3 Chapter 3 Elise Kuechle

Image Source: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Classical Sociology and Nontraditional Families: Unpacking the Stigma of Single Motherhood

Elise Kuechle

Pomona College

Word Count: 5159

Introduction

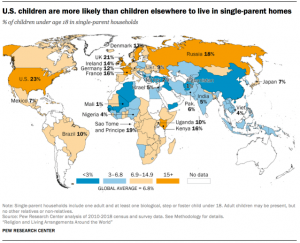

In 2015, a Pew Research Center study reported that Americans were significantly more likely to indicate a negative opinion of single mothers raising children than any other social trend (Pew Research Center 2018). Specifically, 66% of respondents identified the view that single mothers raising children are bad for society (Pew Research Center 2018). This overwhelming majority of opinion crosses lines of gender, race, religion, and political party, and indicates a deeply-held prejudice against single motherhood. It is important, therefore, to ask why single mothers are so largely discriminated against, especially as rates of single motherhood, and single parenthood in general, historically continue to increase and currently stand at an all-time high (U.S. Census Bureau 2016). Specifically, the United States has the highest rate of children living in single-parent homes compared to any country in the world (Pew Research Center 2019). This issue is clearly connected to many areas of social life, through topics such as gender, race, class, and power. One relevant way to understand why single motherhood may be so stigmatized along these lines is to look at the works of classical sociologists, whose study of society, capitalism, and family structure offer one way of framing the prejudice against and judgement of single mothers.

Several founders are specifically useful for understanding this phenomenon. Classical sociologist Friedrich Engels offers a detailed analysis of family life, relating the historical construction of family structure to modern modes of capitalism and property. Scholar Charlotte Perkins-Gilman continues along these themes, questioning the role of the woman in family, motherhood and society. These ideas are obviously important to understand when analyzing family structure, especially when focusing on topics that specifically impact women as mothers. Max Weber’s work adds an interesting perspective to these concepts, with particular emphasis on social stratification and the relationship between class, status, and party. Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony is a central component of explaining why the negative opinion of single mothers remains so prevalent, and allows for inter-class analysis that creates an essential frame for this issue. These theories allow for a more macro lens of exploration, extrapolating the role of the single mother into the broader context of community and society, and providing a potential explanation for the shame attached to single motherhood. Finally, the more contemporary works of Erving Goffman provide an even further analysis of the causes behind stigma for these types of families, offering frameworks for studying deviance and its consequences.

Overall, by examining the works of these sociological founders and more, it becomes possible to understand why single motherhood is so overwhelmingly disapproved of in American society. It is important to understand the many possible answers to this question so that the marginalization faced by this community can be lessened on a personal, community, and policy level. This paper aims to create space for this knowledge within the academic field of sociology, and serves to bring greater equity and justice to single mothers, a population often underrepresented in academia.

Theoretical Grounding

The work of Friedrich Engels in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State provides a strong theory for the history of normative family relations, touching on themes such as gender and capitalism to explain the structure and function of family in society. Engels’ theory traces the roots of patriarchal family structure to the shift from “savagery” to “barbarism,” in which domesticated animals and crops allowed for the greater accumulation of wealth (Engels 2004:11). As a result, women also began to take on a different role as demand for human labor increased and so a woman’s reproductive potential came to the forefront of her purpose (Engels 2004:11). In this way, society shifted from matrilineal to patriarchal, and a woman’s main role became reproductive. With this increased emphasis on property and the accumulation of wealth, the concepts of succession and the transfer of property gave rise to the idea of legitimate paternity and with it, monogamy (Engels 2004:11). Monogamous sexual relationships resigned women to the ultimate power of men, as it was necessary to guarantee the faithfulness of the wife and therefore the legitimate succession of the child (Engels 2004:70). Deviation from this norm has been punishable to different degrees at different points throughout history and society, but has led at times to extreme responses such as the murder of women by their (Engels 2004:70).

