3 The Impact of Musical Martyrs: The Legacy of Victor Jara

mlsb2022

Introduction

The transformative impact of music as a catalyst for emotional and intellectual reflection transcends cultural and geographical boundaries. In fact, its ability to elicit specific feelings is so renowned that it is organized into playlists for this purpose. Therefore, music became the vessel through which people immortalize their surroundings and subsequent emotions. The first love song/poem dates back to 2500 BCE. Musicians incorporate vintage film monologues into their tracks because the message remains true. They sing songs about newborns and the dead alike because the human experience is not individual but has been repeated and fossilized over and over. There is a genre, artist, or song for situations ranging from weddings to funerals to revolutions. The last contains songs recognized for their intention to create social change, called “protest songs,” including the protest musical movement Nueva Cancion created in Chile when mixed with Chilean folk.

Many academics have analyzed this movement for its social, political, and religious impact on Latin America, with an emphasis on its role prior to the 1973 Chilean coup d’etat that put Augusto Pinochet in charge. How did a genre of music that began as a folk revival with a focus on projecting the voices of elders forgotten in shantytowns become synonymous with the Communist Party and the late Salvador Allende? My research dives into the rise of Victor Jara, a former member of the folk group Cuncumen, to the namesake of a stadium in Santiago, which could only be completed after acknowledging and discarding the west-centric lens that is often defaulted to, as described by the readings we did in class. Additionally, our theoretical framework allows for the analysis of Jara’s role in bolstering the left to be contextualized by Latin American colonial and oppressive history. Further research later in the paper is devoted to discovering what role the political life of an artist has in determining their impact or legacy.

Theoretical Framework

Miner and Latin American History

Our in-class analysis of Body Ritual Among the Nacirema by Horace Miner demonstrated the coloniality of knowledge by examining a fake tribe through a lens of Western superiority and civilization. The passage highlights how people from globally dominant countries view other cultures and the language used to describe them by allowing the readers to examine their own nation through this crucifying lens, as “Nacirema,” which spelled backward, means America. The language chosen by Miner not only carries an underlying tone of disgust but also tends to lean toward scientific terms, repeatedly referring to women as female (Miner 56) to create a distinction between our civilized human world and their animalistic underdeveloped one. This perception of the Nacirema as barbaric is an example of coloniality (the legacy of colonialism) as it supposedly reflects Miner’s beliefs, and he is not genuinely interacting with or altering the civilization.

Our conversations later in the semester about coloniality versus colonialism established that coloniality persists long after the act of colonization has ended. However, from the viewpoint of Miner in this passage, the nation has remained untouched until this point, arguing that the enduring legacy of coloniality also sets the stage for colonization, creating a vicious cycle. In unearthing this, we begin to understand the importance of decolonizing our knowledge to protect the diverse cultures of Latin America.

Galeano’s Exploration of Latin America

The first section of Eduardo Galeano’s book, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, goes over the ‘discovery’ of the region and introduces us to the exploitation that started in the 1500s and continues to this day. He paints the arrival of the conquistadors in vivid detail, an era of genocide and extraction of natural resources with devastating impact on the indigenous populations subjected to forced labor, displacement, and death, all to facilitate their own rape. In his introduction, Galeano explains how these continual defeats suffered by what is now Latin America led to its underdevelopment (truthfully actualized by European and Western powers) and played an integral role in developing the world’s capitalist structure (Galeano, 2). However, what is most interesting is given to us by Isabel Allende’s forward section, where she, too, paints a vivid picture of the author himself. She notes that throughout his life, he had been displaced twice and lived in exile for a total of 11 years and that during this time he traversed the region and spoke to people of all classes, races, and circumstances. Despite seeing the full range of humanity and being himself subjected to the darker side, he is an optimist. Allende’s fascination with this is that it does not come from a place of naivety but rather is a learned and unwavering stance, memorialized in his own words: “However much death may come, however, much blood may flow, the music will dance men and women as long as the air breaths them and the land plows and loves them” (Galeano, Memory of Fire, 199).

