2 Chapter 2 Kelsey Braford

Image source: MicroStockHub/Getty Images Plus/Getty Images

The Stranger in Higher Education: Low-income Students Attending Wealthy Institutions

Kelsey Braford

Pomona College

December 8 2020

I. Introduction

As the national student loan debt continues to grow to insurmountable heights, it is a grim reminder that higher education is not affordable for many Americans. However, education remains an important aspect of social mobility, and the significant financial burden of education stands as nothing more than an attempt to gatekeep individuals from lower-incomes to gain access to the upper echelon of society. To understand how this functions from a sociological perspective, this paper will put Marx, Weber, and Simmel into conversation to draw several meaningful insights and conclusions from their work, and then apply these to the contemporary issue of inequality within higher education using Pomona College and the rest of the Claremont Colleges as a specific case study to examine this issue.

In his writings, Marx (1848) presents an economic understanding of society that centers around the functioning of capitalism as an economic system. He argues that economic disparities (and therefore social disparities) are intrinsically tied to capitalism. His ideas can be expanded upon to find that in the same manner that capitalism perpetuates wealth inequality, higher education perpetuates social inequality. Weber’s work (1922) can be seen as building off these ideas of class and inequality, as he makes assertions regarding what the sources of power are. He finds that status, class, and party are the three paramount pillars of power. These three factors, particularly status, are influenced strongly by educational attainment, and as such support the notion that higher education is an institution of inequality.

In the context of Pomona and the rest of the Claremont Colleges, historically wealthy institutions, we can apply Simmel’s concept of “the stranger” (1908) to understand how low-income students exist as a sort of “outsider” in this environment, filling the role of the stranger. Low-income students can be unfamiliar with the wealth they are surrounded by at prestigious institutions, and as such live and work in a society that might differ from what they have grown up in. This positionality allows them to have a unique perspective on the society of the Claremont Colleges to which they are unaccustomed, allowing them to also serve the function of the stranger to be a more objective viewer.

This paper will review the theoretical frameworks of Marx, Weber, and Simmel and then apply them to higher education to investigate the relationship between economic inequality, higher education, and power, and explore how low-income students can be thrust into the role of the stranger. The specific application of these ideas to the case study, Pomona College, will illustrate these concepts by presenting them in a literal context.

II. Review of Classical Sociological Theory

To begin, we will examine Marx and Engels’ work on economic inequality. Marx and Engels found that everything centered around the idea of class conflict, asserting that “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” (Marx and Engels 1848: 14). They felt that all of societies’ issues, including social inequality, ultimately stem from economic inequality. The bourgeoisie (the wealthy class) dominate the proletariat (the working class) through the structure of capitalism through which laborers are exploited. This exploitation is carried out through the model of capitalism in which the laborers are paid wages below the market price of their commodity, and capitalism is set up such that the proletariat work for wages (capital) rather than the actual product of their labor, and then they use that capital to perpetuate capitalism by purchasing goods produced by other, also exploited, laborers (Marx and Engels 1848).

Thus results social inequality. The bourgeoisie continues to profit off the labor of others while the proletariat remains captive to their own economic exploitation. The rich get richer while the poor get poorer. Higher education operates in a similar fashion; while with capitalism the wealthy hoard wealth (thus engendering both economic and social inequality), with higher education the educated hoard education. By maintaining a higher education system that better serves the most educated class, social and economic inequality are perpetuated because they prevent social mobility. Like how Marx says with regard to class, “private property is already done away with for nine-tenths of the population; its existence for the few is solely due to its non-existence in the hands of those nine-tenths” (Marx and Engels 1848: 23), so too is the distribution of education among different classes.

