9 Analyzing Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee

Multiplicities of Self and the Negotiation of Personhood

Cha introduces Dictee through a sequence of western canonical figures while interjecting letters of homeland as a means of interweaving convergent histories (Cha 1950: 11). Through Cha’s use of letters as both a literary and aesthetic strategy, Cha positions the revisitation of memory through past recollections as integratively constructed with western mythos. As a subject bearing the repercussive histories of a post-colonial Japanese education, French schooling, and an immigrant in America, Cha employs Korean, Japanese, French, and English language systems as a hybrid form of communicating her pedagogical experiences and split linguistic suppression (Cha 1950: 13). Analysis surrounding Cha’s work conversely compares the similarities between Dictee as dictation, more so her use of multiple languages that can otherwise be considered “split” or “fragmented” as a means of creating a form of third space (In Alarcón 1994, et. al 1994: 42).

Dictation can be seen as an expression of authority, an exercise in enforcing power in systems of education. Cha mobilizes language as a means of rethinking through forms of pedagogical power expressed through notions of verbalized knowing. Schooling, being a critical force in nation-state control, has been an institution of power aimed at “dictating subjects in the colonial language, culture, and hierarchy” (Cha 1950: 41; In Alarcón 1994, et. al 1994: 93). The grammatical commands and demands of “correct” pronunciation enforce a sense of linguistic suppression Cha highlights in her work. However, Cha’s interrogation of those instructions by seemingly weaving multiple languages into one creates this sense of illegibility towards authority powers, while simultaneously creating an intermediary where the entirety of her experiences is expressed.

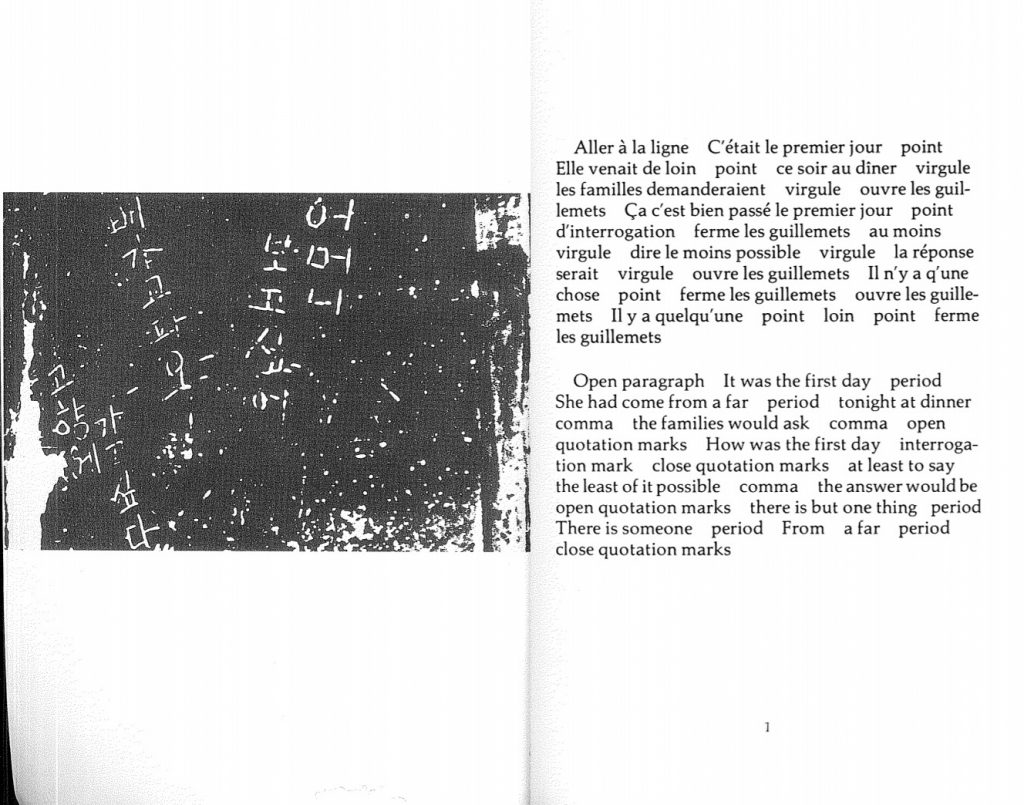

Figure One: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: iii, 1)

