15 Women as Elected Officials and Justices in Latin America and the Barriers They Face to Inclusion- Natasha Brown

Natasha Brown

Why Women in Decision Making Positions Are Important

Women have often been excluded from political decision-making spaces. Although the region of Latin America is a world leader in regards to women’s political participation, the goal of gender parity and equal representation has not yet been reached. Parity democracy, as defined by UN Women in Towards Parity and Inclusive Participation in Latin America and the Caribbean, is a democratic model in which equality between men and women is paramount to the inclusive and equitable transformations made by the State, with the objective of eradicating all forms of structural exclusion–particularly against women and girls–and in which both men and women assume shared responsibilities in all spheres of public and private life.[1]

The goal of gender parity can be examined through two lenses. Amartya Sen, in Development as Freedom, presents the ideas of the instrumental effectiveness of human freedom and the intrinsic importance of such freedoms.[2] Instrumental effectiveness examines the economic, developmental, and societal benefits of gender equality. There are greater practical advantages when women have freedom. When women have equal access to positions of power, they advocate for women’s-oriented policies.[3] This phenomenon has been demonstrated in countries like Brazil, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala. Women leaders also incorporate a gender perspective into their policies that ultimately lead to more inclusive environments that effectively include women,[4] as their agency can play a role in removing the inequities that diminish the well-being of women.[5] Additionally, women implement policies that not only benefit other women but the economy and society as a whole, thus for the sake of development, women must be included in decision-making spaces. The intrinsic importance of human freedoms proposes that women have the intrinsic right to freedom, regardless of if they individually do not care for personal autonomy.[6] Women must not be deprived of political representation or other means of decision-making. As a whole, equality for the sake of equality is enough. Regardless, it is paramount that gender parity exists outside the expectation that women put in the work to enact better policies for women, the poor, or society as a whole. Gender parity should not operate under the belief that women deserve freedoms solely due to the benefits that may incur from their inclusion.

Because of their exclusion from public politics, many women have adapted to occupy private political spaces, being highly active on the ground through social movements and working within organizations. In “Maneuvering the ‘U-Turn,’” Sonia Alvarez illustrates one way feminist activists have had a widespread impact: they work in collaboration with multiple groups, including women in political parties and female legislators.[7] The feminist approach must be multifaceted and work from various angles in order to counteract a multitude of obstacles. Thus, there is a need for women to be publicly represented in politics.

What Barriers Do Women Face Politically

However, barriers exist at each level that serve to hinder women’s participation in politics, and thus hinder the implementation of progressive policies promoting gender equity. It is essential to acknowledge the sociocultural and economic barriers that women face which limit their political participation in all forms, including their access to power in public decision-making positions.[8] These barriers include the delegation of unacknowledged work including care work and community work, the lack of legal protections under the law, the lack of educational and professional opportunities, and the expectation that women fulfill subordinate roles–not leadership positions. Even after overcoming the initial barriers to election, women legislators face pushback within their own political parties. In “LGBT Rights Yes, Abortion No,” Tabbush calls attention to the fact that feminist causes are often devalued within political parties, and that these parties may also marginalize and harass their own female legislators.[9] This leads to women being weary of promoting feminist policies so as to avoid paying internal costs. UN Women double down on this idea: political parties resist the transformation of rules, structures, and practices that excuse women.[10]

How to Overcome These Barriers

In order to combat the exclusions that women face at every level of politics, there are various approaches that have been posited. A common trend seen within various nations has been the implementation of mandatory gender quotas in order to equalize the political playing ground and offer women more opportunities.[11] Mandatory gender quotas require that a certain number or percentage of candidates are women, thus ensuring that women are at least an electoral option. Quotas are a form of affirmative action that acknowledges inequality and the need for temporary measures to accelerate progress in women’s political participation.[12] Affirmative action programs are essential for giving women fair conditions to politically and publically participate and seem to be the most popular approach. However, this is not the only approach that can be taken, as explored later in this discussion.