The way that education is gatekept to maintain this exclusivity is explained by David Brooks (2005) in an article for the New York Times. Brooks offered an explanation that also stands as a further analysis of how Marx’s views relate to higher education. Brooks argues that if Marx were alive today his manifesto would include higher education as yet another means of preserving class disparities. Brooks writes that “the educated class ostentatiously offers financial aid to poor students who attend [top] colleges and then rigs the admission criteria to ensure that only a small, co-optable portion of them can get in” (2005: 1). The high price tag of higher education serves as a strong boundary to prevent lower-income individuals from blurring the lines between the wealthy and the poor. Education remains a privilege enjoyed primarily by the wealthy because it maintains their monopoly on education and ensures “the continued dominance of [their] class” (Brooks 2005: 1).

This understanding is related to Bourdieu’s (1986) concept of cultural capital. Cultural capital, which is institutionalized in educational qualifications, is convertible to economic capital as it allows the individual to approach higher earning potentials. However, because it is accessible primarily to those who come from backgrounds of possessing economic capital, education “sanction[s] the hereditary transmission of cultural capital” (1986: 244). Furthermore, Bourdieu establishes a connection between social, economic, and cultural capital, arguing that they are interconnected and convertible to each other. Cultural capital can be transformed into economic and social capital, thus the hereditary nature of higher education makes it a channel to reinforce socioeconomic inequalities.

The works of Max Weber further support Marx’s assertions regarding inequality, but offer elaboration and contextualization, telling us why it is important. Weber found that there were three sources of power; status, class, and party (Weber 1922). Status can be understood as social prestige or honor (Weber 1922), which can be partially characterized by educational attainment. Class can be understood as wealth or economic positionality, as Weber asserted that class situation is ultimately market situation (1922). Party, a combination of class and status, can be understood as group affiliation or political influence, as parties characterize groups seeking power through organization (Weber 1922). Weber asserts that the degree to which these three aspects are possessed is determinate of one’s power in society. These ideas expand upon Marx’s rather simplistic representation of power and society as merely the competition between two distinct groups, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and presents additional factors that allow for a more nuanced take on power.

From this brief review of Marx and Weber’s works, we can conclude several things. Firstly, the structure of capitalism directly fosters economic inequality, and this engenders social inequality. Similarly, the structure of higher education amplifies economic inequality, further promoting social inequality. Secondly, Weber’s expansion upon Marx’s work offers a more complete picture of these social disparities as they relate to power, and they support the notion that class and social status (i.e. wealth and, to a certain extent, education) are determinate of one’s power. Finally, similar to how capitalism allows for the wealthy to retain wealth, the structure of higher education is set up to allow the educated (which is often synonymous with wealth and social status) to retain access to education, perpetuating educational disparities, and along with it wealth disparities.

Now that we have established the theoretical frameworks that contextualize the inequalities at play, we can transition to Simmel’s concept of the stranger and how it relates to this topic. Simmel argued that the stranger is an individual who is not a part of the society that they currently find themselves in. Distinct from the wanderer, the stranger is in the society but just not of it, essentially an outsider. A common example of an outsider is a migrant. While the stranger might not be able to fully integrate themselves into the society that they are entering, this is actually a strength. Since the stranger does not belong to the society, they are able to serve the function of being a more objective viewer;

Because he is not bound by roots to the particular constituents and partisan dispositions of the group, he confronts all of these with a distinctly “objective” attitude, an attitude that does not signify mere detachment and nonparticipation, but is a distinct structure composed of remoteness and nearness, in-difference and involvement. (Simmel 1908: 145)

According to Simmel, the stranger also has no power or status in the new society. This further lends to their ability to serve as objective, as they are able to view the group from a third party perspective because they are a degree removed from the society. This is nearly impossible for someone within the group to conjure.

As we will see in section IV, the works of these classical sociological founders remain relevant today and can be applied to modern examples to demonstrate their ideas in a familiar way. The example of how wealth interacts with higher education blends the work of these founders such that they complement each other and the interconnected application of them all best explains the sociological theory at play.

