13 The Impacts of Spanish Colonialism on the Socioeconomic Status of the Indigenous Community in Mexico

The Impacts of Spanish Colonialism on the Socioeconomic Status of the Indigenous Community in Mexico

Introduction

Imagine living without access to clean water, electricity, or basic sanitation services. On top of this, there is over a 70% chance that you are living in poverty, and almost 30% chance that it is classified as extreme. This is the reality of the majority of the Indigenous community in Mexico, people who prospered on the land long before the Spaniards came in the 1500’s and colonized the country. Spanish colonization introduced and perpetuated an era of violence, mass killings of the Indigenous communities, and terrible illnesses. It also brought racism and discrimination towards the Indigenous people, and introduced the caste system, as well as the ideology of mestizaje, the mixing of races, as an attempt to make indigenous people have the white skin tone of the Spaniards. Racism and discrimination towards the Indigenous people have lasted to this day, with little improvement. This is because of the continued perpetuation of Indigenous hate and continued instatement of the racial hierarchy in Mexico, started by the Spanish, and later promoted by Mexican Revolutionaries and politicians throughout the years. In addition, the discrimination that women face in Mexican society causes an intersection of marginalization for Indigenous women, which will be discussed in this essay.

My argument is that Indigenous people suffer from discrimination and racism in Mexico and such racism impacts their education, access to health services, and access to work opportunities. Moreover, they experience other factors that negatively impact their standard of life, leading to higher rates of poverty and economic inequality. The discrimination they face stems from the caste system and mestizaje ideology that was implemented by the Spanish in the 1500’s, and then later promoted by Mexican Revolutionaries and politicians, further worsening discrimination and economic inequality for the Indigenous communities.

Background and History

In the 1500’s, the Spanish came to what is now called Mexico and began their colonial project in this part of Latin America, which had started in the Caribbean in 1492. This effectively created racism in Mexico, which had not existed prior. Anibal Quijano and Immanuel Wallerstein, scholars at the University of San Marcos and Binghamton University (SUNY) respectively, report that the Americas as a “geosocial construct” began in the 16th century (549). In their article, Americanity as a Concept, Quijano and Wallerstein argue that the New World order that was created consisted of four things all linked to each other: “coloniality, ethnicity, racism, and the concept of newness itself.” (550) The Spanish expressed this new world order in part in their caste system that created a racial hierarchy. According to Diana DiPaolo Loren, Senior Curator at Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, this caste system was based on the Spanish ideology of “limpieza de sangre” (purity of blood), which was used for both religion and race. The Spanish believed that those of Catholic and Spanish descent were superior to others (DiPaolo Loren). According to DiPaolo Loren, in the racial hierarchy, people of African descent were at the bottom of the social hierarchy, with Indigenous people slightly above them. In between Spanish and Indigenous people, “Individuals of mixed-blood ancestry were ranked accordingly — those with more Spanish blood were at the upper end of the scale, while those with more African or Native American blood tended towards the bottom of the scale” (DiPaolo Loren, 23). This system generated discrimination and inequality based on race in Mexico.

Another impactful part of Spanish colonialism in the New World was the implementation of mestizaje. Instead of enforcing segregation like their neighbors in the United States and Canada, the Spanish believed that the mixing of races with the goal to achieve the lightest skin color possible through reproduction with the Spanish race would be the best possible outcome. According to C. E. Marshall, scholar at the University of Ohio, Moscow, in his article The Birth of the Mestizo in New Spain, “Brought into intimate contact by religious zeal and economic interest, racial fusion of Spaniards and Indians was to a certain extent inevitable” (164). The Spanish were Catholic and wanted to assimilate the Indigenous people into Spanish civilization through religion. C.E. Marshall writes, “Spanish colonization impelled Spain to look upon the natives as beings to be converted and assimilated to Spanish civilization spiritually, culturally, and racially” (163). What’s more, the Spanish also needed laborers, and assimilation meant more people to work in harvesting natural goods for them (Marshall).

