16 Zapatista Women and Their Inherently Intersectional Identities -Ana Roig

aroig4907

Introduction

Throughout the course of the 20th century, women, particularly women of color, have played crucial roles in grass-root social movements that have aided in the liberation of women and fought against racist and classist structures of power. One well known social movement is the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) from the Chiapas region in Mexico. Women were particularly influential in this movement as they held political and military roles through all ranks of the EZLN. Women in the region were previously marginalized under the structures of the patriarchy, but through the formation of the EZLN, women were able to create new realities for themselves. This paper aims to explore and understand the lives and roles of Zapatista women in the EZLN under the theoretical frameworks of intersectionality and identity. It is imperative that any examination of the Zapatista women consider their intersecting identities, as excluding this consideration does not recognize that the lived experiences of these women are inherently influenced by their intertwined identities. Their positions as women and indigenous cannot be separated.

To begin, I will provide a brief overview of the history of the EZLN and introduce the Women’s Revolutionary Law. Then, I will detail the testimony given by several Zapatista women in Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories. The section on testimony is split into three different sections that relate to women’s roles in the EZLN: Zapatista women’s experiences prior to the formation of the EZLN, Zapatista women as insurgents and military involvement and Zapatista women and the creation of the Women’s Revolutionary Law. This leads to the review of the theoretical framework on intersectionality and identity that will be applied to the testimony of the Zapatista women in my analysis.

The findings of my analysis on the participation of indigenous women in the EZLN indicate that Zapatista women play a crucial role in the resistance efforts of the EZLN and thus play a crucial role in furthering the liberation of women. My analysis also concludes that Zapatista women’s effective participation in EZLN resistance efforts is entirely due to their perspectives and experiences as individuals who possess intersectional identities. Furthermore, while working with the EZLN, women were able to focus on resistance efforts that addressed their identities as indigenous but also as women.

A Brief Overview of EZLN History

On January 1, 1994, the same day that the North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was being implemented, the EZLN came out of hiding and occupied the towns of Altamirano, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Ocosingo, and Las Margaritas (Schmal, 2019). They declared war on the Mexican government and made demands for work, land, housing, food, health, education, independence, liberty, democracy, justice, and peace (Godelmann, 2014). Originally formed in 1983, the EZLN spent ten years as a clandestine organization before their declaration of war. They spent those years secretly organizing the indigenous people of the Chiapas region into a guerilla army and grassroots social movement. The formation of the EZLN and their eventual declaration of war on the Mexican government can be traced back to the historical marginalization of the Chiapas indigenous people. Furthermore, it can also be attributed to the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (Godelmann, 2014).

Throughout Mexican history, the Chiapan indigenous people’s that make up the EZLN have faced intense marginalization, inequality, and exploitation. The institutions of power subjected these people through economic, political, and social means. Although Chiapas is one of the most resource-rich regions in Mexico, due to the legacy of colonialist practices that resulted in the concentration of land and wealth for the elite, indigenous people in the region were not able to reap the benefits (Klein, 2015). Moreover, they were also excluded from the governmental decision-making process at every level: local, state, and national. This meant that the indigenous people of Chiapas had no influence on the political decisions being made that would directly impact them. Lastly, because of the longstanding social institution of racism, indigenous people lacked basic human rights and services such as healthcare and education (Klein, 2015). When NAFTA was due to be implemented, the EZLN saw it as an attack on indigenous people. After having suffered extreme historical inequality, the implementation of NAFTA added another reason for the EZLN to declare war on the Mexican government. The EZLN believed that the implementation of NAFTA could create opportunities for capitalist backed US and Canadian business to purchase indigenous land and remove the people who previously used that land (Godelmann, 2014).