Figure One: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: iii, 1)

left image (page iii) is a screenprint engraving overlaid with family photos, presumably her mother, with the text translating to “mother I am hungry;” right image (page 1) is of a French/English translation of the hyper-punctual opening commands Cha is prefacing her text with

To use French, English, and Japanese can be seen as a literary strategy to communicate particular histories rooted in such language structures, but more so, embed stories and memories across the legibility and illegibility of each linguistic character system. Amidst the cacophony of multilingual conversations, there is a sense of invisibility or silence that permits the possibility of a third space Cha is aiming to create – Cha is making her space known.

Figure Two: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 44, 45)

Figure Two: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 44, 45)

left image (page 44) is a photo of her mother at the age of eighteen; image on the right (page 45) is a letter Cha wrote in response to the memory of her deceased mother. The collective pairing of these two pages expresses the return of memory Cha is recalling as she seeks to reconcile with the loss of familial comfort

The literary and aesthetic strategies used in Cha’s work hold striking correspondences to Simmel’s notion of The Stranger. Cha, as “a colonial and post-colonial subject, a religious subject, and as a woman,” brings forth the multiple positionalities in which she occupies and merges those elements together in Dictee. Similar to how Simmel’s notion of the “potential wanderer” is existent in the intermediary space of divergent places, Cha’s positionality is such that places herself within the tensions of “nearness and remoteness” (Cha 1950: 43-47; Simmel 1950: 402).

Parallel to the lived experiences of Korean military brides, these women navigate life in the US as post-war subjects existent between the intermediary tensions of divergent spaces. Given both cultural and legislative pressures to remove what the South Korean government deemed as “expendable bodies” during the Korean War, Camptown prostitutes saw marriage with GI soldiers as opportunities to leave a nation-state where their identities were met with hostility (Cho 2008: 76; Yuh 2002: 119). Upon arriving in the US, many of these women experienced an active erasure of their Korean identities by their husbands and community at large in an attempt to “Americanize” foreign bodies (Takagi 1995: NA). Such disciplinary measures included the schooling of Korean military brides to learn the English language, erasure of Korean cultural practices within home spaces, and the isolation of these women as one of the few Korean women, let alone Asian women, in the early stages of living in US military towns (Takagi 1995: NA; Yuh 2002: 56). Coupled with the recent history of Japanese colonialism and US militarization, many of these women were capable of speaking three languages, Korean, Japanese, and English, as a result of such geopolitical traumas (Yuh 2002: 57). As both “near” and “far away” from their identities as Korean and individuals living in the US, Korean military brides occupy the multiple positionalities as a Korean woman married to an American soldier, an Asian woman living in the US, and a woman whose identities exist both within and outside the fathomability of prescribed classifications. Cha’s linguistic strategy of interjecting multiple language systems captures the negotiation the stranger undergoes when interrogating questions of origin. The “nearness and remoteness” the stranger navigates captures both the spatial/temporal movement of Cha’s work. Her use of cross-linguistic and allegorical imagery problematizes nations of home, origin, and identity as fixated on a singular nation-state. The stranger as “no owner of soil” characterizes the liminality in which Cha occupies and evokes questions of belonging (Cha 1950: 84; Simmel 1950: 402; In Alarcón 1994, et. al 1994: 33).

