12 Transformation and Liberation: Women in the Zapatista Army – Nick McGeveran

N. McGeveran

Transformation and Liberation: Women in the Zapatista Army

Introduction

On January 1st, 1994, the Zapatista army—a ski-mask clad rebel group thousands strong— declared war on the Mexican government. The Zapatistas (formally known as the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, or EZLN) had been brewing up a revolution in the jungle of the southern-most Mexican state of Chiapas for years. Ideologically, the EZLN is hard to definitively pin down—they are fighting against post-colonial neoliberalism, they believe in democracy, they want land reform and Indigenous rights. Importantly, the Zapatista Army had a high degree of participation from women, who played a crucial role in articulating its demands. In doing so, they created a new, transformative identity for themselves.

In this paper, I will draw on literature regarding the coloniality of gender, indigenous feminism, and identity formation to explore the way that Zapatista women have worked to change the gender system in their communities and the world. I focus on transformation as the primary source of analysis—although they have not created an entirely new world, they have transformed the gender relations within their communities and articulated a completely new identity for themselves. This identity is the Insurgenta, the “Zapatista Woman”. In short, it is an identity that makes transformation and liberation an essential element.

Chiapas, Mexico/Free World Maps

Coloniality, Feminism, and Project Identity

In María Lugones’ “The Coloniality of Gender”, she argues that gender (at least as we know it today) is inextricably tied to the colonial project. She uses Anibal Quijano’s framework of the coloniality of power as a starting point, expanding on the role of gender, as she believes his understanding is incomplete.[1] Lugones says that the relationship between the colonial gender system and the coloniality of power is one of “mutual constitution”[2], where gender was not a universally pre-existing system, but one created and manipulated by colonialism. The implementation of this system has been so effective that it seems like the natural order of things—it is telling that even Quijano, in an attempt to critique coloniality, reinforces the colonial gender system.

To demonstrate the imposed nature of the gender system, Lugones explains that the role of gender in many indigenous societies was very different. For example, some groups were matriarchal, or viewed gender in more expansive terms than the binary allows.[3] Colonization ended all of this, turning gender into a category that indicated subordination, not difference. Furthermore, the colonial gender system was heavily racialized. Lugones writes, “only white bourgeois women have consistently counted as women so described in the West.”[4] This is not to say that white bourgeois women do not also experience subordination due to patriarchy, but to point out that racialized women are not equally humanized, and thus do not reap the benefits of femininity that white women do. In short, the colonial system constructs gender differently along racial lines, and thus must be understood as thoroughly enmeshed with race.

Understanding that racialized gender oppression takes on different forms, it is not a stretch to understand that the fight of racialized women against subjugation must take on different forms as well. Feminism, as it is most commonly conceived, is a fight for the equality of women. However, this conception of feminism is also reductive, as it lumps the oppression of all women together. In response, feminists of color have articulated other feminisms that take difference into account—such as Indigenous feminisms. Explaining Indigenous feminisms, Luhui Whitebear writes, “The violences towards Indigenous bodies and lands are intertwined and part of the settler colonial paradigm. At its root, Indigenous feminism is about these connections as well as the ways in which settler colonialism has inflicted gendered violence on our bodies and spirits because of who we are as Indigenous people.”[5] Within Indigenous feminisms, dispossession and oppression are understood as intrinsically tied—therefore, they must be addressed together. Ultimately, “Indigenous feminisms offers a lens that helps us understand the role settler colonialism plays in cis-heteropatriarchal systems of oppression, including violence, that draws on Indigenous knowledge and experiences.”[6]

However, it is important to remember that “social movements must be understood in their own terms: namely, they are what they say they are.”[7] Applying the framework of feminism (and its accompanying assumptions) to groups who do not situate themselves within that framework reinforces colonial thinking. Clara Bellamy writes, “to judge [Zapatista women] from these parameters…is to fall into colonialist practices by affirming that they do not understand that they are feminists, but in reality—ours—they are.”[8] There are particularities within the experiences and worldview of Zapatista women that cannot be pigeonholed into an imposed framework—this is the idea of epistemic plurality that Sylvia Marcos suggests should frame discussions about Zapatista women and feminism. The Zapatistas are operating through a different conception of gender, of land, of the world, so it is crucial that we do not reinforce hegemonic colonial ways of thinking, and instead respect epistemic plurality.[9]

Nevertheless, Zapatista women share many goals with feminist movements, and the emergence of the EZLN and the creation of the Women’s Revolutionary Law was crucial to indigenous feminist organizing in Mexico.[10] Although the Zapatistas do not necessarily consider themselves feminists, the effects of the movement and its demands are at least parallel to it. In The Power of Identity, Manuel Castells’ wrestles with the issue of what he terms “practical feminism”. He asks whether “feminism can exist without a feminist consciousness”, which he recognizes is a difficult gray area, but concludes many women (like the Zapatistas) fight for feminist goals, particularly the “de/reconstruction of women’s identity.”[11] In this way, the Zapatistas might be practical feminists, and much of the literature about them is written from a feminist lens, so it doesn’t make sense to entirely do away with feminism as a framework.

