4 Chapter 4 Lauren Rodriguez

A Chronicle of Occupy Wall Street:

The Revolution of the 99 Percent

“I love being down at Occupy Wall Street. The sincerity, the youth involvement, the desire for better, is palpable and moving. There is true caring, sharing, and refreshingly naive hope.”

— Elayne Boosler, comedienne and writer

I. INTRODUCTION

Capitalism generates a wide range of reactions from Americans —whether or not they approve of it typically depends on whether the system is working for them, but in recent times, it is failing an ever-increasing number of people. It is often said that the United States is in a period of “late-stage capitalism,” meaning that our capitalist economic system has reached a point where the rate of crises, injustices, and inequities is accelerating exponentially.

However one characterizes the state of our economy, there is no discounting the growing antipathy to capitalism that has been simmering below the surface for years, as our system fails an ever-increasing number of people. Nowhere is this more pronounced than among young people: only 51 percent of millennials and Gen Zers view capitalism positively, while 49 percent hold a positive view of socialism (Saad 2019). This is a remarkable shift away from previous generations’ support of capitalism, and it begs the question: how has this discontent with capitalism manifested itself in society at large?

Perhaps the most memorable, generation-defining instance of this discontent bubbling over can be found in 2011’s Occupy Wall Street protests, in which thousands of protestors descended upon New York’s Zuccotti Park and refused to leave until their demands were met. They were, intentionally, a movement without leaders or a defined set of goals — their chief aim was to remedy wealth inequality by removing corporate influence from the government. The protestors occupied the park for months, uniting together under the enduring slogan, “We are the 99 percent.” Their time in the park, which ended only when police descended on them to violently clear them out, provoked a national conversation about the inequities of capitalism.

Occupy Wall Street did not arise in a vacuum. It was the result of widespread disillusionment with the American economy, which was isolating people and leaving them out of any chances to fulfill the ideals of the “American Dream.” These feelings were only compounded by the 2008 financial crisis, where the housing bubble burst, large banks went under, and everyday Americans saw their finances evaporate. As we will see, the aftermath of the 2008 crisis was pivotal to catalyzing the rise of Occupy Wall Street.

To properly understand this social movement, it is necessary to consider sociological frameworks that explain the factors contributing to the movement’s rise and fall. These theoretical perspectives show not only why Occupy Wall Street gained momentum, but also suggest that the conditions of capitalism make it likely that movements similar to Occupy will maintain a recurring presence in American society.

A Weberian and Durkheimian analysis will shed light on the particular reasons for this outpouring of mass anti-capitalist sentiment. From their perspectives, capitalism inherently begets fractured societies that leave individuals feeling isolated and powerless. Weber’s work discusses this at length — he criticizes the “Protestant work ethic,” which created a culture of endless toil while simultaneously stigmatizing leisure. Of particular importance is Weber’s concept of the “iron cage,” which explains how over time, society has become more rationalized and more ruthlessly capitalistic, alienating people from each other until they feel trapped in a metaphorical cage. He puts forth a powerful denunciation of capitalism and its tendency to value the pursuit of profits over individual well-being. Occupy Wall Street bucked many of capitalism’s most destructive facets, from its rigid hierarchies to its cold, unfeeling bureaucracies, in a move that Weber would likely look favorably on.

Durkheim’s discussion of anomie adds onto this analysis by explaining a related consequence of capitalism. Anomie tends to occur most heavily during a time of significant sociopolitical change — individuals feel anomie when the social bonds connecting themselves with their broader community are weakened. It is particularly salient in competitive capitalist societies, where failure to get a “good” job or display symbols of wealth can be the catalysts for anomie. If it goes unaddressed, it can drive people to suicide or other extreme measures. Social movements help to provide an antidote to anomie by creating a sense of community and an opportunity to fight the looming specter of capitalism. In this study, we will explore how Occupy Wall Street helped individuals, especially young people, combat their feelings of anomie or being locked in the iron cage by providing a space for community and anti-capitalist solidarity.

Marxist analysis, particularly conflict theory, will also be used to take a broader institutional perspective as to how the movement arose. How did American institutions fail their people so badly? Why did the protestors feel that radical, even violent action was necessary for their cause? Conflict theory helps to explain why the protesters felt that their only recourse was to stay in the park for months. Under the conflict theory employed by Marx, society is a constant struggle for power between the oppressor and the oppressed. This group of primarily young people, tired of being subjugated by the entrenched power elite, banded together in an effort to no longer be the oppressed. According to Marx, this movement was inevitable under capitalist conditions; Marx and his academic partner Engels saw capitalism as an inherently unstable system characterized by continuous crises that would only compound discontent.

