4 organization as organism

Organizations as Organisms

What is an organism?

According to Merriam Webster, an organism is “a complex structure of interdependent and subordinate elements whose relations and properties are largely determined by their function in the whole.” In this view, certain organizations are better adapted to specific environmental conditions than others.

In this chapter we will use biology as a source of ideas for thinking about organizations.

What is organization as an organism?

Collective thoughts from our class notes & quick writes:

In general, this organism view is more analytical and less critical because it does not make assumptions about power. Rather, it has a holistic approach and it brings to attention how organizations are collaborative efforts.

Did it ever occur to you that biology can be a source of ideas for thinking about organization? In this chapter, we highlight the importance of understanding how organizations function and the factors that influence their well-being from a ecological perspective.

The organization as organism view shifts our focus from goals, structure, and efficiency to more general issues of survival, organization-environment relations, and organizational effectiveness. Things such as goals, structure, and efficiency become secondary in the face of such biological considerations.

In the following sections of the chapter, we have included various examples to help explain the org-as-organism metaphor. We want to stress the importance of seeing this metaphor as not only a way to view the organization of companies and businesses, but also a lens that can be applied to other forms of organizations as well — for example, resistance groups, communities, and the ecosystems of the natural world.

Organisms are holistic

In a living organism, there are many subsystems such as molecules, cells, and organs. Now that we have defined the whole organization as a system, organizations also can be viewed as different interacting subsystems. Each needs its own management styles for its unique environment. Here are some ways of integrating the needs of individuals and organizations to foster personal growth:

Theories of Motivation (organizations satisfy needs)

The Hawthorn studies in the 1920s revealed the relationship between conditions of work and the incidence of fatigue and boredom. These studies are significant because they reveal the importance of valuing and meeting social needs of people in the workplace.

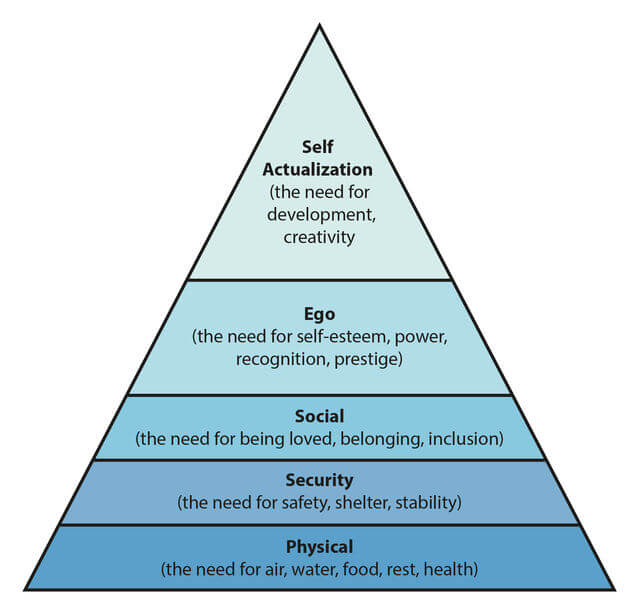

Similarly, Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs shows us that, in human beings’ quest for full growth and development, they must strive to meet their basic human needs first. Individuals and groups, just like organisms, operate best when their needs are satisfied. Thus, thinking about the hierarchy of needs can help organizations think about how to best motivate and care for employees. In particular, organizations should strive to meet their employees basic needs and also make them feel important by providing them with autonomy, recognition, and democracy.

The same logic can be applied to neighborhood communities: if people within the community aren’t well supported and their needs remain unmet, the community as a whole will feel the impact. In Johnson City, Tennessee, movements such as the “Confess Project” support Black men in the community by giving them a safe place to open up emotionally. Communities can support themselves by recognizing everyone within them as holistic individuals and making sure their needs are met.

Contingency Theory (adapting organization to environment)

The Contingency Theory suggests that management style should be “contingent” or dependent on the internal and external situations. The contingency theory promotes organizational health and development by understanding that organizations are interrelated subsystems. Organizations are open systems that require careful management to balance internal needs.

