FRIDAYS FOR FUTURE: YOUTH IN MOVEMENT

With a focus on social movements as tools for citizen participation in global movements, I turn to the Fridays for Future movement. Started by Greta Thunberg in 2018, the movement has garnered worldwide support and has been able to mobilize and target historically underrepresented groups in politics; namely children in politics. Because they are under the legal voting age, it is easy for minors’ voices to be overshadowed by the adults in positions of power in the realm of political movement. Thunberg was able to harness her strength as a figurehead for children in political movement in order to galvanize the world.

SOCIAL MOVEMENTS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

In Manuel Castells’ second volume of his trilogy on globalization, identifies types of identities used in social movements. The first of these is the “resistance identity” as defined by Castells. Castells describes resistance identity as “the most important type of identity-building … against otherwise unbearable oppression, usually on the basis of identities that were, apparently, clearly defined by history, geography, or biology” (Castells 9). However, Castells makes a point to note that the resistance identity alone is not as useful to the social movement but rather the “project identity” is the superior identity for movement making. Castells acknowledges that a project identity may be built “on the basis of an oppressed identity,” but expands that it must push for “the transformation of society” (Castells 10). This confluence of the resistance and project is incredibly salient when looking towards the leaders of social movements.

Furthermore, Castells classifies environmental movements into five types: Conservation of nature, Defense of own space, Counter-culture/deep ecology, Save the planet, and Green Politics (Castells 112). In this framework, Castells separates the types based on their overall goals of wilderness, quality of life/health, ecotopia, sustainability, and counterpower, respectively. Castells argues that environmental movements ought to change the notion of time from “clock time” to “glacial time” which he defines as: “the idea of limiting the use of resources to renewable resources… predicated precisely on the notion that alteration of basic balances in the planet and in the universe, may, over time, undo a delicate ecological equilibrium, with catastrophic consequences.” (Castells 125) This notion of time is used to “propose sustainable development as intergenerational solidarity brings together healthy selfishness and systemic thinking in an evolutionary perspective” in order to redefine the urgency of the environmental crises (Castells 126).

In contrast, Peter Evans puts livelihood and sustainability into conversation and takes a critical approach to Castells’ writings. Evans discusses the ways in which poorer cities must juggle the dichotomy of trying to keep up with technological advances and trying to keep their land clean. Evans characterizes this choice as “ecological degradation [buying] livelihood at the expense of quality of life, with citizens forced to trade green space and breathable air for wages.” (Evans 2) Evans critiques Castells’ work in The Informational City, in which Castells claims ordinary people are excluded from wielding power at most levels. Evans, however, finds this claim to be hasty and says “the possibility of ‘green growth machines’ or even ‘urban livability machines’ cannot be ruled out.” (Evans 13) Evans advocates for the use of Non Governmental Organizations (NGOs) or political parties to act as “translocal intermediaries,” harnessing the ideas and advocating for the needs of the everyday person.

Similarly, Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink advocate for the creation of larger advocacy networks in order to broaden the political opportunity structure of a given movement. Keck and Sikkink discuss the possibilities of “network activists [seeking] international or foreign venues in which to present claims, effectively transforming the power relationships by shifting the political context.” (Keck and Sikkink 221) By drawing on this larger network of advocates, Keck and Sikkink illustrate the ways in which the power of the ordinary person can be amplified into a fully realized movement, able to put their issues onto the political agenda. Keck and Sikkink however, distinguish between transnational advocacy networks and transnational social movements. The difference they identified was that advocacy networks work is based on information and while it “may involve mobilization; more often it involves lobbying, targeting key elites and feeding useful material to well-placed insiders.” (Keck and Sikkink 236). They acknowledge the large overlap between the two groups, along with their differences, but ultimately they find both to be useful tools of change.

In “How styles of activism influence social participation and democratic deliberation,” Favareto and others, look into the trajectory of leaders of social movements and how these trajectories can predict the overall effectiveness of their movement and their willingness to engage participatory government. They hypothesize that the more “heterogeneous” the socialization of a movement’s leader, the more likely they will be to make more ties that are weaker and create a larger advocacy network, furthering their movement. This was supported by their research about Gabriel Oliveira “whose cultural capital – associated with his personal network of relations in the business and non-governmental organization (NGO) world – [had] been converted into political and economic capital.” (Favareto et al. 253) These findings correlate with Keck and Sikkink’s work regarding the importance of building large advocacy networks.