Women’s Political Participated in the Past vs Now

Women’s public political participation in Latin America has been limited across the decades. In 1948, Cuba was the first country to appoint a woman as minister or secretary of state.[13] In 1999, El Salvador and Nicaragua had zero women-appointed ministries or secretaries of state.[14] In Costa Rica, only 2 out of 14 political officials were women, thus the percentage of women in government stood at 14.2%, Argentina rested at 11.1%, Cuba’s percentage was a mere 7.1%, and in Brazil, only 1 in 24 officials were women (4.1%).[15] Out of the Latin American countries that had female governmental participation in 1999, Ecuador had the highest percentage of women in government at 28.5%.[16]

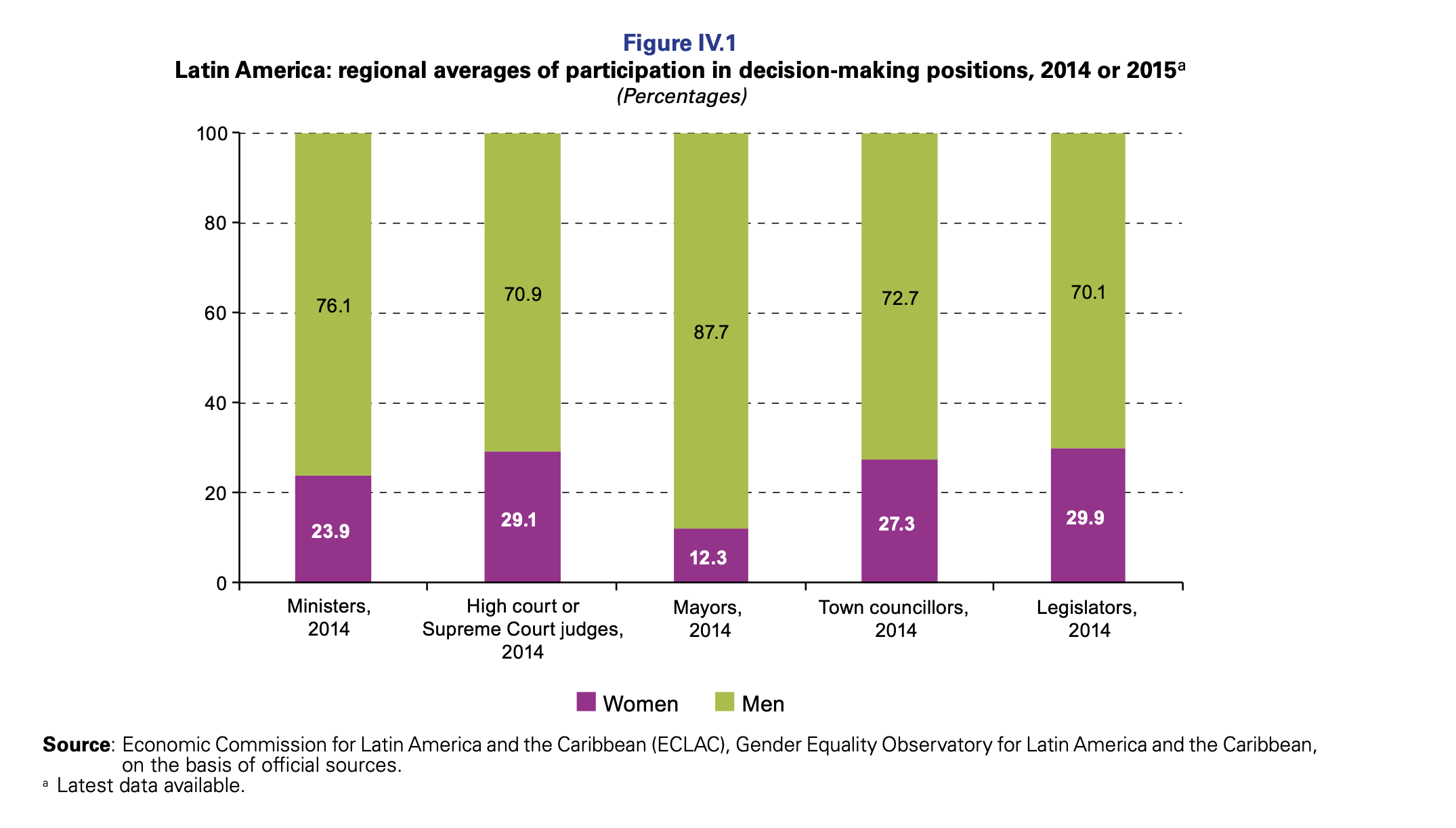

The percentage of women justices in Latin America in 1980 was 3%, but had increased to 19% by 2010.[17] In 1997, Ecuador was the first country in Latin America to adopt a judicial quota that required that at least 20% of superior courts and rosters for lower court judges, notaries, and registrars included women.[18] However, the president of the male-backed committee downplayed the quota law and only 6% of women constituted the court.[19] However, by 2014 women comprised 29.1% of high court or supreme court judges.[20]

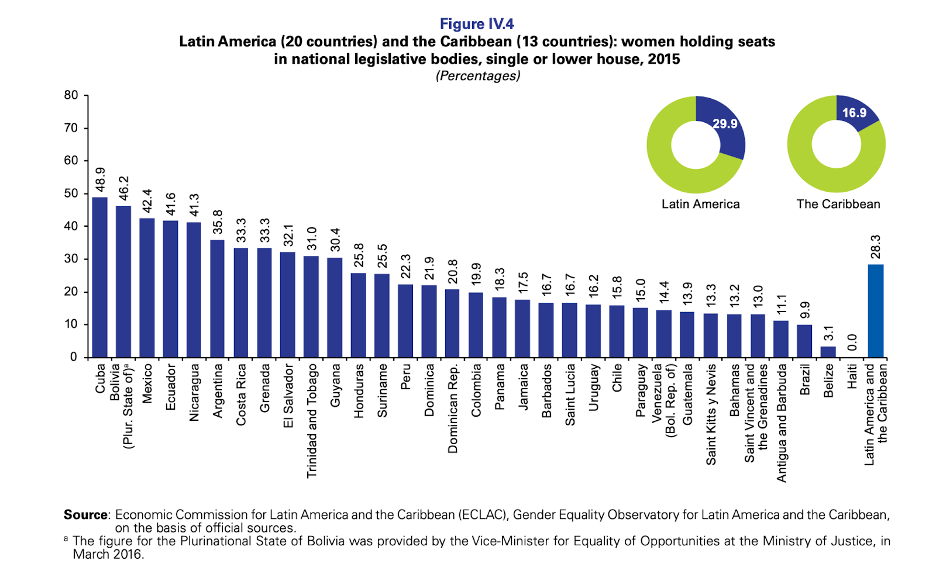

In Latin America in 2014, women were 23.9% of ministers, 12.3% of mayors, 27.3% of town counselors, and 29.9% of legislators. Nicaragua had the highest percentage of women in ministerial cabinet positions (57.1%) while Guatemala had the lowest percentage at 11.8%.[21] Cuba has the highest percentage of women holding seats in national legislative bodies at 48.9%.[22] Regardless, Latin America is still a world leader with regard to the number of seats held by women: 28.3%.[23] On average, the number of female mayors is less than half the number of women ministers, parliamentarians and high court judges. The regional average of female mayors was only 12.3% in 2014. Nicaragua had the highest percentage at 40.1% and was the only country above 30%.[24]

As indicated by statistical analyses of women’s political representation, it’s clear that there has been an increase in women’s political participation in most areas. Since the introduction of quota or parity laws in the 1990s in Argentina, women’s political participation has significantly increased although various political parties and electoral fronts still disregard the law.[25] Out of 33 Latin American Countries, only 16 have established some form of mandatory gender candidacy quotas.[26] Quotas higher than 40% have particularly positive effects on the electoral system (UN-Women, 2015).[27] However there still is a major gender disparity. Women still comprise less than half of legislative bodies in the majority of Latin American countries, and on average less than a third of ministers, judiciaries, mayors, town counselors, and legislators are women. Additionally, women’s mayoral representation is severely lagging behind other political offices. Compared to the progress made with regard to elected office at the national level, women’s participation in local government has advanced at a much slower pace and the resulting policies have been limited. The problems are further emphasized by the fact that these numbers are even lower for afro-descendant and indigenous women.