The House of Spirits

Another reading we will use to examine Chile’s Nueva Cancion we look at is Isabelle Allende’s writings, specifically chapter 4 of The House of the Spirits, which mainly follows the Trueba family as they venture out into the country (and then back). While he is not the main focus of this storyline, we get introduced to Pedro Tercero Garcia very early on. He is the malnourished child of Pedro Segundo, the unofficial keeper of the family home out in Tres Marias, and the depiction of Chilean activist and musician Victor Jara. Although the child grows up in poverty, he befriends Blanca, the Trueba family’s youngest member and a member of a wildly different social class. Despite his proximity to the oppressors, Pedro Tercero still immerses himself in rebel ideology and listens intently to his grandfather’s stories about their traditions and cultural superstitions. His resistance is not quiet either, being the only character to stand up to Esteban Trueba despite the beating he takes for sharing his communist beliefs. All this, however, is just a prequel to the transformation that begins to take place at the end of the chapter after he hears the story of the hens and the fox. The metaphor for revolution is clear, and unlike Blanca, who scoffs at the idea that something as docile as a hen could ever overpower a fox -– Tercero, in true Jara fashion, sears the elder’s story into his memory and begins to understand how impactful sheer number and unity can be.

The Art is Fueling Protests in latin America

Although Nueva Cancion had a vibrant and influential life in the 1960s and 70s, it is evident from the executive director of the Leslie Lohman Museum in New York, Alyssa Nitchun’s, coverage of the modern protest movement that the meaning behind those songs has not wavered. In her article for ‘The Art Newspaper’ titled The Art is Fueling Protests in Latin America, she mentions how the reason the military dictatorships that once engulfed Latin America paved the way for artist expression in protest. This is due to the violent nature of these regimes and how the safest way to get the messages to the maximum number of people without anyone going missing was through voice. What is most interesting about this article is that it presents the same concept. With modern media, protest songs take on a new look as they can be shared, rewatched, and memorized much faster while still reaching all corners of the globe. She notes that this time around, artists are still found leading protests, and they describe their use of classic protest songs and other traditions as an “intersectional twist”. While we might be examining history when we look into Nueva Cancion, Nitchun shows us that 50 years later, Victor Jara’s angelic voice remains the face of revolutions and continues to empower people to stand for their people long after his death.

The Case

Violeta Parra – The Mother of Nueva Cancion

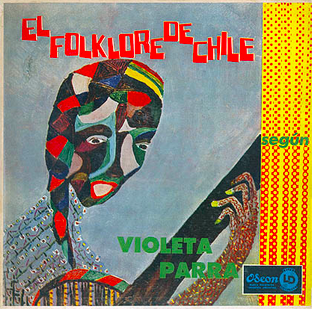

In 1952, a Chilean Singer by the name of Violeta Parra separated from her sister and their musical duo by the name “Las Hermanas Parra” to begin her folklore journey. She got her hands on a tape recorder and began seeking the traditional folk songs from the elders who still resided in the Chilean shantytowns (Cerda). Through painstaking devotion, she was able to piece together full folk songs (particularly part of the tradition el canto a lo poeta, a Chilean style of poetry) and become a staple of Chilean folk hi

story, having saved over 3000 traditional pieces during an era of erasure (Verba 154). In 1954, she starred in a year-long radio show, Asi Canta Violeta Parra, which gained traction quickly and effectively reintroduced Chileans to the rich culture and history she had thatched together by sharing her interviews with elders, folk tales, and traditional medicine (Parra 43).

The growth of the Nueva Cancion movement began here with her sharing and bolstering the cultural traditions of Chile. However, the revolutionaries soon took it over, and it blossomed into a method for people to voice national concern through a classic style. Many blended the works of Parra with famous Cuban artists (Tumas-Serna 143), such as Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés, whose main messages were rooted in protest rather than their nation’s history. What becomes of this is a unique sub-genre of traditional style resistance songs, where there is controversy over whether it should constitute pop music due to its drastic influence over other art of the era and because its inspirations stem from well-known songs or if it should retain its rural label as the original concept intended to be a return to Chilean roots (Moore 180).

