11 How Queer Social Movements Adapt to Change in Latin America

Esteban Macias

Introduction:

Latin America is a region of rich culture and diverse lands; everything from the food to the music changes to reflect the vast number of people who live in the region. Unfortunately, this diversity in people is not always seen as beneficial. Straying from the very clearly defined gender norms can be disastrous, as was proven through Mexico’s first nonbinary judge, Jesús Ociel Baena. They were found murdered in their home alongside their partner (Gonzalez). Though the broader picture of Latin America has some overarching commonalities, the individual character of each country is determined by a multitude of post-colonial factors. The political landscape changes from country to country for this exact reason. The extent to which countries are impacted by the themes of coloniality, the longstanding effects of colonialism on the minds and structures in place, impact much of the social and cultural climate, and nowhere is this more evident than queer social movements of Latin America. As a result of varying influence from themes like authoritarianism, public perception, and religion, queer social movements in Latin America find different levels of success and change the way they mobilize accordingly.

The legacy of authoritarianism is one of many themes that Latin American countries have in common. Many of the countries in the region have some form of experience with it (Cardoso), and such experiences deeply and permanently alter the way in which a country’s social and cultural norms are created and maintained. As such, countries that have a longer or deeper history with authoritarianism experience different outcomes socially and economically. Members of the LGBT+ community are especially vulnerable to the turbulence that comes from authoritarianism (Dion and Díez). Under authoritarian regimes, queer people are subject to violence from both the government as well as the general population and receive little to no support from the government.

The role of public opinion is critical in understanding both the success and the motivations of queer social movements in Latin America. Public opinion and education often become the crux of social movements across the region, as legislative change is irrelevant if not enforced (O Dossiê de Mortes e Violências). The secondary sources consulted for this paper show the general disconnect between legal systems and a country’s population through data that indicates a higher rate of death for members of the LGBT+ community, as even countries with strong anti-LGBT+ discrimination laws have higher rates of violence for queer people. Even in countries where progressive queer social policy exists, if the general public does not see the value in upholding it, the efficacy of the policy lowers substantially. Queer social movements in Latin America organize in order to solve this disconnect between policy and public opinion.

Religion and religiosity of a nation also directly impact the perception of queer people and the trajectory of queer policy, as nations with higher rates of religious influence often end up less accepting of the LGBT+ community. Catholicism in Latin America is a direct result of colonialism, and the impact it has on public opinion of the queer community changes legislative outcomes across the region. In countries where religion is more relevant to national identity such as Honduras, queer identities are typically seen as wrong (Pew Research Center). The inverse is also true – Argentina, a country in which Catholic ideas do not hold as much power, is home to a much more tolerant population, and much more pro-LGBT+ legislation. Religion’s effect on public policy forces queer social movements of Latin America to adapt to shift public perception.

Literature Review: Pre-Existing Factors That Create Discrimination

Authoritarianism and Public Opinion

While each country in Latin America has its own complex history surrounding political leadership and legislation, there is one common thread that ties the region together: the legacy of authoritarianism. Nearly every country in the region has had some form of authoritarianism in place following the destabilization of European colonialism (Pion-Berlin). In the past, these authoritarian regimes were based on the agrarian economies that were typical of the region, but a general shift towards modernization has changed how authoritarians maintain control in Latin America. Rather than one person rising and maintaining power alone, the military retains control by cycling new figureheads in and out of the executive role, shifting from caudillismo systems to bureaucratic-authoritarianism (Cardoso). This shift towards bureaucratic-authoritarianism is partly the reason that anti-LGBT+ rhetoric has remained so prominent in Latin America. Authoritarian dictators of Latin America have a long history of suppressing LGBT+ activists, particularly in countries like Argentina, Brazil, and Peru (Pion-Berlin). LGBT+ groups are forced to organize around the oppressive laws put in place by authoritarians.