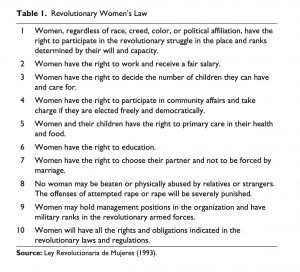

Prior to the 1994 uprising, the EZLN passed the Women’s Revolutionary Law in 1993, which gave women basic rights not granted to them before. The law was created with the input of indigenous women throughout the Chiapas region. Given that women in the region had previously been excluded from decision-making processes and marginalized under the structures of the patriarchy, it truly was revolutionary for the EZLN to pass the law (Law, 2019). Further information will be provided on the law in the testimonies detailed in the case study. Below is a table provided by Clara Bellamy (2021) showing the law.

Literature Review

On Intersectionality

Audre Lorde’s piece The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, is her response to her experience at the New York University Institute for Humanities conference a year prior. The focus of the panel was on feminism; however, Lorde was one of only two black women invited to speak at only one panel. In response to this, Lorde introduces the idea of interdependency. Interdependency is defined as the advocation of difference in a way that views said difference as a necessary polarity in the lives of women which can ultimately lead to a unified vision for the future. Women have been taught to see their differences as cause for separation or to completely ignore them rather than seeing their differences as a tool for change. The only way towards liberation is through the creation of community obsolete of these conceptions of difference. Lorde asserts that women must learn how to turn their differences into strength, “for the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde, 1984).

In her article, Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color, Kimberle Crenshaw explores the race and gender dimensions of violence against women of color. She asserts that contemporary feminist and antiracist discourses have failed to consider the intersectional identities of women of color. She focuses on battery and rape in considering how women of color’s experiences are shaped by the intersection of racism and sexism but are often left out of mainstream discourses on antiracism and feminism. She argues that women of color’s intersectional identities are “both women and of color within discourses that are shaped to respond to one or the other, women of color are marginalized within both” (Crenshaw, 1991: 1244). Crenshaw divides her argument into three categories: Structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality. In part I, she argues that the intersection of race and gender that women of color exist in makes the experience of gender-based violence qualitatively different than that of white women. In part II, Crenshaw argues that both feminist and antiracist politics have aided in the marginalization of the issue of violence against women of color. And, finally, in part III she argues that the representation of women of color in popular culture is another source of the intersectional disempowerment of women of color (Crenshaw, 1991). This journal uses violence against women of color as a framework to analyze the dimensions of intersectional identity. Crenshaw’s article provides an understanding of intersectionality that utilizes the interactions of race and gender within the context of violence against women of color.

Similarly, Elina Vuola presents and analyzes the concept of intersectionality and applies it to Latin America gender studies in Intersectionality in Latin America? The possibilities of intersectional analysis in Latin American studies and study of religion. She proposes that intersectionality is a useful umbrella term for theoretical purposes, but to fully conceptualize intersectionality one must shift their lens to the question of difference (Vuola, 2012: 135). Vuola argues that intersectionality is not a unified approach, but rather a way to combine the central developments in recent feminist theory under the umbrella of one concept. The development and application of intersectionality is primarily in response to the analyses of gender that ignore the differences between the experiences of women as it pertains to racial identity. With this, Vuola argues that, in Latin America, the “inclusion of issues of race, class, and ethnicity in gender was well developed before the term intersectionality was even coined” (Vuola, 2012: 135). Because of this, Vuola proposes that while an umbrella term like intersectionality is useful for theoretical purposes, it gains traction through application to specific contexts and concrete examples.