As this converses with the lived experiences of the Korean diaspora, Cha’s characterization of the multiplicities of self and Simmel’s conceptualization of the stranger help further understandings of Korean military brides post 1950s. Given the impact militarized prostitution has had in 1950s-1960s Korea, many of the women coerced into this system have faced ostracization from their own communities in Korea and saw marriage as a means of potential migration away from intense scrutiny (Takagi 1995: NA; Cho 2008: 187). However, many of these women faced hardships navigating white America and have had to reconcile with the discrimination of being an Asian woman. As defined by Itzigsohn’s explanation of “ethnoracial stratification,” immigrant mobility many of these women faced were restricted in socioeconomic spaces to being part of a “racialized class system” (Yuh 2002: 61; Takagi 1995: NA; Itzigsohn 2009: 45). Such newfound positionality of being part of a racialized minority in the US became an added identity Korean military brides had to navigate.

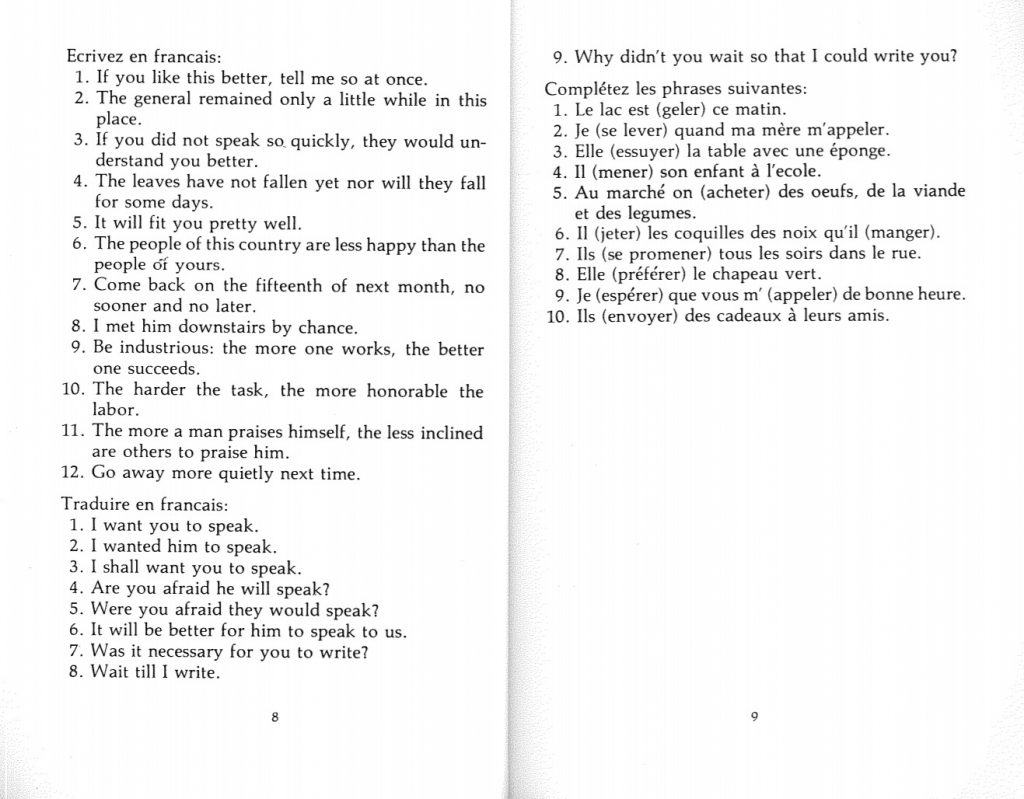

Figure Three: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 8, 9)

Figure Three: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 8, 9)

left and right images (pages 8, 9)“Ecrivez en francais” translates to “write in French, “Traduire en francais” translates to “translate in French,” and “Complétez les phrases suivantes” translates to “complete the following phrases.” Cha blurs between the usage of English and French while utilizing the format of an instructional command that is structurally reminiscent of educational discipline. Depending on the audience, the legibility of both pages becomes rendered to the schooling one receives synonymous with Cha’s

Prior to immigration, many of these women were taught through re-education programs on how to be “good American housewives” for their husbands (Yuh 2002: 233; Takagi 1995: NA). Such practice not only coincides with Cha’s understanding of schooling as a state apparatus for pedagogical control but reveals the practices enforced by both the Korean and United State governments to erase the origins of their identity. Navigating across the margins of legibility and the borders in which they permeate, Korean military brides negotiate the intermediary between two spaces and question the legibility of their origin – the stranger is an embodiment amongst Korean military brides.

