1 The Effect of COVID-19 on The Toll of Women and The Subsequent Care Policies Implemented by The Latin American Governments – Mayra Coruh

M. Coruh

How did the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbate the toll care work creates for women and what are the subsequent care policies that the Latin American governments implemented in response?

Introduction: Care Work, The Pandemic, and The Situation in Latin America

Mainstream feminism associates women’s liberation with work outside the home by glorifying women who have successful careers. Such admiration neglects the inevitability of women’s boundness to housework. Even though most women who are mothers face a motherhood penalty, rich women can afford caretakers or domestic workers, while poor women have no chance but to comply with low wages since they often have disadvantaged social backgrounds. Even if women have a career outside of their homes, they are obligated to engage in care work due to traditional gender roles that are imposed on women (European Institute for Gender Equality). So, they need outside financial support to mitigate the time spent doing unpaid labor (Jain 2022). The work they do in the home should be acknowledged. This leads to the concepts of paid and unpaid care work. In general terms, care work can be defined as “[a]ny labor involving looking after the physical, psychological, emotional and developmental needs of people. While some care work falls under the formal labor market, a majority of care work is unpaid” (Kaplan 2021).

Societies rely on care work, which is essential to the economy. However, women and girls perform more than three-quarters of the total amount of unpaid care work and two-thirds of care workers are women (International Labour Organization 2022). Additionally, the demand for care workers is increasing due to demographic, socio-economic, and environmental changes. However, care workers are often under-compensated or not compensated, leaving few people willing to work these jobs. This can lead to a severe and unsustainable global care crisis. If left unaddressed, the existing deficits in care work and its quality can further deepen gender inequality in the workforce (International Labour Organization 2022).

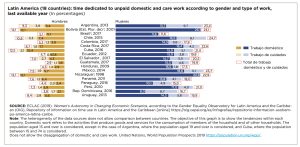

In Latin America, as in most areas of the world, care work is disproportionately distributed since the responsibilities of care work are carried out mainly by women who are unwaged, with women performing 76% of total hours of unpaid care work prior to lockdown (Hasselaar and Jimenez 2020). The significance of their work is often unrecognized and undervalued in economic and social policies in Latin America. On the other hand, paid care work typically provides low wages and precarious working conditions coupled with 93% of paid domestic workers being women in Latin America, reinforcing the stereotype of feminized care work that is undervalued (Loza 2023:187). With the COVID-19 pandemic, care work became a central issue since a global crisis in the health sector brought with it the need for receiving and providing care. Accordingly, in this paper, I will explore how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the toll that care work created for women and the subsequent care policies that the Latin American governments implemented. I will do so by examining these events and policies using the frameworks of Social Reproductive Theory, Marxist feminism, Intersectionality, Pandemic Mothering, and care policies and presenting information on social movements during the pandemic that relates to my argument.

-

Theoretical Frameworks That Relate To Care Work

1.1. Social Movements In The Pandemic

To examine how recognition of care work performed by women in Latin America was developed during the pandemic, it is necessary to take a general approach and talk about how social movements were impacted during this global crisis. In my analysis, I will show how this phenomenon helps answer the question of how Latin American governments noticed the importance of care work and took action to help people engaged in it. “The pandemic and lockdown occurred in a specific historical context that deeply affected social movements” (Pleyers 2020:2). However, although social movements faced many challenges in this period, they played some crucial roles that can theoretically and epistemologically be analyzed through three sets of arguments (Pleyers 2020).

First, there was a shift of focus from protests to less visible aspects of social movements. To elaborate, unlike popular opinion, which would consider the lockdown period as one of latency since there was a lack of demonstrations, social movements were active during the pandemic in unconventional ways. It can be said that a new approach to social movements was presented, which is embedding activism into daily life by building solidarity within communities beyond activist circles (Pleyers 2020). In my analysis, I outline how this new approach to social movements during the lockdown were impactful in stimulating the Latin American governments to take action in policymaking even though this happened in traditionally less visible ways.

Second, the majority of research on mobilizations concentrates on a national level. However, the roles and challenges of social justice movements across different continents are also important. The viewpoint presented supports a global perspective on civil society that challenges methodological nationalism and instead utilizes transnational analytical categories. It is important to note that recognizing the global aspects of a movement does not imply that the actors and contexts involved are all the same, nor does it involve ignoring local and national dynamics. This perspective supplements earlier research on movements and civil society that concentrated on local or national actions, particularly during the period of lockdown (Pleyers 2020). I refer to this argument in my analysis to show how social movements were effective in the creation of policies post-pandemic due to their work in the transnational sphere.