On Identity

In the first chapter of The Power of Identity, titled “Communal Heavens: Identity and Meaning in the Network Society,” author Manuel Castells explores the idea of identity in relation to social movements. As it refers to social actors, Castells defines identity as “the process of construction of meaning on the basis of a cultural attribute, or a related set of cultural attributes, that is given priority over other sources of meaning” (Castells, 2010: 6). He argues that identities can also originate from powerful institutions and that they become identities when social actors internalize them. Because identities are constructed under the context of existing power relationships, Castells presents three forms of identity building. These forms are legitimizing identity, resistance identity and project identity. Each form of identity building leads to different outcomes in said society. Legitimizing identity is defined as “introduced by the dominant institutions of society to extend and rationalize their domination vis a vis social actors” (Castells, 2010: 8). This form of identity is the basis for the creation of civil society. Resistance identity is defined as “generated by those actors who are in positions/conditions devalued and/or stigmatized by the logic of domination, thus building trenches of resistance and survival on the basis of principles different from, or opposed to, those permeating the institutions of society” (Castells, 2010: 8). Resistance identity leads to the creation of communities and communes. Lastly, project identity is defined as “when social actors, on the basis of whatever cultural materials are available to them, build a new identity that redefines their position in society and, by so doing, seek the transformation of overall social structure” (Castells, 2010: 8). The construction of project identity produces what are referred to as subjects. Subjects are the collective social actor through which individual people can find meaning in their experiences. These three forms can be utilized in examining different social movements and their actors.

Zapatista Women as Political Subjects and as Feminists

The article “Insurgency, Land Rights and Feminism: Zapatista Women Building Themselves as Political Subjects,” written by Clara Bellamy, discusses how Zapatista women were able to transform themselves into political subjects that fought against the racist, patriarchal, and capitalist powers. Bellamy concludes that previously ignored and silenced Zapatista women, through political participation, were able to gain recognition and command (Bellamy, 2021: 103). Being involved in the ranks of the EZLN gave women the opportunity to have spaces for discussion and consciousness building. They were able to transform their previous lived experience under the structures of patriarchal control to participate politically.

Bellamy notes that when examining Zapatista women, it is important to not debate on whether these women are feminists. Doing so would place an academic, homogenizing model of what feminism is on the Zapatista women. Judging them based on white academic standards for feminism would be to further fall into colonialist practices (Bellamy, 2021: 102). Zapatista women do not assume themselves as feminists, and even though they may fit our conceptions of feminism, it is crucial to not impose our voices and ideas on them.

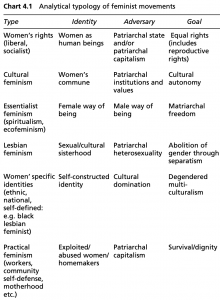

Although Zapatista women may not call themselves feminists, they still can be. The claim presented above by Bellamy is true if only one definition of feminism is accepted. In the fourth chapter of his book, “The End of Patriarchalism,” Castells proposes a typology of feminist movements. He writes that feminist movement’s strength and vitality come from its diversity and adaptability. Castells does note that his typology “cannot render the multifaceted profile of feminism across countries and cultures” (Castells, 2010: 253), however, it can be useful in starting to understand the diversity of feminist movements. Below is a table provided by Castells displaying the different types of feminist movements.

The Case: Women in the EZLN

Since the formation of the EZLN in 1983, women have been involved every step of the way. In the decades that followed, indigenous women from the Chiapas region experienced changes in their lives, communities, and political participation. Although the EZLN is not inherently a women’s movement, it did create new opportunities for Zapatista women and gave them leadership roles within the movement. Zapatista women served as insurgents, political leaders, educators, and key agents in autonomous economic development (Klein, 2015). The experiences indigenous women had within the Zapatista movement are detailed in the testimony collected and organized by Hilary Klein in Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories. This testimony provides the stories of Zapatista women who were involved in all aspects of the EZLN.

Zapatista Women’s Experience Prior to the Formation of the EZLN

The testimony of Maria, a Zapatista woman from the autonomous municipality Miguel Hidalgo, illustrates the experiences of women prior to the formation of the EZLN and passage of the Women’s Revolutionary Law. In reflecting on her childhood in an interview with Klein, Maria recounts her suffering at the hands of her father. Her father would often beat her mother and throw her out of the house. Maria also had the dream of going to school, but her father refused because she was a girl. Instead, Maria started working at a very young age to help her family. Because she was the oldest of the sixteen children her mother had, Maria was always helping her mother in the kitchen. She also had to help because her mother was sick very often and they did not have the knowledge of hospitals or access to medicine. Eventually, when she was seventeen, she was forced into an arranged marriage by her parents. Once married, her husband would spend all their money on alcohol, forcing Maria to work raising livestock to provide for her family. Both Maria and her husband joined the EZLN in 1994 after men and women insurgents would come speak to them. She began her involvement in the EZLN as a local representative. Prior to joining the EZLN her husband would not give her permission to leave the house, but after joining in 1994, Maria reflects that he started to change (Klein, 2015).