Ultimately, Occupy Wall Street died down without winning significant policy concessions from the power elite. That doesn’t mean it was an abject failure, however. Occupy Wall Street left lasting impacts on national discourse and forced Americans to pay more attention to the income inequality plaguing our nation. It also provided a space for community that both Weber and Durkheim would deem as an important form of anti-capitalist resistance. The founders would likely diverge on the degree to which the movement was successful — while Marx would critique it for not taking bold enough measures to achieve its goals, Weber and Durkheim would celebrate it for changing social norms to focus on wealth inequality and for rebuilding the social ties that capitalism has severed. The movement was flawed, like every social movement is, but its lasting influence on the national conversation is undeniable.

In analyzing the impact of Occupy Wall Street, Manuel Castells’ work is crucial. Castells’ framework of a “project identity,” a collective identity forged by actors seeking to reorder the social structure, helps clarify the goals of the movement and the decisions that shaped it. Further, we can employ Castells’ analysis to understand why it was so successful — the organizers excelled in developing an accessible, consistent message that clearly defined their adversary and goals. As a “project identity,” the work of Occupy Wall Street continues on long after the protestors have dissipated from Zuccotti Park. Its organizers and constituent members are dispersing to new homes to fight for new progressive causes, from the Bernie Sanders campaign to local community organizing and mutual aid efforts. As Castells suggested, they have all committed themselves to moving society forward and advancing socioeconomic equity, making their influence indelible.

Occupy Wall Street may not have been a perfect movement, but it can teach us a great deal about the conditions that inspire mass revolt and explain the rise of future movements. The lessons learned from them provide not only an understanding of what causes social dissent, but also tactics for channeling this discontent into effective movements that create lasting change.

II. CAPITALISM AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS:

WEBERIAN, DURKHEIMIAN, MARXIST, & CASTELLSIAN FRAMEWORKS

Max Weber’s critique of capitalism starts with its initial roots in a Protestant sense of guilt, which has engendered a work-centric society that prioritizes people’s labor over people themselves. In his seminal work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber lays the foundation for an extended critique of the toll capitalism has taken on people, which can be traced back to its very roots in a Protestant sense of “guilt.” Unlike Catholics, Protestants don’t have the opportunity to be regularly forgiven for, and cleansed of, their sins: under Protestant dogma, only God can forgive, and this judgment does not come until the end of a Protestant’s life. This left Protestants, particularly Calvinists, feeling the perpetual, anxiety-inducing need to prove their virtue through hard toil: the rise of Protestantism correspondingly gave rise to a work-centric society in which it was customary and expected to work long hours with few holidays or days of rest. Out of this philosophy, modern capitalism was born.

Weber coined the term “Protestant work ethic” to describe this phenomenon, and the term stuck. In general, this ethic has led to widespread disenchantment with the world and the loss of a sense of joy: Protestants no longer believed in miracles or accounted their prosperity to miracles, instead viewing it as the result of years of hard work. Weber acknowledges that developing capitalism was not Protestants’ intended goal, but that it was nevertheless the result:

While investigating the relationships between the old Protestant ethic and the development of the capitalist spirit […] this should not be taken to mean that we expect to find that one of the founders or representatives of these religious communities in any sense saw as the aim of their life’s work the awakening of […] the ‘capitalist spirit.’ (Weber 2002: 25).

What’s more, Weber goes on to note that some Protestant leaders may be actively opposed to capitalism, suggesting that it was a consequence they never wished for nor foresaw — capitalism was a monster that no one had intended to create.

As Weber explains, it is unsurprising that capitalism leads to a sense of isolation and unhappiness, particularly once it has become entrenched in a society’s way of life. And as society becomes more and more rationalized, discontent under capitalism is only growing. Rationalization is a paradigm that favors reason over emotion or tradition, creating a society governed by immutable rules of logic. A rationalized society is characterized by its impersonal, ruthlessly efficient bureaucracy. In turn, many individuals feel alienated from a society that shows little care for their individual emotions or well-being, causing them to feel locked in an “iron cage.” Weber’s framework of the “iron cage,” which he defines as an “immutable shell in which [an individual] is obliged to live” (Weber 2002: 13), neatly captures the pitfalls of capitalism. The iron cage constrains thoughts and actions within a framework of technorational thoughts and processes. As capitalism maintains its iron grip over people’s lives, forcing them to work long, thankless hours, the number of people locked in their iron cage only grows — and the feeling of being mere cogs in a bureaucratic machine continues to foment.

Indeed, the iron cage is a strikingly similar concept to Emile Durkheim’s concept of anomie, which means a sense of disconnect from society due to weakened social cohesion. The two concepts go hand in hand — being confined to our iron cages can often create a feeling of anomie. Both Durkheim’s discussions of anomic and egoistic suicide are relevant here in understanding the inescapable isolation that capitalism creates; Durkheim explains that “both [anomic and egoistic suicide] spring from society’s insufficient presence in individuals […]” (Durkheim 1951: 258). Anomic suicide is typically catalyzed by social changes that create new, unfamiliar environments for individuals. Egoistic suicide, for its part, arises when an individual feels totally and completely cut off from society, with no recourse and nowhere to turn. In both of these cases, society provides no support network for the struggling individual. The conditions of capitalism can therefore enable either anomic or egoistic suicide.