Another reason that mestizaje was promoted was that few women were brought from Spain to the New World. Marshall reports that by 1803, the number of “…European-born Spanish men in Mexico City outnumbered the European-born Spanish women ten to one…” (165). The Spanish government offered more favorable distribution of land to those in marriages, effectively guaranteeing that Spaniards would marry Indigenous women. (Marshall) The Spanish colonial project therefore combined the ideas that being Indigenous was the least desirable race, that society should value whiteness, and that indigenous people should intermarry in order to become white. Prejudice against Indigenous people in Mexico reinforced the racial hierarchy. Quijano and Wallerstein emphasize that coloniality “… continues in a form of socio-cultural hierarchy of European and non-European.” (550) In other words, a hierarchy that placed Europeans as superior to Indigenous people has endured in Mexico.

In fact, centuries later Mexican revolutionaries and politicians reified Mestizo racial identity as a part of political agendas. One example of this is Jose Vasconcelos’s La Raza Cosmica. Vasconcelos was a part of the Mexican Revolution and believed that the goal of the Revolution was to take a new path in Mexico, away from materialism and towards the “whole development of man” (XIV). Vasconcelos’ opinions on race were shockingly similar to that of the mestizaje ideology introduced by the Spanish. Jaén explains that Vasconcelos believed that with the mixing of races, one homogenous and superior race would emerge, taking only the best qualities of each race (Jaén, X). Once again, integration and assimilation of the Indigenous community would be “best” for Mexico. Moreover, he believed this would give Latin American countries an advantage over other countries, and even be beneficial for the development of mankind (Jaén). Jaén writes that many have criticized Vasconcelos’ Raza Cosmica ideology as racist because Vasconcelos is promoting the destruction of different races, which would effectively destroy Indigeneity in Mexico. Raza Cosmica encourages the loss of Indigenous cultures.

Vasconcelos is not the only Mexican who tried to use the idea of mestizaje as part of a political agenda. Just 20 years after Vasconcelos, in the 1940’s, Miguel Aleman, the president at the time, sought to incorporate the Indigenous community into society more fully through mestizaje. Anne Doremus, professor at the University of Washington, reports in Indigenism, Mestizaje, and National Identity in Mexico during the 1940’s and 1950’s that Alemán was aiming to solve the country’s economic problems, focusing on the overwhelming poverty that Indigenous people faced. Of course, this idea is illogical, as simply getting rid of Indigenous people and creating a homogenous race is not a viable option to truly supporting the Indigenous community. Furthermore, this ideology promotes the same erasure of Indigeneity and coloniality as those who came before him.

The idea of ending racism by ending different races of people was not limited to Mexico. At the beginning of the 20th century, Brazil was considered to be a country that was exemplary for the way they dealt with race. In the book The World is a Ghetto written by Howard Winant, an American political scientist, he discusses Brazil’s racial democracy myth. Brazil successfully gave the appearance that racism and discrimination in the country did not exist, suggesting the country had reached racial democracy successfully. However, Winant describes how, from the UNESCO studies in the 50’s and 60’s, “… the image of Brazil as a racial democracy has been attacked as a myth, as little more than a mask covering the face of widespread racial inequality, injustice, and prejudice…” (Winant, 220) This misconception surrounding Brazil and race was so deeply believed that UNESCO researched racial dynamics in Brazil after WWII in an attempt to see if it could be used as a model for other countries (Winant). However, their results quickly indicated that race played a structural role in almost every facet of Brazil’s social fabric. While UNESCO’s studies were mainly focused on economic inequality, the findings from their research opened up deeper analysis from sociologists in Brazil. Their research represented the first time that Brazil’s myth of racial democracy was challenged.

