9 Unequal Systems of Reinforcement

Institutional Discrimination

The divergent and unfair treatment that students of color receive in American schools limits their opportunity and perceived ability to ultimately reach their professional potential. As agents of early socialization, interaction, and validation for young children, schools play a critical role in developing young people’s identities and self-esteem. However, from the beginning, students of racial minorities receive divergent treatment and differing responses to their behavior, which places them at an inherent disadvantage. Students that “look different” receive different responses for acting like other children, as misbehavior becomes “aggression” (Adichie, 212). This treatment of young students of color is not only unfair. It harms their confidence and misconstrues their ideas of justice, as they experience incomparable discipline for comparable behavior. In addition, many white teachers make comments toward students of color that discourage them from pursuing admirable professions, like doctors or lawyers (Adichie, 212). This mistreatment of students’ future hopes harms the elements of their identity that regard their contributions to the world. It deters them from viewing themselves as valuable members of society and places them at a disadvantage versus their white peers, who are continually empowered by role models in the form of teachers, subjects of study in school, or much of the media.

Unjust, negative encounters with figures of authority can cause trust issues and damage children of color’s self-esteem. And the institutional effects of these encounters can strip children of the positive role models they need. Studies have found that “Black and Latino youth, particularly males, are most likely to report negative encounters with adults in the educational system, shopkeepers who accuse them of stealing, and negative interactions with the police” (Sanders-Phillips et al, 178). As young people mature and develop an understanding of the world around them, such unfair interactions can scar their perspectives of both themselves and others at a critical time of identity development. These negative public interactions can lead to paranoia, trust issues, and emotional troubles. But they can also have broader, institutional effects, such as the development of informal rules regarding public behavior, particularly violence, known as a “code of the street” (Anderson, 33). As this “code” provokes public violence or, at times, illegal activity, it has, along with the war on drugs, contributed to the issue that “more African American adults are under correctional control today – in prison or jail, on probation or parole – than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began” (Alexander, 224).

For young, black men, many of whom crave role models to set personal goals and establish self-worth, the effects of this institutional discrimination can take a psychological toll, as proven in Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing. As H, a recently freed slave, accustoms himself to a new mine where he will work, he begins to wonder “if there was a black man left in the South who hadn’t been put in prison” (Gyasi, 173). As a black man, himself, H’s observation of so many black men in prison may cause him to see himself as someone who belongs in prison, similarly to how millions of American children of color “grow up believing that they, too, will go to jail” (Alexander). Given that prisons are systems of correction for people in need of detainment and discipline, H may begin to incorrectly feel that he does not deserve to be a free man or is too poorly behaved for the free world, which can surely hinder his confidence, similarly to students of color who hear from teachers that they are “not smart enough to be doctors” (Adichie, 405). This mistreatment can instill a condition of anomie in young people of color, which consists of hopelessness and perceptions of little control over life outcomes. The anomie “develops when children perceive contradictions between opportunities in the larger society and the conditions and lack of opportunity in their own lives” (Sanders-Phillips et al, 178).

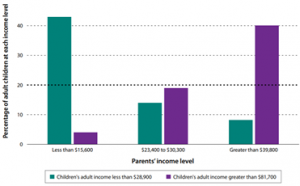

In both direct and indirect manners, children of color have been denied the opportunity for economic success and social progress. The United States has a history of unparalleled race-based slavery and racism, much of which is still prevalent today. In James Coser’s Sociology through Literature, a young Richard Wright starts his first job in an office among older, white men. He is determined to succeed and improve. But when he asks for help and training, the men react in shock and maliciously ask if he thinks he will “ever amount to anything” (Coser, 306). In doing so, these men both harm Wright’s early dreams of professional success and directly scare him away from his first, hard-earned job. Similarly, in Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, Robert is a light-skinned man who initially has few barriers to employment. But once employers discover that he is married to Willie, a black woman, they immediately fire him (Gyasi, 207). This decision represents the absurdity of the racism of America’s economy and job market, but also the white corporate sector’s efforts to contain the economic success of African Americans. Willie later illustrates this phenomenon more directly by observing that a wealthy, black family could only move “as close to the white folks as the city would allow” (Gyasi, 209). These restrictions on black families and their children deny many children of color access to professional success and social mobility through a lack of access to the same geographic and community resources as white families. As a result, black children in the lowest income quintile are nearly twice as likely as their white counterparts to remain in the lowest quintile as adults (Figure A).

Figure A. More Black Downward Mobility

White Children’s Conditional Transition Probabilities

Black Children’s Conditional Transition Probabilities

Source: Pulliam

A Comparative Disadvantage

As American income inequality grows, its effects increasingly place lower-class families and children at a disadvantage. In 2011, 29% of American families earned less than enough to cover childcare among other essentials, (Ehrenreich) which means that 29% of American children grew up without access to the necessary care and resources that are abundant for upper-class children. And in the past twelve months, the economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic have exacerbated this disparity. Amid the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression, a “subset of companies is experiencing dramatic, windfall profits,” (Oxfam America, 1) as 17 of the 25 most profitable US corporations are expected to make almost $85 billion more in 2020 super-profits compared to previous years (ibid, 1). The top 10% of Americans control over 88% of these profits, while the bottom 50% has earned “next to nothing” (ibid., 7). This uneven economic development demonstrates how American class disparities are growing. American children’s access to wealth and opportunity is becoming increasingly unequal.

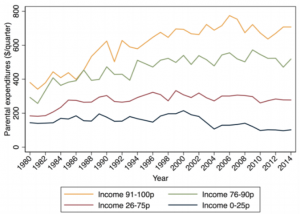

Low-income parents with less profitable and more time-consuming jobs cannot provide their children with the same resources as upper-class children, which hinders lower-income children’s cognitive development and academic performance. In doing so, it strips them of future opportunities. Research has found that parents in the top decile of earners spent five times what parents at the median household income spent on children from 2006 to 2007 – $11,000 compared to $2,220 (Figure 2) – but also that parental time investments in children are strongly patterned by economic class (Schneider et al). These data prove the myriad of ways in which upper-class parents invest in their children, which low-income parents cannot perform. For low-income children, this lack of investment may not only create a comparative disadvantage but also hinder their self-confidence or paternal relationships. They may witness other, wealthy parents dedicating time and capital toward children that their own parents cannot afford to do. The ‘more involved’ parenting that upper-class children seem to receive, which entails parents providing educational materials, enrolling students in activities, and spending time with children, is positively related to children’s test scores and cognitive development” (Schneider et al, 476). This relationship proves the effect of the developmental investment that upper-class children receive but also the comparative lack of benefits with which lower-class children must develop. It further reinforces the concept of immovable castes. Wealthy children with higher test scores pursue more education and earn jobs comparable to those of their upper-class parents, while “a child born to parents with income in the lowest quintile is more than ten times more likely to end up in the lowest quintile than the highest as an adult” (Greenstone et al, 6).

Figure 2. Parental Financial Investments in Children per Quarter by Household Income

Percentile Rank

Source: Schneider et al, 477

Figure 3. Probability of Children’s Income Level, Given Parents’ Income Level

Source: Greenstone et al, 6