Those most vulnerable to anomie are typically those left behind by capitalism. Durkheim explains that modern societies are bound together by organic solidarity, where every individual has a specialized role. Organic solidarity is analogous to the functioning of a human body: individual organs all do their specialized job to create a whole greater than the sum of its parts. However, when an individual does not have a role (i.e., a job) in society, they become disconnected from the human body, creating feelings of anomie (Marks 1974). Therefore, the more defective capitalism is and the less able it is to provide every individual with a productive occupation, the higher the frequency of anomie.

Recapturing a sense of community is essential to combatting anomie, dismantling iron cages, and rebuilding the organic solidarity that binds society together. Following both Weberian and Durkheimian analysis, then, it is natural for social movements to eventually rise up as a form of resistance against capitalism’s negative effects. The conditions are there, but it typically takes a catalyzing event to spark a movement.

Marx would take a more radical approach, driven by conflict theory, to the question of how social movements come into being. He and Engels take Weber and Durkheim’s work a step further by positing that revolution is wholly inevitable, and that it is insufficient for people to merely come together in solidarity against capitalism: they must overthrow the system altogether. While Weber and Durkheim do not go so far as to say that capitalism as a system is wholly irredeemable, Marx has no problem doing so. His theoretical framework emphasizes the necessity of revolution over reform, based on the belief that capitalism as a system is broken beyond repair. The ending lines of the Communist Manifesto sum up this philosophy quite clearly: “Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!” (Marx and Engels 1848). The implication here is not that workers should politely and patiently ask the bourgeoisie to grant them rights — rather, Marx and Engels are calling on the proletariat to stage a revolution, a violent one if necessary, to seize their rights.

The resulting paradigm — conflict theory — asserts that revolt by the proletariat is bound to occur eventually. Under conflict theory, society is defined by an oppressed-oppressor relationship. Every member of society is in constant competition for limited power and resources; meanwhile, the ruling class is willing to suppress and impoverish workers in order to hold on to its own power, whether political, social, or economic. In the eyes of Marx and Engels, all forms of power are tools of oppression: “Political power, properly so called, is merely the organized power of one class for oppressing another” (Marx and Engels 1848: 27). Therefore, it is not enough to reform the system “from the inside,” as many may propose, because any form of power under a capitalist system is not only corrupting but is also a tool of oppression. Marx states that the only way to turn the tide is for workers to come together and overthrow the bourgeoisie, establishing a new social order — because not only is capitalism unequal, but it is also highly unstable. Marx’s philosophies lay a strong, albeit militant, roadmap for those who feel subjugated by capitalism.

Although Weber and Marx diverged on some fundamental arguments (e.g., the role of religion), they both critiqued capitalism extensively for its role in prioritizing property over people and thereby making people feel underappreciated or alone in the world. For example, Marx’s concept of “commodity fetishism” echoes that of the “iron cage,” in that both reflect the social isolation and detachment caused by capitalism. Commodity fetishism is essentially the hegemonic belief that an object’s intrinsic value is measured by money and not by the labor that went into making it. The problem with commodity fetishism is that it overlooks the role of people and the value they provide, erasing the actual workers who created the commodity. In doing so, it discounts the importance of interpersonal relationships by instead elevating financial worth as the defining metric of value.

Marx and Engels reach a conclusion echoing that of Weber and Durkheim: capitalism causes alienation from the product of your work, from the activity of your work, from others, and from your own humanity. Commodity fetishism, the iron cage, and anomie are all quite different concepts, but what they share in common is their focus on how capitalism drives people to become socially isolated. Those living under capitalism become increasingly desperate to escape their isolation, and social movements often provide the way out.

Once an individual has chosen to align themself with a particular movement, it then becomes important to examine the nature of the movement itself. Hence, Manuel Castells’ work on social movements forms the next key piece of the puzzle. Castells, a contemporary sociologist, has developed a system of categorizing different kinds of social movements by their “identity.” Under Castells’ framework, there are three major forms of collective identities: legitimizing identity, resistance identity, and project identity.

Legitimizing identities typically belong to mainstream institutions that are seeking to justify and expand their influence in civil society. Resistance identities, in contrast, are held by those going against the grain of society’s dominant cultural mores. Their principles are “different from, or opposed to, those permeating the institutions of society” (Castells 2010: 8), such as white supremacist movements that resist current cultural progress and instead seek to return America to its original roots of racism. Lastly, project identities stand in direct opposition to resistance identities. Castells characterizes project identities as “when social actors, on the basis of whatever cultural materials are available to them, build a new identity that redefines their position in society and, by so doing, seek the transformation of overall social structure” (Castells 2010: 8). These are often referred to as “progressive” social movements.