With the goal of preserving inheritance always at the forefront of any marriage arrangement, family structure becomes inherently trapped in a capitalistic framework. As Marx and Engels (2017) suggest in one of their most central ideas, capitalism is inherently unstable, and by tying the family unit to capitalism so strongly, the family therefore becomes unavoidably unstable as well. Engels argues that this instability will lead to a breakdown of morals and an increase in sexual immorality and prostitution, two structures which stand in opposition to monogamous marriage (82). There is a difference, however, between the experience of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat in the marital state. According to Engels, since the proletariat owns no property and can accumulate little wealth, marriages are not based on the secure transfer of property but on “sex love,” (78). These marriages are still monogamy-based, but this arrangement is necessitated by passionate love and physical attraction, rather than an economic bond (Engels 2004:78). Although this thinking is logical in many senses, it fails to account for the societal bonds that the expectation of monogamy created for both the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and similarly overlooks other causes for prioritizing monogamy, such as the emotional, religious, and social. Overall, Engel’s analysis of the family offers a crucial framework for understanding the family under capitalism, and gives context to implications of single motherhood in society.

Feminist theorist Simone de Beauvoir offers a critique of Engel’s ideas in her work The Second Sex. She rejects his claim that women’s oppression began as a result of the emergence of private property, as she believed his argument was unsupported (de Beauvoir 2010:64). She offers her own theory for the historical subordination of women, linked much more strongly to reproduction. De Beauvoir suggests that the reason for the oppression of women has largely to do with their participation in production and lack of reproductive freedom (139). This thinking rejects Engel’s theory of inheritance-based monogamy and instead centers a new theory for a family structure that subordinates women around their reproductive history. Both scholars make important points that intersect with the histories of women’s roles and their economic implications, and it is possible to use both points of view to more fully understand the topic of family structure and the discrimination against women.

Although writing before de Beauvoir, American sociologist and writer Charlotte Perkins-Gilman furthered Engel’s contributions to the study of family structure, taking a critical lens to the economic situation of women in relation to men. Perkins-Gilman argues that women are deeply reliant upon men economically, dependent on the male “race” for food and other material goods necessary for survival. Perkins-Gilman (1898) writes, “the economic status of the human female is relative to the sex-relation,” further strengthening the idea that a woman’s economic standing and power is inherently connected to her sexual and marital status. This concept suggests another interpretation of the function of the patriarchal family structure in society, one that equates economic security with reproductive accomplishment.

Perkins-Gilman also writes on motherhood, questioning the societal emphasis that is placed on a woman’s reproductive and child-rearing capacities. She states:

Such a condition, did it exist, would of course excuse and justify the pitiful development of the human female, and her support by the male. Is this the condition of human motherhood? Does the human mother, by her motherhood, thereby lose control of brain and body, lose power and skill and desire for any other work? Do we see before us the human race, with all its females segregated entirely to the uses of motherhood, consecrated, set apart, specially developed, spending every power of their nature on the service of their children? (Perkins-Gilman 1898)

In this quotation, Perkins-Gilman uses a nearly sarcastic tone to demonstrate her skepticism of womens’ “pitiful development.” She suggests the all-consuming role of motherhood as the chief cause for this inequality, calling into question its ability to render mothers powerless and unambitious. Importantly, this concept also points to the isolation of mothers within their roles, devoted and committed as they must be to the survival of their child. In this way, Perkins-Gilman, like de Beauvoir, locates the site of women’s oppression within reproduction, and questions the extreme emphasis that is placed on the totality of this role for the purpose of women in society.

The theories of Engels, de Beauvoir, and Perkins-Gilman all offer useful modes of understanding regarding the specific topics of family structure, gender, and motherhood. It is important, however, to draw on a more macro lens as well to understand the greater causes of stigma around single mothers raising children, and the reasons why this subgroup encounters so much social marginalization. Max Weber’s theories of stratification are a strong place to begin this investigation, as they provide an in-depth examination of the power structure within communities, and the ways in which this power becomes hierarchical.