As detailed in the testimony provided by Maria, women living in the Chiapas faced a harsh reality as their lives were controlled by their fathers and husbands. However, the formation of the EZLN and women’s involvement made way for a new reality for Zapatista women.

Zapatista Women as Insurgents and Military Involvement

In the EZLN, women fought alongside men as insurgents. As explained by Major Ana Maria, the women would do political work in villages along with learning combat tactics. Within the army of the EZLN, men and women are viewed equally. They all receive the same training and can achieve the same military ranks. Ana Maria had the rank of insurgent major, meaning she had command over a battalion of soldiers and would direct them when in combat (Klein, 2015).

The testimony provided by a woman named Isabel, one of the first women to join the EZLN, also provides insight on women’s roles as insurgents. Isabel joined the EZLN in 1984 at fourteen years old, and ten years later during the uprising, she was a captain leading a battalion. She reflects that she was very young when she started thinking about her surroundings and experiences. She had to grow up very quickly because of the poverty her family lived in. She was the oldest daughter and thus a lot of domestic responsibility fell on her shoulders. During this time, Isabel was also going to school and had the desire to continue educating herself. When she was invited to join the EZLN, it was very hard to leave her community, but she wanted to commit herself to a movement after seeing the suffering of women around her. At first, she lived in the city for a year, taking the time to educate herself on the injustices her community faced and the reasoning for these injustices. She also studied politics and ways of organizing. After a year Isabel decided to go live in the mountains as an insurgent. There she learned about using weapons and the responsibility that comes with it. After being taught political-military lessons, Isabel decided that she wanted to participate in the EZLN as a combatant. Before stepping down in 2003, Isabel spent two decades of her life as a combatant and military leader (Klein, 2015).

Zapatista Women and the Creation of the Women’s Revolutionary Law

Further testimony provided by Isabel shows how the political education and organization of women prior to the 1994 uprising resulted in the Women’s Revolutionary Law. Isabel was one of the women who participated in the process of the creation of the law. As told by Isabel, Zapatista women began to organize talks with women and their entire communities throughout the Chiapas region. They would speak to the women about the reasoning for the existence of the EZLN, but they would also tell the women about their rights and how to participate politically. There was pushback from men, but through the process of political and educational work, women’s consciousness was raised, and they began to actively participate more (Klein, 2015). Isabel further details that these meetings gave women the space to express their emotions and discuss how they wanted to change their lives. The ideas presented by the women in these meetings provided the framework for what would become the Women’s Revolutionary Law. The women insurgents who attended these meetings were not the ones to write the law. They attended to translate and gather demands from the women. It was then that each Zapatista region created their own draft of the law, which were all compiled and sent back to be reviewed. The Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee (CCRI), the EZLN’s body of political leadership, passed the law in 1993 and in 1994 it was made public (Klein, 2015). In reflecting on the Women’s Revolutionary Law, Isabel says “We made a commitment to fight against injustice, and we knew that men and women united, with the same rights, with the same opportunities within our organization, could unite our forces against the capitalist system” (Klein, 2015: 187).