Regardless of their type, all movements share a few salient characteristics: an identity, an adversary, and a social goal. These are all identified by the movement itself and are key in shaping a movement’s tactics, popular perception, and more. “Identity” refers to the people on behalf of whom a movement purports to speak, whereas “adversary” refers to the movement’s “principal enemy” (Castells 2010:74). The social goal is the “movement’s vision of the kind of social order, or social organization, it would wish to attain in the historical horizon of its collective action” (Castells 2010:74). This holds important implications for the movement’s propensity to succeed, because a movement has the responsibility to define their own identity, adversary, and goal, then disseminate that message to the public. As Castells says, social movements “are what they say they are” (Castells 2010:73), and it is incumbent on the organizers to make their self-identification clear. Stronger clarity of message makes a movement better-equipped to attain success.

Now, with all of those frameworks in mind, we turn to the case of Occupy Wall Street and look at the factors sparking the growth of the movement. It is first important to station the protest within its specific moment in history and contextualize its rise with data.

III. THE CASE: OCCUPY WALL STREET

2011 came at an inflection point in American history. The country’s first Black president, Barack Obama, had just taken office two years prior, and had inherited a financial crisis more dire than any recession since the Great Depression. Finally, the media wrote, President Obama was leading an economic recovery characterized by the liberal usage of bailouts and other forms of government spending to get the economy back on track. But this did not capture the full picture of the 2011 zeitgeist. Many young people felt left behind from what was purportedly an era of progress, struggling under the weight of skyrocketing costs and debts. They shared a collective sense of alienation from capitalism and the perception that the economic system in the United States was not working for them — one that can be seen in statistics and polls.

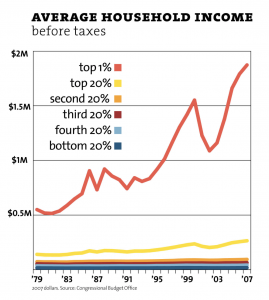

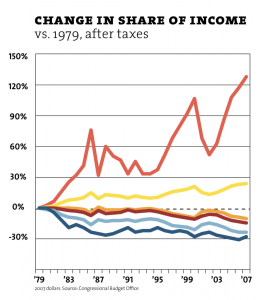

The conditions that sparked Occupy Wall Street were quite dire. A historically-high number of people were facing the threat of foreclosures after the housing bubble burst, unemployment was far higher than its typical numbers at 9.1 percent, and student loan debt was only continuing to pile up. As the lower and middle classes struggled, elites were doing better than ever. The economy was rebounding from the financial crisis, but economic growth had been lopsided — a UC Berkeley economist estimated that “between 2009 and 2012, the top 1 percent captured 95 percent of total economic growth” (Sommeiller and Price 2014). Out of every state, New York had the largest gap between the top 1 percent and the bottom 99 percent; the top 1 percent made about 40 times more than the bottom 99 percent. This helps to explain why the protests arose in New York specifically. Figures 1 and 2 (Gilson and Perot 2011) provide more evidence for the mass increases in income inequality that plagued the 2011 economy.

Figure 1 Figure 2

And, according to the Brookings Institution, corporate executives were making almost 300 times the salary of the average worker (Sawhill 2011). Wealth inequality was just as much of a problem as income inequality: the top 1 percent made about one fifth of the nation’s total income but held over a third of the nation’s wealth. Data from this time period allows us to reach a clear conclusion: while many in the media and popular culture had moved on from the financial crisis, its ramifications were still very much real, and discontent was bubbling under the surface.

Data can also help explain who was out there protesting and, by extension, show us which segments of society experienced the most dissatisfaction with capitalism. A compilation of statistics from The Week found that 64 percent of movement members were under the age of 35, indicating a movement composition that skewed young. About 27 percent were still students; meanwhile, 15 percent were unemployed, and 13 percent identified as part-time employed or “underemployed.” There was widespread consensus — 98 percent — about willingness to engage in civil disobedience to achieve their desired goals, while about one-third (31 percent) of protestors said that they would support violence if it helped them meet their ends. Another striking statistic: while 74 percent of the protestors who voted in 2008 cast their ballot for President Obama, 51 percent reported that they no longer approved of President Obama. Although he had run on an ambitious platform defined by the slogans “Yes We Can” and “Change we can believe in,” many of his supporters appeared to be second-guessing whether change truly was on the horizon.

