5 organization as brain

Critical Questions

-

Is it possible to create organizations that learn from themselves and have the capacity to be as resilient, flexible, and inventive as the human brain?

-

Is it possible to distribute capacities of intelligence, control, innovation, and feedback throughout an entire organization so that the system can self-organize and evolve with emerging challenges and changes to the environment?

Organizations can, and should, be thought of in many different ways. The different metaphors we use to examine and understand organizations in this book each highlight unique strengths, weaknesses, and approaches to organizational work.

In this section, we will see how the brain’s adaptivity, resilience, collaboration, ability to learn, and specialization plays out in organizations.

The brain is a metaphor that tells us about how we interact as individuals within a group. All of the theories we discuss in this chapter can be applied on a personal level and it’s important to try to apply these concepts to the self first and foremost.

Metaphors That Make Simple Sense

“If broken, any single piece can be used to reconstruct the entire image. Everything is enfolded in everything else, just as if we were able to throw a pebble into a pond and see the whole pond and all the waves, ripples, and drops of water generated by the splash in each and every one of the drops of water thus produced” (Morgan 73).

Embracing the “whole in parts” theory decentralizes control in organizations which is conducive to growth and success. This happens because the organization is forced to store and process information in all areas of functioning. From the bottom up, patterns of innovation and production emerge from the process, rather than imposed and rigid managerial structures.

The most beautiful aspect of “whole in parts” is the paradox it embraces between specialization and holographic. Within this way of operating there is still room for specialization!

Why is specialization important?

- Increases productivity and product quality (keep an open mind when considering different products)

- Develops care and compassion in what we do

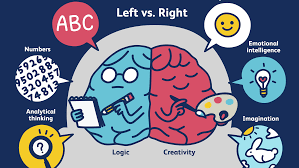

| Right Brain | Left Brain |

|---|---|

| Creative, intuitive, emotional, acoustic, and pattern recognition functions and controls the left side of the body. | Rational, analytic, reductive, linguistic, visual, and verbal functions while controlling the right side of the body. |

| Specialization | Generalization |

| Marketing research and product development | New products! |

Think about an organization you are currently part of: it could be your workplace, your college, your family, or anything that comes to mind. Now think of the culture of this organization- the implicit norms, assumptions, and values that dictate the way it functions. Does this culture capture the norms, assumptions, and values of the people within the organization?

As I reflect on the organizations I am part of, I find that their operating norms do not reflect the values of the people within them.

Although all four of the people in my immediate family have become a lot more egalitarian in their thinking, this change fails to reflect any meaningful alterations to our family’s patriarchal structure. Or, as I think about the individuals that attended Claremont McKenna, my college, 30 years ago and the individuals that attend it now, I don’t see the norms of the institution changing at a fast enough rate to reflect the values of the student body.

Why is that? Why do organizations sometimes fail to learn and grow alongside the people within them? That is the subject of this section: to look at the roadblocks to organizational learning and contemplating ways to make organizational learning processes more like that of a brain.

How do organizations learn?

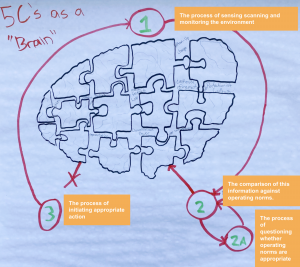

Morgan, in his chapter on Organization as Brain, provides a framework with which to understand how organizations learn. He claims that most organizations fall into the trap of single-loop learning. (see left diagram below)

If you slide the bar, you will see what is called double-loop learning. Organizations that engage in double-loop learning are able to not only scan their environment and adjust according to some preexisting operating norm but to question the operating norm itself!

Let’s break this down a bit by turning to the metaphor of brain and cognition. Think of a route that you walk or drive every day, or one for which you did this in the past. Say it is your path from your dorm to your class. Every day, you walk from your dorm to your class building at 9 am. The route is fixed in your head and you can navigate walk it while listening to music or cramming for a test. Walking this route based on memory operating norm.

Now imagine there a renovation taking place at your class building, and your class gets relocated to the other side of campus that you barely ever go to. Will you use the same method (of relying on your memory) to try and find this new building? You might. But a lot of people would find a more efficient way, like asking a friend, using a campus map, or even trying a navigation app. Here we are changing only our route, but the way we navigate- ie our operating norm! Human brains have a remarkable capacity to change and adapt to situations like this. We are constantly reworking our operational norms based on input from our environment.

