10 Workshop Six: Justice and Education in the Republic

DOWNLOAD WORKSHOP 6 HERE

Part I: General Instructions & Introductions (10 minutes)

For this workshop, you will be organized in a Zoom Breakout Room with a group of four to five students. If you have any questions or concerns, please send a message via Zoom asking for help. I’ll join you as soon as possible.

Please begin today by checking in with one another and looking over the workshop. This is a dense workshop that will demand your focused attention. Appoint a timekeeper and a scribe.

The workshop today includes a 10-minute break. We will take a second 10-minute break after reconvening to the main Zoom room. Please note the start time of your small-group work and the time when we will reconvene.

II. The Platonic Form (15 mins.)

- On a piece of paper, draw four different triangles, making them differ in both size and shape.

- Write down the definition of a triangle.

- Can you draw a picture which represents exactly what is represented in the definition of “triangle”? If so, draw it. If not, explain why it can’t be done.

- Let us call the four pictures you drew “images” of triangularity and the definition you wrote a representation of “true” triangularity. Is there such thing as the “true” triangle? Is it real? If so, where is the true triangle?

- Assume the “true” triangle is real. What might be the relationship that exists between it and your four images? What kind of correspondence exists between image and reality?

- Suppose you wanted to know the true triangle? What might you do to know it, or encounter it?

III. How to Perceive the Forms (or, Does Socrates have a Growth Mindset?) (20 min.)

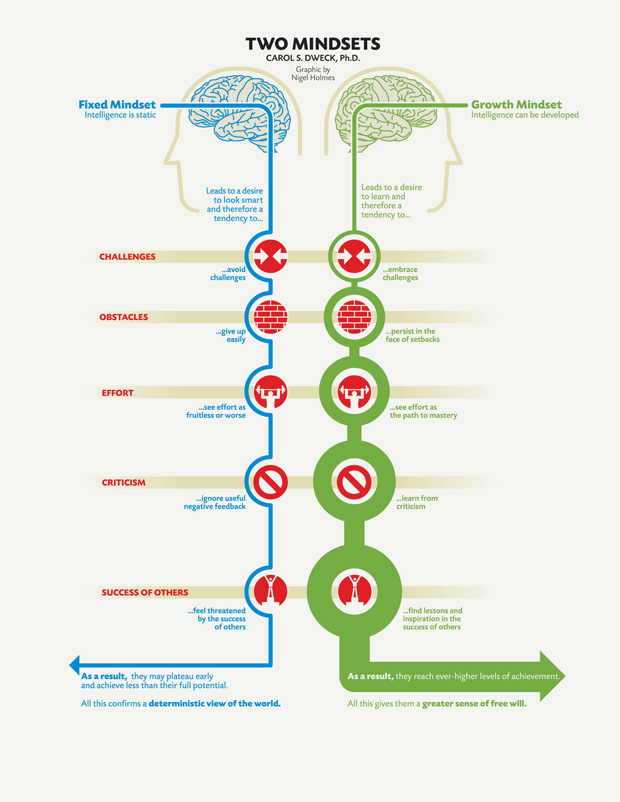

In her 2007 book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol Dweck introduced the model of Growth vs. Fixed mindsets. The two mindsets are illustrated by Dweck’s diagram, here. Please briefly discuss Dweck’s model and develop a working definition of “Growth Mindset” and “Fixed Mindset.”

Next, please discuss the following passages to determine whether you think Socrates supports a Growth or Fixed Mindset, or if you see a shift between the “Socratic” Socrates of the shorter dialogues and the “Platonic” Socrates of the Republic.

- “…one individual is by nature quite unlike another individual, that they differ in their natural aptitudes, and that different people are equipped to perform different tasks” (Republic Book II, 370b)

- “…they should assign each individual to the one task he is naturally fitted for…” (Republic Book IV, 423d).

- about the slave learning/”recollecting” geometry in Meno: “So he is now in a better position with regard to the matter he does not know? I agree with that too … Indeed, we have probably achieved something relevant to finding out how matters stand … Has he then benefitted from being numbed? I think so.” (Meno; 84b-c)

- “…we will be better men, braver and less idle, if we believe that one must search for the things one does not know…” (Meno; 86c).