Chilean Politics 1965-1975

In the 1960s, socialist and communist political movements were on the rise in Chile (much to the dissent of the US), and their members supported the Frente de Accion Popular (FRAP), the left-wing party. In 1969, the Unidad Popular (UP) was established as its successor, comprising the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, the Radical Party, the Social Democrat Party, MAPU, and API, with their candidate Salvador Allende’s campaign promoting a peaceful transition to socialism and winning the 1970 presidential election (Farnsworth 4). On September 11th, 1973, there was a US-backed coup that replaced him with fascist dictator Augusto Pinochet, who would rule from 1973-1990 (Wilkinson). A principal advocate for the UP and a pivotal figure for the movement was Victor Jara, a musician and revolutionary rolled into one whose songs often urged the working lower class to stand against the injustices they faced. His lyrics called for complete reform of the Chilean life structure, including land redistribution (away from foreign/US control and toward the residents) and investing in people’s education and health (Taffet).

Victor Jara

In 1957, Violeta Parra met a fellow Chilean artist, Victor Jara, who eventually picked up on her traditional style and lyrical love for all the people of Chile. Following her death in 1967, he became the new face of the movement whose lyrics called for a complete reform of the Chilean government and society – including land distribution away from foreign (mainly US) capital and toward Chilean residents alongside a reorientation/refocus on the peoples’ education and health (Taffet).

As his songs grew in popularity, he became aligned with the UP. Although he was a musician, he played a pivotal role in the success of the Allende campaign by associating his voice with the party and even transforming Caludio Ittura’s lyrics of Venceremos to make it the campaign’s theme song (Andrew). In the eyes of the people, one could argue that Allende was not the true leader of the political left but rather that that title belonged to Jara as he had just as much, if not more, political influence through his songs. This was not lost on Pinochet’s officers, who, on September 12th (the day following the coup d’etat), rounded up 6,000 political prisoners at the Santiago Boxing Stadium, where they recognized Jara immediately and separated him from the others. Over the next four days, he was publicly tortured (while he defiantly sang Venceremos) on stage and ultimately murdered in front of the crowd, after which they strung his body up on the outside of the stadium in an attempt to disgrace his reputation (Tyler).

Jara’s Discography

When he was starting, Jara served as the artistic director of Cuncumén, a folk group that sang mainly reassembled or recently found Chilean songs (Zamorano). After ten years, he ventured out and dropped his first solo album, “Victor Jara,” in 1966, taking the folkinfluences and noting (translated from Spanish) that “I am increasingly moved by what happens around me. The poverty of my own country, of Latin America and of other countries in the world”. His first solo genre falls under the category of Nueva Cancion due to its political messaging. Notably, his musical group had evolved from purely folk, but he left because their style was ultimately too limiting for all he had to say (Bade).

In 1966, he released a collaboration with Quilapayún, a prominent musical group in Nueva Cancion committed to political expression, to release a compilation of Chilean Folk songs under the title Canciones Folklóricas de América (Leiva). By 1969, Jara’s music was becoming entwined with the communist movement and the UP releasing Pongo a tus Manos Abiertas, in which he partnered with them again to create “Plegaria a un Labrador.” This song, “Prayer to a Worker,” was viewed as a call to the peasants and won the first Festival de la Nueva Canción. In 1970, he released Canto Libre and rewrote Sergio Ortega’s Venceremos to mention Unidad Popular and Allende to serve as the campaign anthem. In 1971, he released El Derecho de Vivir en Paz as a protest album in response to the Vietnam War and as a tribute to Ho Chi Ming, the leader of the Vietnamese Communist Party (Simon). In 1972, he put out La Poblaión, containing nine songs highlighting the struggles of poor people living in shanty towns near Santiago, the capital (Gatehouse). His final album, Manifiesto, was released posthumously in 1974 with lyrics equally haunting in English, “the song makes sense when it throbs in the veins of the one who will die singing the truthful truths” (Wiser).

Analysis

Folk Roots

Victor Jara’s discography highlights his evolution from folk singer to political activist to one of the most essential martyrs in Chile’s history. His introduction to Parra in 1957 was his introduction to Chilean folk, after which he joined Cuncumén for their theatrical elements and to explore the recently reassembled Chilean folk songbook (Moss).

