11 Poverty as a pipeline to femicide in Honduras- Ilma Turcios

Ilma Turcios

Ilma Turcios

Professor Esther Hernandez-Medina

Gender and Development in Latin America

INTRODUCTION

In the examination of gender-based violence, Honduras stands out in comparison to other countries in the Latin American region. According to a report by The Global Americans, Femicide and International Women’s Rights: An epidemic of violence in Latin America, “the level of violence affecting women in El Salvador and Honduras exceeds the combined rate of male and female homicides in some of the 40 countries with the highest murder rates in the world” (The Global Americans 2021). Violent culture against women is prevalent in countless countries, but it demonstrates a particular concentration in Honduras, with women being victimized at alarming rates.

Honduras, in particular, is distinguished by its small size and population. This makes it a notable point of analysis, given the fact that it has one of the highest femicide rates in the world; in fact, the city of San Pedro Sula is infamously recognized as, “The Murder Capital of the World.” Facts like these beg the question of what exactly explains these alarming rates of violence. With numbers surging in recent years, Honduran authorities have found themselves in a stagnant state, unable to explain what is responsible for the continuous increase of violent crime against women.

This country is distinguished by high levels of poverty with a current GDP of $23.8 billion. Data provided by the World Bank shows that in 2016, around 60 percent of the population lived in poverty and in rural areas, one in five individuals lives in extreme poverty (World Bank 2021). This same report states that Honduras has “the second highest poverty rate in rate in Latin America and the Caribbean after Haiti” (World Bank 2021). These statistics have manifested themselves in the years after the 2009 military coup that ousted Manuel Zelaya from the Honduran presidency.

After this event, poverty rates in the country increased significantly, along with the presence of a heavily militarized culture both socially and legislatively. In the years after the coup, the nation saw a constant destabilization that left development in a stagnant state. This has become apparent through the feminization of poverty–which UN Women notes leaves women with little to no access to the “critical resources” they need to be in equal standing with their male counterparts in terms of economic development (UN Women 2000). Considering the circumstances in which femicide occurs and the specific demographics being victimized, I argue that poverty is a direct pipeline to femicide and other forms of gender-based violence in Honduras. I will assert this by analyzing gendered violence as a composition, governmental idleness, and the feminization of poverty, and how these three characteristics are in direct correlation with high numbers of femicide in the country.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Theoretical concepts

Understanding gender-based violence cannot be done without first exploring its potential causes. These causes, however, cannot be examined without considering the intersections of various identities and attributes of those who are subsequently victimized. Kimberle Crenshaw’s introduction of the idea of intersectionality allows for gendered violence to be viewed from a completely different manner, in which the phenomenon isn’t identified as simply an issue of sex. Intersectionality was coined by Crenshaw to describe how gender, race, class, and other identifying factors overlap with one another. In the context of gendered violence, this idea spreads the lens in which I will develop my argument; as opposed to defining femicide simply as an act in which women are killed or brutalized based on their sex, I seek to expand on what exactly is a responsible gateway to what we see in Honduras. In her article, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color”, Crenshaw argues that being a woman and a person of color have historically been viewed as separate issues, when in reality, “the violence that many women experience is often shaped by other dimensions of their identity” (Crenshaw 1991: 1242). Crenshaw’s framework relates to the intersections of race and gender; however, I intend to argue that this same principle applies in the context of femicide in Honduras and the feminization of poverty.

The analysis of class structures is vital to making the connection between economic factors and the violence these factors lead to. Alejandro Portes and Kelly Hoffman define class structures as, “discrete and durable categories of population characterized by differential access to power-conferring resources and related life chances,” in their article, “Latin American Class Structure” (Portes and Hoffman 2003: 42). In short, they seek to “reintroduce an explicit class framework in the analysis of contemporary Latin American societies, providing empirical estimates of its various components, and examining how they have varied across countries over time” (Portes and Hoffman 2003). In the context of Honduras, the life chances of individuals, especially women, are drastically affected by the economic shortcoming seen across the country, like income inequality, lack of opportunity, etc. This idea shares a direct connection with Portes’ and Hoffman’s argument that despite progression, there is still “a persistent concentration of wealth in the top decile of the population” (Portes and Hoffman 2003). I will apply this same idea to my assertions, but instead, I will explore how these economic factors relate to femicide and other forms of gender-based violence.

In chapter one of, Women’s autonomy in changing economic scenarios, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), asserts that equality–not only in terms of economics but also factors like the exercise of rights–is central to development (ECLAC 2020). The idea that, “this is the region [Latin America and the Caribbean] that remains the most unequal in the world, with still significant levels of poverty and large sections which are highly vulnerable to the economic cycles” (ECLAC 2019a: 17), is crucial to understanding the economic disparities seen in Honduras despite years of progress. The introduction of the concept of autonomy–“women’s capacity to take free and informed decisions about their lives” (ECLAC 2020: 17)–allows deeper insight into how socioeconomic factors relate to a lack of autonomy in the lives of women. In the chapter, ECLAC notes that Latin America and the Caribbean have introduced institutional initiatives tasked with facilitating gender and equality and women’s autonomy (ECLAC 2020: 114). However, despite these efforts, little tangible change has been noted in the region; utilizing these concepts, I will explore how this can be observed in Honduras, as one of the potential paths to violence.

A significant portion of Honduras’, as well as the rest of Latin America’s economic difficulties, can be traced back to international factors. Eduardo Galeano presents this idea in, “Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent”. In his introduction, Galeano argues that Latin America exists at the service of others. He notes that Latin America’s underdevelopment is a significant result of capitalist development, in which rich countries profit more from the consumption of certain goods than the latter does from producing them (Galeano 1974: 11). This observation applies to Honduras, as noted through the years of exploitation of its native resources for the gain of rich foreign countries, with little regard for the implications of such practices. As Galeano notes, “perpetuation of the current order of things is perpetuation of crime” (Galeano 1974: 18). I will apply this same argument to Honduras, by exploring how international production has affected underdevelopment in the country, and the socioeconomic inequalities this results in for women affected by violence.

Analytical questions

It is crucial to view violence against as a system rather than a singular act. In her article, “Complicating Notions of Violence: An Embodied View of Violence against Women in Hondutas”, Maaret Jokela-Pansini, examines how heavily militarized countries like Honduras uphold patriarchal values that determine who should be protected, and from what they should be protected (Jokela-Pansini 2020). I will utilize Jokela-Pansini’s three concepts of violence–the relationship between militarization and the normalization of violence against women, women’s bodies becoming “battlefields through structures and institutions such as militarization” (Jokela-Pansini 2020), and how gendered violence is linked to socioeconomic processes–to examine what is responsible for the heavily militarized culture and violence in Honduras.

In their article, “The Architecture of Femicide,” Cecilia Menjívar and Shannon Drysdale Walsh explore gender-based violence against women in Honduras, and the actions that result in this violence. They interpret femicide as a result of “actions and inactions” by the Honduran state since the coup of 2009 (Menjívar and Walsh 2017). They establish Honduras’ economic disruption as being enacted by the coup that took Manuel Zelaya out of power by utilizing an “extreme-case” framework that identifies how normalization works in the relationship between the context of violence and acts of extreme violence and the liberty to do so–a sort of cause-and-effect approach (Menjívar and Walsh 2017). In other words, they examine femicide as an end effect, and its causes stemming from governmental negligence. Despite the fact that this article does not address the question of how poverty is in direct correlation with femicide, I will argue that it does in fact relate to economic factors by citing the governmental inactions that lead to economic disparities, and thus, leaving individuals to turn to other methods of acquiring money, which is often violent.