Brazil provides an interesting comparison point to Mexico, because it is very diverse. It was colonized by the Portuguese, who also introduced a large population of enslaved Black people (Winant). This country also had a high level of integration between races, similar to the Mestizaje in Mexico. However, it is clear that even when countries integrate deeply, racism and the effects of colonialism still play a big role in society, and do not disappear because of political promotion of a unified racial population. Winant describes how even though there are claims of racial democracy in the country, Afro-Brazilians still face discrimination, with higher rates of poverty, illiteracy, and lack of attendance in schools. In addition, Afro-Brazilians recently overcame the denied access to voting, and have little representation in elite circles of Brazilian society. Winant also describes the impacts on the daily life of all Brazilians: “Perhaps most important, the myth finds daily expression in the quotidian: Brazilian talk is permeated with racial discourse.” (220) Winant clarifies that even when it is ignored by politicians, race impacts everyone in society on a wide scale. Still, it can also be seen that political agendas that attempt to hide the issue of race can be very effective and widely adopted, as described by Winant in his explanation of national beliefs surrounding this myth.

Coloniality, or the legacy of colonialism, is another framework that can be applied when analyzing the current state of the Indigenous community in Mexico. Galeano describes the impacts of coloniality in Open Veins of Latin America. Galeano writes, “The Indians have suffered, and continue to suffer, the curse of their own wealth; that is the drama of all Latin America.” (59) Spanish colonialism was motivated by a desire to extract and take advantage of the abundance of natural resources in Mexico. Galeano describes business enterprises from the US as “a new procession of conquistadores” (61) who continue to take advantage of Native land and labor (Galeano). However, coloniality is present in domestic Mexican policies as well. Indigenous communities have been pushed into the most rural, poor areas; Galeano describes it as “Latin America’s native peoples were pushed into the poorest areas – arid mountains, the middle of deserts…” Coloniality offers a framework that connects the past to the present and makes connections between colonialism and today’s indigenous struggles; poverty, land loss and racism are all connected.

Poverty in Indigenous Communities

There is a shocking level of poverty in the Indigenous population in Mexico. CONEVAL found that in 2018 that 7 out of 10 Indigenous people live in poverty. Indigenous people have been pushed to rural areas, and around half of the Indigenous population lives in rural areas with access to fewer job opportunities other than manual labor, and little chance to improve jobs. While it is true that Mexico is a country that has high levels of poverty in general, it is clear that Indigenous people live in poverty at a rate highly disproportionate to their population size. For reference, around 1 out of every 4 Indigenous people in Mexico live in extreme poverty, a rate much greater than the average of 1 in 20 for the general population (CONEVAL, 2018). Poverty is especially detrimental to Indigenous women: In the same study by CONEVAL, findings indicate that as of 2018, around 80% of rural Indigenous women live in poverty, more than double the proportion of their nonindigenous urban male counterparts (35%). In addition, Mexican news outlet, El Economista reported that 9 out of 10 Indigenous women are at some form of socioeconomic vulnerability.

Class in Mexico

Social class is also connected to coloniality in Mexico, where in addition to racial hierarchies, there are class distinctions as well. In Alejandro Portes and Kelly Hoffman’s Latin American Class Structures, they describe the social classes in the region in 7 distinct groups: Capitalists, Executives, Elite Workers, Petty Bourgeoisie, Non-Manual Formal Proletariat, Manual Formal Proletariat, and the Informal Proletariat. Portes and Hoffman analyze class as a way to understand the “…long term strategic relations of power and conflict among social groups and the forms in which these struggles shape the relative life chances of their members.” (43) Applying this framework to Latin American social class divisions is very useful to analyze the economy and poverty levels in Mexico.