Therefore, the theory focuses on adapting the organization to fit the environment. Leaders are trying to find a “good fit,” ever conscious of the dynamic environment and understanding there is no one way to best organize.

This is in contrast to other metaphors, such as organizations as machines, where roles are tightly defined within the organization. The organism metaphor treats roles as dynamic, changing in order to meet the needs of the organization in order to achieve “survival.”

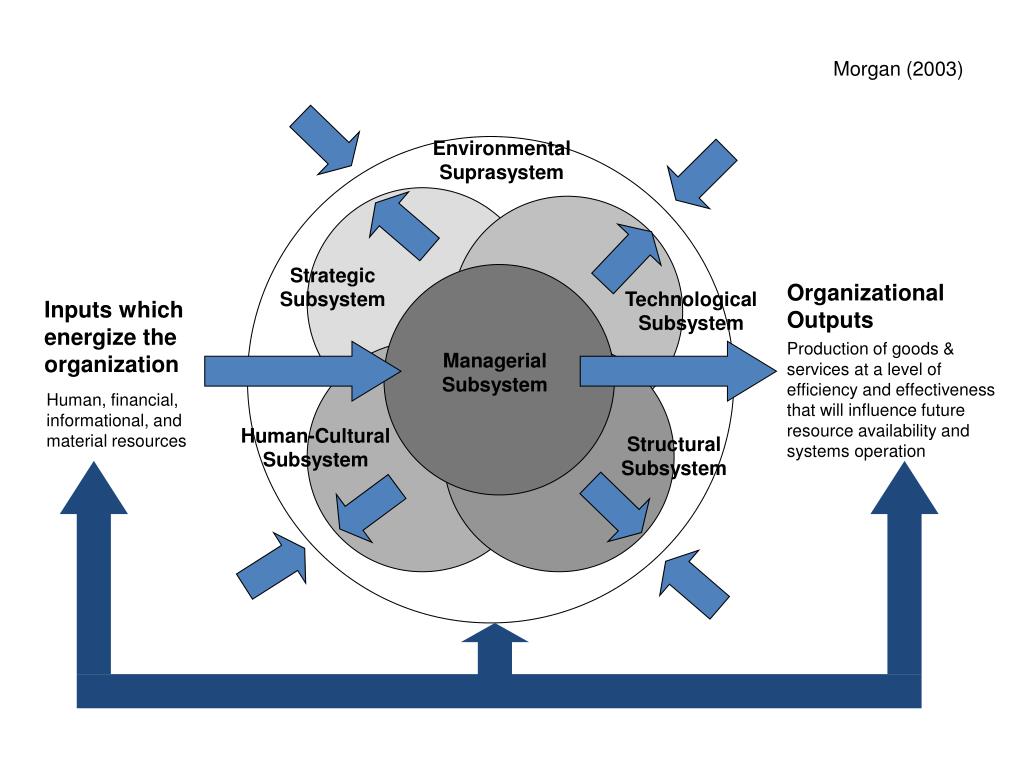

Organismal Connections

The metaphor of organizations as organisms highlights the complex relationship between an organization and its surrounding environment. Cells, organs, and even entire living creatures are all parts of living, “open systems,” “characterized by a continuous cycle of input, internal transformation, output, and feedback. (Morgan, 2006). Organizations, like the open system of a living organism, also have similar processes of input, transformation, output, and feedback. Instead of nutrients necessary to sustain life, organizations take in human, financial, informational, and material resources and transform those resources into organizational outputs. This process makes the organization susceptible to its environment in a variety of ways. Looking at organizations as organisms emphasizes the importance of analyzing organizations with the facets of their environments in mind. Through this metaphor, attention is turned away from the goals, structures, and efficiency seen in more classic management styles and placed on the needs of the organization and its subsystems.

