3 Case Study: Cultural Transmission of Rape Culture

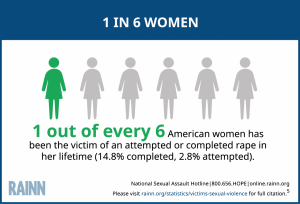

Sexual violence is endemic to our culture. According to RAINN, the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization, 1 out of every 6 American women has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime (14.8% completed, 2.8% attempted). Young women are victimized at the highest rates with women aged 16-19 being 4 times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault. 21% of TGQN (transgender, genderqueer, nonconforming) college students have been sexually assaulted, compared to 18% of non-TGQN females, and 4% of non-TGQN males (RAINN). Indigenous people are twice as likely to experience a rape/sexual assault compared to all races (RAINN), and according to the CDC’S 2010 National Intimate Partner Survey lifetime prevalence of rape for adult women was significantly higher for Black women (22%) than white women (18.8%). About 85 to 90 percent of sexual assaults reported by college women are perpetrated by someone known to the victim; about half occur on a date (National Institute of Justice) and 93% of juvenile victims knew the perpetrator (RAINN). This trend continues beyond sexual assault to fatal violence; of the women murdered in 2007, 64% were killed by a family member or intimate partner (Dept of Justice). The stakes and the need for intersectionality could not be any clearer– sexualized violence is ubiquitous in our society and particularly harming Indigenous & Black women, and trans and gender-nonconforming people.

Investigations like Gatwoods are necessary because we must understand how rape culture functions in order to dismantle it. Rape culture has been documented in countless sociological texts from every angle imaginable; from causes, to effects to the particular nuances of its form within a specific context. For example in “Fraternities and Collegiate Rape Culture: Why are Some Fraternal Organizations More Dangerous Places for Women?”, Ayres Boswell and Joan Z. Spade document how college students behavior in relation to sexual violence changes as people move from setting to setting. They look at fraternity houses with “high risk” and “low risk” rankings for probability of rape and sexual violence and they found that many of the people from both types of frats attend parties in both spaces, but act drastically different depending on the setting. Their findings suggest that “rape cannot be seen only as an isolated act and blamed on individual behaviors and proclivities, whether it be alcohol consumption or attitudes. We also must consider characteristics of the settings that promote the behaviors that reinforce a rape culture. … Peer pressure and situational norms influenced women as well as men” (Boswell & Spade 1996:251). While this source is not explicitly about media consumption, it highlights the way that our environmental context dramatically informs both, how enabled perpetrators feel in enacting violence, and how much potential victims are taught to internalize fear.

Furthermore, in “Campus Safety: Cultivating Spatial Avoidance, Social Dependence and Feminist Resistance,” criminologist Sara M. Walsh writes that the fact that in a previous study personal victimization was not found to be a significant predictor for fear of any singular offense, while indirect victimization (friend or family) was significant implies that “fear is to some extent dependant on cultural transmission, not simply personal experience” and that a more appropriate definition of fear of crime consists of both “risk perception and the emotion of fear” (Walsh 2012:17-18). This idea of fear as a cultural transmission allows us to analyze the way rape culture is perpetuated, not only via the individuals who commit sexual violence, but also through the mechanisms which transmit the fear of violence. We can understand these mechanisms through the lens of symbolic interactionism– through interactions we develop understandings of ourselves in relationship to sexualized violence which then affect how we interpret and act in the world. If one is constantly being told to be vigilant against sexual violence because the people around them perceive them to be a potential victim, one can become incredibly afraid in contexts where others feel completely fine (think of how women often put their keys in between their fingers before walking to their car but men walk from the building to their ride without even thinking about it). It is important to stress that for many, this fear is created and validated by personal experiences of trauma; it is not just cultural institutions teaching women (and folks of other marginalized genders) to fear sexual violence, it is grounded in the reality that 1 in 5 women have been raped, and almost all have experienced some form of sexual harassment or assault in their lifetime. However, I would argue it is still important that we interrogate the societal mechanisms which transmit fear of sexual violence because 1.) living under constant fear is a central component of those marginalized by rape culture and 2.) It allows us to critically analyze who is taught to fear who; who is allowed the room in our society to be afraid and why.

With this in mind, we can turn to the literature which specifically analyzes how crime tv is not only a reflection of our cultural fear and obsession with sexualized violence, it also acts as a mechanism to transmit fear of such. In “The Cultivation of Fear of Sexual Violence in Women: Processes and Moderators of the Relationship Between Television and Fear” Kathleen Custers and Jan Van den Bulck analyze just that– how a random sample of Flemish women fear sexualized violence in relationship to their television viewing. They document how the prevalence of portrayals of sexual violence against women on television has increased significantly in recent decades and how,, “rape has become an acceptable conflict for plot development in dramatic programs” (Brinson qtd in Custers & Bulck 2013:97). They note that this is important because “a culture of fear among women grows among a culture of violence against women” (Yodanis qtd in Custers & Bulck 2013:98). Furthermore, structural equation modeling from their random sample of 546 Flemish women supported a model in which crime drama viewing predicted higher perceived risk of sexualized violence, with especially high rates among those who had not themselves experienced such. This is consistent with the empirical studies that have been done to test cultivation theory across contexts, which have repeatedly found that exposure to television alone is positively related to anxiety about crime (e.g. Chiricos, Eschholz, and Gertz 1997; Eschholz, Chiricos, and Gertz 2003; Chiricos et al. 2000, qtd in Shi, Roche, and McKenna 2019). However, in the 2018 study “Media consumption and crime trend perceptions: a longitudinal analysis,” Luzi Shi, Sean Patrick Roche, and Ryan M. McKenna tested the cultivation hypothesis with three waves of the 2008–2009 American National Election Survey, finding that “it is likely that the cultivation effect of media has been overstated in the previous cross-sectional research” (Shi, Roche, and McKenna 2019). While there is undeniably a correlation between increased crime media viewing and heightened perception of risk of victimization, the authors argue that “it is likely that unobservable variables drew certain users to certain sources of media and simultaneously shape their views on crime” (Shi, Roche, and McKenna 2019). This aligns with the way Gatwood describes her own relationship to crime media– she is drawn to it because of how it serves as a form of catharsis for the violence she has experienced, while being further scared by it.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the media creating (or at least correlating) with this fear disproportionately portrays white women as victims while ignoring Black women and women of color. The 2020 Color of Change report “Normalizing Injustice” analyzed 353 episodes from 26 different scripted series focused on crime and found that “viewers were least likely to see victims of crimes portrayed as women of color, and Black women were rarely portrayed as victims: 9% of all crimes, and 6% of primary crimes” (Color of Change 2020:32). Women of color were depicted as victims less than half the time as white women, despite the fact that they experience significantly higher real-life victimization rates (18.8% of white women, 22% of Black women, and 34% of Indigenous women will experience rape). They also usually portray the police as saviors to women experiencing sexualized violence, even though abuse is roughly 15 times more pervasive within police families than in the general population and police murder Black women all too often (Burmon 2021). Furthermore, these shows depict crime as occurring from a random stranger at a rate which is disproportionate from real life where the majority of people are victimized by people they are already in relationship with. Thus, the cultural landscape media particularly instills fear of violence from strangers in white women like Gatwood, a fact which she wrestles with throughout Life of the Party.

This video describes “Missing White Women Syndrome,” a term coined to describe how cases in which white women murder victims get the most media attention and how this phenomenon creates harm.