Most of Mexico’s population can be categorized in either the Manual Formal Proletariat (25.4%) or classified as an Informal Proletariat (45.7%). The proletariat in general is said to not be wholly involved in the fully monetized, legally regulated economy (Portes and Hoffman). The Manual Formal Proletariat are workers in industries, services, and agriculture, and are described as a class that “lacks access to means of production and has only its own labor to sell.” (Portes and Hoffman, 49) The Informal Proletariat is one step below, defined as workers who are not included in the modern capitalist sector, and must make a living off of unregulated employment or “…direct subsistence activities” (50). Even though Portes and Hoffman explain that the Informal Proletariat is around 45% of Mexico’s population, they also note that this class is growing. Portes and Hoffman note a lack of data that makes it difficult to have accurate numbers about social class. However, when analyzing income through a class-based framework, it is easy to see the vast income inequality in Mexico. Portes and Hoffman found that 75% of the employed population (which corresponds to the formal and informal proletariat) do not create enough income through their jobs to overcome poverty. In addition, they also described how members of the manual proletariat have, on average, levels of income at less than ¼ of the poverty line. While Portes and Hoffman do not discuss the impacts of Indigenous discrimination on poverty in the Mexican population, they provide relevant data on class distribution in Mexico, which allows us to contextualize the status of Indigenous groups.

Education and work for Indigenous people

An important factor that contributes to poverty and low-paying jobs for the Indigenous community is lack of formal education. In a study by CONEVAL on this topic, it was reported that 47% of the Indigenous population are behind on their education, which CONEVAL attributes to the fact that some Indigenous children do not go to school at all or, if they do attend school, it may not be proper formal education. Hence, even when Indigenous children do receive schooling, it does not always meet the state’s standards for education, subsequently excluding them from opportunities to attend higher education or getting the benefit of acquiring a formal degree, denying them jobs outside of that of the Proletariat.

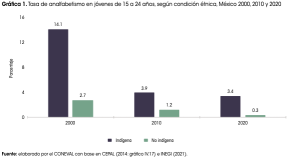

CONEVAL reports that the Indigenous population faces immense, unequal gaps in access to education when compared to the nonindigenous population. Even though the level of illiteracy overall was reduced in the last 20 years, rates in the Indigenous community are 11 times higher than that of the non-indigenous population which is attributed, in part, to having fewer years of schooling on average. What’s more, schools with a majority Indigenous population have less access to basic services necessary for learning such as connection to the internet, computers, and basic sanitary services like hand-washing stations, clean water, and clean electricity when compared to other schools with mainly non-indigenous students. In addition, only 17% of the Indigenous population attended schooling after high school, as of 2020. All of these factors contribute to less access to high quality education and make it harder for Indigenous people to secure higher paying jobs after completing school.

More importantly, education levels are connected to social class mobility, and the ability for indigenous people to lift themselves out of poverty. IGWIA reports that 43% of people who speak an Indigenous language in Mexico have manual, low skill jobs. This is nearly half of the Indigenous population, without accounting for those who are not employed, or do not receive regular forms of employment. Portes and Hoffman emphasize that lack of education makes it nearly impossible for an individual to attain a job higher than that of the proletariat. Without formal education, jobs other than heavy labor-intensive roles or service roles are very difficult to find. Because the income of laborers is not enough for a person to move out of poverty, Indigenous Mexican proletariats have no chance of reaching the minimum income required to be above the poverty line.

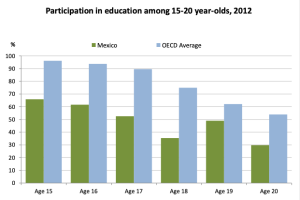

Poverty in Indigenous communities is a cycle, as children who grow up in poverty are less likely to be in an area with access to formal education, and are more likely to drop out in order to help provide for their family. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Mexico is the sole OECD country where 15–29 year-olds are expected to spend more time in employment than in education. 15 – 29 year-olds are expected to spend “6.4 years in employment and 5.3 years in education and training – one year more in employment than the OECD average (5.4 years) and two years less in education (the OECD average is 7.3 years)” (OECD 2). Drop-out rates are higher than any other OECD country, especially impacting those living in poverty, who need additional income quickly and drop out early to seek employment. Poverty limits life chances from generation to generation, and makes it extremely difficult for Indigenous individuals to move up in class or become stable economically (Portes and Hoffman).