The story of Comandanta Ramona also provides insight on how the Women’s Revolutionary Law came to be. When Ramona was younger, she left her town in search of work. It was then that she noticed the disparities between bigger towns and rural communities (Morales, 2011). For two decades, Comandanta Ramona played an integral role as a military and political leader in the EZLN and was highly respected as a member of the CCRI (Klein, 2015). Ramona, alongside Major Ana Maria and Comandanta Susana, collected anonymous suggestions from the indigenous women that would form the foundations of the Women’s Revolutionary Law (COHA, 2011). Comandanta Susana was also responsible for going to speak with women from different communities, and for synthesizing all the input into what would become the Women’s Revolutionary Law. When the CCRI met to vote on different laws in 1993, Susana was the one who presented the “proposals that she had gathered from the ideas of thousands of indigenous women” (Klein, 2015: 180).

The passage of the Women’s Revolutionary Law paved the way for active participation of women in their communities and allowed them to escape extreme marginalization under the structures of the patriarchy. Although this is the case, it was not always easy to implement the law due to sexist pushback, however, “within the framework of revolutionary transformations and for the sake of collective social transformation, the Zapatistas have had to assume gradually and in a disciplined manner what was agreed in the recognized organizational and decision-making spaces” (Bellamy, 2021: 92). In an interview with a journalist, Zapatista Captain Maribel explained how the law transformed women’s lives. She noted how the men started to see women become more politically prepared and able to defend themselves (Klein, 2015). She further recalls that “It was strange for some men, because they could no longer beat their wives so easily, and they couldn’t force us to marry someone our father wanted us to marry. If the woman doesn’t want him, she doesn’t want him. Now women can also denounce their husbands. She can tell the authorities, ‘Look, this is what’s happening and I don’t want it to be happening to me.’ Or, ‘He’s been beating me.’ They can speak up and denounce it” (Klein, 2015: 185-186).

Analysis

“This dual and interdependent relationship between women’s liberation and social revolution illustrates that popular struggles cannot achieve collective liberation for all people without addressing patriarchy and, likewise, women’s freedom cannot be disentangled from racial, economic, and social justice” (Klein, 2015)

When examining the lives of Zapatista women, it is crucial that their intertwined identities as indigenous, impoverished women are not ignored or separated. As put by Comandanta Ester in a 2001 speech in Mexico City, “We are oppressed three times over, because we are poor, because we are indigenous, and because we are women” (Klein, 2015: 24-25). Although Zapatista women were part of an organization dedicated towards agrarian reform, their heavy involvement at all levels of the EZLN also led the way for women’s liberation in the region. Through their active participation in the EZLN, Zapatista women were able to create the space for “discussion, transgression, and political transformation” (Bellamy, 2021:19). This created a new organizational framework for the women to broaden the struggle for their demands, and eventually organize to create the Women’s Revolutionary Law (Bellamy, 2021).

The participation of women in the EZLN can be analyzed through the framework provided by Lorde (1984). Lorde’s framework emphasizes the idea that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde, 1984). In the case of Zapatista women, the master’s tools can be defined as any action or resistance effort that subscribes to the ideas perpetuated by the institutions of the Mexican state; primarily the patriarchal structures that place men as the heads of household and the heads of society. Within the EZLN, women have equal opportunity to participate in both political and militia efforts, which is often not common in other resistance movements. This directly defies the role that the patriarchy assigns to women, particularly impoverished women of color, as subordinate and submissive. Through the testimony of Isabel and Ana Maria, it can be seen that indigenous women play an essential role in the resistance efforts of the EZLN as both of them were able to participate in EZLN efforts as high-ranking insurgents. Lorde argues that “only within a patriarchal structure is maternity the only social power open to women” (Lorde, 1984: 111). Following this argument, the power of women within the EZLN is not maternal or nurturing, their participation transcends this conceptualization of womanhood. Within this framework, Lorde argues that once resistance surpasses the utilization of the “master’s tools”, real and lasting change can be achieved. In the case of Zapatista women, this can be seen through the formation of the Women’s Revolutionary Law. Women’s active participation within the EZLN and their organizing efforts directly led to the creation and passage of the Women’s Revolutionary Law. As shown in Isabel’s testimony, Zapatista women organized meetings for indigenous women in different communities to teach them how to politically participate but also gain their input on how to better their lives. Comandanta Ramona and Susana also collected input, with Comandanta Susana being responsible for synthesizing all the input and presenting the proposal for the Women’s Revolutionary Law to the CCRI. Furthermore, after the passage of the law, as described by Captain Maribel, women finally had the power to stand up for themselves against the traditional systems of the patriarchy. This demonstrates that the power of women of color outside of the patriarchal structures of society can lead to the defining of entirely new roles for women within political organization efforts. Their dismissal of the master’s tools and the redefining of the roles of women in resistance efforts allowed for the formation of genuine change in the structure of their society.