However, since Zapatista women don’t fully align with feminism, other lenses are better fits. As a possible alternative, I use Castells 3 forms of identity formation: legitimizing identity, resistance identity, and project identity.[12] The first is used by the dominant culture to prop up and rationalize their dominance. The second is identity adopted by marginalized groups to endure oppression. The third is an identity which redefines societal positionality. Regarding project identity, Castells writes, “the building of identity is a project of a different life…expanding toward the transformation of society as the prolongation of this project of identity.”[13] For Zapatista women, transformation is the goal. Insofar as “Zapatista woman” is a category of its own, becoming a Zapatista woman requires radically redefining what womanhood means, and demanding that the rest of society adjusts. As the line of “feminism” and “not feminism” is porous and blurry, focusing on transformation avoids using other feminist movements, ideas, or assumptions as a benchmark, and gives Zapatista women space to define themselves.

Insurgentas: Women in the EZLN

On the same day that the EZLN declared war, they seized the San Cristóbal de las Casas, the capital of Chiapas.[14] Leading the charge was Major Ana María, a woman.[15] She was not the only one. Women permeated the structure of the EZLN, as commanders and as combatants, making up 30% of the Zapatista fighting force.[16] The EZLN was rather unique among analogous politico-military groups for this reason, as the (officially recognized) role that women play in combat is usually low.

However, this was not all. On the first day of the uprising, the EZLN released a set of laws, including the Women’s Revolutionary Law.[17] In this document, they lay out 10 demands regarding the treatment of women. By releasing the Women’s Revolutionary Law on the first day, the EZLN enshrined women’s issues as an important element of the uprising, not simply a side issue. Furthermore, the law was “not only a declaration to the government and the nation but also a demand to indigenous communities, whether Zapatista or not.”[18] To understand what this means, it is necessary to understand how the Women’s Revolutionary Law came about.

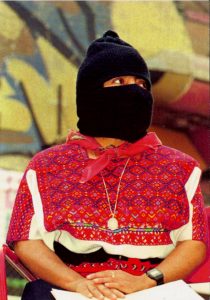

Zapatista Women / Waging Nonviolence

Isabel, a Zapatista commander, describes its genesis as the result of “talking, venting, analyzing. It’s not something from outside—it came from our own ideas, our own experiences in our families and communities.”[19] The Women’s Revolutionary Law, in this way, is deeply personal. It responds to the specific, intra-community issues that the Indigenous women of Chiapas faced, although it does so in an outwardly projecting way, as the demands of Zapatista women don’t stop at the transformation of their own communities. In 1993, following this process of deliberation amongst the women, the draft of the Revolutionary Law was presented to the Comité Clandestino Revolucionario Indígena (CCRI), the political body of the EZLN.[20] The men were nervous, but the women began to celebrate and clap, and the CCRI unanimously voted to pass the law. Describing the day, Subcomandante Marcos, an important military leader of the EZLN, said, “The EZLN’s first uprising was March 1993 and was led by Zapatista women. There were no casualties, and they won.”[21]

Prior to the rise of Zapatismo, women in Chiapas led restricted lives. Karen Kampwirth writes, “for a long time, probably hundreds of years, most Indigenous women of Chiapas lived under these conditions: heavily controlled by their fathers and husbands, often malnourished, always in danger of dying from minor complications in childbirth.”[22] Granted, the conditions that the primarily Mayan Indigenous groups of Chiapas faced were bad across the board—the region was intensely impoverished, 67% of people were malnourished, and economic and racial inequality was high.[23] However, for women it was worse, as different axes of oppression combined, both outside of and within their communities.

The passage of the Women’s Revolutionary Law did not immediately change this reality. Nonetheless, it opened the way for women to participate politically and militarily. In the opinion of many Zapatista women, it was their military participation (which was originally proposed because the Mexican army seemed less likely to fire on women) that marked the true turning point in their roles.[24] Fighting the Mexican military altered the women’s perception of themselves—as Celeste, a Zapatista woman, says, “the women found courage to defend ourselves and our communities. After that, women started to participate in other ways too, because we felt stronger.”[25] Furthermore, it served as a real-time rebuttal to the men dismissing the capability of Zapatista women, leading to a greater acceptance of women in military and political spaces. As a result, military participation was extremely important in actualizing the principles of the Women’s Revolutionary Law.