Although there was a general folk revival throughout the globe in the 1960s, this Chilean song movement is distinct in that “it implicates a group of singer-songwriters and musicians of a like mind working to advance a shared cause, in this instance, the recovery and preservation of Chilean identity through song” (Dubec 21). This genre came from a more considerable Latin pushback against US-centric beliefs, as the world was increasingly aware of the normalization and idolization of the West. Miner also outlines the normalization of this Western lens through his Nacirema piece, which took a magnifying glass to this theoretical tribe. In revealing that the writing is actually about America, he emphasizes the danger of looking at history in a vacuum, as without context, one often jumps to their own conclusion.

Nueva Cancion as a Genre

The 1960s-70s was a global era of social movements, and the sentiments behind Nueva Cancion were not formed from thin air but rather emerged from shared experiences with the US. When it comes to actually breaking down songs that fall in this genre, it is clear that what connects all these voices is a distinct pan-Latin style in conjunction with sentimental lyricism. (Tumas-Sernas 140). This blended stylistic element essentially means using techniques or instruments from one’s home country alongside popular US styles that were experiencing a Rock revival to create a new sound that brings popular culture back to the homeland. Partnering this with lyrics that either criticize foreign occupation or broadcast their injustices highlights an interlinking web connecting a country’s members that can be seen by and influence neighboring nations. This allows the artists and listeners alike to enjoy a sense of community among Latin countries, which helps push back on the suffocating power of US-centric ideals and values in their home countries.

Champion of Nueva Canción

The first significant shift followed Jara’s launch into the solo industry, where he retained his folk roots but, after Parra’s death, fully embraced the political distinctions that made music Nueva Cancion. With the release of “Plegaria a un Labrador,” he really established himself as the face of the movement by winning the first-ever festival of that genre. The lyrics of the song call for liberation from those ‘who dominate us in misery” in line 9, immediately preceding the chorus (lines 9-16), where the prayer of the song takes place, noting “ … changes in dynamics, timbral quality, tempo, and musical texture combining to create an overall impression of progressive urgency” (Dubuc, 98). Theologians, musicians, and political scientists alike analyzed this song for its impact on the socialist movement. Even Isabel Allende’s tale about the Hens and the Fox in The House of Spirits (157) immortalizes the impact of the genre.

“One day the old man Pedro García told Blanca and Pedro Tercero the story of the hens who were forced to confront a fox who came into the chicken coop every night to steal eggs and eat the baby chicks […]

Blanca laughed at the story and said it was impossible because herns were born stupid and weak and foxes are more astute and strong, but Pedro Terceco did not laugh”

The folktale demonstrates the difference in mentality surrounding revolutionaries. Society tells us that revolutionaries are great, almost inhumane in their goodness and ability to sacrifice, and that there is a big difference between a regular person and a revolutionary. This, coupled with the offensive yet common rhetoric of the poor as inherently stupid and genetically inferior to the wealthy, leaves the people feeling hopeless for change. Then comes a folk revival that emphasizes the importance of indigenous Chilean communities and traditions, and much like the impact of the old man’s story’s impact on Pedro Tercero, this tendril of unity sparks something in Jara. He proceeds to put the heart of the story that moved him in each of his songs and begins moving the people. The folktale is an allegory for Jara’s ability to garner support for the UP, beginning with his Call to Action to the Peasants of Chile, demonstrating the power of the masses, or hens.