Furthermore, Zapatista women’s role within the EZLN can also be understood through the framework outlined by Crenshaw (1991). For the purposes of this analysis, the most relevant aspect of this framework is the concept of political intersectionality. Crenshaw outlines a pitfall of political intersectionality that can aid in the understanding of the role of indigenous women in the EZLN. Crenshaw argues that because women of color are members of two or more marginalized communities, their political energies must often be split between two opposing groups (Crenshaw, 1991). This concept leads to intersectional disempowerment, which can be defined as a phenomenon where the possession of two subordinated identities leads to alienation from the political resistance efforts of both identities. The application of this framework to the women in the EZLN is with the purpose of emphasizing how the structure of the EZLN contrasts with Crenshaw’s definition of political intersectional disempowerment. Zapatista women in the EZLN possess several intersectional identities; They are impoverished, indigenous, women of color. In typical resistance efforts, the goal of the resistance would fight for the rights of one subset of these identities. Yet, the EZLN plays a role in furthering the resistance efforts of multiple communities. The EZLN was formed for the purpose of agrarian reform, which addresses the needs of both impoverished and indigenous communities (Godelmann, 2014). Additionally, as seen through Lorde’s framework, the EZLN also transcends the patriarchal structures of society to further the women’s rights movement within their community. Because of this, women of color in the EZLN who possess multiple intersectional identities are not forced to split their political energies. In fact, their resistance through the EZLN encompasses all of their identities and allows for them to participate in a way that does not result in intersectional disempowerment. Comandanta Ramona encapsulates this idea perfectly. After helping organize the 1994 uprising, Ramona was involved in a political campaign to end the discrimination of indigenous people in Mexico (COHA, 2011). In this regard, Comandanta Ramona was participating due to her identity as an indigenous person. However, she also heavily focused on defending women’s rights. Ramona would travel to different communities to teach women about the Zapatista struggle, which helped raise their consciousness (Morales, 2011). Moreover, she was responsible for helping organize and create the Women’s Revolutionary Law. Comandanta Ramona’s story shows how women in the EZLN were not forced to split their political energies. They were able to fight against the institutions of power that discriminated against them for being indigenous, while also fighting for the advancement of indigenous women’s rights in the region.

The framework provided by Vuola (2012) can also be used in examining the participation of women in the EZLN. Vuola argues that Latin American resistance efforts have been inherently intersectional before the term was even coined. With that, she argues that intersectionality was created to critique the analyses of gender that obscure difference (Vuola, 2012). This framework is important in understanding the role of women in resistance efforts of the EZLN. The EZLN does not necessarily highlight difference in the classical sense that we see argued in many other academic works, but it also does not work to obscure difference within their resistance. It is important to any analysis to understand the cultural context of resistance efforts that do not always follow a classically academic format. The EZLN, and women within the EZLN, operate from an inherently intersectional perspective. Their community as a whole possess an intersection of various identities, and their resistance work reflects that. As stated above, the EZLN does not force women of color to split their political energies to fight for the rights of a sole community. In this way, the EZLN allows for the presence of difference in their resistance efforts in a manner that encourages resistance to multiple power structures and does not prioritize the needs of one group over another. Once again, this is demonstrated by Comandanta Ramona, but also by Comandanta Susana and Isabel. All three witnessed the injustices indigenous people suffered in Chiapas, leading them to participate as military and political leaders in the EZLN. Their participation within the EZLN aided in the organization’s efforts towards land reform and defending indigenous interests. However, the women also noticed how their identities as women further marginalized them within their society. While helping the EZLN, the three women were able to organize meetings to educate women and aided in the process of the creation of the Women’s Revolutionary Law. Within the EZLN, Comandanta Ramona, Susana and Isabel were able to engage in resistance work that addressed their intersecting identities as women, indigenous, and lower class.