Weber states that the greatest determinations of power within a community is derived from three things: “class, status groups, and party,” (Weber 2009:1). He defines class in economic terms, stating:

We may speak of a “class” when (1) a number of people have in common a specific causal component of their life chances, in so far as (2) this component is represented exclusively-by -economic- interests in the possession of goods and opportunities for income, and (3) is represented under the conditions of the commodity or labor markets. (Weber 2009:1)

In this way, a person’s class denotes their economic standing within a community, although it is important to note that classes themselves do not constitute communities independently (Weber 2009:1). The term “class,” when used in this way, is helpful for understanding economic conditions as they relate to the theories of family and women’s oppression written by Engels, de Beauvoir, and Perkins-Gilman. When examining Weber’s concept of class through the lens of these classical theorists, it is possible to see that a woman’s dependence on the male sex directly impacts her class status, and her ability to survive independently as a woman and mother. Weber discusses status groups distinctly from class, designating status as a mode of forming community, although a relatively undefined one (Weber 2009:3). These status groupings are based on social honor and prestige, unconnected to wealth or property (Weber 2009:3). Finally, the concept of party touches on a group focused on collective action towards the achievement of a goal, denoting political power and group influence (Weber 2009:6). All of these definitions are useful for understanding the ways in which power flows throughout a group and provides an important framework for the exploration of why single mothers are a generally disadvantaged social community.

To further question the widespread disapproval of single motherhood, contemporary sociologist Erving Goffman provides the sociological concept of stigma that offers clues to why this type of parenting is ascribed such a shameful status. Specifically, his work on deviance provides an excellent template for considering the ways in which single motherhood may pose a threat to social order. According to Goffman, deviation occurs when there is a group of social norms set forth, and an individual or group of individuals does not adhere to these rules and agreements (Goffman 1963:140-141). There are multiple types of deviance, such as “disaffiliates,” individuals who “voluntarily and openly” reject their prescribed role in the social order, specifically connected to societal institutions such as family structure, role division between genders, and economic earning (Goffman 1963:143). Social deviation is frustrating to the goal and advancement of society. As Goffman writes of the types of social deviants described, “They are perceived as failing to use available opportunity for advancement in the various approved runways of society; they show open disrespect for their betters; they lack piety; they represent failures in the motivational schemes of society,” (Goffman 1963:143-144). From the outside, single mothers may appear to reject the traditional ideal of a two-parent household, therefore their existence may be perceived as deviance along this definition. Goffman’s thinking in this quotation provides an interesting theory for why this difference is perceived so negatively by society and how single motherhood became stigmatized. By using Goffman’s frameworks of deviance and previous understandings of family structure, gender roles, motherhood, and power explored by other sociological founders, it becomes possible to explain how single mothers are viewed by society and analyze their negative experiences and treatments in a significant way.

One way to understand why the stigma around single motherhood remains so prevalent despite the U.S.’s high rates of single-parent households is through the works of Antonio Gramsci, whose work on hegemony offers the framework for understanding how popular opinion maintains control over the masses. Specifically, Gramsci defines hegemonic culture as the proliferation of ruling class ideas and values to become ubiquitous guidelines for all people, regardless of their class standing (1992). In this way, the working class aligns their ideals with that of the bourgeoisie in such a manner that their own well-being becomes tied to a status quo that was not created by them (Gramsci 1992). This type of hegemony is perpetuated through institutions, popular culture, education, and religion, and is encoded both explicitly and implicitly in everyday life. Gramsci’s definition of hegemony is one explanation for why monogamy, a value created by the ruling class to protect lines of succession, came to be held similarly by the proletariat, despite vast differences in lived experience of family structure.