More Barriers for Women

In a survey of the collective population across 17 Latin American countries, 21% of respondents believed that males are better overall leaders than women.[28] Only 11% believed that men are stronger economic managers than women. Just 3% believed male leaders were less corrupt than female leaders. 30% of the region’s residents believed that women are the most competent managers of the national economy. Over a third of respondents believed that women politicians are less corrupt than their male counterparts. In Chile, despite Michelle Bachelet’s approval rating of over 80%–a rating much higher than her male successor–24% of Chileans believed that men make better political leaders than women. On the other hand, Costa Rica’s woman president Laura Chinchilla had an approval rating of just 26% in 2012. Regardless, Costa Ricans were the most likely citizens living in female-led nations to disagree that males make better political leaders.

Elections create specific circumstances and barriers for women. In the prospect of running for elections, women must contend with the political harassment they may face. The severity of harassment varies. They range from assigning women to unwinnable districts, to failing to provide material or human support, to attacks or threats during campaign periods. In the case of elected women, they may be assigned to commissions or areas of minor importance with limited or nonexistent budgets, face discriminatory treatment by the media, be held to a greater standard for accountability than their male peers, and encounter intimidation, threats, or physical violence against them or their families. In extreme cases, this can include rape or murder. Bolivia is the only country in the region to have passed laws prohibiting political harassment and violence against women.[29]

How to increase political participation

So how can women break the glass ceiling? There have been multiple proposed and imposed approaches to boost women’s numbers in the private sphere. In the case of justices, judicial reshuffles and mandatory quotas have been implemented to potentially increase the amount of representation across the board. However, reshufflings do not always result in a wider diversity of justices, especially when right-leaning parties are in power. Judicial reshuffles with left-leaning parties in power are more likely to result in women in formerly abandoned positions.[30]

Public financing is also a useful method to provide women access to the resources they need to maintain political campaigns, as women tend to be less connected to networks that support political endeavors. Even if financing does not ultimately result in the election of a women official, they at least afford women the opportunity to contest an election. Public financing can also serve as incentives by increasing public financing for political parties that meet specific criteria and also by providing subsidies for parties that support the women’s election campaigns. Sanctions can also be imposed that reduce public financing for parties that fail to meet specific requirements.[31]

Quotas are only a temporary solution to a larger issue. We should strive for gender parity as the ultimate goal and as a permanent governing principle of political activity. The goal of parity is enshrined in the legal system of Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Mexico, and Bolivia.

[1] UN Women, Towards Parity and Inclusive Participation in Latin America and the Caribbean, (UN Women 2021), 7

[2] Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom, (Oxford University Press 2001), 37

[3] UN Women, 43

[4] Ibid

[5] Sen, 191

[6] Sen, 37

[7] Sonia Alvarez et al., “AFTERWORD: Maneuvering the ‘U-Turn,’” in Seeking Rights from the Left (Duke University Press, 2018), 305.

[8] UN Women, 40

[9] Constanza Tabbush et al., “LGBT Rights Yes, Abortion No,” in Seeking Rights from the Left, (Duke University Press, 2018), 94

[10] UN Women, 19

[11] UN Women, 5

[12] ECLAC, Equality and Women’s Autonomy in the Sustainable Development Agenda, (Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2016)

[13] ECLAC, 119

[14] Ester Del Campo, “Women and Politics in Latin America: Perspectives and Limits of the Institutional Aspects of Women’s Political Representation,” in Social Forces, (Oxford University Press 2005), 1703

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid

[17] Ignacio Aranya Araya, Melanie M. Hughes, Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, “Judicial Reshuffles and Women Justices in Latin America,” (American Journal of Political Science, 2021), 65(2) 373-388

[18] Ibid

[19] Ibid

[20] ECLAC, 118

[21] ECLAC, 119

[22] ECLAC, 121

[23] Ibid

[24] ECLAC, 123

[25] ECLAC, 121

[26] Seltzer, 4

[27] UN Women, Annual Report 2014-2015, (UN Women 2015)

[28] Mark Seltzer, “Adversity, Gender Stereotyping, and Appraisals of Female Political Leadership: Evidence from Latin America,” (The Latin Americanist, 2019), 63(2):189-219

[29] ECLAC, 125

[30] Araya et al, 375

[31] ECLAC, 127