THE CASE STUDY

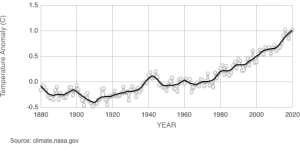

The issue of environmental protections is one that cannot be put off any longer. With sea levels rising over 2 inches, global temperature rising 0.63 °C, and the frequency of high level (category 3-5) hurricanes rising since 2000, it has become abundantly clear that climate change is inevitable and the effect of industrialization, globalism and capitalism have made a lasting mark on the ecological history of the Earth (NASA). While the social movements surrounding climate change are not new, in the scope of social movements, it has been relatively well received. The newest in this list of environmental social movements is the Fridays for Future movement started in 2018 by Swedish teenager, Greta Thunberg.

The movement originates from Thunberg’s own personal actions, in which she would go on strike from her school every Friday in front of the Swedish Parliament. Thunberg, 15 at the time she started striking, quickly rose to prominence as the face of the movement and a serious political figure. Her goal was to demand action from political leaders to take action to prevent climate change and for the fossil fuel industry to transition to renewable energy, a large undertaking for one child alone. However, she was not alone for very long. Once she started to gain attention from news outlets, her movement skyrocketed into a global phenomena. This increase in media attention led to an increase in participation in her movement: in less than a year Thunberg went from protesting alone to being the figurehead for a strike boasting 3.7 million participants in over 150 countries (Fridays for Future). Thunberg was invited to many Climate Change Conferences worldwide, including both the 2018 United Nations Climate Change Conference and 2019 United Nations Climate Action Summit, at which she advocated for the environment and spoke for a younger generation, a historically underrepresented group in the realm of climate change.

While concerns surrounding the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic persist, the Fridays for Future movement has moved to the digital sphere, where it first gained traction. This lull in action has led many to consider whether the Fridays for Future movement was actually able to make any lasting change. Once it picked up traction, it seems Thunberg and the movement set its sight on the United Nations as it’s target. Choosing a trans-national organization is a risky decision for a social movement, as is controlling such a large multi-national movement. With Thunberg at its helm, Fridays for Future has had a seat at the table amongst these giant organizations, but was the movement truly taken seriously on the international stage? Or were the invitations just used to placate a movement centering around young people into submission?

The question of the movement’s actual effectiveness is contested, especially given its relative newness. However, the movement stems from a long history of environmental movements, dating back over 50 years. Drawing on the networks and repertoires of past environmental movements, the Fridays for Future movement has been able to increase the current political awareness of climate change issues. The most remarkable feat of Fridays for Future is its unique draw amongst younger people. People below the voting age of 18 are oftentimes underrepresented in political activism spaces and especially in environmental activism spaces. With a majority of Greenpeace, a comparable global movement, members falling between the ages of 31-45 in 2018, the same year Fridays for Future began, the gap is significant. The Fridays for Futures’ inception was on social media, so naturally, it drew in a younger more technologically savvy group of activists. The immediate accessibility to the movement, which is what caused it to gain almost overnight success, is one of its greatest assets.

Amongst younger populations that have grown up with the impending threat of climate change, it was refreshing to see themselves reflected in the mainstream discussions surrounding climate change and it’s possible solutions. However, to the older generation, the young activists were not seen as credible. This has led to many challenges for the Fridays for Future movement in the framing of both their mission and of the activists themselves. Looking retroactively at the movement during its current downswing, we can gain some insight into whether or not the movement has had any lasting effects. We can also look to the future of the movement and hypothesize about its future capacity to grow and affect change.

ANALYSIS

THE MANY IDENTITIES OF THE MOVEMENT

Thunberg, as the very public face of the movement, has differentiated herself and her movement from others by emphasizing her position as both a minor and neurodivergent. Through this, Thunberg creates a sort of “resistance identity.” Thunberg, being a young girl with Asperger syndrome, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and selective mutism, squarely falls into the category of being oppressed on the basis of these identities. She is able to harness her various identities into a stronger resistance identity against the various national and international systems with which she takes umbrage. Her issues with these systems, namely the governments of what she deems to be “rich countries,” such as her home country of Sweden, are that they are not actively trying to combat climate change despite committing to the Paris Agreement.