The Investigation

The United States contains the highest rate of children living in single-parent homes than any other country in the world: 23% compared to a global average of 6.8% (Pew Research Center 2019). This is likely because of the U.S.’s high Christian population, as Christian families are more frequently headed by a single parent than any other religious group (Pew Research Center 2019). A variety of issues pose obstacles to single mothers, including society’s negative perception of single motherhood, but extending to cycles of abuse and poverty, and struggles for equal opportunity in education and career (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:6). The most overwhelming cause of social judgement towards single mothers is the perception that struggling parents in this situation have created their own difficult circumstances, through “their own neglect, moral turpitude, lack of drive, and, ultimately, failure to appreciate their obligations as citizens,” (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:10). While this demonstrates the basis for the stigma around single motherhood, these perspectives do not take into account the many economic, social, and policy-level factors that contribute to the systematic marginalization of single mothers.

Figure 1. Likelihood of children living in single-parent households by country

For single mothers, economic hardship often arises from difficulties balancing childcare, work hours, and welfare programs. 27% of single-parent led families live in poverty, compared to 16% of married or cohabiting families, and female single parents are twice as likely as married mothers to be in financial crisis, despite being twice as likely to be employed full-time as married women (Pew Research Center 2018, Brown and Moran 1997:21). Single mothers are more likely to experience financial crises than single fathers, as a result of pay inequality and job insecurity related to childbearing and sexism (Lu et al. 2019). Because of the multiple roles single mothers must assume for their children as caretaker, sole breadwinner, mother, and father, economic self-sufficiency is difficult to achieve because of the lack of viable options for training and education (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:11). 63% of mothers who are the sole breadwinners for their families are single women, with a median income of approximately $23,000 per year (Pew Research Center 2013). Inequality in education is one of the leading causes of pervasive poverty for single mother-led households, demonstrated by the fact that 50% of low-income women who gave birth while unmarried had not yet attained a high school degree at the time of their child’s birth (Edin and Kefalas 2011:2). One third of the same group of low-income single mothers reported no work history for one year, reinforcing the link between educational attainment and employment prospects (Edin and Kefalas 2011:2). However, efforts to promote educational attainment for single mothers and their children have shown promising results for closing this economic gap (Western, Bloome, and Percheski 2008:903). All of these factors create a cycle of poverty for single mothers, leading to a necessary dependence on social programs, and unequal access to housing, education, and healthcare.

Abuse is another common theme in the lives of single mothers (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:10). Many single mothers are themselves victims of abuse, vulnerable to exploitation and with little social safety net and support for leaving these unhealthy situations. Intimate partner abuse and child sexual abuse are two of the most prevalent forms of such trauma, which contributes not only to the negative perception of single motherhood, but also to the continued oppression of single women raising children who are survivors of abuse (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:10). Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that women who are survivors of abuse are much less likely to be or remain married, and overall less likely to maintain long-term romantic and sexual relationships (Cherlin et al. 2004:768). Relatedly, the risk of depression for single mothers is double that of married mothers, as they are more likely than other parent groups to experience “humiliating or entrapping severe life events,” (Brown and Moran 1997:21). These include abuse, mental health crises, and other extreme situations which can cause and spread trauma. Overall, this pervasive cycle contributes to the continued oppression of single mothers, exacerbating other difficult factors which trap single mothers and their children in negative patterns.

When analyzing the experiences of single mothers, it is important to keep in mind that these characteristics are not causes but symptoms of a wider social issue (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:6). Many single mothers, especially low-income women, have been shown to see children as an opportunity to find unconditional love, escape negative home situations, and prove one’s worth and independence (Edin and Kefalas 2011:6). These women place child rearing before marriage, as they believe marriage to be a “luxury,” and child-rearing to be a “necessity” for attaining purpose and self-knowledge (Edin and Kefalas 2011:6). In this way, the role that marriage and child rearing plays in family structure takes on a different meaning, distinct from a normative, bourgeois perspective, but still valid and important in the communities that embody this new way of understanding family and motherhood. The lives of single mothers and their families are incredibly nuanced and cross-cutting, as single women raising children can be found in all communities, regardless of race, religion, class, etc, and as such, it is difficult to generalize the difficulties faced by these family structures without running the risk of stereotyping. In order to avoid this issue and provide an inclusive view of single motherhood, it is important to be aware of one’s own bias and experience with this topic, as well as to provide a wide range of sources and materials for understanding the case.