III. U.S. Higher Education and The Claremont Colleges

As put by Ronald Ferguson, Harvard’s director of The Achievement Gap Initiative, “educational inequality is, more than anything else, the fundamental root of broader inequality” (Education Gap 2016). Education is a key pillar of social mobility, yet ironically it is skewed to be significantly more available to those who rest near the top of the social ladder than those who stand to gain the most from access to education (social mobility wise).

In the United States it is abundantly evident that higher education is vastly more accessible to the wealthy. Individuals from poorer families are less likely to attend college (Pfeiffer 2018), less likely to complete their degree (Braga 2017), more likely to take out loans (Smith 2019), and less likely to get into top colleges (Whistle 2019). Reflecting similar trends in high-school graduation rates, over half of high-income children attend college, compared to 21% of low-income children (Fang 2018). Low-income students that do attend college do not get accepted to top colleges as often, either, as they are more likely to be accepted to community colleges or predatory for-profit institutions (Whistle 2019).

While the U.S. has made large strides to address educational equity among different racial, ethnic, and socio-economic groups over the past century, higher education is still gatekept by the excessive costs associated with it. Students from high-income families are over 1.5 times more likely to complete college than students from low-income families (Braga 2017). Furthermore, low-income students are more likely to have to take out loans to pay for education, another burden that does not exist for many high-income students (Smith 2019). The high cost of college ensures that minorities and low-income individuals will not be able to split from their marginalized position and break into the upper echelon of society. Brooks finds this phenomenon to parallel Marxist ideas, saying that “the information age elite [exercise] artful dominion of the means of production, the education system” (2005: 1).

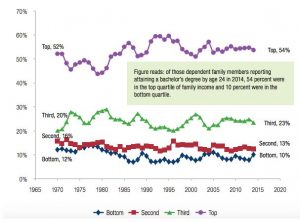

The wealth discrepancies among higher education students tell us that wealthier students have better chances of success in their educational endeavors than students from poorer backgrounds. The graph below depicts educational attainment as divided by four wealth quartiles. It shows that the top quartile of incomes accounts for over half of all bachelor’s degrees and reveals that the bottom two quartiles, or half of the population surveyed, account for a mere 23% of education. Alarmingly, these divisions among income quartiles have remained stagnant over decades. In fact, the bottom quartile’s share of Bachelor degrees has decreased slightly, while the top quartile’s share has increased. This data tells us that the current wealth gap in higher education is not a new trend, but a consistent pattern over time that, if anything, has only worsened.

Bachelor’s Degree Attainment by Family Income Quartile (1970-2015)

Source: Zinshteyn. “The Growing College Degree Wealth Gap.” The Atlantic, 2016.

The Claremont Colleges are very familiar with excessive tuition rates, with four out of five ranking in the top 30 most expensive colleges in the U.S. in 2020. According to CBS News, Harvey Mudd ranks third at $79,539 annually, Scripps ranks sixth at $77,588, Claremont Mckenna ranks twentieth at $76,475, Pitzer twenty-eighth at $75,850, and Pomona, while not making the list, comes in at $72,594 annually (CBS News, 2020). While Pomona is renowned for its generous financial aid, some of the other colleges, like Harvey Mudd and Pitzer, are notably not.

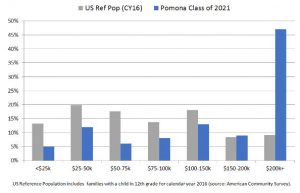

Pomona’s financial aid policy produces interesting outcomes. Pomona is committed to a very generous policy of meeting 100% of demonstrated financial need without loans. While this allows many students to attend who otherwise would not have been able to afford it, it also necessitates the high tuition rates for wealthier students and produces a situation in which there is little to no middle class at Pomona (as evidenced by institutional data, see the paragraph below). With a significant amount of the study body having family incomes that are characterized as low-income, and about half of students declining to apply for financial aid, Pomona has a very slim middle class. Approximately half of the student body comes from families with incomes over $200,000, while about 20% of students receive Federal Pell Grants (Pomona College Office of Institutional Research 2019). The chart below illustrates the dramatic gap between the financial backgrounds of students, showing that almost half of Pomona students are from very wealthy families, and demonstrating how Pomona’s economic demographics are very disproportional to those of the United States.