Figure Four: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 14-17)

Figure Four: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 14-17)

left images (pages 14, 15) introduce the passage with a translational command blurring between religious motifs, French history, and personal anecdotes. As the progression continues, the right images (pages 16, 17) transitions to detail seeming reenactments of confession and finishes the passage off with a transcript expressing the nature of God and creation

In reiterating a previously stated point, it is worthwhile to consider how notions of dictation can be seen as a potentiality for transformation. Cha’s work brings together elements of French Catholicism and the significance of selves as a means of highlighting the “body as a site of colonial witness” (Cha 1950: 14-17; In Alarcón 1994, et. al 1994: 87). Catholicism, an institutional power that has been used to produce subjects faithful towards obedience, is interrogated as a means of understanding what it means to experience the position of religious subjection as it intersects her multiple positionalities. In so doing, Cha takes on the responsibilities of multiple tongues and the roles of “storyteller, a scribe, a transmitter” to use the knowledge she has been prescribed to create space while simultaneously subverting the pedagogical control these institutions enforce (Cha 1950: 14-17).

The multiple responsibilities Cha embodies converses with the delineation of selves Korean military brides negotiate. Given the history of Japanese colonialism and US militarization in Korea, many Korean military brides are able to speak two to three languages. In Yuh’s ethnographic research, when the women are asked about how their cultural identity is maintained, many of them respond by saying they can speak in Korean, eat certain dishes, and watch Korean entertainment during the hours when their husbands are not home (Yuh 2002: 231). More so, many Korean military brides express a sense of compartmentalization when it comes to their identity being a Korean woman, a wife to an American soldier, and an Asian woman living in America (Yuh 2002: 231). Their language, cultural practices, and expressions of self are monitored in domestic spaces and controlled under the supervision of the husband’s family.

Figure Five: From Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 20)

Figure Five: From Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 20)

image (page 20) interrogates notions of one’s identity as it relates to the geopolitical, genealogical, and sociocultural construction of selves

In dialogue with the literature, Cha’s intentional destabilized depictions of home, self-origin, and nationhood bring into question how the space in which she is undermining creates a new possibility for being. Outside of the house, Korean military brides have found an alternative space where the entirety of their identities are understood, validated, and cherished. Korean military brides across the US have found communities where they retell their stories, share their experiences living in the US, and offer comfort for those seeking support (Yuh 2002: 170). In employing the sociological imagination, the positionalities of these women are better understood in context to the biographies and histories they carry (Mills 2000: 1). Given how the institutional structures of the Korean government pressured Korean military brides to immigrate, followed by the domestic policing of Korean cultural practices by their husbands, the strategies in which these women employ to maintain their identities are better realized in context to their collective biographies. Excluded from Korean Churches, Korean military brides living in/near military bases – such as Fort Brag in North Carolina, Fort Riley in Kansas, and Fort Sill in Oklahoma – created support groups for Korean military brides who recently immigrated, community Korean cook-outs, and fundraising events to help support Korean military brides who may be in financial need (Doolan 2020: 91; Yuh 2002: 212; Takagi 1995: NA). Their identities, existent between multiple crossroads, are wholly welcomed in the spaces these women have created for one another.