Do you think Socrates promotes a growth mindset or not? Consider these follow-up questions:

- In Meno Socrates’ asserts that all people have all knowledge inside of them. How does this play a role in the idea of a growth mindset?

- How might Socrates’ promotion, or lack thereof, of the growth mindset affect the accessibility of Socratic dialogues. Would Socrates believe that everyone should be included in Socratic dialogues in the first place?

- In Book III, Socrates seems to equate an individual’s capacity to perform their occupation with their entire value and purpose. Discussing the type of doctor who would recommend to a carpenter that they cease their work in order to heal from an ailment, Socrates suggests that the carpenter would say “goodbye to this kind of physician,” because, Socrates affirms, “what profit in his life would there be if he were deprived of his occupation?”

- How does this statement shape your view of Socrates’ mindset? By today’s standards, to make productivity and value equivalent and definitive of an individual’s worth is problematic – as we can see in competitive environments, such as the Claremont Colleges. However, is it appropriate or useful to apply contemporary values to the Republic? On the other hand, is it possible not to?

IV. The Three Parts of the Soul (20 minutes)

- In an earlier, but still “Platonic,” dialogue, the Phaedo, Plato treats the soul as a homogeneous unity. He considers it immortal and to be that part of the person which “knows.” (In the Phaedo, as in the Republic, the objects of true knowledge are the Forms.) The discussion in that dialogue centers around the polarity of the soul vs. body. But in the Republic, he advances his analysis of the soul decisively, by arguing that the soul is made up of parts—three parts, to be exact—and that to understand souls one must understand the various possible relationships among the three parts. He thus establishes what may be called a systematic psychological theory.

The three parts of the soul are the rational part, the appetitive part, and the spirited part. The first two of these may be easy for us to understand. As Plato himself argues, we all sense and experience ourselves at times as split, with one part “desiring” something or other, and another part combating that desire, striving to prevent us from acting on the basis of that desire. With this part we seem to present rational arguments to ourselves in order to control and regulate desire. (“Doesn’t that which forbids in such cases come into play—if it comes into play at all—as a result of rational calculation…?” –439d)

But what of the third, less familiar part? At 439e, Plato asks, “Now is the spirited part by which we get angry a third part or is it of the same nature as either of the other two?” Review his argument (in the latter part of Book IV) in favor of the former alternative and see if you can make sense of it.

- What do you think of the hypothesis that the soul has separate parts? Evaluate this hypothesis by considering the alternative: that the soul is homogeneous and that when our soul acts, it acts as one undifferentiated entity (Plato’s view in the Phaedo). What are the advantages of Plato’s new “psychology” in the Republic?

- What do you think of the hypothesis that the soul has three parts (don’t worry for now about the nature of the three parts)? Evaluate this hypothesis by considering the two main alternatives: that the soul has two parts, and that the soul has more than three parts.

- Assume for the sake of the exercise that you have been informed by an omniscient being that the soul indeed does have three parts. Based on your own experience of life, how would you name or describe the three parts?

V. Please take a 10-minute Break.

VI. Justice in the Individual (20 minutes)

- It is easy to understand what Plato means by wisdom and courage, since each corresponds to the function and “virtue” of one specific part of the soul. But “moderation” and “justice” are more difficult, since they refer not to single parts of the soul, but to how the parts function together. First, read aloud and consider the following footnote from Grube’s original translation (adapted by Reeve in your edition) to 331c in which the translator explains that the word dikaiosune, translated as “justice,” actually has a much broader meaning than the English word. Unlike their usual equivalents “just” and “justice,” the adjective dikaios and the noun dikaiosune are often used in a wider sense, better captured by our words “right” or “correct.” This concept refers especially to good conduct in relation to others.” Always keep this note in mind during the ensuing discussions. (The Greek word for moderation is sophrosyne, often translated as “temperance,” and sometimes as “self-control.”) What does Plato mean by moderation and justice in the individual, and how are the two different from each other?

- Given your understanding of what Plato means by justice in the individual, why do you think this virtue seemed so important for Plato—so important that his dialogue on justice is ten times longer than his dialogues on the other virtues? What does justice do for the individual soul that none of the other virtues can do?