Pomona Family Incomes Compared to U.S. Reference Population

Source: Pomona College Office of Institutional Research, “‘Lighting the Path’ to Diversity,

Equity, and Inclusion at Pomona,” 2019.

This means that, for the most part, Pomona thrusts together the very wealthy with the very poor. The average financial aid award at Pomona is $52,748 (Pomona College Diversity Facts at a Glance). This means that students who receive aid tend to receive a lot. In contrast, half of students do not receive any aid (Pomona College Diversity Facts at a Glance). Since Pomona meets 100% of financial need, this means that those families can afford the $69,725 price tag (The Chronicle of Higher Education 2020). According to the New York Times, a new study has revealed that 52% of Pomona students come from families with incomes in the top 10% of the country (2017). Students from families with incomes over $110,000 paid 7.6 times more than students from families with incomes under $30,000 (The Chronicle of Higher Education 2020).

IV. Application of Sociological Theory to the Wealth Gap in Higher Education and Pomona College

Using Pomona College as a case study, one can clearly see the aforementioned theoretical frameworks applied. We will apply the ideas of all three sociological founders to this case, beginning with those of Marx and Engels.

In section II of this paper I asserted that higher education is one of the reproduction mechanisms of capitalism that perpetuates socioeconomic inequality. Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital (and how education is a major factor of it) is key to understanding how higher education affords some individuals greater access to economic (and social) capital in a hereditary manner, thus perpetuating inequality. Furthermore, with respect to Marx and Engels’ works, in the same sense that the wealthy hoard wealth, the educated hoard education and prevent widespread access to higher education by gatekeeping through excessive costs of attendance (see Brooks). Pomona actually stands in contrast to this, as their significant commitment to low-income students seeks to fight this phenomenon. By accepting a significant cohort of low-income students and making attendance affordable through generous financial aid, Pomona promotes social mobility and as an institution works against the social inequalities that are engendered by wealth and education gaps.

However, Pomona’s distinctly contrasting position presents other issues. As previously mentioned, their commitment to low-income students means that the student body is significantly made up of this demographic. In order to finance this policy, Pomona must also admit a significant number of students who are able to pay full tuition, leading to the situation we currently see at Pomona in which there is a very slim (and ever-dwindling) middle class. Interestingly, Pomona’s slim middle class seems to mirror Marx’s conceptualization of society as consisting of merely two groups; the haves and the have nots, or the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

Weber’s assertions on power expand upon Marx’s points and drive home the notion that status (which is partially comprised of educational attainment), class (wealth), and party (group influence) are significant determinants of one’s power. The status of an individual at Pomona might align with their socioeconomic status, but it also might align to their reputation, positive or negative, or their academic success/aptitude. A student’s class is obviously determined by their economic situation, however, in the microcosm of Pomona, it might be understood differently. For example, a student’s wealth is often not immediately apparent, and perceived class could be determined by indicators like their social circle, dorm room, or even meal plan. Lastly, at Pomona, the equivalent of political parties might look like the student government organization, the Associated Students of Pomona College, or another organization on campus that seeks (or maintains) some degree of power or influence.

To begin the application of Simmel’s notion of the stranger to this case, we will start by imagining a low-income student who attends Pomona. Picture this student as an individual who aligns more closely to their identity as low-income than any of their other intersectional identities. Imagine that this student hails from a poor family but, showing significant academic promise, was admitted to Pomona on a full scholarship.