To understand the relationship between violence and poverty, the economic fallbacks of Honduras must be examined. Rachel Lomot’s article, “Gender Discrimination: A Problem Stunting Honduras’ Entire Economy,” explores poverty as a gendered issue (Lomot 2013). I will utilize Lomot’s methodology of declining GDP statistics, adult literacy rates, and women labor participation rates (Lomot 2013) to suggest how these factors serve as a foundation for femicide in Honduras. Additionally, Lomot cites the futility of legislation meant to promote gender inequality which directly relates to growing numbers of femicide rates in the country.

MAIN FEATURES

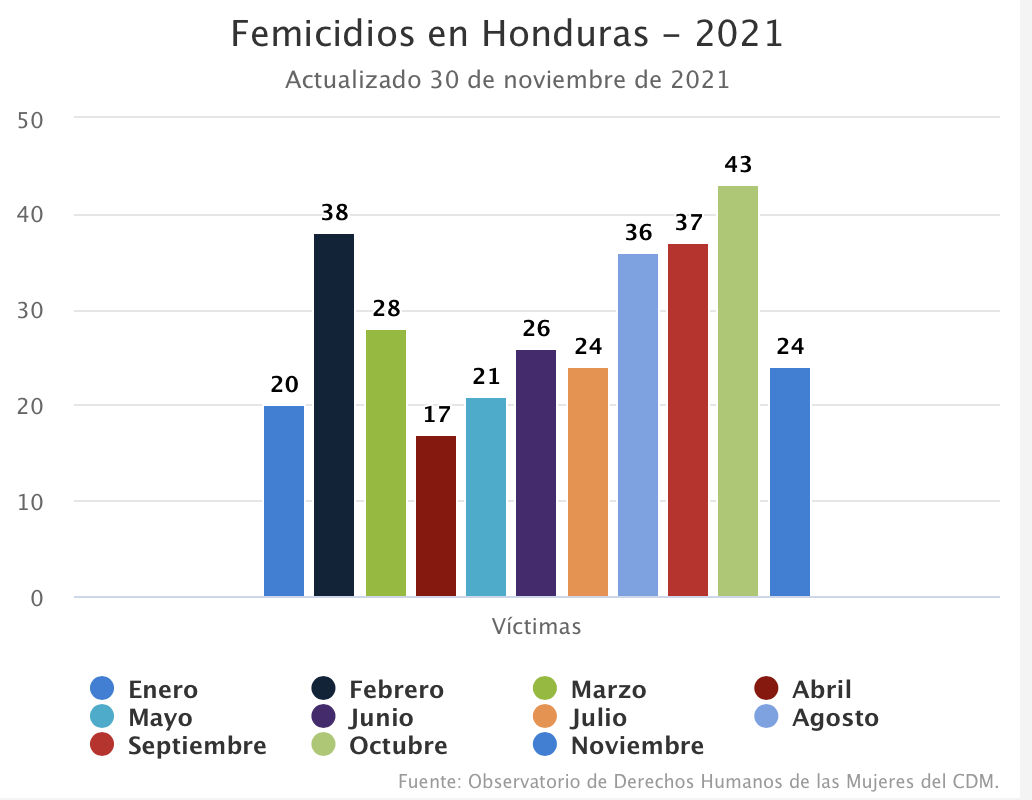

Gendered violence in Honduras has reached new heights, with record-breaking numbers of reported cases of femicide. In 2021 alone, as of November, there have been 314 reported cases of violent deaths for women (see Figure 1)–not to mention the large number of cases that often go unreported, which suggest that these numbers are far larger than any communication media suggests (Centro de Derechos de Mujeres 2021). Various factors are responsible for this lack of reporting. For the most part, many fear the potential repercussions of reporting instances of violence, which in most cases takes the form of further acts of violence at the hands of perpetrators. These perpetrators will almost always be men, and oftentimes, violence occurs within domestic relationships.

Figure 1. Femicides in Honduras – 2021

Since femicide was formally recognized as an act that could be criminalized in 2013 by Honduran legislators, only 15 cases have actually resulted in conviction, according to Vienna Herrera’s article, “Femicide in Honduras: women dismissed by their own government “(Vienna 2020). “These are cases brought before a justice system that is poorly trained in gender issues, and recent legislation has reduced the penalties for crimes of violence against women,” says Vienna. Facts like these suggest a stark connection between the lack of opportunity in the country, and the resulting violence: a sort of cause-and-effect relationship that I will explore via Menjívar and Walsh’s methodology utilized in their article, “The Architecture of Femicide.”

The feminization of poverty is something that concerns a significant portion of the world’s women, with this demographic being extremely disadvantaged in economic terms when compared to men. This phenomenon is defined as “limitations in access to basic services, resources, economic opportunities, and decent employment (livelihoods)” (Care and UN Women 2020: 1). Poverty, therefore, takes on a new meaning. Previously thought of as simply an economic issue, examining this as a gendered component of development allows for a more intersectional analysis of high poverty rates like those seen in Honduras. In 2019, it was estimated that 14.8 percent of the country’s population earned less than 1.90 U.S. dollars per day, and about half of the population earned less than 5.50 U.S. dollars per day, making it the country with the second-highest poverty rate in Latin America and the Caribbean after Haiti (World Bank 2021). Additionally, “gender gaps in job losses in Honduras are also among the highest in LAC (Latin America and the Caribbean)” (World Bank 2021). In precise terms, Honduras has a gender gap of 27.8 percent (Care and UN Women 2020: 1). The feminization of poverty can be considered to be a result of “the gaps faced by the female population in terms of income in the labor market and not having access to job security and social protection,” which leaves women especially vulnerable to gender-based violence as a result of the many barriers to their economic autonomy (Care and UN Women 2020: 10).

The focus of this paper will rely on the analysis of gendered violence in Honduras in terms of an economic perspective. In essence, I will be asking the question of how poverty and lack of opportunity in the realms of economics and labor serve as a conduit for violence. In this context, violence should be viewed as the product of several chains of events that ultimately lead to it. For example, the Honduran government practices several inactions in the way it enacts and carries out legislation. A lack of action can be owed to unsustainable wages for government workers that create little incentive to work, and the absence of education on gender for legislators does not allow for cases of femicide to be properly investigated. In this same way, these occurrences are tied to other chain of events that lead to the femicide which is then investigated by government officials. These chains of events include instances like individuals under the poverty line turning to dangerous occupations like sex work which often leads to them being victimized.