These statistics indicate that Occupy Wall Street’s key bloc was disillusioned young people who had put their faith in President Obama but now felt left behind by his administration and by the system as a whole. Fully 33 percent of them were not in a job that utilized their full potential, causing them to feel stagnant and dissatisfied. And more than ever before were burdened down by student loans, which grew 511 percent between 1999 and 2011 (Indiviglio 2011). Economic uncertainty ran rampant. But when we take a closer look at the human element of the protest, which cannot be captured by empirical data, we find that people were not just looking to fight capitalism from an economic standpoint — they were also looking for ways to recapture the emotional connections and social ties that capitalism had taken from them.

IV. ANALYSIS: FINDING SUCCESS IN SOLIDARITY

The protestors stayed in the park for months as Occupy movements sprang up across the country. Their demands were sweeping; they called for a myriad of policies, some vague and others more specific, that would combat corporatism and remedy income inequality (Hoffman 2011). But in the end, they were cleared out of the park in November, having won very few (if any) major policy concessions. This begs the question: to what degree can Occupy Wall Street be considered a success?

It first must be said that defining a movement’s success by its policy wins is a narrow definition that ignores many of its key facets. Often, change is not immediate, particularly because policymaking in America is defined by frustratingly slow incrementalism, slowed down by intense partisan gridlock. It would be a mistake to dismiss Occupy Wall Street as a failure solely due to the lack of policy produced in 2011. We must instead look at its long-term influence and the ways in which it impacted the national conversation.

For one, Occupy Wall Street shifted the Overton Window to the left and ushered in a greater focus on economic inequality. The Overton Window, in short, is the range of policy options deemed acceptable by the public at the current moment in time. It encompasses the span of policies receiving media attention and a place on the policy agenda; political activists’ goal is to expand the window or shift it in their preferred direction (Astor 2019). Now more than ever, we are having serious conversations about cancelling student debt, raising the minimum wage significantly, curtailing corporate influence over political decisions, and more.

Similarly, under John Kingdon’s “windows of opportunity” model, Occupy Wall Street created new policy windows that legitimized progressive economic policies and placed them on the legislative agenda. According to Kingdon, policies are implemented when a “window of opportunity” becomes available for that particular policy; windows are created when a policy stream, problem stream, and politics stream are all present (see, e.g., Figueroa et al. 2018). Occupy Wall Street was particularly influential in the politics stream, which refers to the presence of motivation to solve a problem — the Occupy movement helped generate a significant degree of motivation, uniting people around the shared desire to address inequality.

Moreover, we have seen the rise of populist leftist politicians such as Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who have won millions of fans by enthusiastically championing the very same policies for which Occupy Wall Street advocated. Indeed, Senator Sanders’ staff overlaps significantly with people who participated in, or wrote favorably about, the Occupy movement. Heather Gautney, for example, is a sociology professor at Fordham University who covered the movement extensively, commending the protesters for their tenacity and disseminating their message to a wider audience (see, e.g., Gautney 2013). Now, Ms. Gautney is a top advisor to Senator Sanders, both on his presidential campaigns and in his Senate office, serving as a senior policy advisor as well as an executive director of Our Revolution, a Sanders political action committee. Other presidential candidates in 2020, most notably Senator Elizabeth Warren, adopted the rhetoric of Occupy Wall Street, promising to hold billionaires accountable for their actions. This shifting discourse is emblematic of the Occupy movement’s impact.

The rise of populism is true even on the right wing of American politics: Donald Trump ran for president in 2016 on an unapologetically populist message, promising to bring jobs back and to fight the “establishment.” Our political climate has shifted, with an increased recognition of the need to appeal to those who have lost faith in our institutions — and Occupy Wall Street has played an undeniable (and likely larger than people may think) role in this realignment.

Applying a Castellsian framework, the movement can similarly be deemed a success. The Occupy organizers created a collective identity that was unambiguously a “project identity,” leaving little doubt about where the movement stood or what its ultimate goals were. To be sure, from a public policy standpoint, the policy aims were often muddled, and different Occupy chapters chose to pursue a variety of priorities. But the overarching message remained unwaveringly consistent throughout the entirety of the movement: the power and wealth of the 1 percent must be diminished in order to create a more just social order. Heather Gautney explains in a Washington Post article that the Occupy movement is organized “according to a simple yet powerful point of unity: ‘The one thing we all have in common is that we are the 99% that will no longer tolerate the greed and corruption of the 1 percent’” (Gautney 2011). This fundamental, unifying message was the movement’s driving force, clearly defining the “social goal” and leaving little doubt that Occupy Wall Street had organized itself around a progressive “project identity” seeking to transform society.

Notably, the message articulates not only a goal and identity but also an adversary: for the Occupy movement, the adversary was the 1 percent, whose “greed and corruption” had become intolerable. This one succinct “point of unity” exhibits Castells’ three key characteristics of a social movement, and therefore indicates that the organizers were successful in making their goals clear and unequivocal. Occupy Wall Street’s ability to define exactly why it is here and place itself in firm opposition to another collective — the 1 percent — ensures the longevity of its message. Nearly ten years later, the term “1 percent” is still a fixture of any economic discourse, and everyone remembers the movement vividly, marking a major success — long past the protestors dispersed from the park, the “project identity” of their movement maintains its presence in society.