Arriving on campus their first year, this student is somewhat of a stranger to the luxury and wealth of Pomona College. While a good portion of the student body identifies as low-income, that is not immediately apparent and the student does not immediately have access to these peers. Finding themselves to be in awe of the facilities, they are likely to feel a sense of imposter syndrome and stranger-ness as a low-income student attending a historically wealthy institution. While many students from wealthy backgrounds perceive the dorms and dining halls to be mediocre, a low-income individual might see the buffet-style meals and beautiful architecture as a sort of resort. This aligns strongly with the personal experiences of many students within the first-generation/low-income (FLI) association. These sentiments of imposter syndrome and feeling out of place in Pomona’s “resort”-like atmosphere are feelings that have been expressed by FLI students (often anonymously) through letter-writing campaigns, small mentorship groups, and other association events and programs, and they represent common experiences within this community.

Simmel also articulates that the stranger has no status or power when they enter the group. In the context of Pomona, the student has no status in the sense that they are not known to the student body – no one is aware of their socio-economic status and they have no reputation. Similarly, they also have no power according to Simmel. Weber’s definition of power supports this understanding, as he found power to be constituted by class, status, and party, and in the context of an incoming freshman they do not yet have a reputation or group affiliation. Without group belonging yet, or the establishment of status or class, the student is nearly indistinguishable from others.

While as time goes on the student will develop status and group and class affiliations, the low-income student remains an outsider. They remain in the society of Pomona College, but not of it in the sense that they are not from the same tier of society that Pomona and its student body (for the most part) aligns with. This outsiderness is both a vulnerability and a strength. While it makes them vulnerable to imposter syndrome and similar feelings of unworthiness, their positionality allows them to possess a “distinctly ‘objective’ attitude” (Simmel 1908: 145) with which they can use to make observations about the group that an insider could not.

There is more than one type of outsider at Pomona. Students of color, individuals with disabilities, LGBT students, and other marginalized groups are all “outsiders” to Pomona in both a historical sense and the sense that they are minorities in the current student body. Historically these groups have not been represented at Pomona, as the institution was founded only 25 years after the civil war, and has lived through decades of progression in American society. While today these groups are much more strongly welcomed through affinity groups, they remain minorities. However, these groups serve a key function for the institution as they can offer unique critical analyses due to their positionality. As evidenced by the 2019-2020 Campus Climate Survey, the college is purposefully listening to these voices more and more. They are dedicating bandwidth to addressing the issues that are important to their respective communities, while also using their feedback and experiences to inform the college’s improvements moving forward.

V. Conclusion

In summation, the classical sociological theories of the founders that we have examined in this class maintain their relevance. While developed in dramatically different eras, this essay demonstrates how their theoretical frameworks have endured the test of time, and can still be applicable to contemporary society.

Beginning with Marx and Engels, connections between capitalism and higher education were drawn that highlight not only how they parallel, but how they intersect. Higher education functions like capitalism in the sense that under capitalism the wealthy hoard wealth, and in higher education the educated (and therefore wealthy) hoard education (and therefore wealth). Capitalism prevents the poor from accumulating wealth, and higher education prevents less privileged individuals from obtaining education (and therefore power, according to Weber). Higher education is a mechanism of the reproduction of capitalism as it reinforces and amplifies existing inequalities.

Bourdieu’s work regarding cultural capital expands upon Marx and Engels and emphasizes the intersection of higher education and wealth. He explains that education is an aspect of cultural capital which can be converted to economic capital. Furthermore, the hereditary nature of higher education limits access to education for poorer and uneducated groups.

Weber’s understanding of power drives home why these ideas are important. Power comes from status, class, and party, and educational attainment is an important aspect of these factors (particularly status). For this reason, education can stand as an obstacle to power, gatekeeping the poor who cannot afford higher education from ever attaining substantial influence or power.

Finally, Simmel’s concept of “the stranger” can be applied to low-income students in higher education to both illuminate their experiences and highlight their positionality as a strength. The wealth gap in higher education fosters an environment in which the low-income student is positioned to be an outsider. The “stranger” who is in the group, but not of the group, experiences their surroundings with a perspective as they are slightly removed from the group. Since they are not entwined in the society, they are able to offer a more objective perspective than members of the society.