Global events like the COVID-19 pandemic have only worsened the economic conditions of the country with occurrences like government-mandated curfews, massive loss of employment, and two devastating hurricanes that left many displaced. As of August of 2020, “one in four companies [had] suspended its employees,” which is extremely significant for a country where 900,000 individuals depend on under 750,000 businesses for employment (KfW Development Bank 2020). This same article, “Honduras: COVID19 in one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change,” notes that 60 percent of Honduras’ population lives in poverty, and as estimated by the country’s Central Bank, this number could rise to 75 percent (KfW Development Bank 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic shares a critical relationship with violence in the nation. In the months ranging from March 15th, 2020–the date national curfews were established at the start of the pandemic–to December 31st, 2020, there were 229 reported violent deaths for women across Honduras. Out of the reported 229 cases, the majority–162 precisely–were carried out by someone the victim did not know. This is notable in the way femicide is identified as many reporting agencies define these crimes only in the context of domestic violence, failing to account for other circumstances where women are victimized. This is often responsible for underreporting, (Centro de Derechos de Mujeres 2020).

Cases of femicide are often met with little to no media attention, further normalizing the male chauvinistic culture found across Honduras. There exist only few cases in which gender-based violence has received national and international attention. On November 13th, 2014, Maria Jose Alvarado, who was Miss Honduras at the time, and her sister Sofia Alvarado were brutally murdered by the latter’s boyfriend after an argument. After six days of extensive searches led by the Honduran military, that even extended across the Guatemalan border, their bodies were found partially buried along a river. Plutarco Ruíz was arrested for the murders which he noted were provoked by a jealous rage after he saw his partner dancing with another man. According to police official Vicente Reyes, the extent to which the search for Alvarado was carried out, is telling of Honduras’ government and culture. Even Alvarado’s mother notes that had it not been for who her daughter was, they would have never received justice (Jo Tuckman, The Guardian 2014).

Unlike Alvarado, countless other women have been overshadowed with their abusers receiving little to no punishment for their crimes. Despite efforts by activist groups and legislators, femicide rates are only on the rise. Rather than analyze this phenomenon from a cultural perspective I will focus on how the extremely high levels of poverty Honduras has seen throughout the years, has affected violence against women. I will argue that poverty serves as one of the principal catalysts for violence.

ANALYSIS

Gendered violence as a complex systemic structure

Violence against women can be characterized as an extensive system of different actions. Completely analyzing violence requires visiting its roots, which in the case of Honduras, like many other countries of the world, lies in machismo, or male chauvinism. Machismo is the manifestation of aggressive masculine pride, and it is often rooted in the idea that men are superior to women in virtually all aspects. In some countries, machismo is especially prevalent as seen in many Latin American and Caribbean nations, like Honduras. This belief is something that could be traced back years in Honduras’ history, even before the 2009 coup although it became much more prevalent in the years following this military intervention. In fact, is something with which many individuals are raised, making it something virtually ingrained into this society, often being seen notable in its various spheres. The prevalence of machismo is obvious in Honduras, with women being systemically being placed at a significant disadvantage when it comes to men in education, legislation, politics, labor, etc.

Honduras is facing what is dubbed as an “epidemic of femicides” (teleSUR 2018). Oftentimes, machismo is noted as “one of the leading causes behind the killings of women” (teleSUR 2018). Although this is true, assertions like this one sometimes tend to oversimplify how violence plays out, characterizing it as something strictly between a perpetrator and a victim with little interconnections. Yes, it is true machismo is extremely prevalent in the region and it is one of the catalysts for femicide; however, it must be understood as a singular part, not as the whole image. It is for this reason that violence must be examined through a wider lens because “to address violence it is necessary to also address the underlying discrimination factors that give rise to and exacerbate [it]” (teleSUR 2018).

Violence in Honduras is often viewed as a singular act between a perpetrator and a victim with both parties often being heavily polarized. Acts of violence across the country are never considered to be interconnected, leading to the misconception that this occurs at an exclusive level with “self-evident” causes (Jokela-Pansini 2020). However, violence acts more “as a complex system instead of a norm located in certain places” (Jokela-Pansini 2020). This raises the question of how gendered violence is characterized and exactly what social practices are linked to it: something common in countries replete with significant military cultures, like Honduras.

In 2009, the country saw its fourth coup d’etat that ousted PLH (Partido Liberal de Honduras or Liberal Party of Honduras) president, Manuel Zelaya from power. Zelaya, who in his time as president, shifted the country’s political agenda towards a more left-leaning one, was clandestinely taken from his Tegucigalpa home by the Honduran military and forced into a nearly two-year exile period. Under de facto president, Roberto Micheletti’s coup government, the country saw a massive increase in military action after national protests demanded Zelaya’s return. In her

, ‘Who rules in Honduras? Coup’s Legacy of Violence, Annie Murphy says, “they [the military] began arresting, beating, and even killing anyone who protested against the new government” (Murphy 2012). Despite Zelaya’s lack of popularity as president many hold that “illegally ousting him has had huge repercussions” (Murphy 2012).

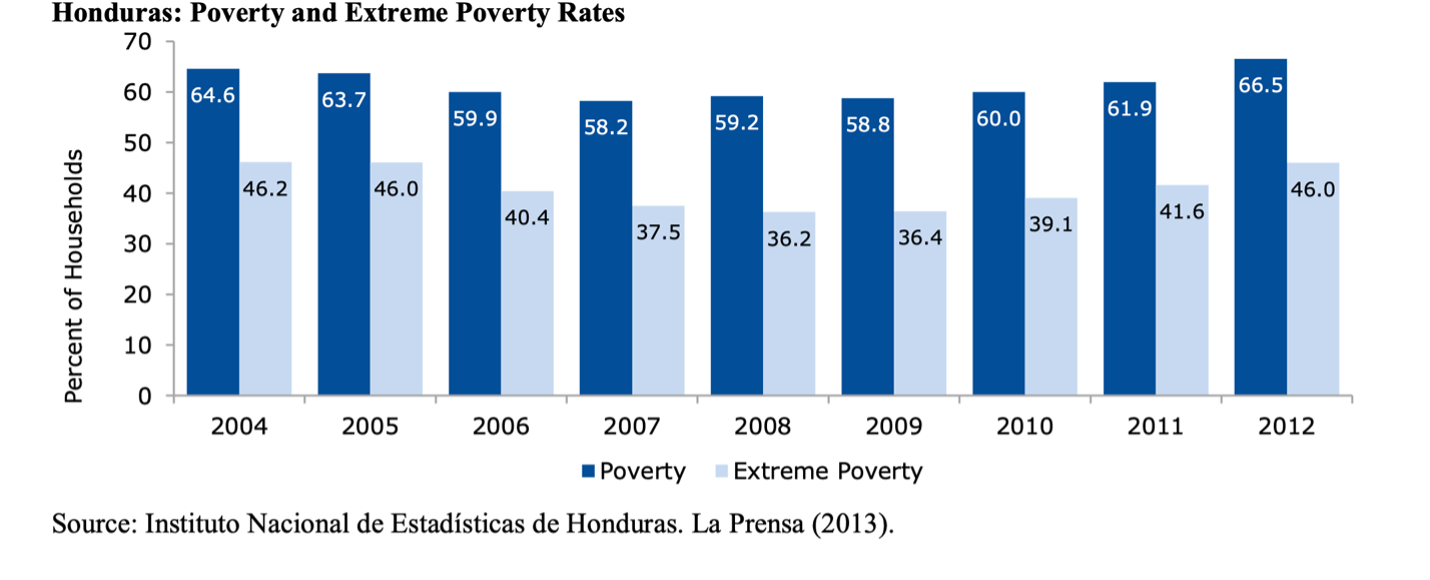

Figure 2. Honduras: Poverty and Extreme Poverty Rates

The repercussions of the illegality of this United States-backed coup have taken the form of immense levels of poverty and increased violence, especially against vulnerable demographics–i.e. women, members of the LGBTQ+ community, journalists, lawyers, BIPOC, etc. Notably, in the first month after the coup took place, femicide rates rose by 60 percent (Kelly 2011).