Lastly, the agency of movements in times of crisis as well as the pandemic opening opportunities for the construction of a fairer world must be taken into account. Social issues that were being tackled solely by popular movements were worsened in the pandemic, yet solidarity between popular movements, citizens, and grassroots organizations was created. Because there were activists and intellectuals advocating for increased public interest, people were more interested in how the government was dealing with the global crisis. This public interest led to monitoring public policies, governments, and policymakers (Pleyers 2020). In my analysis, I show how increased public interest in care work incited change in policy and government actions.

Their analysis reveals that the ways in which the virus spreads are profoundly intertwined with social inequalities. Such outcomes are necessary for monitoring lobbies and influencing policymakers for positive social change to take place. Accordingly, the fact that social movements in the pandemic were active in different ways when compared to the past and that social movements and policies are interrelated provides an important theoretical framework that might suggest how social movements can facilitate policies. It is also worth mentioning the approach taken by international organizations in addressing social issues that establish a contradiction with that taken by social movements. International organizations tend to adhere to a globalist mindset that supports the development industry which leads them to come up with one-sided solutions, resulting in blind spots that prevent the tackling of global issues like care work (Rodrick 2017) (Easterly 2001).

1.2. The Toll of Care Work For Women In The Pandemic

Social Reproductive Theory (SRT) and Marxist feminism are theoretical frameworks that are relevant to explain the burden of care work performed by women. SRT revolves around the production and reproduction of labor power under capitalism (Jaffe 2020:1). It offers a general framework to comprehend how social relations shape labor powers and their potential for production and reproduction (Jaffe 2020:1). SRT values diverse labor powers and argues for conditions that allow for the realization of these powers beyond exploitative social dynamics (Jaffe 2020:1). In the context of SRT, Marxist theory has relevance. The fact that SRT points to the totality of social relations that are produced and reproduced within capitalism makes a reference to Marxism with an implication that labor is central to the creation and reproduction of society (Jaffe 2020:2). To be more precise, Marxist feminism is “an emancipatory, critical framework that aims at understanding and explaining gender oppression in a systematic way” (Sheivari 1970:1142). It can be asserted that a Marxist account of labor does not recognize care work, which makes it vulnerable to exploitation because it takes place in the domestic sphere outside the market economy. Hence, Marxist feminists extend Marxist theory for it to encompass the concept of unpaid domestic labor. They argue that despite the marginalization of domestic work, it is still a form of work that deserves recognition. Unlike the Marxist view of exploitation, which focuses on exchange value and wages, domestic care work is not considered a market commodity and is not associated with a wage (Tahmaseb 2021:2). I reemphasize Marxist feminism in analyzing the significance of the care policies in tackling the care crisis in Latin America by going beyond pre-existing societal boundaries.

The theory of intersectionality establishes a nuance in the context of Marxist feminism and STR. People with multiple intersecting marginalized identities can face even further inequalities. This is because inequality deepens when marginalized identities are layered upon each other – when a person has more layers of marginalized identities, they’re more affected by social inequities, especially regarding care. This is essentially because unequal distributions of care labor become more complex and therefore damaging when layers such as gender, race, ethnicity, class, and nation are involved in addition to the already existing sexual divisions since such markers of identity are effective in determining the people who will take on a greater or lesser amount of the work (Weeks 2011) (Orozco 2009). Associated with this is the time used between men and women in care work. Aguirre and Ferrari argue that to better understand the differences faced by different population groups in terms of care work and accommodate their varying needs, methodologies that merge the qualitative (e.g. interviews) and the quantitative (e.g. time-use surveys) are important (Aguirre and Ferrari 2013).

Some analysts claim that on a global level, gender analysis reveals the growing commodification of care work which interacts with migration patterns through the feminization of international migration mostly from lower-income countries. In other words, the circulation of female workers in the global care chains must be analyzed from the lens of intersectionality: “a gender perspective that observes the geopolitics of migration and its materiality in each household” (Loza 2023:189). Furthermore, the relationship between immigration and paid care work relates to social reproductive theory. Paid and unpaid care work are both crucial for the social reproduction of societies and tackling crises concerning reproduction such as low fertility rates and shortages of caring labor, threatening the reproduction of the labor force needed for the economy, and families not being able to afford paid care, interfering with their decision to have children (Beneria, Deere, Carmen, and Naila 2013). Considering such cases, immigrant labor can be presented as a way of dealing with the shortage of care labor. However, such a care chain grounded in migration comes with obstacles since women who migrate to engage in paid care work are solely able to fulfill unpaid care responsibilities to their families by leaving them behind and taking on paid care work opportunities for others elsewhere. The situation shows that even established care chains have deficits, resulting in a vicious cycle of a constant demand for care work which does not allow all caretakers to receive wages, thereby reinforcing the problem and burden of unwaged care work on women (Beneria, Deere, Carmen, and Naila 2013).