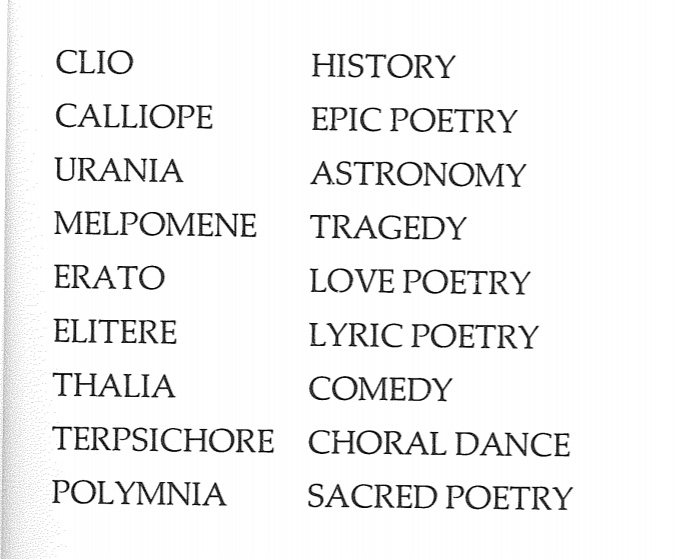

Figure Six: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: x)

Figure Six: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: x)

image (page x) depicts the overarching organizational structure of the novel. Each chapter is named after a Greek Muse, which in Greek Mythology were often storytelling figures narrating male-centric tales of trials and triumphs. Cha’s inversion of such roles and employment of female storytellers to narrate her story highlights the space of female-centered experiences Cha is seeking to create

Conversing with Dictee, Cha’s intentional organizational strategy to name each chapter after a Greek Muse highlights the female-centered narrative Cha is aiming to highlight. Within the overarching canon of historical literature, male-centric voices too frequently take space when detailing the lived experiences of a given community. As with the case of Greek muses, the muses were employed to accentuate the epics of male heroes within the Greek canon with seldom acknowledgment to female heroines, let alone the muses narrating these stories. As seen in Figure Six, Cha uses the mythos of Greek muses to narrate the experiences of female Korean revolutionaries and her experiences side by side (Cha 1950: x). Dictee is hence seen as not just a literary work on post-war diasporic experiences, but as a feminist piece of literature that focuses on Korean women’s voices on post-war diasporic experiences – Cha is creating space for her voice. Amidst the surveillance Korean military brides face, these women similarly create space for their identities and experiences to be expressed in such a way that destabilizes traditional gendered narrative establishments.

