3 Case Study— Trauma, Anger, Socialization, and Political Consciousness in Revolutionary Suicide

Applying the idea of political consciousness as a continuous process rather than a fixed condition to Huey P. Newton’s autobiography, Revolutionary Suicide, allows us to better understand how racialized socialization interfaces with the lives and experiences of people of color. As such, we can use Revolutionary Suicide as a vehicle to better understand the complexities of trauma, anger, and consciousness within broader society. This section focuses specifically on the early chapters of Newton’s autobiography, because this is where we most clearly see the detrimental, traumatizing impacts of racialized socialization on children, as well as Huey Newton’s own journey towards revolutionary consciousness. Though this extends far beyond the bounds of the classroom, the specific contexts of education provide a particularly compelling window into the realities of socialization, and more importantly, how this socialization continues to impact its victims long into adulthood.

In Chapter 6, we can see the varied, pervasive ways in which rules and disciplinary guidelines were (and still are, today) weaponized against students of color, specifically Black and Indigenous students. For instance, after being sent to the principal’s office for a minor offence, Newton was only allowed to return to class for the remainder of the semester on the grounds that he said nothing in class, ever. While very little time needs to be spent explaining how antithetical this is to the spirit of teaching, he nonetheless agreed to this rule, and spent his time in class doing and saying nothing, out of fear of breaking the rules. One day, however, he forgot, and raised his hand to ask a question, which resulted in him being reprimanded. Newton argued that it was impossible to learn without asking questions, and then left the classroom. He was kicked out of that high school not long after. (81)

This was not a unique incident. In elementary and middle school especially, repeated patterns of harassment and alienation are clearly displayed by Newton’s teachers. Whether it’s a teacher striking him across the face with a book because he took too long getting off the playground, or purposefully humiliating him in front of the class to the point where he couldn’t spell simple words in front of others, the public education system proved to be a very detrimental system to Newton and countless children like him. (48-49; 111) This was done in an attempt to bully and intimidate him out of the school system, and Newton was certainly not the only child who faced this sort of abuse. While data surrounding the scope of children of color affected by racist harassment in schools is hard to come by, much has been written on how this impacts perceptions of self and mental health. As we see in a study conducted by the American Academy of Pediatrics, children tend to live up—or oftentimes in the case of children of color, live down—to the expectations set by teachers. (Ginsburg and McClain 318) The tragic reality is, if teachers weaponize the classroom in oppressive attempts to intimidate students, most of the time, it will work, which has devastating impacts throughout the rest of the child’s life. This is because at a young age especially, these categories of characterization and stereotype are detrimental to perceptions of self. It is the reason why Marx, in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, famously said “[i]t is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.” (21) People are not only products of their environments, but the very conditions from which they were socialized from also determine how they understand themselves and the world around them. This concept informs the idea of the color line acting as a damaging, obscuring agent, (Du Bois 13-39) and is therefore a key component of understanding harassment and humiliation within racialized socialization.

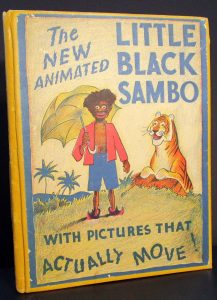

Specially-tailored surveys conducted by Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research reveal not only the political and social disparities generated by racism, but also the damaging effect it has on health and perceptions of self. (Garcia et al. 349-373) While this is valuable insight on its own, this can be combined with the fact that children of color—or more specifically, African-American children—are socialized into certain awarenesses of race, the result of both harassment from living in racially hostile environments, as well as familially-taught warnings and lessons about the dangers of existing within such a society. Moreover, instances of adolescents reacting with either anger and depression from such treatment tend to bring about silencing and misdiagnosis, which can turn into even more precarious or damaging situations still. (Stevenson et al. 197-222) In other words, people of color do not need to read a book to know what race or racism is— the seed of awareness and understanding is planted by the simple fabric of everyday life and the oppressive dehumanization of socialization. These understandings, even those imparted for the safety of aforementioned children, are nonetheless harmful to their own mental health. This is shown clearly in chapter 2, where we see the example of the story “Little Black Sambo”, an incredibly racist children’s book. The cover alone is telling enough, and is pictured below.

“Little Black Sambo”, a picture book taught within the curriculum Newton experienced during his time as an elementary schooler.

Huey Newton describes the effect it had on him even as a kid, saying that the Black students in the class “accept[ed] Sambo as a symbol of what Blackness was all about.” (47). Both Stevenson and Newton’s works point to the same conclusion— that these awarenesses of race are both instilled in children of color at an incredibly early age, and that the understanding of themselves as a racialized being is already harmful in and of itself. Du Bois’ “double consciousness” and racial subjectivity is at play here, and reinforces the vision of racism as a disruptor and damaging agent within social interactions. (Du Bois 3-5) Specifically, the injurious effects this awareness has on children is an example of double consciousness. In this sense, children of color are forced into not only seeing themselves as a child, a student, a human being; but also as a racialized category, a stereotype, a target for cruelty and harassment. We can understand the color line, then, as something that does more than just divide communities and public spaces; it creates a divide within perceptions of self, too. But where the color line traumatizes and alienates, the sociological imagination provides chances at clarity and resistance.

People of color may not need books, formal education, or theoretical frameworks to know what racism is, but that does not make the sociological imagination obsolete. This knowledge acts not as a shining light upon which people get to see their struggles for the first time, but instead a framework that helps them understand and contextualize the larger picture. Though this has been written about extensively (Coontz, Cooper, Haddad and Lieberman to name a few), and something mentioned in the introduction and thesis, Newton yet again provides a striking example of this, in Chapter 3 of Revolutionary Suicide. He describes the frequent fights that broke out between him and other classmates and friends alike growing up, before retrospectively reflecting on it, saying: “I was too young to realize that we were really trying to affirm our masculinity and dignity, and using force in reaction to the social pressures exerted against us. For a proud and dignified people fighting was one way to resist dehumanization. You learn a lot about yourself when you fight.” (52) At the time, Newton didn’t think of or identify the specific structures that made him feel the way he did— his awareness was one rooted in emotions such as frustration, and he reacted accordingly. It was through the sociological imagination that he could then look back on his life, and understand these feelings and troubles within the larger contexts of white supremacy and capitalism in America. Moreover, these lessons he learned in fighting and defiance were mirrored in the ideological development of himself and the Black Panther Party. These ideas of resistance, pride, and violence as a defensive response are among the key tenets of the Party, from its very inception. (161-163) What this means, then, is that this relationship between lived experience and the sociological imagination is a two-way street. Just as the sociological imagination provides the opportunity for marginalized groups to format and critique the oppression they face, that same lived experience then goes on to inform this viewpoint further. These accomplishments happened in spite of, and because of, the marginalization revolutionaries faced. As such, we can understand their paths to revolutionary consciousness as recurring processes of synthesis, and by extension, healing.