- One answer to question #2 is that justice is crucially important to the individual soul because it — and only it — is the means to achieving the unity of the non-homogeneous soul (a soul which is not by nature unified). Read aloud the crucial paragraph at 443d in which Plato summarizes the effects for the individual of having justice in his soul. Note the crucial sentence: “He binds together all of these, and from having been many things, he becomes entirely one, moderate and harmonious.” Grube’s original translation of the key clause here was: “He binds them all together, and himself from a plurality becomes a unity.”

Is it important for the individual’s soul or psyche to “become a unity”? What is life like, do you imagine, for those who remain a plurality?

- Consider the alternative argument. What argument could you make against unity and for plurality? Discuss briefly whether you think Plato is right or wrong on this question of unity.

VII. Justice in the City (30 minutes)

- What do justice and moderation mean when they are applied to the city—and how do they differ?

- Why is justice in the city so important to the city?

- When they finally discover what justice in the city means by seeing “what was left over,” they discover that it was the very first principle—the founding principle—of their city when they constructed it. The justification of this principle is given at 423d as follows: “each of the … citizens is to be directed to what he is naturally suited for, so that, doing the one work that is his own, he will become not many but one, and the whole city will itself by naturally one not many.” At 462b, Plato also puts the rhetorical question: “Is there any greater evil we can mention for a city than that which tears it apart and makes it many instead of one?” So Plato seems to value unity over plurality just as much for the city as for the individual. Why do you think Plato values unity so much for the city?

- In Book 3 of the Republic, Socrates advocates for a utopia in which they would “obliterate many obnoxious passages” from their religious mythology, specifically any tales of the gods being amoral. Would they be doing a disservice to the youth to shelter them from the ethically complicated stories which form the foundation of their belief system? For a utopia claiming to value truth above nearly all else, how is religious censorship justifiable? How is poetry a type of imitation which ought to be strictly forbidden, yet painting the gods as paragons of virtue is acceptable? How do these recommendations fit in with the larger aims of unity in the Republic? Is polytheism inherently at odds with the aim of unity?

- Why do you think Plato wants to organize the guardians on the model of the family, that is, to have them hold their wives and children in common, so that all of the guardians treat each other as brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers, sons and daughters?

- Plato seems to want to extend this model of the family to the Greeks as a whole! He calls the Greeks “its own and akin” and says that when Greeks fight Greeks (as opposed to barbarians), “Greece is sick and divided into factions.” (470c) Plato seems to take models of “organic unity” from the examples the healthy body and the natural family and to establish them as ideals for the individual soul, the well-governed city, and even Greece as a whole. What is it about unity that makes it seem so desirable at all these levels?

- Throughout the Republic, there exist some glaring contradictions, especially concerning the roles of women in Socrates’ ideal State. For example, he says in Book IV that women (and children and servants) will never be virtuous by themselves, that they will always be held down by “the wisdom of the few.” However, after this, he says that a select few women would be able to attain the same virtuous status as men through education. This is just one example of a contradiction in the text. What does the existence of these contradictions mean for Socrates’ overall argument and his own credibility?

- If you did not bring up the issue of stability in your response to question 6, then consider it now. What is the natural relationship between unity and stability? How does harmony fit into this constellation? What about beauty? And finally, how are peace and friendship connected to the complex unity/stability/harmony?

VIII. Conclusion (15 minutes)

To tie together the various parts of this workshop, we have to recognize that the complex “unity/stability/harmony” applies not only to the soul and the state, but also to objects of knowledge—The Forms. We can now recognize that, for Plato, there are parallels not only between the internal ordering of the soul and the external ordering of the city, but also between the ordering of the soul and the truth. The soul must be in the very same well-ordered condition to rule a city as to apprehend the truth.

Can you now explain why the rulers must be lovers of wisdom (literally, “philosophers”) and why details of education take up so much of the text of the Republic? Try to. (10 minutes)

Once you have developed your answers to the above questions, please revisit the Allegory of the Cave. Review the passage at 520b-e. Reflect individually for the final 5 minutes of this workshop on these questions, with the intention of reporting out to the reconvened seminar.

- What do you make of the experience of going back into the cave?

- Have you had an experience of “returning to the cave” similar to what Socrates describes?

- Do you believe in forcing people to return to the cave to make the whole society better?

- What does this analogy have to do with the experience of teaching?