24 Analysis: The Two D’s: Docility and Dominance

As demonstrated by Martin, Boswell and Spade, and Messner, patriarchal societies emit a sexist idea that women should by nature be submissive to men. For example, the entire role of women within The Handmaid’s Tale is to complete all the housework and act as vessels for future children under the dominion of men. A woman goes so far as to claim that the epitome of female freedom is for all women to live in unity and conduct all household chores (Atwood 163). These dynamics portray an exaggerated version of women being condemned to traditional roles of housekeepers, while men are depicted as the authoritative breadwinners. As asserted by Martin, traditional forms of masculinity are assertive, whereas those of women are seen as passive and serviceable (504). Essentially, the novel’s portrayal of women as homemakers accentuates the power imbalance through a master-servant-like dynamic.

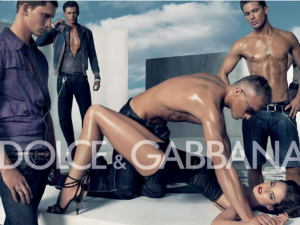

These depictions of female docility and male dominance are not just limited to literature. Kilbourne’s study on the sexualization of women and men through advertisements shows that female poses are dainty and fragile, while men are positioned to look bigger and stronger. Orenstein’s “The Miseducation of the American Boy” demonstrated that young men value dominance, aggression, sexual prowess, stoicism, and athleticism. As shown by Messner, the correlation between masculinity and athleticism is a result of sports providing an outlet for men to exercise strong violent movements. Additionally, the emphasis on sexual prowess is built on the idea of male domination over women, as seen with Boswell and Spade’s study on collegiate fraternities. Similarly, the formation of “jock culture” within male-dominated circles is a result of group solidarity being established through weaponized misogynistic remarks that assert the dominance of manhood. The following Dolce & Gabbana ad reinforces these archetypes of female submissiveness and male aggressiveness.

Such ads reinforce the idea that women are “passive partners” and men are “initiators of sex” (Boswell and Spade 138). Furthermore, the prominence of female bondage imagery is due to advertisements capitalizing off exaggerated models of femininity and masculinity. At a young age, girls are taught to be cognizant of their bodily manners and spatial positioning (Martin 502). To portray fragility, women are positioned in awkward positions that emit frailty. In comparison, male positions extrude dominance and strength. When juxtaposed together, the ads depict males as overpowering women to reinforce bodily expressions of femininity and masculinity.

Both Park and Coontz determined that male emotional vulnerability is not particularly valued in men as it serves to emasculate them. Since men are encouraged to go into competitive environments, vulnerability is perceived as a weakness and creates a toxic masculine culture. It is for this reason that 40% of young men in Orenstein’s article felt compelled to act combatively when angry. Young men are never taught to be emotionally expressive as it is perceived to be a feminine trait. By default, masculinity is associated with apathy as it helps reassert notions of superiority since emotions are equated to weakness.

Atwood’s portrayal of female treatment in The Handmaid’s Tale, Kilbourne’s and APA’s study of sexualization in media, and Orenstein’s study on masculinity all demonstrate that women and men are both generalized and objectified in manners conforming to traditional perspectives on femininity and masculinity.