Synthesis

The theories of classical sociological founders are helpful for understanding the significant negative stigma that is attached to single motherhood. Primarily, by providing insight into the frameworks of society, sociology makes it possible to understand why single women raising children do not fit into these structures and are therefore stigmatized. The works of Friedrich Engels present one mode of examining family structure, and in analyzing his theories of inheritance, monogamy, and women’s subjugation, it becomes clear how single motherhood may suggest a threat to this order. Specifically, in Engels’ proposed system of monogamy for the preservation of paternal inheritance, it follows that a single woman raising children without a father poses a danger to this structure (Engels 2004:11). The children of single mothers historically represented an existence outside the realm of legal inheritance, and as such carried a stigma of illegitimacy which further removes single mothers and their offspring from normative social life. Although the threat of illegitimacy is less realistic in present-day, the stigma associated with it remains. Goffman’s concept of deviance is relevant here, as it explains why this type of divergence is perceived negatively by society: not only does a woman’s unmarried motherhood threaten the system of succession, it also disrespects its values, especially as many people perceive single mothers as the cause of their own challenges (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:10). Furthermore, an unmarried woman with children also implies a challenge to monogamy and the sequential order of marriage and childbearing as a strategy for preserving paternity. Single mothers resist the normative two-parent structure of patriarchal capitalism, and as such, resist traditional values and ideals.

While single motherhood may have been a legitimate danger to historical bourgeois family composition, Engels’ and Goffman’s theories do not explain why so many individuals in the United States, regardless of their class standing, continue to hold negative views of single mothers in a country which has nearly four times the rate (23% compared to 6.8%) of single-parent households of any other country in the world (Pew Research Center 2019). Gramsci’s concept of hegemony provides one possible explanation, as it explains why the values of the proletariat tend to align with those of the bourgeoisie, as the working class internalizes the values of a status quo passed down by the bourgeoisie through institutionalized societal and cultural structures (Gramsci 1992). Through government campaigns to promote marriage between parents and educational pushes to prevent teenage pregnancies, many key institutions clearly encode the message that single-parent households are undesirable in society (Edin and Kefalas 2011:4). However, single motherhood is a common reality for the poor and the working class, as nearly one-third of single mothers and their families live in poverty, and a much higher percentage qualify as low-income (Pew Research Center 2018). However, the negative opinion of single motherhood remains despite this common experience because of the hegemonic attitude of the bourgeoisie to view single mothers as a deviant threat to the order of their society, a value which has been passed down to the proletariat and become a widely-held belief.

While Engels’ and Gramsci’s theories provide insight into the threat single mothers pose to society’s structure and hegemonic values, the works of Perkins-Gilman are helpful in unpacking the specific difficulties present throughout the lived experience of single mothers. Specifically, Perkins-Gilman’s ideas, as well as, to a certain extent, those of de Beauvoir, elaborate on why single mothers occupy an inherently vulnerable position, putting them and their families at higher risk for poverty, abuse, and mental illness. One third of single-mother led families live in poverty, while single mothers simultaneously have twice the risk of depression and mental illness as other parent groups (Pew Research Center 2018, Brown and Moran 1997). The only factor linking these significant statistics is the nontraditional family structure of single mothers, thus demonstrating that it is motherhood itself which originates these challenges. Both theorists locate the ultimate origin of women’s oppression at the site of reproduction, similarly identifying motherhood as a role which consumes a woman’s individuality and causes her to lose autonomy. This might be a major reason why single mothers face such staggering mental health challenges, as their own selfhood is threatened by the results of their reproductive role, and jeopardized even further by the stress of poverty and financial burden.