Narrowing the discussion down to the toll of care work for women in the pandemic, the theoretical concept of “pandemic mothering” suggests that “mothering is gendered and the labor and responsibility of caring for children and other family members are mostly taken on by women and mothers” (Green, Joy, and O’Reilly 2021:929). This situation was heightened during the pandemic since there was a “lack of acknowledgment and support for them and their motherwork that was so essential during this time” (Green, Joy, and O’Reilly 2021:929). “Pandemic mothering” is part of the “fourth shift” of domestic labor, and refers to the additional unpaid work that falls on women, as well as the tensions between paid and unpaid labor (Green, Joy, and O’Reilly 2021). Mothers in the paid workforce were especially negatively impacted by the increased burden of caregiving responsibilities due to the disproportionate distribution of unpaid work at home. While women working in the health care sector experienced extreme working conditions, such as long working hours, they also faced the challenge of the duplication of labor since women working in the health system were still responsible to care for people in their households (Loza 2023:191). According to a Canadian study, men spent an average of 33 hours per week on caregiving prior to the pandemic and 46 hours during the pandemic as opposed to women who spent an average of 68 hours before and 95 hours after (Green, Joy, and O’Reilly 2021:933). Such an excessive workload surrounding care exacerbated the “third shift” of emotional and intellectual labor associated with motherhood, underscoring the toll in terms of the arduous nature of the care work women inevitably carried during the pandemic (Green, Joy, and O’Reilly 2021:933). I use the concept of “Pandemic mothering” in the analysis of the subsequent care policies implemented by Latin American governments since the measures taken addressed the “fourth shift” and “third shift” COVID-19 created for women.

1.3. Care Policies

Care policies, which will later be mentioned in the context of those implemented in Latin America, is a concept that is central to the discussion on the care crisis. Within social and public care policies, it is important to talk about the role that multilateral organizations and agencies play in their creation and application. Support by powerholders to the care domain through policymaking is a necessary element for social change. However, policies addressing the care crises are either nonexistent or inadequate which interferes with the incentive of improving the status of care work (Orozco 2009). In the third section, I analyze how care policies were brought into being in Latin America with the help of activities in the political sphere.

-

The Case: Exacerbation of The Toll of Care Work Created For Women In The Pandemic and Subsequent Care Policies in Latin America

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latin America, a region known for having inadequate and unstable social systems for providing care, made the reality faced by women involved in paid and unpaid care work visible through the acknowledgment that their work is integral to the sustenance of economies and societies. Women in Latin America did three times the number of hours of unpaid work than men before COVID-19. Lockdowns and curfews in the pandemic significantly increased care work performed by women in the household due to the rising demand for care and reduced supply and services. The exacerbation of the toll of care work created for women in the pandemic acted as a stimulus for some Latin American governments to understand the importance of these duties and their reliance on unfair gender-based division. This recognition motivated them to redevelop their care systems. Hence, Latin American governments took action to promote a shared responsibility for caregiving among genders, States, families, and the market. This happened for the purpose of building more social, economic, and gender-just social systems while also maintaining an equitable distribution of care work between men and women and between the State and societal sectors. The policies they presented include services for those in need of care, parental leave for caregivers, and financial support for care services.