Authoritarians use their influence as political and social leaders to maintain public opinion in a way that furthers their values and ideals, which contributes to the stigmatization of queer people in society. In the case of the LGBT+ community, this is done via criminalizing practices like same-sex marriage or gender expression. This stigmatization affects queer people in a variety of ways, but it becomes most salient when analyzing rates of violence against queer people and public acceptance in general. Generally, public perception of queer people, transgender people especially, is fairly negative (Barrientos and Bahamondes). This depiction is present in several aspects of pop culture, one such instance being Sosa Villada’s Bad Girls, a novel surrounding the life of trans women who survive vicious treatment and sex work. Villada depicts trans women or “travestis” as being accustomed to prejudice and violence. For example, the life expectancy of trans women in El Salvador is 41 years lower than the rest of the population (Amnesty International). The negative perception of the LGBT+ community changes how social movements mobilize, as it not only forces a need for legislative change, but social and cultural change as well.

Coloniality of Knowledge and Public Opinion

The coloniality of knowledge also impacts public perception through the implementation of hierarchies and discrimination that were not present in Latin America before colonization (Hernández-Medina). Prior to contact with the Spanish and Portuguese, Indigenous people of the region – the Nahua people in particular – had practices that involved what could be considered homosexual couples or expression of a third gender (Horswell). Only after the arrival of the Spanish and the criminalization of sodomy were these previously socially acceptable behaviors considered deviant or wrong (Sigal). Once sodomy was criminalized, an unspoken hierarchy was created. One that placed those who were perceived as socially deviant beneath the rest (Horswell). This hierarchy is still present in much of Latin America, and it contributes to the inequality that queer people face in the region.

As a result of poor public perception and the hierarchies that place queer people at a disadvantage, LGBT+ rights are usually used as a bargaining chip by political parties to garner support. While conservative groups are often wary of incorporating pro-LGBT+ messaging into their platforms, there are instances of both left and right-leaning political parties across Latin America including LGBT+ messaging as a way of increasing their voter base (Corrales). Political parties take advantage of LGBT+ voters because they know they have little to no choice; in a region in which discriminatory violence is commonplace, the slightest possibility of change is better than the alternative – a continuation of the death and discrimination that queer people face regularly. This concept serves as an example of Mills’ idea of the “sociological imagination” (Mills). Queer people across Latin America acknowledge their position as has been defined by history and consider the ways in which that position continues to create problems in the present. Seeking success and safety, they adapt to the various structures that are present in their society.

The issues of authoritarianism, poor public perception, and the coloniality of knowledge all coalesce to form a general context marked by inequality and discrimination for members of the LGBT+ community. Poor public perception makes it difficult for queer people to gain and maintain jobs (Bartels-Bland), and existing anti-discrimination legislation is rarely enforced. This places many queer people in a lower economic standing, which further aligns them with left-leaning political parties. As a result, LGBT+ social movements and leftist political parties align in order to achieve the shared goal of overthrowing authoritarian governments in the region (Dion and Díez).

The Case: The Effects of Authoritarianism, Public Perception, and the Coloniality of Knowledge on Queer Life in Latin America

Honduras

Different attitudes toward LGBT+ people in Latin America lead to different outcomes across the region, especially within the legal system, which changes how and why LGBT+ social movements organize and mobilize. Countries like Argentina and Brazil, which are much more accepting of queer people, have laws that are generally much more protective than that of Honduras or Peru (Barrientos and Bahamondes). In Honduras, one of the least accepting places of queer people in Latin America (Pew Research Center), queer people have begun to flee the country in search of asylum abroad. They are left with little choice, as their homes are bastions of bullying, discrimination, and violence, with little to no legal protections. In 2013, Honduras enacted a broad anti-discrimination law that included provisions for queer people. However, between 2013 to 2020, only four people were prosecuted based on anti-LGBT+ discrimination (Ghoshal). In 2018 alone, the number of LGBT+ identifying people in Honduras who were murdered climbed to over 40, 10 times the amount of people who were prosecuted for LGBT+ discrimination (Ghoshal). In other words, Honduras’ overall public perception of queer people makes it dangerous for the LGBT+ community, as legal protections are rarely enforced. In response, queer social movements in the country not only focus on shifting legislative outcomes, but also on defending queer people in the community who have been affected by the country’s discrimination. The Rainbow Association of Honduras is an organization that provides support for queer community members who have faced discrimination as a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity (United Nations). This defense provides the necessary support that the community is denied from the government as a result of the country’s religious values.