For the women who became full-time Zapatista fighters, the transformation was huge. They left their communities to go into the mountains, often living and training full time with the rest of the army.[26] This meant improved living conditions and large increases in the agency of individuals. These women fought alongside men, lived with them, and engaged with them, on much equal terms than before.[27] However, moving to the mountains was not without its problems. Women who did so were sometimes seen as “deserters” of traditional values, and it was difficult for women, particularly those with families, to leave.[28] Nonetheless, direct participation in the Zapatista army provided an avenue for a total reworking of identity and allowed women to adopt a new set of roles in their community.

Even so, the army was not the only component of the Zapatistas. Much of their strength was drawn from their intimate connection with the communities that supported them—the Zapatista villages that provided fighters, supplies, and support. These were autonomous villages who abided by the laws set forth by the EZLN, with their own education, health, and justice systems.[29] For the women in these villages, the transformative effect of Zapatismo was less obvious. While the Women’s Revolutionary Law provided some degree of legal protection, it did not guarantee compliance from men, particularly those who weren’t directly involved and were not steeped in its political culture.[30] The gains are also not complete from a material lens—to this day, Indigenous women in Chiapas account for 77% of all maternal mortality in Mexico.[31] Regardless, many women report cultural change outside of the EZLN proper, and while it may be slow and face structural roadblocks, Zapatista women continue to push for a better world both for themselves and their broader communities.

Furthermore, Zapatista women have sought transformative change outside of Chiapas, working with and inspiring many indigenous and feminist movements in Mexico and the world. In the years following 1994, the EZLN leveraged the visibility they had gained from the uprising to try and mobilize different sectors of Mexican society, holding events such as women’s conferences.[32] For some women, it was this organizing that helped form a new identity. Margarita, a Zapatista woman involved in the EZLN-hosted National Indian Congress, said, “it was the collective space of coming together that allowed us to clarify our consciousness as indigenous women and the profound historical knowledge of our pueblos.”[33] In these organizing spaces carved out by the Zapatistas, many indigenous women have been able to use each other as resources and support, giving additional life to the Zapatistas as an inspiration or catalyst for movements that succeeded it.

For all these groups— the individual Zapatista fighters, the women in Zapatista villages, and the Indigenous women of Mexico more broadly—the EZLN has forced a reckoning and redefinition of gender roles. It is by no means a “finished task”, and women in Chiapas are still faced with structural disadvantages and discrimination. Nevertheless, Zapatista women have carved out a new identity space. They have articulated their own positions on the role of women, meant to address the problems that they saw within their communities and the broader world. In all of this, from the genesis of the Women’s Revolutionary Law, to the post-’94 gatherings of women in Chiapas, women have led the way, banding together to re-cast themselves and push for transformation.

Women Who Give Birth to New Worlds: Transformation and Zapatista Women

Following the 2006 death of Comandanta Ramona, one of the most well-known Zapatista women, Subcomandante Marcos said, “the world has lost one of those women who gives birth to new worlds.”[34] These words serve as an excellent summation of the Zapatista project identity. While Marcos was referring to Ramona as an individual, the sentiment is applicable across the board. As a collective, the Zapatista women have articulated a set of demands that adds up to a reworking of the whole system they live under.

Comandanta Ramona/ Heriberto Rodriguez

To give birth to something new, there must be a before—the experience of the Indigenous women in Chiapas prior to 1994. The coloniality of gender is an important tool to understand this, as it demonstrates the insidious nature of colonialism. Not only did colonization, and its neoliberal successor states, wreak economic havoc on the Mayan people of Chiapas, they introduced ideas that caused communities to wreak havoc on each other. Forced early marriage, domestic partner violence, and male control over women’s actions were commonplace in the region, fueled by a culture of machismo.[35] Many of these ideas were not originally present in the Indigenous groups of Chiapas, where gender was seen in terms of balance and not domination.[36] As colonization reshaped the world, creating the coloniality of gender, Indigenous women were put into a multifaceted system of subordination, where Indigeneity and womanhood cannot be extracted from each other.

By participating in the Zapatista movement, Indigenous women were able to re-assert themselves as subjects. This doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing as it would under a Western feminist framework, as in the Zapatista worldview, “The other, male, be it a woman, son, mother, grandmother, is not outside themselves. The collectivity is part of itself.”[37] However, Zapatista women have undeniably worked to win agency for themselves, which is a direct affront to the colonial gender system that sees Indigenous women as the Other, sometimes to the point of complete dehumanization.