Posthumous Album Release

Jara’s album Manifesto dropped a year after his death using his unfinished songs with accompaniment from Chilean group Inti-Illimani and musician Patricio Castillo (Warner Music Chile). This decision feels dangerous, especially considering the military targeted Jara as a political prisoner precisely because of his music. Although it feels surprising, it begins to make sense when you reintroduce Galeano’s observations that highlight how the strengths and resilience of Latin Americans are often revealed in music. Jara’s music gave a voice to the poor with lyrics describing the land corruption in detail, telling stories where oppressors inevitably fall, and emphasizing everyone’s inalienable right to live. The divisive release of this album demonstrates that not only was he telling the people’s stories, but in romanticizing the Chilean working class, he gave them a sense of dignity and hope that they needed to be reminded of as they plunged into the dictatorship. Galeaonos argues this quality after having experienced all parts of Latin America, so there is weight when he notes that despite all the genocide and cover-ups, the people will continue to sing. In this, we realize that those who put a voice behind his last album recognized the immortality of the song. While he may not be able to impact the current situation or stop the Pinochet regime, Jara’s words still hold Chile’s pain. They will inevitably serve as evidence and support the next time the country’s poor mobilize.

Derecho de Vivir en Paz

Written in 1971, Derecho de Vivir en Paz was a Jara hit from the jump, but following his public assassination by the Chilean Military under the Pinochet dictatorship and their following imprisonment of Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, it cemented its place in the hall of fame (Simon and Wharton). The anti-Vietnam War lyrics send strength and encouragement to fellow people, validating their right to live in peace and that the nation will prevail despite the devastation. While these words are pointed with the specific mention of Vietnam and Ho Chi Minh, the general sentiment of perseverance in lyrics is a common need when the tides begin to shift:

Lyrics of Derecho de Vivir en Paz by Victor Jara “Tío Ho, nuestra canción

Es fuego de puro amor

Es palomo palomar

Olivo del olivar

Es el canto universal

Cadena que hará triunfar

El derecho de vivir en paz”

“Uncle Ho, our song

It is fire of pure love

It’s palomo palomar

olive tree from the olive grove

It is the universal song

Chain that will make you successful

The right to live in peace”

From the beginning of this except, Jara addresses Ho Chi Minh as “tio,” which directly translates to uncle but in Latin culture is a common term for loved ones and friends. In using a familiar term to address this other political figure, Jara is announcing to the world that they are united in this fight for communism. He further emphasizes this point by saying directly in the song that while it is dedicated to the Vietnamese movement, the cause is universal, and everyone gets to live in peace.

Following Galeano’s previous point regarding the timelessness of music, this song became a central aspect of the anti-government demonstrations in Chile on October 25, 2019, as described by Nitchun’s article. Thousands of people swamped the streets to sing a song that, through a linguistic lens, condemns a war they have no connection to. This is because by this point, Jara had stopped being a Chilean singer and had transformed into a standard symbol of resistance that was able to help Chilean and Vietnamese protestors back in the 70s – and their children now.

Conclusion

This paper into Victor Jara’s role as a musical martyr vividly demonstrated the importance of resistance music for societal change. This media is not just a form of entertainment but serves as a time capsule capable of documenting emotions, stories, and the human experience across centuries. Nueva Canción, born from Chilean folk and political unrest, emerges from these truths and begins amplifying the voices of overlooked elders. Their narratives and history begin to join the people of Chile, calling for the working class to unite and fight for social change. Victor Jara’s discography then demonstrates how the folk roots stimulate a recognition of the government’s injustice and facilitate a common identity to give strength to the pushback.

Dissecting the literature prior to investigating Jara’s story instills in the readers a sense of the internal biases and prejudice that come from the coloniality of knowledge, simultaneously demonstrating the need to decolonize perceptions to safeguard the diversity of Latin America. This erasure is emphasized by the vivid accounts painted in Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America, whereas Allende’s House of Spirits reveals the spirit in need of protection through her depiction of Pedro Tercero Garcia.

Jara’s evolution from being a musician to becoming a global emblem of resistance stems from his songs being not just melodies; they were anthems for reform that echoed the struggles of the marginalized. The publicly tragic end of his life, his unwavering defiance despite brutal torture, and the symbolism of his posthumous album, ‘Manifiesto,” underscores the enduring legacy of his music. There is a song released in every stage of his evolution that resonates with someone’s story not solely because of his skills as a musician and lyricist but because he focused on the reality of the people who often share similar stories as their ancestors. For this, Victor Jara’s narrative transcends time. It showcases how music, through its lyrical truths and emotional resonance, becomes a timeless beacon of hope and resistance – inspiring generations to stand against oppression and fight for a better world.