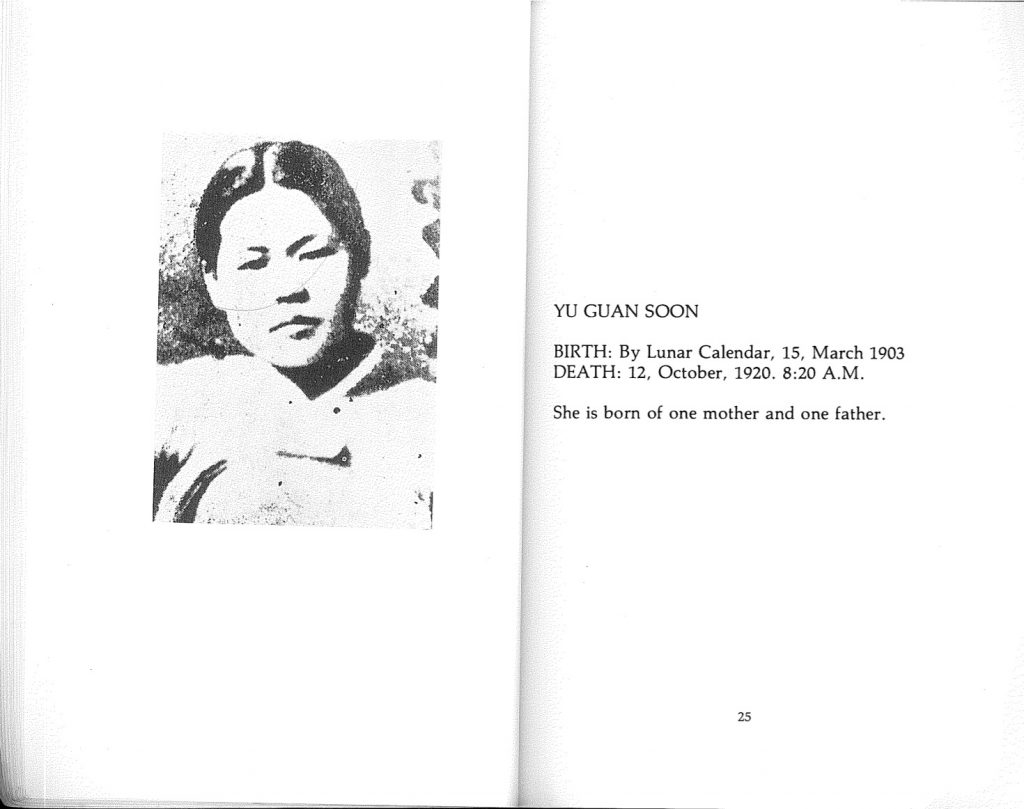

Figure Seven: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 24, 25)

Figure Seven: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 24, 25)

left image (page 24) is of Yu Guan Soon, a female revolutionary activist and political organizer against Japanese colonial rule; right image (page 25) is a translated memorial to what is typically written on Korean gravestone markers. Yu Guan Soon died at the age of 17 from prolonged torture and abuse from Japanese prison guards

In continuation, Cha’s narration of war through female revolutionary figures insists on the existence of the Korean women’s experiences, a history that is often oversaturated from a male-centric vocality (Cha 1950: 24-25). Her use of the female narrative permeates patriarchal borders that aim to filter histories of the Korean War and propagate ideologies of US liberal freedom. While Yu Guan Soon is a revolutionary figure during Japanese colonialism, her narrative, likewise to Korean military brides, is left out by mainstream depictions of Korean history. Similar to how narratives of the Korean War focus on the US nation-state as the “protector” and “liberator” of the Korean peninsula, and not of the militarized violence the US government enacted upon the Korean people, Yu Guan Soon’s story is conversely untold in the liberation of Korea (Cho 2008: 37). Cha’s integration of Yu Guan Soon’s photo and her memorial marker creates space for the insistence of Soon’s presence to be made. As it relates to Korean military brides, both the Korean and US government do not formally acknowledge the role both nation-states had in the formation of Camptown prostitution and the lives community members within those towns had to lead (Yuh 2002: 145; Takagi 1995: NA) Amidst continued militarized experiences of US military bases, the creation of space for Korean military brides by Korean military brides challenges dominant narratives that seek to erase their identities.

Conceptualizing El Nie amongst Korean Military Brides

Cha’s reconciliation of multiple worlds is embodied within Itzigsohn’s understanding of diasporic Dominican experience in the US, but also with Simmel’s stranger and Josefina Baez’s El Nie. Earlier in this paper, discussions of “third space” and alternative forms of being were introduced – those points all lead up to El Nie. El Nie is what Baez defines as an “imagined space” where memories and experiences of the present offer a collective retelling of the immigrant experience (García-Peña 2016: 180). In direct correspondence to Cha’s notion of the third space, García-Peña characterizes El Nie as the “space that exists at the margins,” where hybridity is used as a means of resisting “hegemony from within the nation(s)” (García-Peña 2016: 183). As previously mentioned, the literary/aesthetic tactics employed in Dictee similarly integrates the hybridity of the tongue to subvert structures of pedagogical violence.