It is in this assertion of agency that Manuel Castells’ typology of project identity comes in. When the Zapatista women got together in sessions leading up to the 1993 meeting of the CCRI, they were engaging in the development of a project identity. The demands that they made—both explicitly in the Women’s Revolutionary Law, and in their actions—force a confrontation with the coloniality of gender. The Zapatista demand for agency is incompatible with the Othering of Indigenous Women, so something must give. Furthermore, many of their demands are intra-community in nature. While the particular problems of gender relations in Chiapas are strongly influenced by colonization, they remain problems that the Zapatistas solve internally. Looking both outward and inward, the women of the EZLN are constructing new identities upon demands for a radical reworking of gender relations.

While feminism does not necessarily have a place in the identity formation of Zapatista women as a collective—perspectives on this point are too varied to reach a definitive conclusion—the EZLN has been instrumental in the formation of an Indigenous feminist women’s consciousness.[38] In some ways, this is the new world they birthed. While Zapatismo was transformative for the individual women who engaged with it, and for the villages they live in, it has also been a transformative force within the world. The EZLN continues to hold women’s meetings, allowing them to participate themselves. However, they have also taken on a life of their own. The Zapatista women have emerged as figures representing Indigenous rebellion against patriarchy and neoliberalism in the imaginaries of many feminist movements, which has led to articulation of new and different project identities. While it is not one and the same, the Zapatista relationship with feminism is close, and Zapatista project identity has served as a model for later feminist groups.

Conclusion

By articulating themselves as Zapatistas, women in the EZLN radically reimagined gender and gender relations. I use the coloniality of gender to explain the post-colonial enmeshment of race, gender, and power, and Castells’ “project identity” to explain the transformation that took place because of the Zapatista women. They demanded change, both from their own communities, and from the world in general. This liberatory process allowed them to take up new positions in their day-to-day lives, inducing change that was both personal and cultural. Furthermore, they influenced latter-day groups, particularly feminist movements. While I began this paper intending to write about feminism within the Zapatista movement, I soon discovered that they didn’t necessarily identify that way, and to identify them as such ran the risk of reinforcing normative academic practices that see the scholar as the keeper of knowledge and Indigenous peoples as the unknowing Other. That doesn’t make feminism a useless lens, but prompts us to instead on the transformation that Zapatista women sought without passing judgement on it. Through their participation in the EZLN, Zapatista women have challenged the hegemony of colonialism and patriarchy, forming a project identity that calls for a new world.

Bibliography

Bellamy, Clara. “Insurgency, Land Rights, and Feminism: Zapatista Women Building Themselves as Political Subjects.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 10, no. 1 (2021): 86-109.

Blackwell, Maylei. “Weaving in the Spaces: Indigenous Women’s Organizing and the Politics of Scale in Mexico.” In Dissident Women: Gender and Cultural Politics in Chiapas. Edited by Shannon Speed, R. Aída Hernández Castillo, and Lynn Stephen, 115-154. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006.

Castells, Manuel. The Power of Identity. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Hernández Castillo, R. Aída. “The Emergence of Indigenous Feminism in Latin America.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35, no. 3 (2010): 539-545.

Kampwirth, Karen. “Also a Women’s Rebellion: The Rise of the Zapatista Army.” In Women and Guerilla Movements: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chiapas, Cuba, 83-115. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2002.

Klein, Hilary. Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press, 2015.

Lugones, María. “The Coloniality of Gender.” Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise 2, no. 2 (2008): 1-17.

Marcos, Sylvia. “Mexico: Reflections on the Struggle of Zapatista Women. Feminists?” Schools for Chiapas. December 6, 2022. https://schoolsforchiapas.org/mexico-reflections-on-the-struggles-of-zapatista-women-feminists/.

Millán Moncayo, Márgara. “Indigenous Women and Zapatismo: New Horizons of Visibility.” In Dissident Women: Gender and Cultural Politics in Chiapas, edited by Shannon Speed, R. Aída Hernández Castillo, and Lynn Stephen, 75-96. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006.

Morales, Yessica. “Indigenous Women in Chiapas Suffer 77% of Maternal Deaths in the Country.” Schools for Chiapas. January 10, 2023. https://schoolsforchiapas.org/indigenous-women-in-chiapas-suffer-77-of-maternal-deaths-in-the-country.

Rovira, Guiomar. Women of Maize: Indigenous Women and the Zapatista Rebellion. Translated by Anna Keene. London: Latin American Bureau, 2000.