Of equal importance is the opportunities that the Occupy movement provided for solidarity, helping to rebuild social ties that capitalism had broken. Histories of Occupy Wall Street suggest that it served as not only a protest area but also as a gathering space where individuals could come together in community and provide mutual aid. Because the protestors physically gathered in Zuccotti Park and remained for many months, it is natural that they began to develop strong ties with each other. In an oral history of Occupy Wall Street published by Vanity Fair, one member admits that by November, “The movement was becoming about taking care of people in a park rather than holding Wall Street accountable” (Lalinde et al. 2012). Perhaps the member meant to characterize this as a failure of the movement, but it must be acknowledged that “taking care of people in a park” is a radical act of resistance in and of itself. Capitalism encourages individualism and incentivizes people to compete with each other to no end. The simple act of sacrificing one’s own resources to help another is a form of collaborative activism that disobeys the unwritten rules of capitalism; in turn, it rebuilds collective consciousness and helps individuals break out of the “iron cage.”

Also of note is the horizontally-organized, deliberately leaderless structure of Occupy Wall Street. This provided a welcome contrast to the rationalized, vertically-organized bureaucracy that Weber wrote about. Heather Gautney explained in a Washington Post article that the Occupy movement is intentionally without leaders or concrete demands, and that their decision-making process eschews top-down directives in favor of deliberative democracy. Gautney further noted that this organization is meant to “avoid replicating the authoritarian structures of the institutions [the protestors] are opposing” (Gautney 2011), a profoundly important idea. The protestors recognized that to liberate themselves from the oppression of the iron cage, they needed to take a radically different approach to organizing. Hierarchical structures obstruct the formation of community ties by instead privileging some people’s viewpoints over others and causing those at the bottom rung to feel useless, as Weber detailed. By bucking this traditional organizational format, Occupy Wall Street achieved a more genuine sense of community than one would expect to see under a rationalized, bureaucratic state.

In some ways, the movement functioned almost as a religious group, which is fitting given Durkheim’s theories on how organized religion can serve as an important bulwark against anomie. Religion, according to Durkheim, helps give people a sense of direction and prevents them from feeling alone or adrift. From Durkheim’s point of view, “religion is and must and can only be social” (Wallis 1914), meaning that by its definition, religion serves a social role. But in our increasingly rationalized society, as Weber notes, people are losing ties to religion, creating new social gaps. Occupy Wall Street helped fill this void and give people the reassurance that they are not alone. A group of people with a similar set of core values, gathered together in a shared space to both change the world and take care of each other — that resembles religion quite significantly.

Ruth Wallace and Shirley Hartley corroborate this analysis with their theory that “Durkheim viewed friendship as a functional alternative to religion for individuals in modern society” (Hartley and Wallace 1998:93), arguing that friendships can recreate social bonds and provide a sense of meaning that is too often absent from modern society. They write that friendships create “a sense of extending beyond oneself and feeling a sense of unity with others” (Hartley and Wallace 1998:95), which perfectly encapsulates one of Occupy Wall Street’s chief achievements. Hence, from the Durkheimian perspective, Occupy Wall Street’s function became similar to that of a religion, providing people a respite from capitalism’s ruthless individualism and combatting anomie. This ultimately strengthens society’s common consciousness, helping the protestors feel that there is finally a place where they belong.

The protestors’ ability to form new social connections and bonds constitutes a resounding success on their part. As Weber and Durkheim clearly show, many of the worst consequences of capitalism are not only economic but also social, and the alienation brought on by capitalism is deeply dangerous. President Obama ran on a message of hope and change, giving the many young people who voted for him a renewed faith in America. The historic nature of Obama’s presidency made people think that the nation was headed on a new path, one that would open up more opportunities and usher in an era of hope.

As the statistics shown in Part II indicate, the systemic change that many expected under President Obama did not materialize. This only compounds the excessive hopes and false promises that Durkheim says are common under capitalism. In Durkheim’s view, capitalism makes people believe that they can all be wealthy; however, this is not the case, and the high expectations people hold for themselves make it all the more likely that they will be disappointed. If they fail, it becomes a judgment on the individual alone, and they are said to have no one to blame but themselves. Weber touched on this phenomenon as well, believing that the Protestant reformation transformed a communal society into an individualistic one that emphasized the personal responsibility to achieve economic success. All of this is only heightened by the nature of 2011-era America, where people buoyed by the optimistic rhetoric of President Obama’s 2008 campaign hoped to enjoy an age of prosperity.