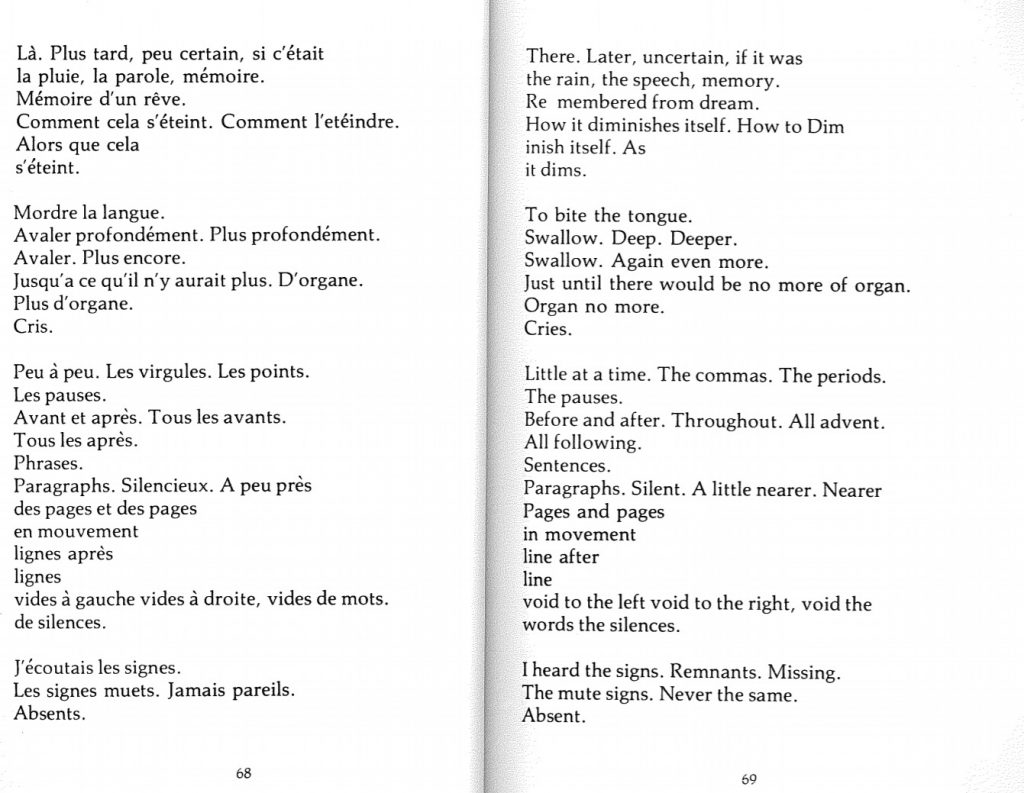

Figure Eight: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 68, 69)

Figure Eight: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 68, 69)

left and right images (pages 68, 69) are translations of one another that utilize both French and English as a means of accentuating the hyper-punctual commands in pronunciation and grammar. Signification is placed on the pedagogical discipline of the body as a means of producing legible sounds and grammatical structures

In Figure Eight, the seeming delineation between French and English is neatly compartmentalized between both pages, where seeming correspondence suggests a form of translatability. Existent within each individual page, French and English are separated by the literalized border created from the book’s binding. However, the border between both pages are not apparent, but suggestive through the page break of the two texts. Such aesthetic strategy expresses the simultaneous control and containment of linguistic commands and is synonymous with the strategies Korean military brides employ in maintaining their practice of the Korean language. The disciplining of the tongue Korean military brides experienced was enforced commonly by their husbands and “educational centers” as a means of turning the “foreign” subject into legible bodies in white America (Yuh 2002: 130; Takagi 1995: NA). Many Korean military brides expressed how speaking Korean within their own home was looked down upon and commonly forbidden by their husbands (Yuh 2002: 137). However, maintenance of the Korean language was ensured by speaking the language to their children when their husbands are not home, and organizing meetups amongst other Korean military brides near military bases (Yuh 2002: 261; Doolan 2020: 90). Such negotiation of the multiple selves corresponds to Josefina Baez’s construction of El Nie. El Nie, defined as the “invented space that exists at margins” converses with the social practices Korean military brides engage in, where the maintenance of their identities is at the borderlines of acceptability/unacceptability and legibility/illegibility by their husbands, normative Korean communities, and American society at large (García-Peña 2016: 190). Such understanding further compliments Itzigsohn’s conceptualization of ethnoracial stratification, where the navigation of cultural practices and disciplining of identities is in part due to structured inequality and hence the lack of accessibility to such resources (Itzigsohn 2009: 51). As this relates to class situation and communalization, the positionality Korean military brides occupy as Asian women in predominantly white military towns highlight the limitations to resources these women face when engaging in cultural practices (Weber 2013: 187). Through communalization of other Korean military brides, those resources and community networks become more accessible not just within these military bases but across other fort towns as well (Weber 2013: 190; Yuh 2002: 261; Doolan 2020: 97).