The Santiago Commitment was adopted in 2020 to reduce the damaging impact of economic crises on women’s lives including their care work (UN Women 2020). It is worth noting that this commitment remained merely as an attempt to better women’s lives in the context of care work since Latin American governments did very little in response to it. However, with the global health crisis making the inequities in caregiving even more apparent, significant developments in terms of the recognition, distribution, and reduction of care work were seen in some Latin American countries post-pandemic through measures adopted in the region regarding care in response to COVID-19. The measures can be evaluated under the following different categories: “Licenses and Permits,” “Services,” “Cash Transfers For Care Work,” “Campaigns To Promote Co-Responsibility,” “Support for People With Disabilities,” Exceptions To Restrictions on Movement,” and “Rights of Paid Domestic and Care Workers” (UN Women 2020:21). For instance, in Ecuador, The National Council for Gender Equality put forth an information campaign concerning the co-responsible nature of care. The campaign stressed the burden of unpaid care work on women in the context of health emergencies and the necessity to promote co-responsibility in caregiving during the pandemic (UN Women 2020:21). In Cuba, the family member who is in the workforce but is also in charge of caregiving was to receive a wage guarantee of 100% of the basic salary in the first month and 60% until their work was unsuspended (UN Women 2020:21). In Argentina, an “Emergence Family Income” was established for unemployed people, informal workers, and workers employed in private homes (UN Women 2020:21). A campaign under the hashtag “Quarantine With Rights” was launched to promote the equitable distribution of household chores (UN Women 2020:22). In Uruguay, the reinforcement of transfer programs such as the Uruguay social card and allowances for dependent children were set in order to support women’s economic livelihoods (UN Women 2020:21). These measures adopted in response to the pandemic demonstrate that various Latin American governments became aware of the exacerbation of the toll care work created for women during the pandemic.

-

The Analysis of Care Work In Latin America Through Literature About Feminist Theories of Labor

The transformation of social movements especially in terms of the focus on less visible aspects of the movement during the pandemic explains how Latin American governments took notice of the exacerbation of the toll that care work created for women and took action to tackle the severity of the care crisis with the emergence of the pandemic. More precisely, the new pandemic-induced approach to social movement guides the exploration of the factors that stimulated the governments to implement care policies to lessen the toll care work created for women since the care crisis was an already existing phenomenon that was not given much attention.

The care crisis had a significant impact on media coverage, transnational networks, and social organizations. The unions and organizations that gather domestic workers in Latin America allowed for the maintenance of an ideological convergence and facilitated cooperation during the lockdown period. The exacerbation of the effects of care work on women with the global health crisis led to community care actions and the prevailing of pre-existing solidarity networks (Loza 2023). This indicates that social movements and political mobilizations surrounding the care crisis in Latin America engaged with supporting women in alternative ways, “[o]pening new possibilities in terms of regional and international cooperation and coordination for women’s movements” (Loza 2023:182). Building solidarity between communities in unconventional ways aligns with Pleyers’s first argument of how, with the emergence of the pandemic, there were less physical aspects of social movements. This also fits with Pleyers’s third argument that touches upon the effectiveness of public interest since public interest gathered via building connections were integral in stimulating policymakers. The experience of the regional coalition of paid domestic workers: Confederación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Trabajadores Hogar (CONLACTRAHO) is vital to consider in its efforts on a “[r]egional scale of using a political strategy of pressure towards governments that should adopt specific measures to improve women’s lives” (Loza 2023:192). In this way, while these movements were important on a national scale, the fact that the tackling of the care crisis post-pandemic branched out to be on a transnational scale supports Pleyers’s second argument of how there was a tendency for a global perspective on social issues to be embraced.

CONLACTRAHO showed support by disseminating information about paid domestic workers in the region to raise consciousness in society, collaborating with other organizations to achieve policy influence, giving recommendations for policy intervention, and expanding the recognition of labor rights for women through national governments of the region and intergovernmental organizations (Loza 2023:190). CONLACTRAHO’s efforts in the care crisis demonstrate Pleyers’s first argument of embedding activism into daily life in seemingly less visible but powerful ways. The transnational aspect of tackling the care crisis is evident in the outreach campaigns based on updated information on the conditions of women workers in the region during COVID-19 by CARES, a US-based organization that supports CONLCACTRAHO, portraying Pleyers’s second point of how there was a shift from a national to a transnational approach to social movements with the onset of the pandemic (Loza 2023:190).

Furthermore, the ILO, UNDP, and ECLAC are intergovernmental organizations that advocate for regularization in national contexts to enhance working conditions and boost the strength of domestic workers’ unions. To ensure a diverse and intersectional approach toward government strategies, coordinated action between various organizations at national, regional, and international levels remains the primary approach. This approach involves engaging women’s organizations, feminist organizations, migrant organizations, grassroots communities, as well as indigenous and Afro-descent groups in developing strategies for impact, tying into Pleyers’s third argument of how although social issues that were merely dealt with popular movements lost effectiveness, solidarity movements between popular movements, citizens, and grassroots organizations were influential.