A large part of her “resistance identity” is her age. Being a young woman, only fifteen at the time of her TEDx speech, she represents a commonly overlooked faction of the population. People younger than the voting age are often not taken into consideration when it comes to the decision making process. Thunberg actively pushes back against this framework. By activating and mobilizing a largely untapped population, Thunberg was able to corral the support of people her age into her movement and into the worldwide expansion of her message. In her speech, Thunberg directly addresses her critics who base their critique on her age and commonly “say that [Thunberg] should be in school instead [of protesting]” (Thunberg 08:20-08:22). However, Thunberg responds to the adults who criticize her by asking them “why should I be studying for a future that soon will be no more when no one is doing anything whatsoever to save that future?” (Thunberg 08:43-08:52) This push back is in direct contrast to the emphasis the entire institution of education usually places on it’s future value. Thunberg’s use of this apocalyptic rhetoric resonates with young people in her age bracket, successfully putting value on and mobilizing the untapped political potential of young people who disagree with the ways the climate crisis is being handled by adult politicians.

Through her actions, Thunberg is able to translate her “resistance identity” into a “project identity.” Castells acknowledges that a project identity may be built “on the basis of an oppressed identity,” but expands that it must push for “the transformation of society” (Castells 10). In Thunberg’s TEDx talk, her explicit call to action is that “rules have to be changed. Everything needs to change, and it has to start today” (Thunberg, 10:47-10:55). This call for a transformation of society and the rules governing the response to climate change exemplifies the shift in her identity from simply a resistance identity to a project identity, with her project being the changing of the way the climate crisis is viewed and handled by governments. Thunberg radically calls on “rich countries … to get down to zero emissions within 6 to 12 years” in order to allow for poorer countries to “have a chance to heighten their standard of living by building some of the infrastructure that [rich countries] have already built.” (Thunberg 04:44-05:02) The climate justice and equity Thunberg calls for is not new by any means, but to hear it coming from someone so young adds an extra layer of urgency.

LIVABILITY AND SUSTAINABILITY

This call for the richer countries to create space for poorer countries echoes Evans’ aforementioned critique of Castells. Thunberg, possibly unknowingly, harkens back to Evans’ emphasis on the oftentimes exorbitant costs of creating liveability and sustainability in areas that are lacking in funds. By urging the rich countries to focus on sustainability while allowing poorer countries the opportunity to build up their livability standards. While Evans’ original theory focused more on a singular community’s struggles with balancing sustainability and livability, an expanded view of Evans allows the theory to be applied to the global community. In this expanded view of Evans, green “growth machines are also ecologies of agents,” making them an interconnected ecology of agents in a global community of urban livability. In an interview with The New York Times, Thunberg touched on this topic again, saying “we forget that the majority of the world’s population don’t have that opportunity and won’t be able to adapt. They’re also the ones who are going to be hit hardest and first and are least responsible. That is being ignored to a degree that is pathetic” (Marchese 2). Her focus on richer countries’ impact while still centering the disastrous effects this will have on poorer nations distinguishes her from other activists.

BROADENING THE POLITICAL OPPORTUNITY STRUCTURE

While Thunberg’s organizing is certainly original in its global scope, it draws on previous movements and the work done to make those movements successful. Following Keck and Sikkink’s framework of transnational advocacy networks, the Fridays for Future movement “sought international or foreign venues in which to present claims, effectively transforming the power relationships involved by shifting the political context” (Keck and Sikkink 221). By presenting her claims at the United Nations Climate Action Summit in 2019, and being the only minor to do so, Thunberg was able to expand her reach. Before Thunberg, very few minors were able to have their voices heard and listened to in the political arena. Thunberg cites one of the few movements headed by minors, the March For Our Lives, started in early 2018, as an inspiration. In an interview with CNN, Thunberg stated that she had heard about March For Our Lives and wondered “what if children did that, but for the climate?” (CNN 1:30-1:45) The March For Our Lives movement, a gun control movement started by survivors of the fatal shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, was able to reach a national audience and was able to enact change at both the state and federal level. March For Our Lives used political tactics such as lobbying, social media campaigns, and marching as the name suggests, but Thunbergs inspiration came from the organized school walk-outs carried out by the movement. By taking the existing structure of the school walk-outs and shifting that strategy into a transnational advocacy network, Thunberg was able to expand the political opportunity structure for children looking to get involved in social movements.

NETWORKS OF SUPPORT

In her many meetings and appearances amongst the leaders of the world, Thunberg has created a vast network of allies. Thunberg’s socialization patterns would be categorized by Favreto and others as heterogeneous because of the large amounts of weaker ties she has to a wide range of people. In the media, Thunberg has been the subject of profiles in The New York Times, interviews with CNN, and many other major news outlets internationally such as the BBC. In pop culture, Thunberg has garnered support from the likes of Jane Fonda, Mark Ruffalo, and Billie Eilish amongst dozens of other celebrities who participated in boosting the movement on social media. In politics, Thunberg has been invited to speak at the United Nations Climate Action Summit in 2019 and has had meetings with world leaders like Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron. By creating this large number of weaker ties, Thunberg has created an abundance of “weak ties, infused with a certain degree of plurality, [which] tends to conform to styles of activism that are more open to dialogue and negotiation with different groups” (Favareto et al. 249). By keeping so many channels of dialogue open in many sectors important to the public eye such as media, celebrity, and politics, Thunberg has created an incredibly strong network of support for her movement to succeed in.