Argentina

Argentina – one of Latin America’s most tolerant countries of the LGBT+ community (Pew Research Center) – has more protections codified into law, however, queer people still face important challenges. Despite Argentina being one of the first nations in the world to legalize same-sex marriage, adoption, and the ability to change gender on government forms without a judge’s approval (NPR), queer people in Argentina still describe some level of discrimination (Corrales). The effect is not quite as severe, yet it persists nonetheless, leaking into areas of life such as employment and healthcare. In order to counter the stigma present in Argentine culture, lawmakers fight back by creating laws meant to increase equity and accessibility in the country. For instance, in 2021, lawmakers passed a bill that reserves 1% of all public sector jobs for transgender people (Valente). While there is still some discrimination present in Argentina’s culture, generally, the progressive nature of the country makes it a safer place for queer people in Latin America. As Argentina has much of the framework laid for its queer legislation, activists have shifted their focus to adapting laws to include more intersectional voices in service of increasing the efficacy of existing laws. When compared to Honduras, Argentina has had much more success with increasing the rights of queer people. This adaptation is only possible because of Argentina’s past success. If the country faced the same legislative issues as Honduras, queer activists would first have to advocate for basic protections before they could incorporate intersectional voices into their messaging (UN Women). Queer social movements in Argentina are only able to take this approach because of the framework that has established them as leaders in LGBT+ rights.

Brazil

Brazil serves as an interesting paradox, as it has LGBT+ protections that rival that of Argentina while remaining a distinctly threatening place for queer people to live. Brazil has been slow to adopt LGBT+ legislation, often leaving the issue to the courts to decide until social movements and international pressure force the creation of new legislation (Encarnacion). Legislation often provides support, and São Paulo is home to the largest Pride Parade in the world, but violent deaths are still much higher than the surrounding regions, with the peak reaching 445 violent deaths in 2018 (O Dossiê de Mortes e Violências). In order to counter the grave danger that members of the LGBT+ community face, lawmakers passed a bill in late August of 2023 that punished LGBT+ discrimination with prison time that matched that of discrimination based on race (Lavers). Brazil’s contradictory state places queer social movements in a unique position, as they have to split their focus to fight on multiple fronts. Unlike Honduras and Argentina where the focus of activist groups is placed on either creating protections or shifting public opinion, queer activists in Brazil have no choice but to combine both. Activists in Brazil operate under a dual mandate of ensuring that existing policy is enforced while also creating opportunities for the Brazilian public to interact with queer community members, such as the São Paolo Pride Parade. This parade serves as a way for the LGBT+ community in Brazil to express themselves while also highlighting some of the issues they face in Brazilian society. The slogan of the 2023 parade was “We Want Social Policies,” in order to emphasize that the issues that queer people in Brazil face are legitimate and to pressure politicians to acknowledge the struggles that queer people in Brazil face (Alves). The São Paolo Pride Parade serves as a way for Brazilian activists to fight discrimination on both a legislative and social front.