The role of social movements on the care crisis in Latin America during the pandemic shows that social movements were still active, but engaged with social issues in less apparent ways like protests or demonstrations, which is put forth through Pleyers’s first argument. Instead, social movements took an approach that valued transnationality through media coverage and outreach activities that created a significant amount of impact for the vocalization and the exacerbation of the toll care work created for women during COVID-19 which was integral in the issue to be recognized by Latin American governments for the implementation of policies. This connects to Pleyers’s second argument of how the stimulation of public interest is influential in alarming the government to take action through taking measures. Additionally, as mentioned by Pleyers’s third argument of how solidarity and public interest facilitates the implementation of policies, the role of social movements was strengthened through the solidarity between popular movements, citizens, and grassroots organizations and the public interest that led to the stimulation of governments for care policies. Ultimately, it can be said that the patterns, which are also outlined by Pleyers, of social movements during the pandemic in Latin America have generated positive political outcomes in the making of policies to support women care workers during the pandemic.

Latin American feminist economists have been saying for a long time that there are certain challenges to implementing the care agenda in Latin America, such as establishing short-term public policies surrounding care that are not supported by laws and reforms, not taking into account the feminist perspective in approaching care measures, not considering gender co-responsibility in caregiving, and the minimal or non-existent recognition of public policies by different political bodies. These challenges might prevent the implemented care measures to play an effective role in Latin American women who are in the care industry. Feminist economists claim that care policies should be established as long-term public policies supported by laws and reforms that ensure their funding from government administrations. Policymakers should be looking through a feminist lens to avoid the reinforcement of gender roles and sexual division of labor through policies. For instance, providing care benefits exclusively to women, such as extended maternity leave without offering similar benefits to fathers, increases women’s caregiving responsibilities. Furthermore, campaigns and cultural transformation strategies in education are vital in raising awareness of gender co-responsibility in caregiving. Finally, public policies are more effective when they are also acknowledged by distinct governmental structures and social actors hence such actors should be active in the making of care policies (Villegas Pla 2022).

Many of these considerations are present in the measures taken by the Latin American governments with the emergence of the global health crisis. For example, policymakers have shown that they look through a feminist lens by launching campaigns to promote the equitable distribution of household chores (refer pg.10). Additionally, the fact that the framework of care policies (refer to pg. 8, “1.3. Care Policies”) suggest that public policies become more effective when multinational and transnational organizations and agencies and social actors participate in their creation and application of them can be applied to the presented case since in Latin America the measures taken by the governments were influenced by the cooperation of international organizations such as the ILO and ECLAC as well as the regional efforts by social actors such as the CONLACTRAHO. These illustrate that although challenges to care policies exist, Latin American governments are working towards taking them into account. However, this does not mean that they are considering overcoming these challenges which is an indicator of the success of social change that is being cultivated in shifting the dynamics of the care crisis in Latin America.

The measures taken by the Latin American governments such as those of Argentina, Uruguay, Ecuador, and Cuba (refer to pg. 10) in the context of the care crisis that was heightened due to COVID-19 address the “fourth shift” of labor that entails the additional labor women are responsible for inside the house and the “third shift” of labor that entails the emotional and intellectual labor women take on. All the policies that were implemented by these governments are targeted toward women who had to take on an additional shift of taking care of the household more than they ever had to, which inevitably created an emotional and intellectual burden on them. The measure of the family member who is the caregiver in the house and is in the workforce receiving a wage guarantee in Cuba is a direct example of how the care policies implemented due to the global health crisis are meant to lessen the physical and mental toll excessive care work created on Latin American women.

The transnational and regional efforts by social actors and intergovernmental organizations and the subsequent measures taken by various Latin American governments establish an opposition to the Marxist view of labor which does not recognize care work and hence does not associate it with a wage. The creation of policies, however, echoes Marxist feminism which encompasses unpaid domestic work and advocates that it is a form of work that deserves recognition. This way, it goes beyond the existing societal and economic structures rooted in Marxist ideals that are ignorant to the pandemic-induced aggravation of the toll that care work has on Latin American women. Alternatively, the Social Reproductive Theory’s argument for conditions that allow for the realization of powers beyond exploitative social dynamics is important to bring into the analysis. This is essentially because the efforts by social actors in policymaking and the consequential policies demonstrate that Latin American governments have realized and acted upon exploitative social dynamics of unequal distribution of care work among genders and the lack of or insufficient wages for care work. The shift in social relations this brings in turn shapes labor powers and their reproduction and production patterns in a way that is more inclusive and just.