Figure Seven: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 63, 74, 75, 78)

Figure Seven: from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (Cha 1950: 63, 74, 75, 78)

left image (page 63) is a human body meridian map used in Traditional Chinese Medicine; center left image (page 74) is an anatomical diagram of the throat; center right image (page 75) are instructional cues commanding certain throat registers; right image (page 78) is a mapping of the Korean peninsula after the armistice in 1953. The audible sounds produced are not placed in heavy importance, but rather, the disciplining and control of the body is seen as the primary objective

The significance El Nie places on the body, location, and language conversely engages with Cha’s interrogation of “geographical [imaginaries] and historical spaces” as both are enmeshed within understandings of the body (Cha 1950: 21; Alarcón, et al. 1994: 71). As seen in Figure Nine, Cha utilizes medical mappings of the body to contextualize not only the bodily discipline she has endured through western pedagogical instruction, but demonstrates the cartographic weight the body holds as a site of memory, home, and belonging. Following the medical illustration on page 74, page 78 shows a map of the Korean peninsula in its divided form following the armistice agreement in 1953 (Cha 1950: 78). The intentional choice to visualize a divided peninsula further complexifies the split positionalities Cha occupies. The cartographic entanglement of the body, language, and one’s nation-state characterizes not just the resiliency of Cha’s identity, but the space she is creating to make her presence known – the creation of El Nie.

Trangressional haunting, a term used to detail the proliferation of memory across non-singular axis points of time/space, converses with Cha’s depiction of memory as intertwined on one’s body, language, and landscape (Cho 2008: 30). The geopolitical traumas of the Korean War are visualized through the map of a divided peninsula, yet Cha makes the choice to embed cartographic depictions of the body and foreign linguistic commands side by side. Such literary/aesthetic strategy invites us to reconsider the ways trauma persists beyond the strictly geopolitical and is intimately intertwined with the subjective body. Cha’s cartographic entanglement asks us to look beyond the neat delineations of memory and questions us to imagine how and where memory is stored. Following the map on page 78, Cha writers a letter to her mother as follows:

“I speak in another tongue now, a second tongue, a foreign tongue. All this time we have been away. But nothing has changed. A stand still… the population standing before North standing before South for every bird that migrates North for Spring and South for Winter becomes a metaphor for the longing of return. Destination. Homeland” (Cha 1950: 80)

The intersection of the historical and rhetorical as interwoven elements births new poetics for Cha’s own truth to take place. As this converses with Korean military brides, it is important to consider how envisionments of home are similarly entangled with cartographic conceptions of belonging. Prior to US immigration, most Korean military brides had prior histories as Camptown prostitutes in US military bases (Yuh 2002: 31). Seeing marriage with US soldiers as a possibility to leave such conditions, many found themselves in another military town with little to no resources to Korean cultural practices or networks (Yuh 2002: 131; Doolan 2020: 90). Towards mapping a future free from the violence of US militarization, many of these women found themselves further entangled within the geopolitical landscapes they were trying to depart from. The charge of military violence never left the lives of these women, but rather became the lived realities of the everyday – spaces of the domestic and the public became interwoven. In maintaining sociality amidst the surveillance of US military towns, many of these women redefined what it means to engage in Korean cultural practices and cultivate community amongst one another. From using canned army rations in place of traditional Korean ingredients to weaving Korean traditions into American holidays, Korean military brides created their own space that offered sanctuary amidst the harsh realities of daily life (Yuh 2002: 150; Takagi 1995). Like Cha, these women created their own El Nie.