Furthermore, Perkins-Gilman’s theory of economic dependence of women upon men provides strong reasoning for the financial challenges faced by single mothers, and a basis for the negative societal perception of such struggles. Namely, in a society in which single mothers are more likely to be in financial crisis than single fathers, it is clear that single mothers face a structure that favors men as breadwinners and poses challenges to women who must deviate from this norm (Lu et al. 2019). 63% of mothers who are breadwinners are single parents, so it is clear that the stigma and challenges around a single mother’s financial independence is not a result of actual lived experience (Wang, Parker, and Taylor 2013). Here, Gramsci’s theory of hegemony again offers one potential explanation, as the proletariat adoption of the bourgeois ideal of traditional gender roles could account for some of the financial discrimination women face as unmarried parents. Single mothers face a gap in the transition between mother and sole breadwinner, as many single women with children experience a vast educational disparity. As 50% of poor unmarried women gave birth to their first child before completing a high school degree, this disadvantage is doubly pronounced in already under-resourced groups (Edin and Kefalas 2011:2). While some single mothers may receive financial support from their families or their child’s father, this is not a universal experience and the ultimate responsibility for providing for their child’s survival falls, in the majority of cases, to the mother (Edin and Kefalas 2011). Therefore, not only do single mothers face the oppression of an already sexist, patriarchal system of earning and labor, they are also subjected to the stigma of a woman deviating from the hegemonic norm of the male as the main economic supporter and a woman’s role as domestic servant.

With these ideas in mind, Max Weber’s theory of social stratification becomes relevant for explaining the effects of the macrocosm of power on the lives of single mothers. Single women raising children have generally low economic power, as approximately one third of single-mother households live in poverty, therefore placing them in a low economic class. It is likely too that the two thirds of single mothers who do not live in poverty may be associated with this low economic status, as a result of the hegemonic negative perception of single motherhood (Lu et al. 2019). In general, women face pay inequality which becomes more pronounced with pregnancy and childbirth, a factor which increases the difficulties faced by single mothers who do not have other incomes to offset this struggle. This low economic rank predicts fewer life chances, and supports the idea that economic struggles are a large factor in the negative stigma of single mothers (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:10). Single mothers also struggle in the area of status, as their situation allows them little social honor. Goffman’s concept of deviance can be seen again here, as the perception of single mothers as rejecting society’s norms means that it is difficult for them to achieve social status within the same structure. Party is less relevant for this analysis, but perhaps aids in analyzing some sources of stigma applied to single mothers, as, for example, members of the conservative U.S. Republican party are some of the most likely people to have a negative perception of single mothers (Pew Research Center 2018). Overall, single mothers have the triple disadvantage of being low in class power and status group power, and generally being perceived negatively by certain parties in power.

Conclusion

In a country with the highest number of single-parent led families in the world, 66% of Americans still believe that single mothers have a negative impact on society, a tension which is deeply puzzling (Pew Research Center 2019, 2018). However, when analyzed through a classical sociological lens, it is possible to see that the reasons for this stigma are closely connected to the challenges faced by single mothers in society, leading to a troubling cycle of struggle and shame for female single parents. Taking the theories of Engels and Goffman, it is clear that in a patriarchal society in which the building of wealth was historically based on heterosexual monogamy, it follows that those who deviate from this norm are perceived negatively and experience difficulties as a result (2004, 1963). The value of heterosexual monogamy eventually became, according to the definition of Gramsci, hegemonic, perpetuated by the bourgeousie and upheld by the proletariat (1992). Single mothers do not fit into this ideal and therefore face both institutionalized challenges such as widespread poverty, mental illness, and abuse, as well as the stigma that is attached to deviation from social norms. On a micro level, the theories of Perkins-Gilman and de Beauvoir demonstrate that motherhood creates challenges for the personal development and growth of mothers themselves, an experience compounded by the challenge of solo parenting (1898, 2010). As such, single mothers struggle more than married mothers or men in areas such as educational attainment, earnings, and mental health (Caragata and Alcalde 2014:10). This analysis of single motherhood points to hegemonic standards for monogamy and the institutionalized difficulties for women as single earners as two top challenges that cause negative perceptions of single mothers. Overall, single mothers struggle in a system that was not designed to support them, and in many ways, seeks to deter them (Edin and Kefalas 2011:4). The overwhelming perception of these challenges will likely continue to be negative until the hegemonic ideal of a monogamous two-parent household shifts to include a more modern and inclusive value of diversity in family structure.