Economic inequality is also related to structural racism and discrimination against Indigenous people. On a visit to Mexico, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People stated: “The information received during the visit indicates that indigenous peoples face huge challenges and particular obstacles for the effective enjoyment of their economic, social and cultural rights.” (1) In addition, she observed that over 55% of the Indigenous community lives in municipalities where they suffer from high rates of discrimination and marginalization. The aforementioned leads to lack of funding and support to the Indigenous community, as well as low quality access to education. Because coloniality continues the racism and discrimination introduced by the Spanish caste system in Mexico, as well as the continued promotion of racist ideas such as mestizaje in the 20th century all the way to the present day, it can also be connected to the economic inequality and marginalization towards Indigenous people.

In fact, direct racism causes Indigenous people to get fewer jobs than their non-Indigenous counterparts with the same qualifications. According to economist Ana Cañedo, it is very likely that racial discrimination is a factor that impacts employment. Cañedo discusses an experiment that was performed in Mexico in order to determine whether the wage gap could be explained wholly by the difference in education between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population. She found that this factor was not adequate in order to describe the wage gap, and therefore racial discrimination does play a role in economic inequality and the wage gap in Mexico. The data can conclude that both structural racism and the prejudices and racist ideologies that people within Mexico have internalized that contributes to the greater economic inequality that Indigenous people face.

Impacts of Gender Inequality on Economic Status for Indigenous Women:

Gender stereotypes and expectations for women impacts Indigenous and all women’s opportunities for economic success. For example, Indigenous women have higher rates of illiteracy in both rural and urban environments when compared to their male counterparts. Indigenous women attend less schooling on average, and as well as suffering more social discrimination as the main cause. This shows that the intersection of being Indigenous and a woman in Mexico results in more hardship, and that the structural discrimination both social groups face is significant.

As stated by Mexico’s Comision Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (National Committee of Human Rights) (CNDH) gender discrimination can be defined as:

“[…] toda distinción, exclusión o restricción basada en el sexo que tenga por objeto o por resultado menoscabar o anular el reconocimiento, goce o ejercicio por la mujer, independientemente de su estado civil, sobre la base de la igualdad del hombres y la mujer, de los derechos humanos y las libertades fundamentales en las esferas política, económica, social, cultural y civil o en cualquier otra esfera.”

(Any distinction, exclusion, or restriction based on sex that has the objective or result of diminishing or disallowing the recognition, possession, or exercise of rights by women, independent of marital status, on the basis of equality between men and women, human rights, basic liberties in politics, economics, social status, cultural, civil, or any other aspects.)

Gender discrimination is acknowledged as an important problem in Mexican society. Indigenous women, who face both gender and racial discrimination, experience the impact of the intersectionality of both of these forms of discrimination. Similarly, in Afro-Cuban Cyberfeminism: Love/Sexual Revolution in Sandra Álvarez Ramírez’s Blogging, Sierra Rivera describes the intersectionality of the Afro-Cubana struggle: “… socioeconomic success and failure in contemporary Cuba are gendered and colored: the profile of the winner, or the true revolutionary, is “un hombre más bien joven, con calificación media y alta, blanco y preferentemente de origen social colocado en grupos de técnicos, intelectuales, directivos’ (a younger man, middle to upper class, white, and preferably from a technical, intellectual, or managerial background)” (335). Similarly in Mexico, a country with both gender and racial inequality, non-indigenous men find it easier to succeed economically. Thus, it is important to recognize that in addition to the profound discrimination that Indigenous people in Mexico face, the analysis of discrimination through a feminist lens highlights the intersectionality of both racism and sexism.