External relationships

To start we will look at the whole of organizations and then move into the smaller divisions within them. Organizations as a whole are seen as having external concerns or needs that are both fulfilled and defined by the environment. The challenge that initially arises is defining the external concerns of the organization. Morgan lists the defining factors of external organizational concerns as the “tasks of the organization as a whole which are defined by the organization’s direct interactions with customers, competitors, suppliers, labor unions, and government agencies, as well as broader ‘contextual’ or ‘general environment’” (Morgan, 2006). This list however seems limited by an assumption Morgan makes about organizational outputs. If organizational outputs are defined as “production of goods and services at a level of efficiency and effectiveness that will influence future resource availability and systems operation.” It seems the obvious corollary is that resource availability is at risk and that organizational “tasks” must be competitively oriented towards production, sales, and economic survival of the organization.

What would happen if we redefined organizational outputs to focus less on the production of goods and services and more on the health of the community (i.e. social justice, mental health and happiness, or environmental and climate justice)? Organizational “tasks” as a whole might be shifted to realign the larger global and local needs of our communities with the general survival of the organization.

Internal Subsystems

Organizations often default to efficient profit-based styles of organization centered around production because the primary environment most of them exist in is part of the large, competitive global economy. To try to shift towards a more subsistence-based organization, looking at the subsystems within an organization can help highlight strategies to shift our framework for understanding organizations from production and profit, to subsistence and fulfillment.

The subsystems within an organization are made up of various levels of sizes including individuals, groups, departments, or any other organizational division, can be seen as smaller interacting subsystems. Some recognizable examples of different subsystems are the divisions made between managerial, human-cultural, structural, technological, and strategic groups within an organization, but subsystems can be defined in many different ways. The importance of defining and looking at subsystems is that once they are identified, the interactions between different configurations of subsystems can be altered to better align with the needs of the smaller parts or individuals and the larger organization. Systems theorists use different principles of subsystem design that utilize key proponents of success for various organisms in nature, to inform these alignments. Through these principles, the organization can be adjusted to perform tasks effectively with the surrounding environment in mind.

There can be friction with how the primary tasks of the organization are identified. Morgan writes that, “the design and management of subunits must accommodate the primary task of the organization as a whole rather than the reverse.” This is a scary proposition, if the primary task of the organization depends on profit, environmental degradation, and social injustice. By altering the basis the org-as-organism metaphor is defined on, it might encourage a culture of subsistence and community wellness over greedy corporate profit within our organizations. This shift would hopefully emphasize a more equal distribution of resources both within and outside of the organization.

Indigenous wisdoms speak of the importance of making sure that the rest of the community can share the wealth. In Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, the author talks about her knowledge of the Anishinaabeg practice of Honorable Harvest, a practice of only taking as much as one needs:

- Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them…

- Never take the first. Never take the last.

- Take only what you need…

- Never take more than half. Leave some for others.

(Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer, 2013)

When harvesting in the wild, these rules provide the plant with the ability to stay healthy and not suffer from over-harvesting. By being harvested only halfway, the plant actually has more space — it encourages growth. By not taking the first or last, we can be sure not to kill off the whole plant species. It then can continue to provide for others after you. This way, one is fulfilling their own needs while also providing the opportunity for everyone else in the organization to fulfill their own needs as well.

Population Ecology Theory

Morgan explores the idea of the “population ecology” view of organization which holds that companies must adapt to their environments in order to survive. This view follows the logic that, due to resource scarcity, organizations must compete over limited resources and that through natural selection only the fittest — those with the competitive advantage or that are most adaptable to the changing demands of the market — will be able to survive. Under this view, the environment of competing organizations is a critical factor in determining which organizations ultimately succeed or fail.

Key to the population ecology view of organization is the idea of scarcity. While scarcity mindsets are widely accepted — to the point that they seem natural to many, — we acknowledge that it is important to challenge this assumption and consider the consequences of operating based on the individualism and hyper-competition that this mindset can encourage. Morgan briefly brings up this critique of the population ecology view in his writing:

“The emphasis on resource scarcity and competition, which lie at the basis of selection, underplays the fact that resources can be abundant and self-renewing and that organisms can collaborate as well as compete” (Morgan, 62).

Based on this critique we will briefly explore the difference between scarcity and abundance mindsets and how these differences can impact organizations and their actions.