For single mothers and their children, the challenge of untangling perception from lived experience is deeply complicated, and requires much reflection. Social science and the sociological study of this phenomenon plays an important role in the push for self-knowledge, as it creates space in academia for the marginalized experience of single-mothers and their children. Through the academic pursuit of this topic, it becomes possible to change what is known about single motherhood, and in doing so, shift opinions with knowledge. Further directions for this topic would use the framework of this study to think more specifically about the intersections of other identities with single motherhood, such as religion, race, and sexual identity. Other future studies may focus more specifically on the individuals who hold negative perceptions of single mothers, and provide further analysis into the reasons behind their perceptions with a goal of creating specific strategies for improving the opinions of single mothers and their effects on society.

Overall, classical sociology adds nuance to the crucial concept that the struggles of single mothers and their families are symptomatic of wider social issues, not inherent characteristics of single mothers themselves. Sociological analysis allows for the separation of single motherhood from its perception in society, and with this new perspective, creates space for new ways of thinking about how these two factors both differ and intersect. In order to change the systems that produce hardship for single women and their children, it is essential to first identify clearly the wider institutional and societal causes of this phenomenon, and recognize their effects on both the individual and society. In this way, sociological analysis is an extremely relevant tool for explaining and affecting positive change on the issue of the stigma of single motherhood.

References

Beauvoir, Simone de. 2010. The Second Sex. 1st American ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Brown, George, and Patricia Moran. 1997. “Single Mothers, Poverty and Depression.” Psychological Medicine27(1):21–33. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004060.

Caragata, Lea, and Judit Alcalde. 2014. Not the Whole Story : Challenging the Single Mother Narrative. Waterloo, ON, CANADA: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Cherlin, Andrew J., Tera R. Hurt, Linda M. Burton, and Diane M. Purvin. 2004. “The Influence of Physical and Sexual Abuse on Marriage and Cohabitation.” American Sociological Review 69(6):768–89. doi: 10.1177/000312240406900602.

Edin, Kathryn, and Maria Kefalas. 2011. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood before Marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Engels, Friedrich. 2004. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Chippendale, N.S.W.: Resistance Books.

Engels, Friedrich, and Karl Marx. 2017. The Communist Manifesto. Minneapolis, UNITED STATES: Lerner Publishing Group.

Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma; Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1992. Prison Notebooks. edited by J. A. Buttigieg. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lu, Yuan-Chiao, Regine Walker, Patrick Richard, and Mustafa Younis. 2019. “Inequalities in Poverty and Income between Single Mothers and Fathers.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health17(1):135. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010135.

Perkins-Gilman, Charlotte. 1898. “Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Women and Economics.” in Women and Economics: A Study of the Relation between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution. Oregon State University.

Pew Research Center. 2018. The Changing Profile of Unmarried Parents.

Pew Research Center. 2019. Religion and Living Arrangements Around the World.

United States Census Bureau. 2016. The Majority of Children Live With Two Parents, Census Bureau Reports.

Wang, Wendy, Kim Parker, and Paul Taylor. 2013. Breadwinner Moms. Pew Research Center.

Weber, Max. 2009. “Class, Status, and Party.” Pp. 180–95 in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. London: Routledge.

Western, Bruce, Deirdre Bloome, and Christine Percheski. 2008. “Inequality among American Families with Children, 1975 to 2005.” American Sociological Review 73(6):903–20. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300602.