Now let’s look at a more complex example at an organizational level. The “preferences and fears of white European descended people overwhelmingly shape how we organize our work and institutions, see ourselves and others, interact with one another and with time, and make decisions.” (Okun & Jones, 2019). One of these preferences is that of individualistic leadership, i.e. a focus on “single and charismatic (and mostly white) leaders working in, isolation from each other and from the organization.” Even in the case where most people in an organization are of the belief that leadership should be more diverse and more geared towards the collective, the organization can still fall back on that operating norm of individualistic, white leadership. Colleges are a great example of this. As colleges become increasingly diverse and value diversity more than ever, the white male leadership norm has stayed relatively constant.

White male leadership norms have remained at the 5C’s and manifest themselves in the lack of action pertaining to the requests and values of non-white students. There is a fracture in the supposed double-loop learning process at the 5cs between steps 2 and 3 of the loop. The 5C’s are able to compare information against operating norms as well as question the appropriateness of those norms but fail to institute action based on those assessments. This shows itself in the lack of action the schools have taken on the requests of the BSU. As PZ ’23 student Solange Baker said, in The Student Life, “There have been 52 years to implement the improvements and changes listed in the 1968-9 demands and yet here we are asking for the same things.”

Exercise 1

- What would double-loop learning- i.e rethinking operational norms- look like in the case of colleges and their leadership? Is it having a more diverse leadership? Or is it more radical, like getting rid of the leadership and letting students make their own decisions?

- Or do you think the current system of leadership is most appropriate for colleges to meet their aims? (Remember, double-loop learning is the ability for change and reflecting on norms. This reflection process doesn’t have to result in changing the norms if they are still suitable.)

So what prevents organizations from changing their operational norms and engaging in double-loop learning?

According to Morgan, it’s bureaucracy.

In a bureaucratic structure…

- All processes are formalized

- power is pyramidal and concentrated at the top

- Rules and responsibilities are clearly stated

- Members of the organizations divided into disconnected subunits

- Situations that challenge policies and operating standards are exceptions

This is dangerous. The sections can end up doing completely different things and getting in each other’s way in destructive manners that will cause the collapse of the entire organization. To be the whole in parts, learning to learn must be a core value. Learn from yourself, your teammates, and people on different teams.

This structure obstructs the free flow of knowledge where each “sub-unit” is pursuing its own individual goals without thinking of the larger organizational vision. Emphasizing the difference between sub-units of an organization creates competition and politics, and goes against a collective vision.

Exercise 2

1. Do you agree? Do you think the bureaucratization of organizations makes it hard for them to learn?

2. Can you think of some ways in which bureaucratic processes inhibit learning in the organizations that you are a part of?

3. What are some other explanations you can think of for why organizations fail to learn and adapt?

Learning Organizations

SUMMARY: What do we need to do to have a learning organization?

- Scan and anticipate change in the wider environment to detect significant variations.

- Develop an ability to question, challenge, and change operating norms and assumptions.

- Allow an appropriate strategic direction and pattern of organization to emerge.

Evolve designs that allow organizations to become skilled in the art of double-loop learning, to avoid getting trapped in single-loop processes, especially those created by traditional control systems and the defensive routines of powerful organizational members.

The world would be a boring, sad place if we refused to learn to learn. It’s not a matter of whether or not we can do it, it’s whether or not we’re willing to do it.

Learning to learn breaks down the strict hierarchy and horizontal divisions of power and communication we frequently find in organizations. Information, creativity, success, and development are pushed into small and rigid sections of the organization when the ability to learn from one another has been lost through stiff hierarchy. When these divisions are present each sector operates on its own concept of organizations goals and ethics.

Here is Peter Sange, author of the Fifth Discipline (The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization) talking about learning organizations, questioning mental models, and achieving collective intelligence.

To achieve this kind of collective intelligence and growth, the first step is to uproot bureaucratic structures and replace them with structures that facilitate learning.