Occupy Wall Street offered a salve to this deep disillusionment. People — and especially young people— came together realizing that they were not alone in feeling this way, and that they were not unique failures but that there were thousands with whom they shared an experience. The protests further showed that the failure to achieve financial success does not necessarily mean an individual has failed — often, it means that the system has failed the individual. Occupy Wall Street helped its members realize that they were not inherently inadequate, and that they should channel their disappointment not inwardly but instead towards the institutions that were ostensibly built to serve them. In this way, the movement helped to alleviate anomie among its participants. Weber would have applauded the protestors’ ability to recapture a sense of joy in a capitalist system designed to deprioritize such joy. One article from the time chronicles this emotional journey, writing that “the human connections [the protestors] made injected them with hope, filled life voids, and even erased boredom” (Lazar 2011). This sense of deep connection and meaning that Occupy Wall Street created among its constituent members is remarkably important. It called into question the hegemonic narrative that individuals’ primary purpose should be generating capital, and helped to free the community from their iron cages of isolation. I believe that Weber and Durkheim would be proud.

Marx would likely have a different answer than Weber and Durkheim: he would not be satisfied with the movement, nor would he consider it a success. According to Marx, nothing short of revolution is adequate for addressing the underlying causes of inequality. Any Marx-approved social movement must work to dismantle systems of oppression altogether; if it fails to do so, Marx would consider it insufficient. Marx and Engels believed strongly that successful movements must recognize that capitalist institutions are beyond repair or reform, and they therefore must operate outside of these structures of power entirely. They would likely look at the statistic that 31 percent were willing to use violent means to achieve their desired ends and call that a missed opportunity — if over 90 percent were comfortable breaking laws and about a third were ready to deploy violent tactics, Marx would expect them to overthrow the system in its entirety. But even with that being said, Marx likely would have cheered the protestors for refusing to submit to the system quietly. They helped weaken the grip of commodity fetishism and other damaging attitudes towards labor and capital. Marx may not have been a reformist himself, but there is nevertheless something to be said for the gradual progress that Occupy Wall Street helped usher in.

While we can clearly trace the factors that catalyzed the ascent of the movement — a ubiquitous sense of disappointment with one’s economic and social conditions — there is no unequivocal answer to whether or not Occupy Wall Street was a success. It is a complicated question that yields different answers — which are never black-and-white — depending on which theoretical framework is applied. The work of Castells, Weber, and Durkheim points to the movement being a success; meanwhile, Marx would be heavily critical of the movement, and many policy analysts would likely be split on the ultimate effectiveness of Occupy Wall Street. As with many social phenomena, it seems that the answer lies somewhere in the middle. The Occupy movement may not have achieved achieve the radical, immediate change many of its members hoped for, but it did impact our policy agenda, alter the national conversation, and normalize community-based models of care, all impressive accomplishments in their own right.

V. CONCLUSION

Occupy Wall Street did not mark the end of protests in the United States by any means. Social movements have continued to rise up, particularly as a response to the divisive Trumpian era, but the real test is whether or not they have staying power.

Movements such as #MeToo, March for Our Lives, and Black Lives Matter have all achieved national prominence, but with the 24-hour news cycle, it’s difficult to keep movements in the limelight long enough for them to gain a place on policymakers’ agenda. Interestingly, although the movements protest against a variety of social ills, many of their grievances can be traced back to the inequities of capitalism. #MeToo calls out executives who valued profits over people and protected sexual abusers like Harvey Weinstein because of his ability to rake in money. March for Our Lives exposes the cowardice of politicians who are too afraid to speak up against the NRA gun lobbyists for fear of losing campaign donations. And Black Lives Matter fights against a state that has denied Black people the resources and reparations they need to close the racial wealth gap. All of these movements, and more, underscore just how prescient Weber, Durkheim, and Marx were in their critiques of capitalism and their predictions that people would become deeply unhappy under this system.

Future studies in this area may examine the similarities and differences between those movements, and dive more deeply into what we can learn from each one. There are still important lingering questions about Occupy Wall Street, such as the issue of whether it was appropriately representative of the 99 percent or whether it instead captured only a sliver of young, predominantly white, city-dwellers who were not attuned to the entirety of the 99 percent. For example, Black scholar Emahunn Raheem Ali Campbell, who participated in the protests wrote a cogent critique of the movement — he noted that white organizers had not sufficiently acknowledged their privilege or created spaces to discuss race, that the very term “Occupy” can carry off-putting imperialist connotations, and that issues such as student loan debt alienated the Black community, many of whom do not have the opportunity to even attend college due to disparities in access to education (Campbell 2011). It is also worth examining the rise of populist politicians, mentioned earlier, and examining just how closely their ascent can be attributed to the influence of Occupy Wall Street. There is no question that the case of Occupy Wall Street provides sociologists with a wealth of research questions to explore.