Scarcity Mindset

The scarcity mindset is the idea that there are a limited amount of quality resources. This way of thinking often creates an environment of competition that pits people against each other in a fight to secure and stockpile those resources.

This mindset perpetuates and protects itself in two major ways. Firstly, it is effective in keeping people in silos — distracted by the constant need to compete and secure resources for themselves and their families, people often remain isolated from understanding how their experiences and struggles connect and overlap with those of the people around them. Secondly, this mindset allows people who benefit from the current structure, i.e. wealthy white folks, to justify their “successes” as deserved and earned. The idea that wealthy people deserve their wealth due to their merit and hard work alone, or meritocracy, also ignores structural realities and reinforces the underlying falsity that it is the fault of poor folks for not being able to attain economic mobility. This mindset allows people to treat individualistic or privatized solutions as if they are justifiable and common sense. This perpetuates a cycle where people make decisions in order to try to provide the best for themselves rather than pushing for overall systemic change that would create better conditions for everyone.

When talking about organizations people often try to frame hyper-competition as natural through comparisons to places competition shows up in the natural world — such as male lions competing to lead a pride. However, while examples like these are common, people often fail to acknowledge the many places in nature where organisms thrive through reliance on community support and collaboration rather than on individualism and competition. For example, organisms that work together, such as fungi, are actually some of the most resilient and widespread organisms on our planet. In Emergent Strategy, Adrienne Maree Brown summarizes this, writing:

Adrienne Maree Brown writes, “We learn to compete with each other in a scarcity-based economy that denies and destroys the abundant world we actually live in” (Brown, 48). While it is true that in certain ways there are limited resources on planet Earth (we are experiencing the consequences of people’s continual over-extraction of resources through climate change), the true problem that a scarcity mindset creates is the reliance on individualistic mindsets and “solutions” that have negative impacts on wider systems and communities as a whole.

Abundance mindset:

An abundance mindset is the idea that there are enough resources for us all to share and be able to thrive together. This idea does not rely on a false assumption that there are unlimited resources in the world but rather on the idea that there are enough resources for us all to all be able to access security. There is an interesting dynamic between a mindset of abundance and an increase in generosity and community care. This mindset relies on an idea of collaboration, in contrast with that of scarcity which sets up competition and individualism as necessary for survival, justifying taking from others and defending what you have.

To highlight the difference between abundance and scarcity mindsets we can consider the following quote from Adrienne Maree Brown:

This quote explores the competition for survival dynamic that is set up by scarcity thinking. In contrast an abundance mindset asks us to think not in a matter of whether we have enough resources but rather how we use the resources that we do have and continue to innovate. Through investing in community infrastructures and supports such as affordable and quality access to food, water, healthcare, childcare and eldercare we can create communities where everyone’s basic needs will be met.

For example, we can consider the United States’ spending — as one of the wealthiest nations in the world — and what resources and protections it provides/doesn’t provide to its inhabitants. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 2020 “US military expenditure reached an estimated $778 billion.” That means that each day in 2020 the US is spending over 2 billion dollars on funding military operations. This is over double what any other nation in the world spends on their military budget (Source). The US doesn’t only lead the world in military spending but also in rates of incarceration. The Bureau of Justice Statistics has calculated that the US “spends more than $80 billion each year to keep roughly 2.3 million people behind bars. Many experts say that figure is a gross underestimate, though, because it leaves out myriad hidden costs that are often borne by prisoners and their loved ones, with women overwhelmingly shouldering the financial burden” (Source). While the US leads in military and carceral spending, we fall behind in areas like education and healthcare. According to Forbes, 13.4% of the national population in the United States lives below the poverty line. An abundance mindset invites us to ask ourselves how we can use the resources that we have to invest in care and not continual violence. Through this mindset we understand that we have everything we need to make positive change already here. The world would be transformed if we used our resources to focus on meeting peoples needs like ending poverty, and providing access to resources like safe and healthy food and water, quality education, and safe and affordable housing.