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD FOR FRIDAYS FOR FUTURE?

Amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic, social movements have had to shift their focus. Originally, Fridays for Future’s main actions were in-person marches and rallies drawing in enormous crowds. With social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and slow vaccine roll outs, the movement has focused more on their social media presence and education regarding climate change. While Fridays for Future is not the only movement having to navigate the pandemic, it was uniquely poised for the transition to an online movement given its young membership. According to Pleyers, “national and international movement networks are actively engaging in sharing experience and analyses via online platforms and social media… [which] have been set up for grassroots movements from different continents to share experiences and analyses” (Pleyers 303). The pandemic has also highlighted the intersectionality of multiple social movements where the “the crisis reveals the deep social, political and ecological crises we face” (Pleyers 303). The pattern over the last year has shown that, similar to other illnesses, COVID-19 cases surge in the winter months and with it snowing as late as mid-April in parts of New England, the effect of climate change is far reaching. This current moment sees a downturn in the Fridays for Future movement, with less participation than seen before.

Looking to the future of the movement, however, is bright. The climate justice and equity Thunberg calls for is not new by any means, but to hear it coming from someone so young adds an extra layer of urgency. If the children of the world have taken notice of how pressing the issue of climate change is and have taken into account the ways to fix it equitably, why haven’t the politicians? This question lies at the heart of Thunberg’s activism and therefore at the heart of the Fridays for Future movement as a whole. Children internationally are calling for an overhaul in the rules used to govern and mitigate the effects of climate change. It is refreshing to see a movement built by and for young people gain such incredible traction. This movement’s most revolutionary potential is it’s room for growth and refinement as those involved age with it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Castells, Manuel. 2010 [1997]. Preface: xv-xviii; Introduction and Chapter 1: “Communal Heavens: Identity and Meaning in

the Network Society,” pp. 1-45; 54-70 in The Information Age. Economy, Society, and Culture. Volume 2: The Power of Identity. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing (2nd edition)

CNN “Teen activist on climate change: If we don’t do anything right now, we’re screwed.” Youtube, uploaded by CNN, 23

December 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGmBkIUwYkA

Evans, Peter. 2002. “Looking for Agents of Urban Livability in a Globalized Political Economy,” pp. 1-23, in Peter Evans (ed.)

Livable Cities? Berkeley: UC Press

Favareto, Arilson; Carolina Galvanese; Frederico Menino; V era Schatten Coelho; and Y umi Kawamura. 2010. “How styles of

activism influence social participation and democratic deliberation” pp. 243-263 in Vera Schatten Coelho, and Bettina von Liers (editors). Mobilizing for Democracy: Citizen Action and the Politics of Public Participation. New York: Zed Books

Fridays for Future. “Strike Statistics – Countries.” Fridays for Future, 2021,

https://fridaysforfuture.org/what-we-do/strike-statistics/list-of-countries/. Accessed 7 5 2021.

Geoffrey Pleyers (2020) The Pandemic is a battlefield. Social movements in the COVID-19 lockdown, Journal of Civil

Society, 16:4, 295-312, DOI: 10.1080/17448689.2020.1794398

Greenpeace. “Greenpeace International Annual Report 2018.” Greenpeace International Annual Report 2018, 2019,

https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-international-stateless/2020/01/308756b8-greenpeace-international-annual-report-2018.pdf. Accessed 7 5 2021.

Keck, Margaret and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “Transnational Networks in the Movement Society,” pp. 217-238 in David Meyer

and Sidney Tarrow (eds.). The Social Movement Society. New York: Rowan & Littlefield

Marchese, David. “Greta Thunberg Hears Your Excuses. She Is Not Impressed.” The New York Times, 30 October 2020,

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/11/02/magazine/greta-thunberg-interview.html.

Thunberg, Greta “School strike for climate – save the world by changing the rules | Greta Thunberg | TEDxStockholm.”

YouTube, uploaded by TEDx Talks, 12 December 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EAmmUIEsN9A&t=659s

NASA. “Global Temperature.” NASA Global Climate Change, 2021,

https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/. Accessed 7 5 2021.