In sum, the three Latin American countries analyzed herein as a proxy to the region, create very different outcomes for members of the LGBT+ community depending on their social, political, and legislative climate. These three countries were chosen as they best represent the three schools of thought present in Latin America in regard to LGBT+ rights: Honduras as generally unreceptive, Brazil as supportive in legislation but not culture, and Argentina as relatively supportive in both aspects. All three of these Latin American countries share some experience with authoritarianism, Catholicism, and colonization, and each one responds to LGBT+ issues differently depending on the extent to which the previous three factors dominate public perception. In the case of Honduras, a late escape from authoritarianism paired with a strong Catholic influence has created a nation that is markedly hostile towards the LGBT+ community. While Argentina had a similarly late escape, the weaker influence of the Catholic church has allowed for an environment that is much more accepting of queer people, despite still having some difficulties. As such, queer social movements in Latin America have to strategically adjust the ways that they organize and mobilize, as the unique needs and influences of each nation change based on historical context.

Analysis: How Queer Social Movements Adapt Through Shifting Goals

Response From Social Movements

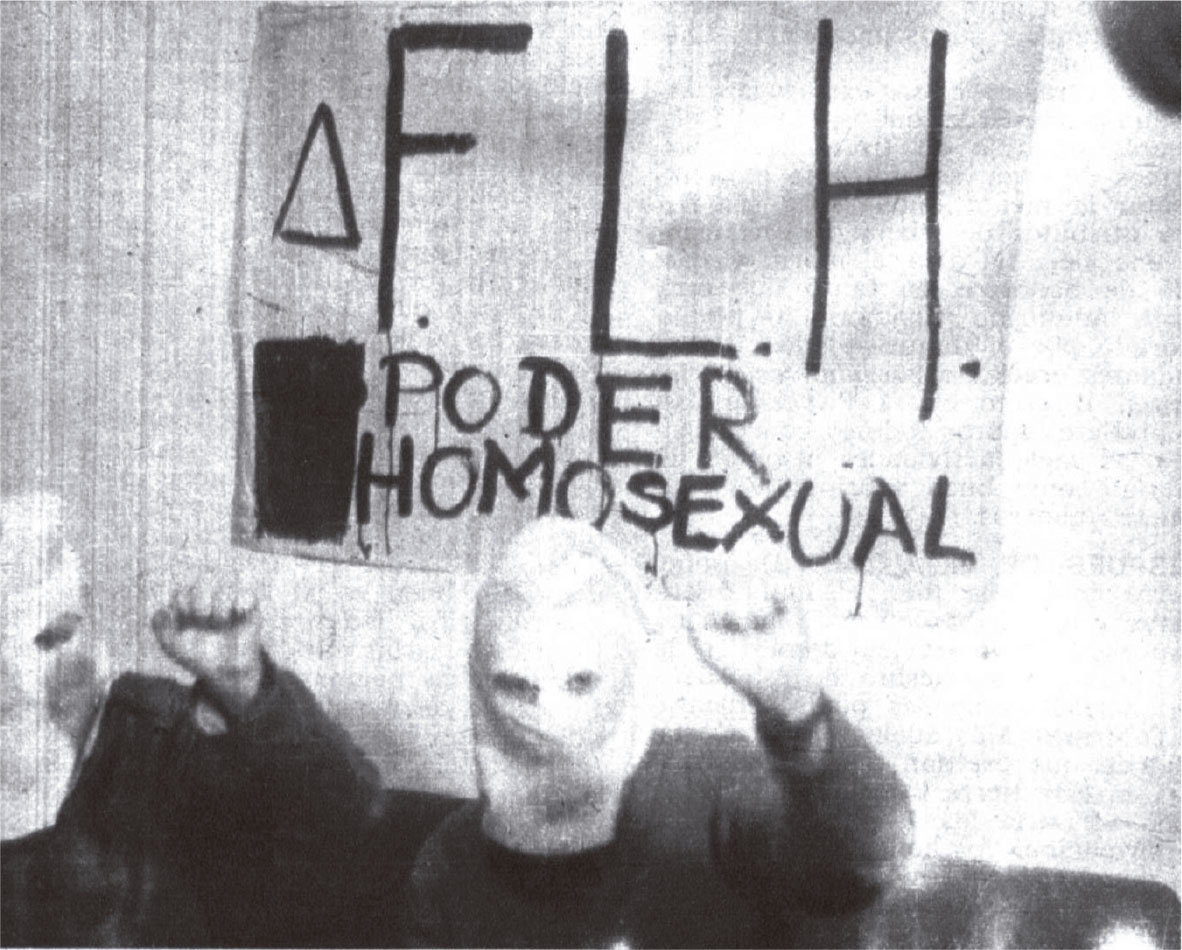

Authoritarianism often comes at the cost of violating human rights and limiting social movements, and queer social movements are no exception. The start or preservation of a dictatorship often leads to the destruction of queer social movements, and the end of one can signal the resurgence of the other, as is evidenced by Argentina’s Frente de Liberación Homosexual (FLH) and their brief disappearance. The FLH formed in 1971, and briefly dissolved in June of 1976 following the murder and torture of several members of the group during the military regime (Brown). The group was affected by the control of the authoritarian regime and had little choice but to go underground for the safety of their members. The end of the regime in 1983 marked an opportunity for resurgence, and the group returned in full force (Brown). The versatility of Argentina’s FLH is a characteristic that is common among many queer social movements of Latin America – it is also present in countries like Brazil, Chile, Honduras and others (Pion-Berlin). The shift in visibility changes the type of work that social movements engage in. While repressive authoritarians are in power, the focus of queer social movements shifts towards gaining equality, while during a democracy, the issue of public perception is also considered.