The term intersectionality was coined by in 1989. She first used it to analyze the unique discrimination that Black women faced in employment. In a video for Southbank center, Crenshaw states, “Specifically, black jobs were available to black who were men, and women jobs were available to women who were white. Black women, who were blacks who were not men and women who were not white, were unable to be hired in many of these industries because they didn’t fit the kind of woman or the kind of black that was looked for by the employer.” Thus, the term intersectionality helps to highlight the failures in addressing discrimination when more than one kind of injustice is at play, and can also be extended in the analysis of gender-based violence.

While many efforts have been made by the Mexican government to improve the state of gender inequality, discrimination against women is still a pressing issue. One important dimension of the victimization of women is through domestic violence and femicide. According to ONU Mujeres, violence against women:

“Es una forma de discriminación que impide su acceso a oportunidades, socava el ejercicio de sus derechos fundamentales y tiene consecuencias en la salud, la libertad, la seguridad y la vida de las mujeres y las niñas, así como un impacto en el desarrollo de los países y lastima a la sociedad en su conjunto”

(…Is a form of discrimination that prevents their access to opportunities, undermines the exercise of their fundamental human rights, and has consequences on their health, freedom, safety, and the lives of women and girls, therefore impacting the development of countries and hurting the whole society)

In a Harvard International review, Madison Eagan reports that Indigenous women are especially harmed by femicide and violence due to already being in a vulnerable state from their economic and social state: living in poverty and having limited access to resources such as healthcare or ability to report to police makes violence against Indigenous women especially common, with little consequences to the perpetrators. When applying the framework of intersectionality, it is clear that the alarmingly high levels of violence against Indigenous women are due to the failure of addressing the intersectionality between racism and sexism in the country. It is clear that with such high rates of violence against Indigenous women, these forces of coloniality limit the possibility for equality in regards to racism, sexism, and classism.

Conclusion

The colonization of the Indigenous people by the Spanish and their introduction of the racial hierarchy through the caste system and mestizaje has led to long-lasting coloniality in the forms of a persistent legacy of colonialism in the form of structural racism and discrimination in the region. In the case of Mexico,there are enduring and dramatically higher levels of poverty for Indigenous people. When the Spanish colonized the Americas, they created a new World order, effectively creating racism in Latin America. This led to ongoing and long-lasting discrimination, creating the belief that indigeneity should be replaced with mestizaje, stemming from the Caste system created by the Spanish, which encouraged reproduction with white Spaniards in order to have children with a lighter complexion.

The ideology of the Spanish was carried on and promoted by many Mexican politicians such as Vasconcelos during the Mexican Revolution. These racist ideas have effectively propelled coloniality long past the days of the Spanish colonization, and have led to the continued perpetuation of discrimination against the Indigenous community in Mexico and the rest of Latin America. This has led to fewer opportunities for education, which in turn have led to fewer options to attain high paying jobs, leaving indigenous Mexicans in the proletariat class. Limited opportunities, in turn create a vicious cycle, limiting chances to get out of poverty. Moreover, Indigenous women suffer from the intersectionality of both gender and racial discrimination. Indigenous women suffer from high rates of violence and femicide, and struggle in attaining jobs due to prejudice in society. Therefore, it can be concluded that the effects of Spanish colonialism can be seen in the current socioeconomic status of 21st century Indigenous communities in Mexico, and that the overwhelming rates of poverty in the Mexican Indigenous community can be partly attributed to the longstanding structural racism and discrimination that they face daily as a result.

References

“9 de cada 10 mujeres indígenas sufren vulnerabilidad socioeconómica en México.” El Economista, https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/9-de-cada-10-mujeres-indigenas-sufren-vulnerabilidad-socioeconomica-en-Mexico-20230826-0001.html. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

Canedo, Ana. Bridging the Indigenous Wage Gap in Mexico. Cornell Policy Review.