Weber, Durkheim, and Marx show us that as capitalism continues its dominance over the United States, the disillusionment it engenders will not disappear overnight. People will continue to feel left behind and frustrated with the ruling class’s focus on preserving the status quo above all else — and invariably, these feelings of frustration will continue to find a home in social movements. We can continue to look forward to a better future, where people no longer need to mobilize against an unjust social order. At the same time, we must take a clear-eyed, realistic view of America and acknowledge that capitalism is here to stay for the foreseeable future. The question, then, becomes how we can best unite in solidarity and practice productive acts of resistance. And as someone personally interested in social movements, both as an active participant and as an academic observer, I believe that every movement can learn lessons from the past. It can take the best of previous movements, discard the worst, and build strong coalitions that effect tangible change. Occupy Wall Street’s meteoric rise and its subsequent redefinition of what constitutes a movement’s “success” provides a useful roadmap for future social movements.

Bibliography

Anon. 2011. “The Demographics of Occupy Wall Street: By the Numbers.” The Week. Retrieved November 14, 2020 (https://theweek.com/articles/480857/demographics-occupy-wall-street-by-numbers).

Astor, Maggie. 2019. “How the Politically Unthinkable Can Become Mainstream.” New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2020 (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/26/us/politics/overton-window-democrats.html).

Campbell, Emahunn Raheem Ali. 2011. “A Critique of the Occupy Movement from a Black Occupier.” The Black Scholar 41(4):42–51.

Castells, Manuel. 2010. The Power of Identity (The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture) . 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Durkheim, Emile. 1951. Suicide, a Study in Sociology. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

Engels, Friedrich, and Marx, Karl. 1848. The Communist Manifesto.

Figueroa, Chantal et al. 2018. “A Window of Opportunity: Visions and Strategies for Behavioral Health Policy Innovation.” Ethnicity & Disease 28(Supp 2):407–16.

Gautney, Heather. 2013. “Occupy Wall Street Movement.” The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

Gautney, Heather. 2011. “What Is Occupy Wall Street? The History of Leaderless Movements.” The Washington Post. Retrieved November 30, 2020 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/on-leadership/what-is-occupy-wall-street-the-history-of-leaderless-movements/2011/10/10/gIQAwkFjaL_story.html).

Gilson, Dave and Carolyn Perot. 2011. “It’s the Inequality, Stupid.” Mother Jones. Retrieved November 23, 2020 (https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2011/02/income-inequality-in-america-chart-graph/).

Hoffman, Meredith. 2011. “Protesters Debate What Demands, If Any, to Make.” Retrieved November 23, 2020 (https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/17/nyregion/occupy-wall-street-trying-to-settle-on-demands.html).

Indiviglio, Daniel. 2011. “Chart of the Day: Student Loans Have Grown 511% Since 1999.” The Atlantic. Retrieved November 16, 2020 (https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/08/chart-of-the-day-student-loans-have-grown-511-since-1999/243821/).

Lalinde, Jaime, Rebecca Sacks, Mark Giuducci, and Elizabeth Nicholas Max Chafkin . 2012. “An Oral History of Occupy Wall Street.” Vanity Fair. Retrieved November 14, 2020 (https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2012/02/occupy-wall-street-201202).

Lazar, Louie. 2012. “Occupy Wall Street Protesters Find Happiness and Meaning in Zuccotti Park.” Retrieved October 1, 2011 (https://pavementpieces.com/occupy-wall-street-protesters-find-happiness-and-meaning-in-zuccotti-park/).

Marks, Stephen R. 1974. “Durkheim’s Theory of Anomie.” American Journal of Sociology 80(2):329–63.

Saad, Lydia. 2019. “Socialism as Popular as Capitalism Among Young Adults in U.S.” Retrieved November 30, 2020 (https://news.gallup.com/poll/268766/socialism-popular-capitalism-among-young-adults.aspx).

Sawhill, Isabel V. 2011. “2011: The Year That Income Inequality Captured the Public’s Attention.” Brookings Institution. Retrieved November 14, 2020 (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2011/12/19/2011-the-year-that-income-inequality-captured-the-publics-attention/).

Sommeiller, Estelle and Mark Price. 2014. “The Increasingly Unequal States of America: Income Inequality by State, 1917 to 2011.” Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved November 15, 2020 (https://www.epi.org/publication/unequal-states/).

Wallace, Ruth A. and Shirley F. Hartley. 1998. “Religious Elements in Friendship: Durkheimian Theory in an Empirical Context.” Durkheimian Sociology: Cultural Studies 93–106.

Wallis, Wilson Dallam. 1914. “Durkheim’s View of Religion.” Journal of Religious Psychology, including its Anthropological and Sociological Aspects 7(2):252-267.

Weber, Max. 2002. The Protestant Work Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism. New York, NY: Penguin Books.