tema…recuerdo cuantas veces lloré sola y confundida, sintiéndome una basura pero a la vez aliviada; ese tipo de sensaciones extrañas, mezcla de rabia, culpa, angustia, y esperanza/At last … today I can talk about my experience with this topic … I remember how many times I cried alone and confused, feeling like garbage but at the same time relieved; those kinds of strange sensations, a mixture of anger, guilt, anguish, and hope.” At the end of the blog post, the author comes to the conclusion, “tenía la certeza de haber hecho lo correcto, pero me sentía desdichada, sola, y muy triste/I was certain that I had done the right thing, but I felt unhappy, lonely, and very sad.” The website also gives readers the option to create an account to share their testimony.

Along with blog entries from different authors, the website also has links to different resources pertaining to abortion and reproductive health. Topics include “En caso de tener diferencias de opinión con tu pareja respecto de un embarazo no deseado, lo más adecuado es/In case you have differences of opinion with your partner regarding an unwanted pregnancy, the most appropriate is”, “Aborto ¿cuando decido?/Abortion when do I decide?”, and “Cuáles son los método que has usado (o tus conocidas) para interrumpir un embarazo?/What are the methods that you have used (or your acquaintances) to interrupt a pregnancy?”. There are also links to other websites with information to obtain the abortion pill and how to have low-cost abortions.

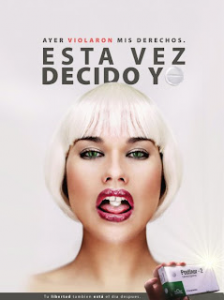

This is one of the pictures posted along with links to more information about the abortion pill. Translation: “Yesterday they violated my rights. This time I decided.”

Online Spaces for Women

It is important to note there is a lack of data for internet usage between genders in Latin America. If we go back to the first framework and the digital gender gap in technology, online spaces like the Ni Una Menos twitter profile and the Conciencia Feminista website encourage more participation from women on a male dominated internet. The twitter profile has options for people to interact and comment under the tweets uploaded by the Ni Una Menos collective. The videos they upload to show their support for legal abortion, specifically panders to women or people who are non cis men.

Similar to that, because of the nature of the website made by Conciencia Feminista, participation from women is necessary for the blog posts to continue. With that being said, readers can also create a profile and share their testimony, meaning there are no barriers for people who want to share. This is important because there is no exclusion of any identity, in contrast to a male dominated internet that breeds misogyny.

Going along the same vein, these collectives have brought awareness to the reasons why women need abortions and how life or death it can be because of clandestine abortions. In Ni Una Menos’ case, they used social media to organize marches to congress in Argentina. They took to the streets to express their disapproval of the reproductive laws in Latin America. The second framework explained the criminalization of abortion and the lack of reproductive rights in Latin America, which is an issue that negatively impacts people greatly, as I have explained previously. The collective’s decisions to upload videos of health care workers is impactful because they have people with influential positions, given their job occupations, explain why they support abortion, reproductive health, and expansion on sex education. People can watch the videos on a social media platform that is easily accessible.

Similarly, the Conciencia Feminista collective makes the testimonies on their website easily accessible, too. With abortion being a taboo topic, they recognize the importance for people to share their stories. People can feel less alone in a situation widely experienced in countries that ban and criminalize abortion. As mentioned earlier, anyone can have access to the testimonies and website. People have expressed their gratitude for the space to share their feelings and experiences. Since the collective has links to information on sexual health, reproductive health, and abortion pills, people can be informed. Going back to ECLAC’s (2020) definition of physical autonomy, both collectives advocate for it in the work they have done. The heart of these collectives is centered around women’s physical autonomy, and the decision whether to abort or not falls under that. These collectives understand the violence perpetuated by the government when abortions are outlawed. A value emphasized on both of the online platforms is women’s decision comes first. Women undergo dangerous under the table procedures and feel shame or anger from it. This work has been important for the advancement of women’s reproductive rights because these cyberspaces help bring women together who want safer and better conditions to have abortions. The healthcare workers, mentioned previously, emphasized how life or death clandestine abortions can be to women. They also mentioned abortions will keep happening regardless of the criminalization of it. Both collectives help unite women’s voices to combat the violence they experience from the ban on abortion by Latin America governments. Ni Una Menos takes it a step further and organizes offline to ensure there is change in the reproductive laws.

Furthermore, the values held by the two collectives are shared with the feminist movement. I will now apply my last framework to understand these collectives as not only advocates for reproductive rights but use cyberfeminism to their advantage in the fight for reproductive rights in Latin America. If we look back to the 15 Online Feminist Principles, both collectives fall under all the principles. For instance, Principle 2 states, “A Feminist internet is an extension, reflection and continuum of our movements and resistance in other spaces, public and private.” This principle is evident in the collectives’ work because they both use the cyber spaces to congregate and create change outside of online spaces. The blog posts about abortion are used to resist the punitive abortion laws in Chile, and the use of social media helped rally supporters to march to congress in demand of the same change in Argentina. These online spaces are extensions of the fight for reproductive rights in Latin America. Another example of these collectives falling under the cyberfeminists’ principles is Principle 8. It states, “As feminist activists, we are politically committed to creating and experimenting with technology utilizing open-source tools and platforms.” Using online spaces can be unconventional in the fight for reproductive rights, but both collectives use them to their advantage in resistance to their governments’ harsh restrictive abortion laws. For the case of ConcienciaFeminista, they utilized blog posts that can be created by anyone as a tool for women to openly talk about abortion which is banned in Chile. This is creative because no one is excluded from sharing or reading blog posts. It is an open source that is easily accessible. As for Ni Una Menos, the videos they uploaded were also open sources. Anybody with an email who can create a twitter account can access those videos. They can also access information on how they can support the movement by showing up and participating in the marches organized. Last example is Principle 13, “We strongly object to the efforts of state and non-state actors to control, regulate and restrict the sexual lives of consenting people and how this is expressed and practiced on the internet.” This principle is very evident in the creation of these collectives and their purposes. To reiterate again, the cyberspaces are created in opposition to Latin American governments that regulate women’s bodies by banning and criminalizing abortion. It is obvious these laws can be dangerous and violent towards women who have an unwanted pregnancy. The decision for a woman to have an abortion should fall on her, not the government.