The focus on public perception on the part of queer social groups is necessary, as it fills in the gaps that legislation fails to provide or enforce. Even when legislation that creates protections for the LGBT+ community is passed, a positive public perception is vital to ensuring that it is actually enforced. This is partly why Argentina sees more success in queer equality than Brazil – on average, Argentina is much more accepting of queer people than Brazil (Barrientos and Bahamondes). In order to positively change public opinion, queer social movements often emphasize education on issues such as AIDS. When the epidemic first appeared in Brazil, panic swept the nation, mimicking the response of other countries like the United States. In response, the Associação Brasileira Interdisciplinar de AIDS began to dismiss misinformation and demand action from the Brazilian government (Green). Addressing AIDS in a way that dismissed public fear was vital at this point in time, as it reemphasized the humanity of the LGBT+ community. Activists focused on emphasizing the facts that surrounded the disease while fighting against the misinformation present in the nation as a result of the government’s silence. As pressure mounted from AIDS activists and their allies, the Brazilian government finally guaranteed the dispersal of free antiretroviral drugs (Green).

Challenging Religion

One major facet of changing public perception is achieved by challenging religion. The level of religiosity in a nation is a major determining factor of how accepting the population is of queer people, especially in Latin America. Though rates of Catholicism as a whole are falling across the globe (Pew Research Center), religious figures in Latin America are fighting back. Religious leaders of the Catholic church are joining populist movements in what Corrales deems “homophobic populism” in order to pursue anti-LGBT+ legislation, as both groups benefit in different ways (Corrales and Kiryk). Homophobic populism connects the financial and human capital of the Catholic church with the anti-establishment sentiment of populists to create a larger voter-base. In order to combat the growing anti-LGBT+ sentiment from religious institutions, queer social movements mobilize in a way that emphasizes decolonization (Dion and Díez). Conservative groups across Latin America deem queer issues as “gender ideology” issues as a way to dilute and link queer issues to feminist issues. Queer activists fight against this framing through mobilizing voters against political parties that seek to connect queer issues to those of traditional gender issues (Barreto). Resources are increasingly allocated to creating transnational content to combat the varying levels of homophobia and religiosity (Corrales). LGBT+ mobilization in Latin America has adapted to the needs of various countries based on religiosity.