A 2013 Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) report by Jake Johnston and Stephen Lefebvre, Honduras Since the Coup: Economic and Social Outcomes, shows substantial economic and social decline noting that “while some of [it] was initially due to the global recession that began in 2008, much of it is a result of policy choices.” Contrary to Zelaya’s low levels of popularity in the political and social realms, “poverty and extreme poverty rates decreased by 7.7 and 20.9 percent respectively during [his] administration” (Johnston and Lefebvre 2013). Contrastingly, in the first two-three years after the 2009 coup, “the poverty rate increased by 13.2 percent while the extreme poverty rate increased by 26.3 percent” (Johnston and Lefebvre 2013). Reviewing the data on the graph (see Figure 2), suggests that there is a stark connection between rising levels of poverty and the 2009 coup, emphasizing the fact that rather than increase governmental prosperity, this event–which under Honduran law was unconstitutional–is responsible for a large part of the instability now seen across the country.

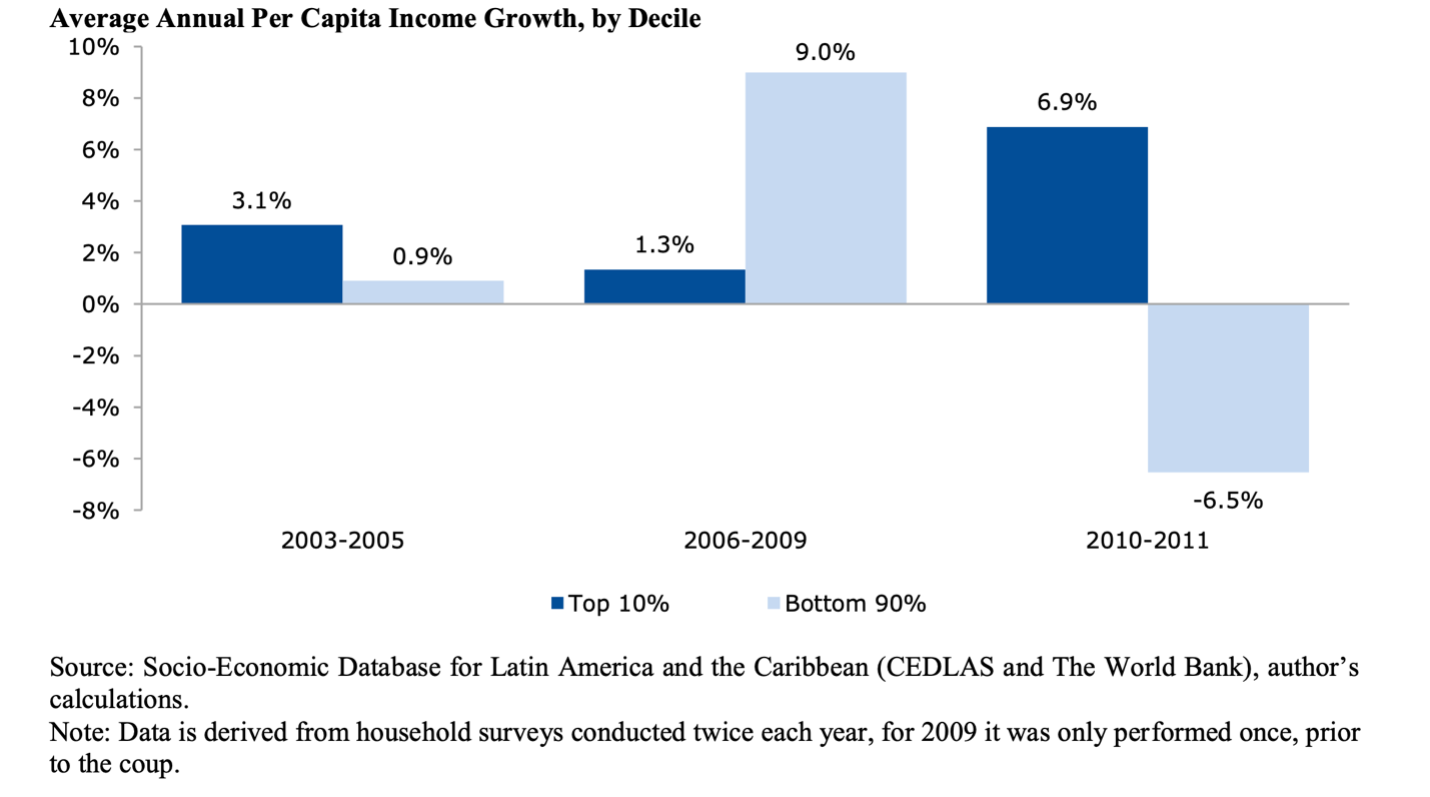

Figure 3. Average Annual Per Capita Income Growth, by Decile

This background allows for femicide in the region in the context of heavy militarization to be better understood, and with it, Jokela-Pansini’s concepts of violence. Firstly, the normalization of violence is best owed to the military-heavy culture–that rules almost all realms of society, not just the political one (i.e. the ideals that result from this, like the infamous concept of machismo or male chauvinism, have permeated into the way social norms are followed)–that resulted after the 2009 coup. This means violence is characterized as, “a constant feeling of having one’s rights violated and experiencing that violation,” by numerous interviews given to women in the region (Jokela-Pansini 2020). As aforementioned, after the 2009 coup, Honduras saw significant rising levels of poverty (see Figure 3 which shows a concentration of wealth at the top 10 percent of the country [Johnston and Lefebvre 2013]) and violence. To be precise in the question of violence against women, Honduras has “the highest per capita murder ratio in the Western hemisphere. Homicides, feminicides, political persecution, disappearances, and targeted assassinations have escalated since the 2009 coup,” according to Jeannette Charles in her article for teleSUR, “Violence in Honduras Since the 2009 Coup”, (Charles 2014). As of 2014, the female murder rate in the country is 14.6 per 100,000 individuals and in terms of time, a woman is murdered every 36 hours (Charles 2014). For a country of this size, these numbers are extremely significant, and they are only on the rise.

Secondly, women’s bodies become “battlefields through structures and institutions such as militarization, restrictions on women’s reproductive rights, and domestic violence” (Jokela-Pansini 2020). Although this notion takes a somewhat ideological take on the issue of femicide, there are concrete examples that support the idea. Reproductive rights are a prime example of this. Today, Honduras remains one of the six countries where abortion is illegal under all circumstances (Guttmacher Institute 2018). In this way, women become subjected to processes in which their bodies are victimized. In the context of abortion, this means undergoing unsafe procedures that often result in serious health complications like, “incomplete abortion, blood loss, and infection” (Guttmacher Institute 2018). Additionally, women’s bodies become battlefields by governmental actions as well. Currently, “Honduras’ criminal code imposes prison sentences of up to six years on people who undergo abortions and medical professionals who provide them” (Human Rights Watch 2021). Consequently, in some ways, women are placed into a sub-categorization of almost being less-than-human, not being able to exercise their basic human rights, and their lives being less valued than those of their male counterparts. Violence takes on a new meaning, not being exclusively a physical act, but a limitation on not only women’s bodily autonomy, but their legislative one too (ECLAC 2020).