Criticism of Cyberfeminism/Digital Activism

Although online spaces can be helpful for movements, to what extent do they help the movement move forward? Digital activism is still very recent as it has been used by social media/internet users, mainly in the last 15 years. Santan-Macias critiques digital activism, because media coverage’s portrayal of social media is not able to represent the complexity of the movement. There is criticism for the popularity the Ni Una Menos collective gained on Twitter, too. Santana-Macia argues that movements on social media can be “defined by their tools rather than causes themselves, meaning that social media tends to be glorified while the cause’s importance is dismissed”, through media coverage (March 2021). Only one side can be portrayed, and nuances of the movement can be completely missed. The center of attention can only fall on the collective’s use of social media, and the popularity it gained quickly. The history and organization done before the collective even used their social media platform can be disregarded. Because the collective is known transnationally for their social media platform, they are at danger for only being known for that. This may not even be the fault of the collective itself. There is media coverage headlines like “How Twitter Activism Made Violence Against Women a Campaign Issue in Argentina”, “How One Tweet About Femicide Sparked a Movement in Argentina”, but there has been a history of feminists in Argentina who fought against the violence against women before it gained attention on social media. This history can be overlooked by people learning about the movement. Since the movement has no control over media coverage of their social media, they are unable to completely illustrate to mass audiences what they stand for. The integrity of the movement can be jeopardized if people do not understand the history in Argentina of women fighting the same issues before they had the name #NiUnaMenos. Because of the mass interaction created by social media, sometimes there is a “loss of control over the message” that can lead to a “dilution of common frames and entities” which can be the case for the collective in Argentina (Dumitrica and Felt, 2018). If the message takes on a different meaning because that is how people are interpreting it, that can cause damage to the integrity of the movement. This is not sustainable for long term movements. People will believe the change the collective has made was only through social media, which is not true. The collective only uses the online platform as a hand in their movement/ struggle for reproductive rights.

With that being said, there is also criticism of the mode the collective has used to organize offline. To specify, Twitter and other social media apps were not created with activism in mind (Harlow, 2012). Apps such as Facebook and Twitter were created for users to use them as much as they can to generate profit (Dumitrica and Felt, 2018). This can lead to little to no effort seen in digital activism called “slacktivism”. On Dictionary.com, it is defined as “the practice of supporting a political or social cause by means such as social media or online petitions, characterized as involving very little effort or commitment”. This can look like sharing online petitions, changing someone’s profile image to support a certain movement, etc. Furthermore, it is a feel-good action done by the participant but has no actual political participation, political impact, or social impact (Skoric, 2012). Slacktivism can be detrimental for social movements because it can go against the nature of it. Goodwin and Jasper explained the nature of social movements, the “innovation in values and political beliefs often arises from the discussions and efforts of social movements”, and they “develop new ways of seeing society and new ways of directing” society (2015). One can argue little to no political participation is not innovative or a new way of seeing/directing society at all. Online political participation can be useless at times.

However, the purpose of the participation in cyberspaces can help constitute whether it is activism or slacktivism. The major difference between the two is “the reduction of resources typically needed for engaging in political activities online” (Skoric, 2012). Participating politically on a social media platform has reduced resources than participating politically offline. One is able to easily sign an online petition resulting in little to no resources given by the individual, whereas someone offline would have to contribute more of their resources, such as time, in order to contribute to whatever social movement they are a part of.

With that being said, that is not the case for the collective’s work online. It is obvious these collectives have put so much effort and time into their online platforms. Given the history of Ni Una Menos, their social movement against gender violence started offline years before they created their twitter account. The resources people have given to the movement can be seen through the marches to congress. The collective did post on their Twitter account, but the goal was to get people to physically show up to their rally. For ConcienciaFeminista, their efforts and resources are more than what a slacktivist would contribute. They understand the seriousness with the issue of abortion is in Chile. They include helpful and vital resources on their website for anyone who needs an abortion. The blog posts are not considered slacktivism, although typing and posting them can seem little to no effort, but that is not the case. The people sharing their testimonies also share their shame, guilt, and relief from having these abortions. Their blog posts are very personal accounts of the dangerous and violent conditions they face.

Conclusion

It is prevalent feminists are putting so much effort in the fight for reproductive rights in Latin America. One tool they have used is the internet and social media. They have used these modes of resistance against strict abortion laws in Latin America. This helps bring pressure to lawmakers to understand the ramifications of criminalizing abortion, and the negative impact on women who carry out unsafe clandestine abortions. This tool has been recently created and used, so it is important to critically analyze its contribution to the social movement. Although there is concern these online spaces and platforms can hinder the movement, I believe cyberfeminism has helped move it forward. Cyberfeminism can be used, but it is important to make sure there are efforts going on outside of cyberspaces. We can see in the collective’s work there is a contribution of individual efforts to advocate for reproductive rights in countries with punitive laws on abortion. Their presence online is very important as well because they are able to combat a male-dominated internet and appropriate the resources for the advancement of the feminist movement. They can break binaries and create online spaces to unite women who share the same struggle. Just like the cyborg that is a machine and an organism. It’s able to transition back and forth and the same can be said for feminists who use internet spaces to further the movement, but also using offline spaces too.