This conversation of intersectionality and resistance in relation to the women of the EZLN relates back to Bellamy’s (2021) argument that Zapatista women should not be defined as feminists. Due to their intersecting identities, women of the EZLN have been involved in resistance to racial, economic, and social injustices. Their work within the EZLN does not solely focus on the advancement of women’s rights, and thus they should not be labeled as feminists under the traditional, white academic definition of feminism. However, as stated previously, although Zapatista women may not define themselves as feminists, they still can be in different ways. Working under Castells (2010) typology of feminist movements, Zapatista women’s resistance efforts could be seen as the defense of women’s rights, cultural feminism, or practical feminism. In practical feminism, women may be close to feminism in practice “while not acknowledging the label or even having a clear consciousness of opposing patriarchalism” (Castells, 2010: 259). Although the work by Zapatista women may be feminist, they chose to ignore that label and focus on their intersectional identities as the reason for their participation in the EZLN. However, efforts by Zapatista women to organize and create the Women’s Revolution Law can be defined as the defense of women’s rights. Castells views this type of feminism movement as an extension of the human rights movement, working under the fact that women are human beings, not possessions (Castells, 2010). The work of women like Comandanta Ramona sought to fight the patriarchal structures and give indigenous women new rights in the region. With the passage of the Women’s Revolutionary law, indigenous women were no longer considered under the rule of men in their lives. These same efforts in organizing and creating the Women’s Revolutionary Law can also be seen as cultural feminism which Castells defines as “based on the attempt to build alternative women’s institutions, spaces of freedom, in the midst of patriarchal society, whose institutions and values are seen as the adversary” (Castells, 2010: 255). By organizing meetings to educate indigenous women, Zapatista women were able to create spaces of freedom. In these spaces, women had their consciousness raised to the injustices that impacted their lives and had the ability to openly discuss how they wanted to see change in their lives. There is no one way to define Zapatista women. Their work was inherently intersectional and that must be acknowledged in any definition. Even operating under the typology presented by Castells, Zapatista women conducted themselves in a way that combined aspects from different feminism movements.

Lastly, Zapatista women’s participation in the EZLN led to a construction of a new identity for these women, which can be defined as project identity under Castells (2010) framework. As previously stated, project identity is defined as “when social actors, on the basis of whatever cultural materials are available to them, build a new identity that redefines their position in society and, by so doing, seek the transformation of overall social structure” (Castells, 2010: 8). As shown in the testimony of Maria, women faced a harsh reality in Chiapas prior to the formation of the EZLN. They were burdened with doing the brunt of the domestic work and being under the control of the men in their lives. As a child, Maria was not allowed to go to school because she was a girl and she had to help her mom with domestic labor because she was the oldest sibling. Maria was also forced into an arranged marriage where she then had to raise livestock to provide for her family. However, as seen in the testimony given by Isabel, women were able to effectively create new identities that gave them a new position within Chiapas society. Zapatista women organized meetings for indigenous women in different communities to teach them about the EZLN struggle and how to advance their political and social participation. The women were also given the space to discuss ways in which their lives could be made better. Through this process of political and educational work in the organized meetings, women’s consciousness was raised regarding the injustices they faced due to their intersecting identities, and thus they participated more than before. Their newfound, active participation culminated in the creation of the Women’s Revolutionary Law, which sought to change the societal structure that existed in Chiapas. Comandanta Ramona and Susana were responsible for collecting input from indigenous women throughout Chiapas, and then used the input to create the law. Susana was also the woman who presented the proposal for the Women’s Revolutionary Law to the CCRI. The law did positively impact indigenous women’s realities. For example, prior to joining the EZLN, Maria’s husband would not let her leave the house without permission, but after joining his attitudes and behavior toward women shifted, and Maria served as local representative. Furthermore, as described by Captain Maribel, once the law was passed, women were able to defend themselves with the new ability to speak up and denounce the actions of men in their lives. If they wanted to participate in their communities, their husbands could no longer make them stay home. If they were being abused, they could speak up about their husband’s behavior. Overall, Zapatista women were able to transcend the patriarchal structures of their society and thus were able to create new roles for women as political and social actors.