Pomona College served as an excellent case study for several reasons. It is an example that students are familiar with and as such they can more easily grasp the application of complicated concepts to the institution. In addition, the data necessary for this study was, while limited, readily available for affiliates of the college, whereas data from other universities would require requests for viewing and permissions for use. Standing in contrast to many other colleges, Pomona’s financial aid policy tries to bridge the gap for low-income students, making higher education affordable without crippling student loans and thus promoting social mobility. However, at the same time Pomona’s financial aid commitment can only be financed with a significant amount of students paying full tuition, and this balance between commitment to social mobility and financing it leads to a polarized spectrum of students’ economic situations With almost half the student body representing significant wealth, and the other half representing low-income to lower-middle-class incomes, Pomona has a thin middle class.

Using statistical data and other articles and sources to support the claims and assertions made in this paper, it is clear that Pomona, while an excellent example of an institution combatting financial obstacles to higher education, has created a microcosm in which the wealth gap in higher education is especially apparent. However, this situation is necessary to finance their assistance to needy students. The works of the founders of sociology can be applied to analyze the situation at Pomona, and understand the sociological implications of this. Further research in this topic area that could expand upon this analysis could be an investigation into the financial situations of all five of the Claremont Colleges, or other universities in America and abroad.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” Pp. 241-258 in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson. New York: Greenwood Press.

Braga, Breno, MckKernan, Signe-Mary, Ratcliffe, Caroline, Baum, Sandy. “Wealth Inequality Is a Barrier to Education and Social Mobility.” Urban Institute, 2017. www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/89976/wealth_and_education_4.pdf.

Brooks, David. “Karl’s New Manifesto.” New York Times, 29 May 2005.

“Colleges That Are the Most Generous to the Financially Neediest Students.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2020. www.chronicle.com/article/colleges-that-are-the-most-generous-to-the-financially-neediest-students/?bc_nonce=0g33ewbkveg5iujcew1lcl&cid=reg_wall_signup.

“Diversity Facts at a Glance.” Pomona College. www.pomona.edu/administration/diversity-pomona/facts-glance.

“Economic diversity and student outcomes at Pomona College.” The New York Times, 2017. www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/college-mobility/pomona-college.

Fang, Chichun. “Growing Wealth Gaps in Education.” Institute for Social Research Survey Research Center, University of Michigan, 20 June 2018. www.src.isr.umich.edu/blog/growing-wealth-gaps-in-education/.

Ferguson, Ronald. “Education Gap: The Root of Inequality.” Youtube, uploaded by Harvard University, 17 February 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lsDJnlJqoY.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. 1848. The Communist Manifesto.

Pomona College Office of Institutional Research. “‘Lighting the Path’ to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Pomona,” 2019. pomona.app.box.com/s/imjaq2p6rs2hi73tt5p7e6zofgv5xu7j

Simmel, George. 1971. On Individuality and Social Forms. London: The University of

Chicago Press.

Smith, Ashley A. “Study Finds More Low-Income Students Attending College.” Inside Higher Ed, 2019. www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/05/23/pew-study-finds-more-poor-students-attending-college.

“The 50 Most Expensive Colleges in America, Ranked.” CBS News, 2020. www.cbsnews.com/pictures/the-50-most-expensive-colleges-in-america/.

Weber, Max. 2009. “Class, Status, and Party” pp. 180-195 in From Max Weber: Essays in

Sociology. London: Routledge.

Whistle, Wesley. “Wealth Inequality And Higher Education: How Billionaires Could Make A Difference.” Forbes, 2019. www.forbes.com/sites/wesleywhistle/2020/12/31/wealth-inequality-and-higher-education-how-billionaires-could-make-a-difference/?sh=3237f5239db8

Zinshteyn, Mikhail. “The Growing College Degree Wealth Gap.” The Atlantic, 25 April 2016. www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/04/the-growing-wealth-gap-in-who-earns-college-degrees/479688/.