Thirdly, violence shares an extremely close relationship with social practices in Honduras. This takes place in the form of foreign monetary and military aid under the premise of development in the country. A 2020 report by Kaitlyn Gilbert for The Borgen Project gives various examples of how foreign aid was utilized in Honduras in 2018. Some of the most notable statistics include 6 million dollars on legislation meant to uphold human rights, 25 million dollars on government assistance programs, 24 million dollars on education, and 25 million dollars on crime prevention (Gilbert 2020). Despite the country receiving these funds, their allocation remains a subject of controversy with about 48 percent of the population still living below the poverty line (Jennifer Philipp et al 2020). Governmental corruption under president Juan Orlando Hernandez–who was exposed to having connections with the drug trade in the region–reached incredible heights during his tenure, turning the country into a narco-state, with two powerful drug lords testifying that Hernandez provided them with immunity and protection in exchange for money (García 2021).

In the context of foreign aid, this is extremely significant, as the country has received significant funds meant to promote development, and yet little to none of the population has seen what these funds could yield. Violence remains at an all-time high, and it is only increasing. Although this leaves most of the Honduran populace susceptible to violence, women are especially vulnerable.

Governmental idleness

In a country where a large portion of the population lives under the poverty line, there is little incentive for governmental action against gendered violence. Menjívar and Walsh turn away from the role of economic disruption when analyzing femicide in Honduras. Instead, they “examine [how] the actions and inactions of the state have served to amplify violence in the lives of Honduran women…[moving] beyond income disparities to highlight inequalities…where the state is a key player in perpetuating and reinforcing unequal access to justice and rights” (Menjívar and Walsh 2017). However, the cause-and-effect relationship cited by the authors cannot exist without accounting for economic aspects.

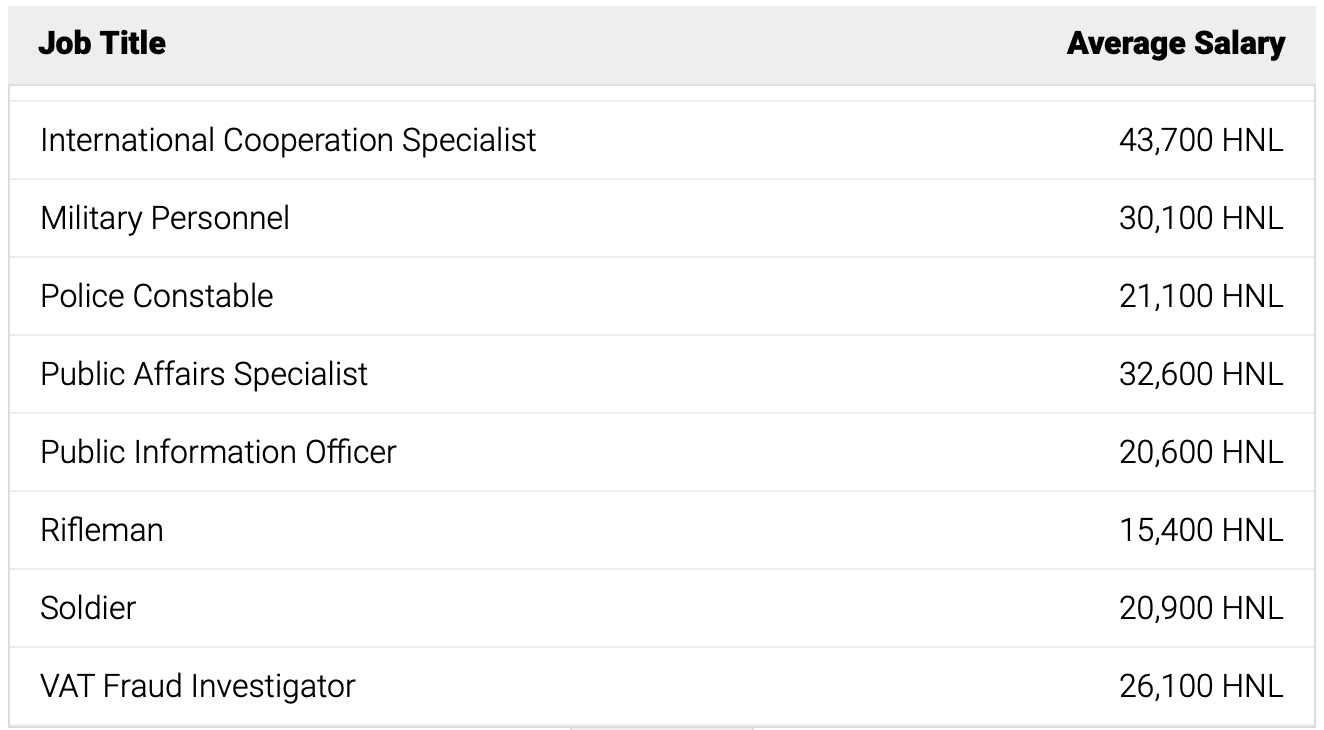

Figure 4. Government and Defense Average Salaries in Honduras 2021

For example, the average minimum wage for most of the workforce in Honduras ranges from 22.44 lempiras per hour, to 36.68 lempiras per hour (93 cents per hour to 1.52 dollars per hour): a barely livable wage (Minimum-Wage.org 2021). Notwithstanding higher levels of education or occupational skills, many individuals still earn less than what their skills are worth. Governmental employees, like police officers or government officials, are not exempt from this as noted in Figure 4 which documents the monthly salaries of different governmental occupations. For example, the monthly salaries for armed forces officers, army officers, soldiers, and public affairs specialists are around 929, 937, 870, and 1,358 U.S. dollars respectively (using the conversion of 24 lempiras = 1 U.S. dollar).