The interplay of religiosity, public perception, and authoritarianism creates a unique landscape that impacts each country in Latin America differently. As the landscape changes, the goals and strategies of the various organizations adapt in order to match their circumstances. Cultural values and norms are created and set by authoritarianism and religion, which then go on to dictate public perceptions of queer people and the efficacy of policy.

Conclusion:

Through writing this essay, I learned about the myriad of responses that queer social movements of Latin America have depending on the individual factors that impact their nation. In the past, I had the tendency to view many social movements of Latin America through a homogenous lens, but that could not be further from the truth. Each nation has its own unique movements and organizations that adapt to the political landscape of their respective countries. I was particularly interested by the interplay of public opinion and individual outcomes for queer people. On paper, some parts of Latin America should be even safer than the United States as a result of their LGBT+ legislation, though this is not always the case. I had never really considered the impact that society has on how laws are actually implemented and followed, and how this necessitates cultural change from social groups in the region. I chose to use the three countries as a proxy for the entire region partly for the sake of simplicity, but also because together, they represent how countries in Latin America typically respond to queer social movements. Honduras, Brazil, and Argentina each provide insight into the ways in which factors like authoritarianism and public perception impact the success of queer social movements, as well as how those very same queer social movements react and adapt to the varying levels of success present within the countries they operate in. The constant adjustments and reorganization were fascinating to learn about, and I am glad that I had the opportunity to delve into so much detail.

The influence of authoritarianism on public opinion and legislative outcomes was something that I had not previously considered. I was shocked to learn the extent to which authoritarianism can impact a country, even years after the country had instilled democratic values and leaders. The reason these values persist is because while authoritarian figures may disappear, the citizens who lived under the regime do not, and if they maintain the cultural values created by the leader that they grew up with, the cycle of social repression continues. Queer social groups of Latin America are keenly aware of the role of authoritarianism in mobilization, and often adapt strategies to achieve success, such as taking advantage of the end of an authoritarian regime to begin community outreach. Queer social groups taking advantage of the change in regime serves as an example of how they adapt to changes in their environment; as the government and its values begin to shift and change, the strategies and successes that queer social movements find also begin to adapt and shift.

Religion plays a similar role in impacting the success of queer social movements, as religious institutions are still very influential in defining what types of behavior are considered “deviant” or wrong. It was interesting to learn the extent to which religion impacts legislation and public opinion. I had always guessed that it played some role, but I was not aware of just how large such an influence is. For some countries, religion is the major mechanism of anti-LGBT+ laws, and homophobic populism has surged. In order to combat the relationship between religion and homophobia, queer social groups are implementing strategies that emphasize the roles of queer people as natural. This is achieved through events that highlight positive aspects of queer life, such as Pride Parades.

Both religion and authoritarianism are influential largely for the role they have in influencing public perceptions of queer people. Public perception largely motivates legislative change, and the extent to which a country values that legislation determines whether or not it will actually be enforced. Since public perception is such a major mechanism of change for Latin America, queer social movements often focus on improving the general perception of queer people through educational programs that focus on eradicating negative stigmas.

In the past, I have done some research on various queer social movements in the United States, but this was the first time that I had ever done any research over those that exist in Latin America. I am very interested in social movements as a whole, and queer social movements – particularly those in Latin America – are so distinct in the ways that they form and mobilize, which made them incredibly interesting to learn about. I was interested in the subject because while I knew the goals and strategies of the two regions would be different, I didn’t know how they would change or what factors would encourage that shift. Through writing this essay, I learned about the various factors that determine individual outcomes for queer people across Latin America.

References

Alves, Thiago. 13 June 2023. “São Paulo’s LGBT+ Pride Parade Draws 3 Million People.” Brazil Reports, brazilreports.com/in-photos-sao-paulos-lgbt-pride-parade-draws-3-million-people/4966/.

Amnesty International. 11 Oct. 2021. “Covid-19 Is Making Life Even Harder for Trans Women in El Salvador.” Amnesty International, www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/08/trans-women-el-salvador-death-sentence-coronavirus/.