Conclusion

The stories of Zapatista women are powerful and highlight their resiliency. This paper aimed to explore their lives and roles in the EZLN in a way that focused on their identities through a lens of intersectionality. Beginning with an overview of Chiapas and EZLN history, this paper then detailed the testimony given by Major Ana Maria, Isabel, and Maria in Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories. Their testimony provided insight on the realities of women prior to the EZLN, but also showed how women were involved equally in the military and political organizing.

The frameworks presented by Lorde, Crenshaw, and Vuola on intersectionality help to further understand how the intersectional identities of Zapatista women allow the EZLN to dismantle patriarchal power structures within their own community and therefore become a much more effective force of resistance. The framework and typology presented by Castells, as well as the information presented by Bellamy, help to define the work Zapatista women and demonstrate the impact of their identities.

Through the findings in my analysis, the claim can be made that the structure and dynamics of the EZLN are inherently intersectional. This allows for Zapatista women to utilize their difference to further change within their society, which would not be possible if Zapatista women were forced to split their political agendas to align with a single marginalized community. The EZLN’s embracement of difference within intersecting communities is the root of their success as a social movement. It is of the utmost importance that other social movements follow in the footsteps of the EZLN in a manner that acknowledges intersectionality and identity to make lasting change in their communities.

References

Bellamy, C. (2021). Insurgency, Land Rights and Feminism: Zapatista Women Building Themselves as Political Subjects. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, 10(1), 86–109.

Castells, M. (2010 [1997]). Preface: xv-xviii; Introduction and Chapter 1: “Communal Heavens: Identity and Meaning in the Network Society,” pp. 1-45; 54-70 in The Information Age. Economy, Society, and Culture. Volume 2: The Power of Identity. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing (2nd edition)

COHA. (2011, July 18). Women’s Rights in Chiapas: Future Made Possible by the Revolutionary Law. Council on Hemispheric Affairs. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://www.coha.org/womens-rights-in-chiapas-future-made-possible-by-the-revolutionary-law/.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color” Stanford Law Review 43(6): 1241-1299

Godelmann, I. (2014, July 30). The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico. Australian Institute of International Affairs. Retrieved December 11, 2021, from https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/news-item/the-zapatista-movement-the-fight-for-indigenous-rights-in-mexico/.

Klein, H. (2015). Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories (Seven Stories Press first). Seven Stories Press.

Law, V. (2019, March 12). The Untold Story of Women in the Zapatistas. Bitch Media. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.bitchmedia.org/post/the-untold-story-of-womens-involvement-with-the-zapatistas-a-qa-with-hilary-klein.

Lorde, A. (2007 [1984]). “The Master’s Tools will never Dismantle the Masters House” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde. Berkeley: Crossing Press

Morales, N. (2011, May 23). Adventures in Feministory: Comandante Ramona. Bitch Media. Retrieved December 11, 2021, from https://www.bitchmedia.org/post/adventures-in-feministory-comandante-ramona-zapatista.

Schmal, J. P. (2019, October 20). Chiapas: Forever Indigenous. Indigenous Mexico. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://indigenousmexico.org/chiapas/chiapas-forever-indigenous/.

Vuola, E. (2012). “Intersectionality in Latin America? The possibilities of intersectional analysis in Latin American studies and study of religion” Serie HAINA VIII 2012: Bodies and Borders in Latin America.