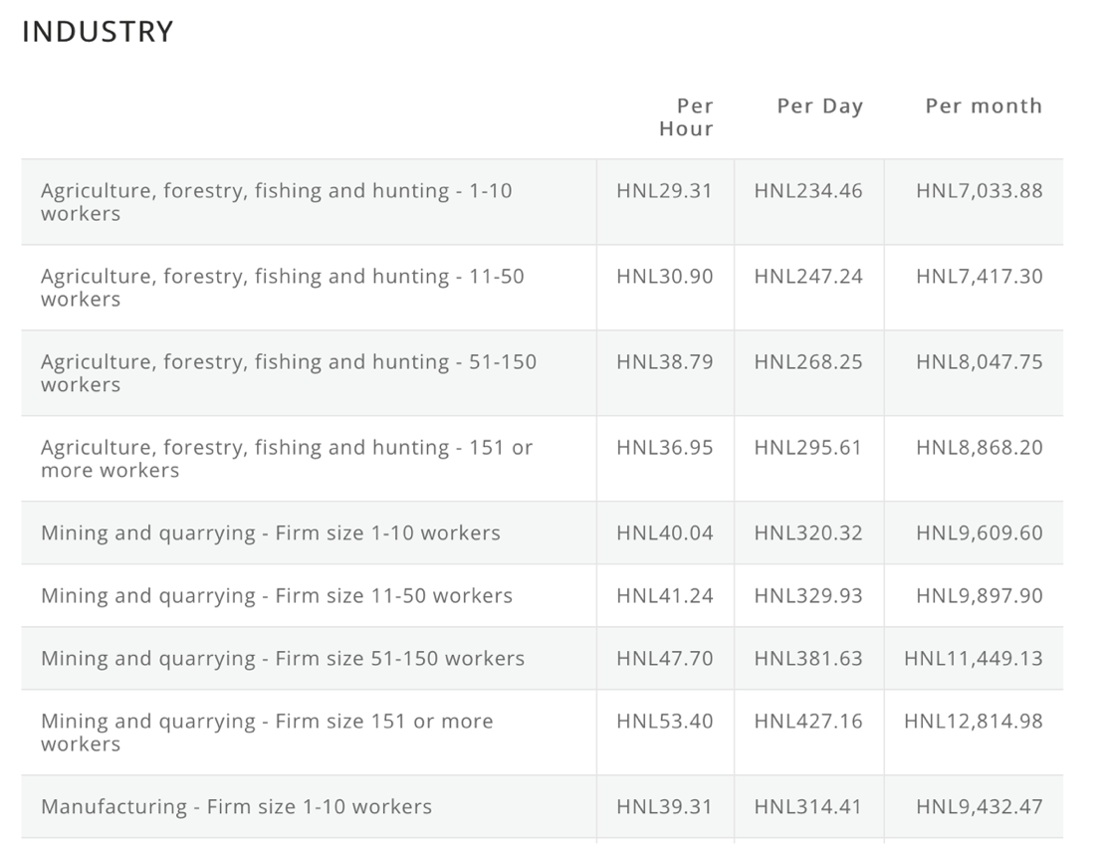

Figure 5. Average Monthly Salary Per Industry in Honduras

For non-government employees, the average pay for work is even less (see Figure 5). For example, the monthly salaries for the average agricultural, construction, and retail worker are 335, 483, and 541 U.S. dollars respectively (using the conversion of 24 lempiras = 1 U.S. dollar).

These numbers suggest that governmental inaction, in terms of extremely low wages–which government officials themselves are subjected to as well–serves as a gateway to violence. A common factor in many cases of femicide is that oftentimes the perpetrator carries this crime out for some sort of financial gain. For example, in many parts of the country, killing a woman in a murder for hire costs around 60 U.S. dollars (Galdos 2015). Taking into account just how little individuals earn on a daily basis, many turn to alternative–often dangerous–ways of earning money quickly. Additionally, given the prevalence of machismo culture in the country, practices like these are more than likely to be overlooked given that women are thought to be less than men, and the government itself turns a blind eye to these occurrences in a perpetual cycle of inactions. The “systemic indifference” demonstrated by police is one of the many factors that allow for femicide to become as widespread as it has in Honduras (Kelly 2011). In short, economic disruption at the hands of the government’s idleness drives individuals towards violence, and in the end, it further weakens the “life chances” of women in the region (Portes and Hoffman 2003): “When we have a femicide case, it’s because the government has failed to fulfill its prevention role. It has been unable to provide the necessary conditions to protect women, and a woman has lost her life as a result of this ineffectiveness” (Vienna 2020). The answer to the question of this rampant ineffectiveness lies within the economic foundations of the country itself which the government is responsible for.

Poverty as a gendered issue

The feminization of poverty is a phenomenon that is especially prevalent in Honduras. Women have been historically isolated from the workforce, not for a lack of skill, but for a heavy male chauvinistic culture that is ingrained into the way the country operates. According to Lomot’s 2013 article, Honduras has “an unemployment rate of 40.7 percent” (Lomot 2013: 15). In terms of Honduras’ economy, women can be a useful asset towards the workforce, as in the past they have shown to be more than capable of maintaining unpaid work, like childcare and home care.