Barreto, Beatriz Santos. 12 Apr. 2023. “Mending the Divide: Lessons from LGBTQ+ Movements for Latin American Studies.” Wiley Online Library, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/blar.13485.

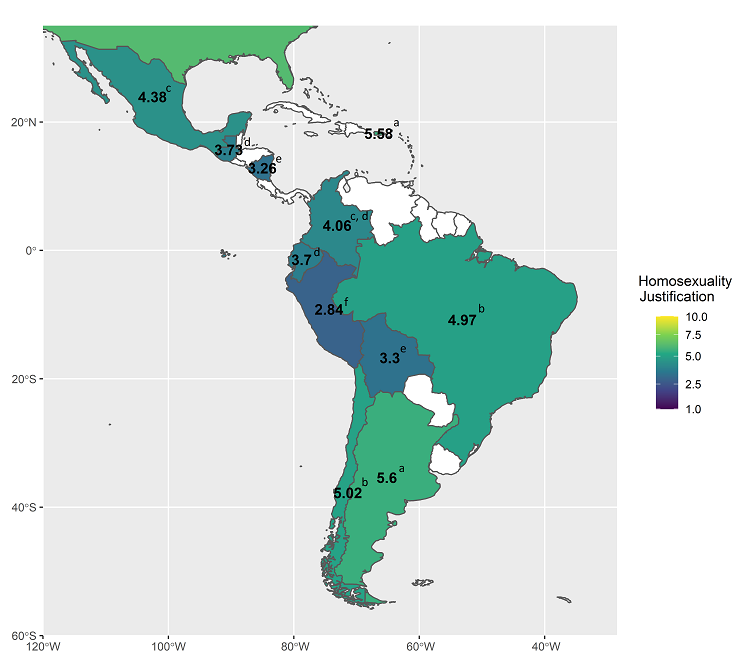

Barrientos, Jaime, and Joaquin Bahamondes. 30 June 2022. “Latin America over the Rainbow? Insights on Homosexuality Tolerance in the Region | LSE Latin America and Caribbean.” LSE Latin America and Caribbean Blog, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/latamcaribbean/2022/06/30/latin-america-over-the-rainbow/.

Bartels-Bland, Emily. 3 Nov. 2017. “How LGBTI Exclusion Is Hindering Development in Latin America and the Caribbean.” World Bank, World Bank Group, www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/06/13/como-la-exclusion-lgbti-obstaculiza-el-desarrollo-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe.

Brown, Stephen. Mar. 2002. “‘Con Discriminación y Represión No Hay Democracia’: The Lesbian Gay Movement in Argentina.” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 29, no. 2, 2002, pp. 119–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3185130.

Cardoso, Fernando Henrique and David Collier. 21 Jan. 1979. “The Characterization of Authoritarian Regimes.” The New Authoritarianism in Latin America, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1979, pp. 33–57.

Corrales, Javier. Dec. 2015. “The Politics of LGBT Rights in Latin America and the Caribbean: Research Agendas.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del Caribe, no. 100, 2015, pp. 53–62. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43673537.

Corrales, Javier, and Jacob Kiryk. 15 Aug. 2022. “Homophobic populism.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.2080.

Dion, Michelle L., and Jordi Díez. Winter 2017. “Democratic Values, Religiosity, and Support for Same-Sex Marriage in Latin America.” Latin American Politics and Society, vol. 59, no. 4, 2017, pp. 75–98. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44684367.

Encarnacion, Omar G. Feb. 2018. “A Latin American Puzzle: Gay Rights Landscapes in Argentina and Brazil.” Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 194-218. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/hurq40&i=199.

Ghoshal, Neela. 28 Mar. 2023, “‘Every Day I Live In Fear.’” Human Rights Watch, www.hrw.org/report/2020/10/07/every-day-i-live-fear/violence-and-discrimination-against-lgbt-people-el-salvador#3006.