Application: Resistance movements

We can also use this metaphor when thinking about the organization of resistance movements. When organizing social movements, the organization as a whole must stay true to its goals and maintain forward momentum, however, keeping the movement alive also requires each individual within the movement to receive the care and resources for their basic needs to be met. In her book Radiating Feminism, Beth Berila reminds us of the importance of caring for oneself while also fighting for larger movements. It’s important to keep our own personal wells full and to meet our own needs before we are able to tend to others. Resistance work can be exhausting, and social groups need their members to practice self and community care to be able to keep up with the demands of the work and emotional labor required by social movements. Living in a scarcity mindset can make people, especially those confronting great injustices, feel as though they are in time famine. This phenomena can push people to keep going, keep working beyond their own personal limits, which is ultimately unsustainable for both the individual and the movement as a whole. When we begin to think of time as abundant and movements as part of generational tapestries of change making, we are more able to give ourselves time to heal, reflect, and care for ourselves and our communities. This mindset can also give us more opportunity to see and practice our interconnectedness.

To draw an example from nature, Adrienne Maree Brown quotes Naima Penniman in Emergent Strategy:

Berila encourages the cultivation of hope: “This kind of hope requires a clear and honest discernment of the current conditions of our world. It does not sugarcoat reality, but it does remain convinced that a better world is possible” (Berila, 176). With this hope, we can then move forward stronger and more inspired.

Strengths and Limitations

Org-as-organism is a powerful metaphor that reminds us that organizations are not just wholes, but are made up of individual moving parts each with its own needs. This metaphor helps us see that personal fulfillment is just as important as the fulfillment of the organization’s goals. We can thus see people as people, and collaborate instead of compete. A student in ORST100 described this metaphor as “The idea that individuals can exist within a larger structure with their own interests and, instead of having them conflict and fall apart, have it function as a way to improve the greater good of the organization.” The metaphor reminds us that organizations do not function in a void. There is an important relationship between an organization and its environment. “Like an organism, an organization will need to find its own niche in the ecosystem around it and cannot simply be cloned from another business model,” another ORST100 student notes.

However, org-as-organism is perhaps a little idealistic. Natural organisms are very efficient, and perhaps function too well to be compared to organizations. We can use the metaphor as an ideal, but not always as a good representation of how an organization will work. Another limitation can come from an over-investment in the importance of the environment. The metaphor could give people a scapegoat: leading them to believe that the external environment is to blame for the issues it is facing, although they may be internally sourced.

This chapter was created by Zoe Wong-VanHaren, Angel Li, Sonya Hadley, and Jocelyn Yale.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Barbara Junisbai for her incredible and loving support in our very large class this semester! Barbara gave us all the push we needed to find our own unique ways of contributing and creating community within our class and for that, we thank her!

We also would like to thank the previous authors of this chapter Sophia Rosse and Jackie Young, for providing a framework which helped us get our ideas off the ground and gave us a starting point to begin our work!

Citations:

Berila, B. (2020). Radiating Feminism: Resilience Practices to Transform Our Inner and Outer Lives (1st ed.). Routledge.

Brown, Adrienne. Emergent Strategy. AK Press, 2017.

DePietro, Andrew. “U.S. Poverty Rate by State in 2021.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 10 Dec. 2021, www.forbes.com/sites/andrewdepietro/2021/11/04/us-poverty-rate-by-state-in-2021/?sh=4f55a3f71b38.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass. First ed., Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Lockwood, Beatrix, and Nicole Lewis. “The Hidden Cost of Incarceration.” The Marshall Project, The Marshall Project, 17 Dec. 2019, www.themarshallproject.org/2019/12/17/the-hidden-cost-of-incarceration.

Morgan, G. (1997). Chapter 3: Nature Intervenes. In Images of organization. London: SAGE.

“Organism.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/organism.

“Ranking: Military Spending by Country 2020.” Statista, 7 May 2021, www.statista.com/statistics/262742/countries-with-the-highest-military-spending/.

SIPRI, www.sipri.org/.

“’The Confess Project’ Aims to Train Barbers to Help with Clients’ Mental Health.” NPR, NPR, 15 Aug. 2020, www.npr.org/2020/08/15/902812017/the-confess-project-aims-to-train-barbers-to-help-with-clients-mental-health.