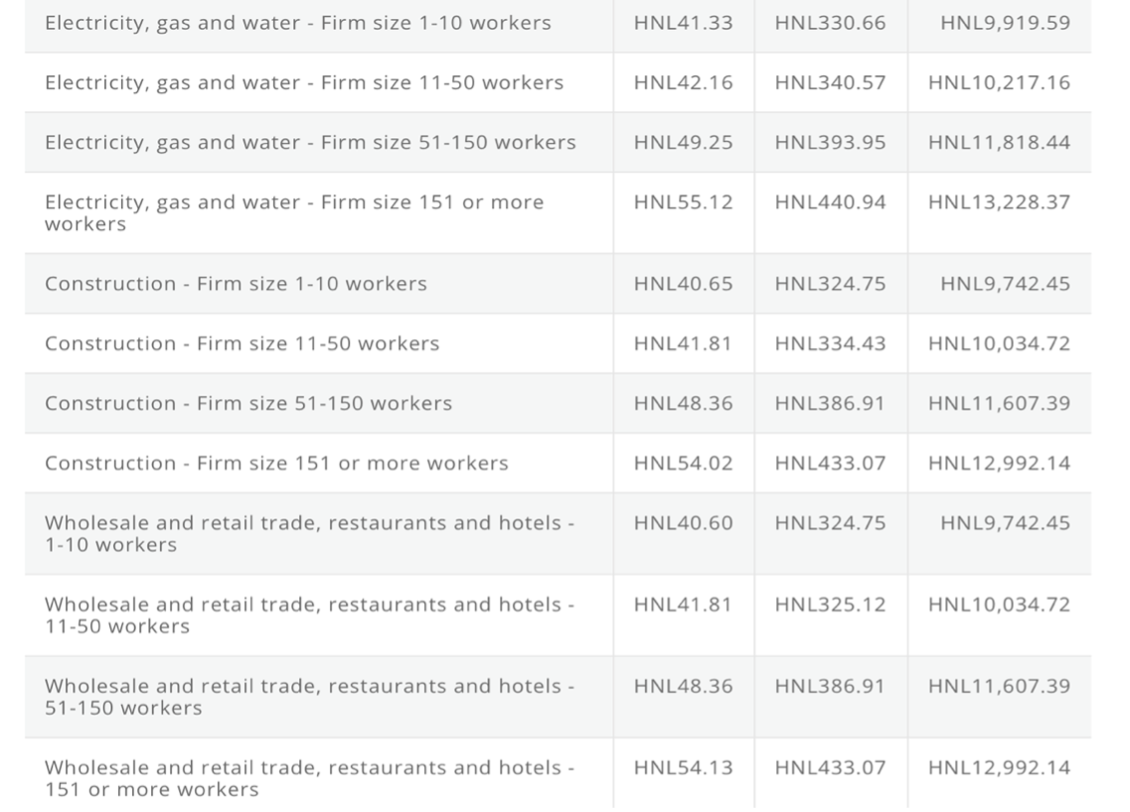

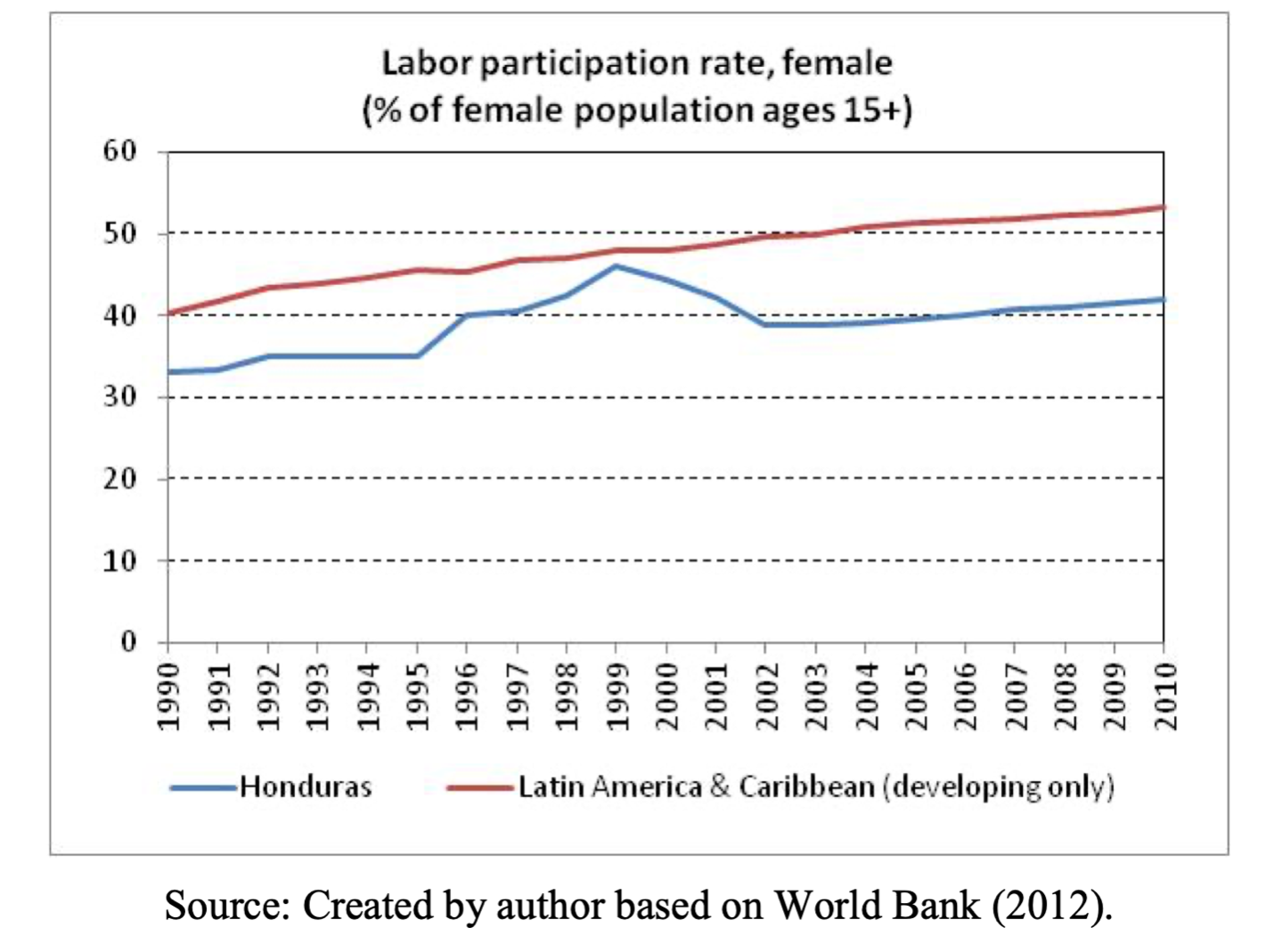

Figure 6. Female Labor Participation Rates in Honduras

When compared to Latin America and the Caribbean, Honduras has historically fallen behind in labor participation rates for women. It only briefly peaked in 1999, before declining until 2002, and plateauing in 2003 and onward, now averaging at around 40 percent (see Figure 6). This can be owed to lack of opportunity, lack of education (as suggested by Honduras’ especially low adult literacy rates compared to the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean, of around 85 percent [Lomot 2013: 18]), and lack of occupations. Numbers like these demonstrate the extent to which women are systemically excluded from the economy, emphasizing the presence of the feminization of poverty in the country. It also demonstrates how women’s different autonomies function in the understanding of violence, which in this case is economic autonomy. However, “the interaction between macroeconomic, production…,employment policies…and the eradication of violence against women must be analyzed in a move to overcome these challenges [inequality] as a whole” (ECLAC 2020). That is to say, considering the economy in the context of how it affects women, also requires paying close attention to the other forms of autonomy women can practice.

Oftentimes women will turn to clandestine occupations like sex work as a means of earning a living. According to a 2014 article by Amnesty International, “for sex workers, the risk of violence is multiplied many times over” (Amnesty International 2014). This brings forth the question of what exactly is responsible for women finding themselves in situations in which they could potentially be victimized. The same economic practices that are responsible for such a violent culture, are the ones that place women in these situations in which they must find dangerous means of making a living. In the example of sex work, despite this not being explicitly prohibited under Honduran law, and thus implying its legality, there also exists no legislation to protect the rights of these individuals. This leaves women extremely vulnerable, and even more so those belonging to the LGBTQ+ community. In 2014, in less than one month alone, “at least five sex workers were murdered in a city of roughly 900,00 residents (San Pedro Sula)” (Amnesty International 2014). If not outwardly murdered, women are often victims of sexual abuse, falling victim to violence through practices like sex trafficking. This chain of events is one of the many commonalities that start with poverty and end in femicide.

Another reason for the economic lack of autonomy that contributes to women’s vulnerability to violence is that within the occupations women do have access to, they are extremely disadvantaged. For example, across most career fields in the region, men are making 9 percent more than women are for the same jobs (Salary Explorer 2021). This is responsible for especially low labor participation rates, as women seeing little to no viable work prospects, simply opt-out of joining the occupations they do have access to. This brings forth the question of how this could be remedied in the pipeline of poverty to violence. Doing so requires looking at the intersectionality of poverty and femicide (Crenshaw 1991). Femicide cannot be analyzed without accounting for the various intersecting attributes that characterize it, which in the context of my argument is poverty. In some cases, women being detached from the economy puts them in positions in which femicide becomes an impending danger in their lives, but violence itself also keeps women out of the workforce, leading to the acceptance of this act as a norm.

CONCLUSION

Today, femicide has become a norm in Honduras, with many individuals–especially women–simply accepting it as part of their reality. Inaction at the hands of the government has facilitated the way these crimes are carried out, almost molding it into a system of normalization that prompts little to no consequence. The principal issue addressed was the lack of economic autonomy women face in Honduras, which ultimately places them in dangerous positions where violence becomes a probable outcome. Despite this being a significant aspect of the issue that Honduras–along with countless other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean–faces, it also prompts the question of what more can be done.

Fully addressing the phenomenon of gender-based violence in Honduras requires dismantling the roots from which it grows. Economic autonomy should be analyzed not as a complete solution–as this has clearly failed in the past as seen in failed initiatives to promote economic equality–but as the first step to promoting an anti-violent agenda. That means, going beyond demands for full economic autonomy and presenting multiple solutions to the rampant problem seen in Honduras. As noted in my argument, economic disparities that resulted after the 2009 coup were a substantial component of the violent culture present in the nation, but there are other present issues to address as well.