There is no prescribed formula for how to do this – but we can start by asking some basic questions (inspired by Okun and Buford (2019)). Hover over each aspect of a bureaucratic organization to see a question we can ask to start to change this and move towards a structure that facilitates learning

And hopefully, the answers will lead us to create organizations where:

- The environment is scanned and change is anticipated and embraced

- Operating norms are challenged

- Knowledge is constantly discovered and created by all members of the organization

All that we have just told you, about learning to learn and double and single-loop feedback specifically, is at times contradictory, confusing, and just too much to take in. That’s why in the 1940s a mathematician named Norbert Wiener, interested in the ways humans treat each other and feedback learning, created cybernetics.

One of the integral parts of cybernetics is the power of negative feedback. Humans tend to make decisions based on what they wish to avoid. For instance, I go get a hot dog because I don’t want to be hungry. This decision-making process alone can at times be problematic because it doesn’t allow us to fully pursue our highest aspirations.

In order to counteract this pessimistic, survival-based thinking, we use positive feedback. Positive feedback would lead me to get a hot dog just because I like the taste of it. Of course, if we operate on positive feedback alone, we risk neglecting our basic needs.

Why Mr. Wiener May Have Over Emphasized Negative Feedback

Negative feedback eliminates error: it creates desired systems, patterns, and outcomes by avoiding messy and unpredictable patterns.

Similar to the left and right sides of the brain, both positive and negative feedback are important for making balanced decisions that will benefit an organization as a whole.

HEY! If you’re interested, there’s some really cool science behind all this stuff. It’s not crucial in understanding how positive and negative feedback works, but it will definitely enhance your understanding.

-

Systems must have the capacity to sense, monitor, and scan significant aspects of their environment.

-

They must be able to relate this information to the operating norms that guide system behavior.

-

They must be able to detect significant deviations from these norms.

-

They must be able to initiate corrective action when discrepancies are detected.

TAKE A BIG DEEP BREATH. THIS IS SO MUCH INFORMATION. NO MATTER HOW YOU’RE DIGESTING IT, YOU’RE DOING A GOOD JOB.

Conclusion

How do you feel about the brain as a metaphor for organizations? Did it encourage you? Or discourage you? Is there anything you’re going to change about your life after reading this?

Here’s how it affected us…

Georgia: Thinking about organizations like this made me happy. Some parts were so overlapping, conflicting, and messy that it actually took the pressure off understanding why and how things happen the way they do. My favorite quote from the text we got all this information from is “Better to run clumsily than not at all.”

Shania: As a psych major, I loved thinking about organizations in terms of the brain. I think it was an optimistic and hopeful lens and allowed me to think of my ideal organization- which was a nice change from the “we’re doomed” view that some of the previous metaphors left me with!

Zach: I enjoyed the organization as brain metaphor because it gave a positive view of organizational interaction which allowed me to examine the 5Cs and some of the issues we experience here with a new perspective.

Amya: I like the brain metaphor because it focuses on specific concepts like single and double loop learning. There are clear lines that tell us where the brain metaphor begins and ends, but we are still able to draw in our personal experiences similarly to the other metaphors.

Sophie: I appreciated the brain metaphor because of the unique perspective it brings to organizations. Many of the metaphors we looked at in this class portrayed much more conventional or “traditional” organizations that reinforce a hierarchical society, but the brain metaphor moves away from that, focusing on a more holistic and inviting approach to organizations.

Jason: I believe the brain metaphor is important because of the sense of hope it brings. Members of an organism are working together and using their combined intelligence in order to predict change and develop a learning organization, which I believe is a great way of looking at organizations.

Michael: I really like the brain metaphor because, unlike a lot of the other metaphors we’ve learned about in this class, it provides a sense of optimism towards organizations: they are not always hierarchical, exploitative, and dominating structures.

GIVE US YOUR FEEDBACK AND FEELINGS PLEASE! Email brainorganizationmetaphor@gmail.com

We will respond. If you email us within the year of 2020 we will take no longer than a week to respond. If you email us any time after 2020 it could be a several month response wait time.

FOR QUESTIONS IN 2021 PLEASE REACH OUT TO US @

Mross@students.pitzer.edu

Zcohen@students.pitzer.edu

Sdorn@students.pitzer.edu

Jkennel@students.pitzer.edu

mbolden@students.pitzer.edu

Created by Amya Bolden, Zach Cohen, Sophie Dorn, Tia Greenfield, Jason Kennel, Michael Ross, Georgia Scott, and Shania Sharma

Last edited: Dec. 1, 2020