Conclusion

In this paper, I explain how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the toll that care work created for women and the subsequent care policies that the Latin American governments implemented. I put forth that Latin American women were emotionally and physically impacted by the additional care work they had to undertake within their own households during the pandemic. This was recognized by certain Latin American countries such as Uruguay, Argentina, Cuba, and Ecuador and policies were implemented to preserve women’s rights in terms of the burden care work put on women. I analyzed this situation through the frameworks of the change in social movements during the pandemic, the Social Reproductive Theory, Marxist feminism, and Pandemic Mothering to further understand how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the toll care work created for women and the subsequent care measures that the Latin American governments adopted.

Although there has been progress in terms of organizing paid domestic workers at a transnational level and incorporating domestic work into the gender agendas of regional organizations, there is still a significant discrepancy between current legislation and the reality experienced by women who work as domestic workers. Despite these efforts, the situation remains quite dire for many women employed in this sector. Through policies and measures, some Latin American governments have implemented assistance programs to address immediate needs, but these programs do not sufficiently tackle the underlying structural inequalities. It is worth noting that Latin America has the highest number of countries that have ratified Convention 189, which pertains to domestic workers’ rights. However, progress has still been sluggish, with only Argentina and Uruguay making tangible strides in creating legislation that aims to formalize paid domestic work. This is significant because a large portion (around 80%) of the domestic work sector in Latin America remains in the informal economy (Loza 2023:190).

Accordingly, future follow-up research could evaluate the extent to which the measures taken and the policies implemented by Latin American governments to tackle the care crisis that heightened with the pandemic have actually created a difference in the lives of women struggling with the toll of care work. Although such political adjustments do need time to effectively impact the targeted population, it is important to be aware of whether the outcomes meet the goals in order for sustainable social change to be created in the context of making life better for Latin American women who are emotionally and physically affected by care work they have to perform especially with the onset of COVID-19.

References

Aguirre, Rosarrio and Ferrari, Fernanda.“Surveys on time use and unpaid work in Latin America and the Caribbean”. United Nations, ECLAC, 2013.

Belén Villegas Plá. Gender | Society, and Name. “Care Policies in a Post Covid-19 Scenario in Latin America: LSE Latin America and the Caribbean.” LSE Latin America and Caribbean blog, 2022.

Beneria, Lourdes, Diana Deere, Carmen, and Kabeer, Naila.“GENDER AND INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION: GLOBALIZATION, DEVELOPMENT, AND GOVERNANCE”. Feminist Economics, 2012.

UN Women. “Care In Latin America and The Caribbean During The Covid-19 – Towards Comprehending Systems To Strengthen Response And Recovery”. ECLAC, 2020.

“Care Work.” European Institute for Gender Equality. https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/terms/1059

Aaron Jaffe. “Social Reproduction Theory and the Form of Labor Power,” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, Purdue University, 2020.

Easterly, William. “Elusive Quest for Growth Conclusion: The View From Lahore,” MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2001.

Elselot Hasselaar and Andrea Saldarriaga Jiménez. “The COVID-19 crisis disproportionately affects women – here’s how Latin America is addressing it.” World Economic Forum, 2020.

Green, Fiona, Joy, and Andrea O’Reilly. “Pandemic Mothering.” Maternal Theory: Essential Readings, The 2nd Edition. Demeter Press, 2021.

International Labour Organization. “World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2022.” Geneva, 2022.

Jorgelina Loza. “Social Movements, Care Crisis, and New Opportunities for Regional Cooperation: The Regional Integration of Female Domestic Paid Workers in Latin America.” International Relations Department, FLACSO/CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023.

Kaplan, Sarah. “Care Work.” Gender and the Economy, 2021.

Orozco, Amalia. “Global perspectives on the social organization of care in times of crisis:

Assessing the situation,” 2009.

Pleyers, Geoffrey. Journal of Civil Society, 2020

Rodrick, Dani. “Why Nation States Are Good.” Harvard University, 2017

Shraddha, Jain, “Book Review: Selma James, Margaret Prescod, Nina Lopez, Our Time Is Now …” Indian Journal of Human Development, 2022

Sheivari, Raha. “Marxist Feminism.” SpringerLink. Springer New York, 1970.

Tahmaseb, Alicia. “Rerum Causae.” Rerum Causae: Student Journal of Philosophy. Houghton St Press, 2021.

Vereinte Nationen Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. “The Covid-19 Pandemic Is Exacerbating the Care Crisis in Latin America and the Caribbean.” United Nations, 2020.

Weeks, Kathi. “The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries.” Duke University Press, 2011.