For one, as noted in Jokela-Panisni’s argument, women’s bodies become “battlefields” at the hands of the institutions that, in theory, are intended to uphold their rights. Beyond economic autonomy, one must also consider bodily autonomy. Honduras is a country where women have little to no control over what they can or cannot do to and with their bodies, be it for choice or for health. A prime example of this can be noted in the total ban of abortion in the country. In this way, one must analyze how violent crimes against women could truly be prevented if women presently have no jurisdiction over their bodies; therefore, emphasizing that this is something that must also be addressed.

Today, the prospect of change seems to be ever so slightly more accessible. Recently, the country has voted in its first female president–Xiomara Castro–who aims to shift the country’s policy to focus more on women’s fundamental rights. In specific, she seeks to overturn legislation that poses limitations on women’s bodily autonomy. This fact provides a standing point for bringing forth more potential solutions to femicide in Honduras.

Sources

Average salary in Honduras 2021. The Complete Guide. (2021). Retrieved November 30, 2021, from http://www.salaryexplorer.com/salary-survey.php?loc=96&loctype=1.

Care and UN Women. (2021). Rapid gender analysis in Honduras: An overview in the face of covid-19 and ETA / Lota – Honduras. ReliefWeb. Retrieved December 19, 2021, from https://reliefweb.int/report/honduras/rapid-gender-analysis-honduras-overview-face-covid-19-and-eta-lota

2020. Centro de Derechos de Mujeres. (n.d.). Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://derechosdelamujer.org/project/monitoreo-2020/.

Charles, J. (2014, July 17). Violence in Honduras since the 2009 coup. teleSUR English. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.telesurenglish.net/analysis/Violence-in-Honduras-Since-the-2009-Coup-20140717-0132.html.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

ECLAC. (2020). Annotated index of the position document of the fourteenth session of the Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean “women’s autonomy in changing economic scenarios”.

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. (2020, March 26). Gender equality and women’s autonomy must be at the core of the new development model that the region urgently needs: ECLAC. Press Release | Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Retrieved December 20, 2021, from https://www.cepal.org/en/pressreleases/gender-equality-and-womens-autonomy-must-be-core-new-development-model-region-urgently

Femicide and International Women’s Rights. Global Americans. (2017, July 13). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://theglobalamericans.org/reports/femicide-international-womens-rights/

Galdos, G. (2015, February 3). Honduras: Where women are killed for $60. Channel 4 News. Retrieved December 20, 2021, from https://www.channel4.com/news/honduras-where-women-are-killed-for-60

Galeano, E., Belfrage, C., & Allende, I. (2010). Open veins of Latin America: Five centuries of the pillage of a continent. Three Essays Collective.

García, J. (2021, March 22). Honduras rocked by Hurricane of narco-politics. EL PAÍS English Edition. Retrieved December 19, 2021, from https://english.elpais.com/usa/2021-03-22/honduras-rocked-by-hurricane-of-narco-politics.html

Government and defence average salaries in Honduras 2021. The Complete Guide. (2021). Retrieved November 29, 2021, from http://www.salaryexplorer.com/salary-survey.php?loc=96&loctype=1&job=30&jobtype=1.

Herrera, V. (2020, December 12). Femicide in Honduras: Women dismissed by their own government. Contra Corriente. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://contracorriente.red/en/2020/08/08/femicide-in-honduras-women-dismissed-by-their-own-government/.

Honduras minimum wage rate 2021. Federal and State Minimum Wage Rates for 2021. (2021). Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.minimum-wage.org/international/honduras.

Honduras: Attack on reproductive rights, marriage equality. Human Rights Watch. (2021, January 23). Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/01/23/honduras-attack-reproductive-rights-marriage-equality#.

Honduras: Covid19 in one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change. KfW Entwicklungsbank. (n.d.). Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.kfw-entwicklungsbank.de/International-financing/KfW-Development-Bank/About-us/Corona-in-Financial-Cooperation/Honduras/.

Honduras. WageIndicator subsite collection. (2021). Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://wageindicator.org/salary/minimum-wage/honduras.

Honduras. World Bank. (2021). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/honduras

Institute, G. (2018). Fact sheet abortion in Latin America and the Caribbean. Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/factsheet/ib_aww-latin-america.pdf.

Jokela-Pansini, Maaret. “Complicating Notions of Violence: An Embodied View of Violence against Women in Honduras.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, vol. 38, no. 5, Aug. 2020, pp. 848–865, doi:10.1177/2399654420906833.

Kelly, A. (2011, May 28). Honduran police turn a blind eye to soaring number of ‘femicides’. The Guardian. Retrieved December 20, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/may/29/honduras-blind-eye-femicides

Menjívar, C., & Walsh, S. D. (2017). The Architecture of Feminicide: The State, Inequalities, and Everyday Gender Violence in Honduras. Latin American Research Review, 52(2), 221–240. DOI: http://doi.or/10.25222/larr.73

Murphy, A. (2012, February 12). ‘who rules in Honduras?’ Coup’s legacy of violence. NPR. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www.npr.org/2012/02/12/146758628/who-rules-in-honduras-a-coups-lasting-impact.

ne-MH, teleS. U. R. /. (2018, November 28). UN: ‘machismo’ in Honduras driving epidemic of femicides. News | teleSUR English. Retrieved December 19, 2021, from https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/UN-Machismo-in-Honduras-Driving-Epidemic-of-Femicides-20181128-0017.html

Philipp, J. (2020, September 12). How Honduras uses US foreign aid. The Borgen Project. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://borgenproject.org/honduras-uses-us-foreign-aid/.

Philipp, J., Thelwell, K., & Project, B. (2020, June 25). Poverty in Honduras. The Borgen Project. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://borgenproject.org/tag/poverty-in-honduras/.

Portes, A., & Hoffman, K. (2003). Latin American Class Structures: Their Composition and Change during the Neoliberal Era. Latin American Research Review, 38(1), 41–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1555434

Rachel Lomot. “Gender Discrimination: A Problem Stunting Honduras’ Entire Economy.” Global Majority E-Journal, Vol. 4, No. 1 (June 2013), pp. 15-26. https://www.american.edu/cas/economics/ejournal/upload/lomot_accessible.pdf

The “most dangerous city in the world” – especially for sex workers. Amnesty International USA. (2014, January 18). Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.amnestyusa.org/the-most-dangerous-city-in-the-world-especially-for-sex-workers/.

Tuckman, J. (2014, November 19). Death of miss honduras and sister shocks nation with worst homicide rate. The Guardian. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/19/miss-honduras-murder-sister-boyfriend-arrested-shocks-nation.

Women, U. N. (2000). Beijing +5 – women 2000: Gender Equality, Development and peace for the 21st Century Twenty-third special session of the General Assembly, 5-9 june 2000. United Nations. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/followup/session/presskit/fs1.htm

World Bank Group. (2021, October 7). Poverty and equity briefs. World Bank. Retrieved December 19, 2021, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/publication/poverty-and-equity-briefs

World Report 2021: Rights trends in Honduras. Human Rights Watch. (2021, January 13). Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/honduras.