CNDH. Conceptos Que Debes Conocer – CNDH. https://uig.cndh.org.mx/inicio/conceptos. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

CONEVAL. “CONEVAL Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de La Política de Desarrollo Social | CONEVAL.” Multidimensional Measurement of Poverty in Mexico: An Economic Wellbeing and Social Rights Approach, 22 Oct. 2023, https://www.coneval.org.mx/Paginas/principal.aspx.

—. Educación Para La Poblacion Indigena en Mexico: Un Derecho a Una Educación Intercultural y Bilingue. 2022, p. 95.

—. “La Pobreza En La Población Indígena de México, 2008 – 2018.” CONEVAL, https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/MP/Documents/Pobreza_Poblacion_indigena_2008-2018.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct. 2023.

DelVal, Jose, et al. El Mundo Indígena 2020: México – IWGIA – International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. https://www.iwgia.org/es/mexico/3745-mi-2020-mexico.html. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

Doremus, Anne. “Indigenism, Mestizaje, and National Identity in Mexico during the 1940s and the 1950s.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, vol. 17, no. 2, 2001, pp. 375–402. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/msem.2001.17.2.375.

Eagan, Madison. “Indigenous Women: The Invisible Victims of Femicide in Mexico.” Harvard International Review, 30 Nov. 2020, https://hir.harvard.edu/indigenous-women-victims-of-femicide-in-mexico/.

Figueroa, Monica. “Blacks, Mestizos, and Mestizaje: The Complex Backstory.” Mexico Solidarity Project, https://mexicosolidarityproject.org/voices/61/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

Galeano, Eduardo. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. 25th anniversary ed, Monthly Review Press, 1997.

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Intersectionality and Gender Equality. Directed by Southbank Centre, 2016. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DW4HLgYPlA.

Loren, Diana DiPaolo. “Corporeal Concerns: Eighteenth-Century Casta Paintings and Colonial Bodies in Spanish Texas.” Historical Archaeology, vol. 41, no. 1, 2007, pp. 23–36.

Marshall, C. E. “The Birth of the Mestizo in New Spain.” The Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 19, no. 2, 1939, pp. 161–84. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2507440.

OECD. Country Note: Education at a Glance Mexico 2014. 2014, p. 11, https://www.oecd.org/education/Mexico-EAG2014-Country-Note.pdf.

Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. “End of Mission Statement by the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on Her Mission to Mexico.” OHCHR, https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2017/11/end-mission-statement-special-rapporteur-rights-indigenous-peoples-her-mission. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

ONU Mujeres. “La violencia feminicida en México: Aproximaciones y tendencias.” – ONU Mujeres, México, https://mexico.unwomen.org/es/digiteca/publicaciones/2020-nuevo/diciembre-2020/violencia-feminicida. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

Portes, Alejandro, and Kelly Hoffman. “Latin American Class Structures: Their Composition and Change during the Neoliberal Era.” Latin American Research Review, vol. 38, no. 1, 2003, pp. 41–82. primo.lib.umn.edu, https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2003.0011.

Ramos, Liliana Gómez Flores, and Sergio Meneses Navarro. “The Health of Indigenous Populations in Mexico: Disencounters.” ReVista, 9 May 2023, https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/the-health-of-indigenous-populations-in-mexico-disencounters/.

Saavedra, Diana. 500 años de pobreza y marginación indígena – UNAM Global. 12 Oct. 2022, https://unamglobal.unam.mx/global_revista/500-anos-de-pobreza-y-marginacion-indigena/.

Sandoval-Forero, Eduardo Andrés, and B. Jaciel Montoya-Arce. “Indigenous Education in the State of Mexico.” Papeles de Población, vol. 19, no. 75, Mar. 2013, pp. 239–66

Vasconcelos, José, and Didier Tisdel Jaén. The Cosmic Race: A Bilingual Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Winant, Howard. The World Is a Ghetto : Race and Democracy since World War II. New York :Basic Books, 2001.