References

Allende, Isabel 1985. The House of the Spirits. 1st American ed, A.A. Knopf.

Angell, Alan. Feb. 1972 “Allende’s First Year in Chile.” Current History (Pre-1986), vol. 62, no. 000366, p. 76.

Bade, Gabriella. “Víctor Jara.” Víctor Jara | MusicaPopular.Cl, http://www.musicapopular.cl/artista/victor-jara/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

Bello, Walden. 11 Sept. 2023 “Remembering Salvador Allende and the Chilean Counterrevolution.” Foreign Policy in Focus, Inter-Hemispheric Resource Center Press, p. 1. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/pais/docview/2864646298/abstract/97110CAC13A44B8PQ/2.

Dubuc, Tamar. 2008. Uncovering the Subject Dimension of the Musical Artifact: Reconsiderations on Nueva Cancion Chilena (New Chilean Song) as Practiced by Victor Jara. University of Ottawa (Canada), Thesis. ruor.uottawa.ca, https://doi.org/10.20381/ruor-18807.

Eliser. Venceremos – Everything2.Com. https://everything2.com/title/Venceremos. Accessed 5 Dec. 2023.

Farnsworth, Elizabeth, and Marc Herold. Mar. 1971 “Popular Unity Government:Basic Program.” NACLA Newsletter, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 3–17. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.1971.11724265.

Fortes, Irene. INTERPRETACIÓN DE LAS CANCIONES DE VICTOR JARA.

Galeano, Eduardo. 1973 Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. Monthly Review Press.

Gatehouse, Mike. 6 Sept. 2021 “La Población: An Album for a Shanty Town.” Latin America Bureau, https://lab.org.uk/la-poblacion-an-album-for-a-shanty-town/.

Leiva, Jorge. “Quilapayún.” Quilapayún | MusicaPopular.Cl, http://www.musicapopular.cl/grupo/quilapayun/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

Miner, Horace (Horace Mitchell). 1957. American anthropologist. Body Ritual among the Nacirema. [Bobbs Merrill].

Moss, Chris. “Víctor Jara: A Beginner’s Guide.” Songlines, https://www.songlines.co.uk/features/a-beginner-s-guide/victor-jara-a-beginner-s-guide. Accessed 5 Dec. 2023.

Nitchun, Alyssa. 28 Nov. 2019 “Comment | Art Is Fuelling the Protest Movements in Latin America.” The Art Newspaper – International Art News and Events, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2019/11/28/art-is-fuelling-the-protest-movements-in-latin-america.

Simon, Scott, and Ned Wharton. 2 Nov. 2019 “‘El Derecho De Vivir En Paz’ Gives Voice To Protesters In Chile.” NPR. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2019/11/02/775533882/el-derecho-de-vivir-en-paz-gives-voice-to-protesters-in-chile.

Taffet, Jeffrey F. June 1997 “‘My Guitar Is Not for the Rich’: The New Chilean Song Movement and the Politics of Culture.” The Journal of American Culture, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 91–103.

Tyler, Andrew. 18 Sept. 2013 “The Life and Death of Victor Jara – a Classic Feature from the Vaults.” The Guardian. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/sep/18/victor-jara-pinochet-chile-rocks-backpages.

Warner Music Chile. 6 Feb. 2012 Victor Jara Discography: Manifiesto (2001). https://web.archive.org/web/20120206134238/http://www.nuevacancion.net/victor/warner87610.html.

Wilkinson, Tracy. 29 Aug. 2023 “Previously Classified Documents Released by U.S. Show Knowledge of 1973 Chile Coup.” Los Angeles Times, https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2023-08-29/us-releases-chile-coup-documents.

Wiser, Danny. 11 Nov. 2021 “CHILE: Manifiesto – Victor Jara.” 200worldalbums.Com, https://www.200worldalbums.com/post/chile-manifesto-victor-jara.

Zamorano, Patricio. 25 Sept. 2019 “Víctor Jara, a Sacrifice of Love.” COHA, https://coha.org/victor-jara-a-sacrifice-of-love/.