Gonzalez, Gabe. 17 Nov. 2023, “Remembering Jesús Ociel Baena.” GLAAD, glaad.org/remembering-jesus-ociel-baena-fearless-lgbtq-advocate-and-latin-americas-first-nonbinary-magistrate/.

Green, James N. 28 Sept. 2020. “LGBTQ History and Movements in Brazil.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. Oxford University Press. https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-840

Hernández-Medina, Esther. 7 Sept. 2023. “The Coloniality of Knowledge.” Latin America Through Sociology and Literature, Pomona College. Class lecture.

Horswell, Michael J. 2006. Decolonizing the Sodomite: Queer Tropes of Sexuality in Colonial Andean Culture. University of Texas Press.

Lavers, Michael K. 25 Aug. 2023. Brazilian Supreme Court Rules Homophobia Punishable by Prison. https://www.washingtonblade.com/2023/08/25/brazilian-supreme-court-rules-homophobia-punishable-by-prison/, https://www.washingtonblade.com/2023/08/25/brazilian-supreme-court-rules-homophobia-punishable-by-prison/.

Mills, C.W. Sept. 1959. “The Sociological Imagination.” Oxford University Press, New York.

NPR. 8 Aug. 2021. “Argentina Goes Further to Protect LGBTQ Rights with New Law on Trans Employment.” www.npr.org/2021/08/08/1025845759/argentina-goes-further-to-protect-lgbtq-rights-with-new-law-on-trans-employment.

Ociel Baena, Jesús. 21 Jun 2023. https://x.com/ocielbaena/status/1671703195733704705?s=20

Observatório de Mortes e Violências LGBTI+ No Brasil. 2022. O Dossiê de Mortes e Violências. “Observatório de Mortes e Violências LGBTI+ No Brasil.” May 2023, observatoriomorteseviolenciaslgbtibrasil.org/dossie/mortes-lgbt-2022/#dossi%C3%AA-completo-de-mortes-e-viol%C3%AAncias-contra-lgbti+-no-Brasil-em-2022.

Panorama. 24 Aug. 1972. “Vida cotidiana. Homosexualidad: las voces clandestinas”.

Pew Research Center. 13 Nov. 2014. “Chapter 5: Social Attitudes.” Religion in Latin America, Washington D.C. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2014/11/13/chapter-5-social-attitudes/

Pew Research Center 13 Sept. 2022. “Modeling the Future of Religion in America.” Washington D.C. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/09/13/modeling-the-future-of-religion-in-america/

Pion-Berlin, David. 2 Jan. 2018. “Authoritarian legacies and their impact on Latin America.” Latin American Politics & Society, vol. 47, no. 2, 2005, pp. 159–170, https://doi.org/10.1353/lap.2005.0024.

Sigal, Pete. “Latin America and the Challenge of Globalizing the History of Sexuality.” The American Historical Review, vol. 114, no. 5, 2009, pp. 1340–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23303430.

United Nations. 17 Sept. 2021. “Fighting for LGBTQI+ Rights in Honduras.” OHCHR, www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2021/09/fighting-lgbtqi-rights-honduras.

UN Women. 18 Nov. 2022. “Pushing Forward: Dismantling Anti-LGBTIQ+ Discrimination in Argentina.” United Nations, www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2022/11/pushing-forward-dismantling-anti-lgbtiq-discrimination-in-argentina.

Valente, Marcela. 25 June 2021. “Transgender Job Quota Law Seen ‘changing Lives’ in Argentina.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, www.reuters.com/article/us-argentina-lgbt-lawmaking-trfn/transgender-job-quota-law-seen-changing-lives-in-argentina-idUSKCN2E11QV/.

VTVCanal8. 2015. “Dictadura militar en Argentina.” https://social.shorthand.com/VTVcanal8/32onaqxvUf/dictadura-militar-en-argentina.