Vidal, John. “Mexico’s Zapatista Rebels, 24 Years on and Defiant in Mountain Strongholds.” The Guardian (Manchester, UK), Feb. 17, 2018.

Weires, Gina. “The Impact of the Zapatista Movement on Women’s Rights in Chiapas, Mexico.” Clocks and Clouds 1, no. 1 (2012): 85-99.

Whitebear, Luhui. “Disrupting Systems of Oppression by Re-Centering Indigenous Feminisms.” In Persistance is Resistance: Celebrating 50 Years of Gender, Women, & Sexuality Studies, edited by Julie Shayne. Seattle: University of Washington Libraries, 2020. https://uw.pressbooks.pub/happy50thws/chapter/disrupting-systems-of-oppression-by-re-centering-indigenous-feminisms/

Citations

[1] María Lugones, “The Coloniality of Gender”, Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise 2, no. 2 (2008): 2.

[2] Lugones, 12.

[3] Lugones, 7.

[4] Lugones, 13.

[5] Luhui Whitebear, “Disrupting Systems of Oppression by Re-Centering Indigenous Feminisms,” in Persistance is Resistance: Celebrating 50 Years of Gender, Women, & Sexuality Studies, ed. Julie Shayne (Seattle: University of Washington Libraries, 2020), https://uw.pressbooks.pub/happy50thws/chapter/disrupting-systems-of-oppression-by-re-centering-indigenous-feminisms/.

[6] Whitebear.

[7] Manuel Castells, The Power of Identity (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 73.

[8] Clara Bellamy, “Insurgency, Land Rights, and Feminism: Zapatista Women Building Themselves as Political Subjects,” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 10, no. 1 (2021): 102.

[9] Sylvia Marcos, “Mexico: Reflections on the Struggle of Zapatista Women. Feminists?”, Schools for Chiapas, December 6, 2022, https://schoolsforchiapas.org/mexico-reflections-on-the-struggles-of-zapatista-women-feminists/.

[10] R. Aída Hernández Castillo, “The Emergence of Indigenous Feminism in Latin America”, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35, no. 3 (2010): 542.

[11] Castells, 259.

[12] Castells, 8.

[13] Castells, 10.

[14] Guiomar Rovira, Women of Maize: Indigenous Women and the Zapatista Rebellion, trans. Anna Keene (London: Latin American Bureau, 2000), 1.

[15] Karen Kampwirth, “Also a Women’s Rebellion: The Rise of the Zapatista Army” in Women and Guerilla Movements: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chiapas, Cuba (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2002), 83.

[16] Kampwirth, 90.

[17] Márgara Millán Moncayo, “Indigenous Women and Zapatismo: New Horizons of Visibility” in Dissident Women: Gender and Cultural Politics in Chiapas, ed. Shannon Speed, et al. (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006) 85.

[18] Millán Moncayo, 86.

[19] Hilary Klein, Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories, (New York, NY: Seven Stories Press, 2015), 73.

[20] Klein, 73.

[21] Klein, 74.

[22] Kampwirth, 89.

[23] Gina Weires, “The Impact of the Zapatista Movement on Women’s Rights in Chiapas, Mexico”, Clocks and Clouds 1, no. 1 (2012): 89.

[24] Klein, 118.

[25] Klein, 120.

[26] Weires, 88.

[27] Kampwirth, 102.

[28] Weires, 88.

[29] John Vidal, “Mexico’s Zapatista Rebels, 24 Years on and Defiant in Mountain Strongholds,” The Guardian (Manchester, UK), Feb. 17, 2018.

[30] Bellamy, 92.

[31] Yessica Morales, “Indigenous Women in Chiapas Suffer 77% of Maternal Deaths in the Country,” Schools for Chiapas, January 10, 2023, https://schoolsforchiapas.org/indigenous-women-in-chiapas-suffer-77-of-maternal-deaths-in-the-country.

[32] Maylei Blackwell, “Weaving in the Spaces: Indigenous Women’s Organizing and the Politics of Scale in Mexico” in Dissident Women: Gender and Cultural Politics in Chiapas, ed. Shannon Speed, et al. (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006), 129.

[33] Blackwell, 134.

[34] Klein, 144.

[35] Bellamy, 93.

[36] Marcos, “Mexico: Reflections on the Struggle of Zapatista Women. Feminists?”.

[37] Marcos, “Mexico: Reflections on the Struggle of Zapatista Women. Feminists?”.

[38] Hernández Castillo, “The Emergence of Indigenous Feminism in Latin America”, 543.