5 Frida Kahlo: Her Passion, Her Past, and Her Vision

Introduction

It is shocking to think that one of the most famous artists of our time almost never created a work of art, opting for the medical field instead. Frida Kahlo nearly became a doctor had it not been for the tragic cataclysm that reconstructed her reality and kickstarted her new perspective on life. Kahlo’s art reinforces the notion that tragedy is a breeding ground for beauty but it is imperative to recognize that it was not exclusively this tragedy that made her art so mesmerizing. A combination of her tragic past, her electrifying passion, and her unique perspective is that which Kahlo’s inspiration is comprised.

Frida Kahlo is an artist who captured the hearts and minds of the art community and the rest of the world through her work. Her work was lauded and loved because of its surrealist components and enthralling, oftentimes heart-breaking depictions. But it was the inspiration behind these pieces—her passion, her past, and her perception—that continue to enamor people to this day.

Kahlo lived a life full of passion and extravagance. She had a tumultuous and electrifying romantic life through her marriage but also through her affairs and open bisexuality. Her past brings an era of tragedy and difficult experiences that clearly haunted Kahlo for the rest of her life and had lasting effects in how she lived and how she created art. And the artist’s perception of the world around her comes through very clearly in her art and how she interacted with the world. She had fiery opinions on politics, norms, and art. All three of these components appear and manifest themselves in the art works that Kahlo created and operate as her main modes of inspiration.

Theoretical Framework

The main aspect that connects Kahlo’s inspiration with the works we’ve examined in classis that art is a key part of Latin American culture; every nation in the region has notable artists and works that formed the national culture and identity. In class we were able to examine how art is utilized by different countries as a form of resistance. In the article Indigenous Feminist Rap Music as a Form of Resistance Jasmine Ali emphasizes that, “The gender system that dominates the majority of Latin America is based on white superiority and patriarchy”. Kahlo herself broke numerous gender conventions and roles. Because of this rebellious stance, there are many themes and sources of inspiration in her pieces in which the art community was not used to. Kahlo’s inspiration was deeply a reflection of her identity and sense of self. As an openly bisexual woman, her refusal to be a housewife, and defiance of Euro-centric, conventional beauty standards she was not in the business of reinforcing the gendered society she lived in (Moura).

Along similar lines, we were able to see art as a form of self-expression through the work of Josefina Baez and her performance Dominicanish. Baez represented the way she was feeling in her own world and in the surrounding community through the dance and recitations she did. Kahlo’s work is not unlike this. As a bedridden social oddity, Kahlo had limited agency to express the way she felt and her paintings worked as a medium of communication. As someone who had high hopes of enterting the medical field prior to her accident, Kahlo didn’t know what to do in her recovery time; “Although she initially hoped to combine her love of medicine and sketching to become a medical illustrator, the lingering pain from her injuries forced her to abandon the idea and drop out of school. She turned to painting to fill the hours” (Maranzani). In her recovery period but also later in life when she returned to being bedridden, painting was a passion but also a solace and an agency.

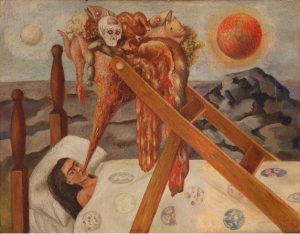

Her recovery period presented many horrors that she expressed through her paintings. In this piece “Without Hope” she is conveying the way she felt when her doctor prescribed her a diet that revolted her.

Her recovery period presented many horrors that she expressed through her paintings. In this piece “Without Hope” she is conveying the way she felt when her doctor prescribed her a diet that revolted her.

Her work also connects to the coloniality of knowledge that we were able to explore in class. This concept refers to the fact that those who colonize (Europe) get power and stay in power because of their ability to control knowledge, and it lends itself to analyzing the effect that these leftover institutions put in place by the colonizers had on the women of Mexico, but more specifically Kahlo herself. Kahlo’s art combated gender stereotypes and roles, and conventional beauty standards. Because of this, she had strong feelings about being categorized as part of the Surrealist Movement. The Surrealist Movement was something that originated in Europe and nearly completely stayed there. There were limited exchanges in the self-proclaimed hub of surrealism of surrealist works outside of their circle. When Andre Breton, the self-proclaimed founder of surrealism, visited Diego Rivera and discovered the art of Frida Kahlo for the first time–which had very obvious surrealist components—Breton immediately tried to acquire this “knowledge” (per se) and place it under the European Surrealist Movement.

Kahlo was not pleased with Breton’s compartmentalization of her art. Critics have said that his words “both flatter and patronize” and that “once again, the woman artist arrives intuitively at an ideological position created by man in her absence. Her work is devalued because it supports a priori theoretical positions without either shaping or expanding them” (Chadwick 111). Also in relation to Kahlo’s revolutionary tendancies, the piece Afro-Cuban Cyberfeminism discusses the way in which Latin American and Caribbean women are retaking cultural center-stage by overthrowing institutional expectations: “First, because it refuses a sole commitment, polyamory disrupts the notion of the revolution as the ultimate promise. Second, the advocacy for fluidity in this blog puts black women’s necessities at the center of social discussions, which operates contrary to what should be the perfect revolutionary’s (white male’s) ideal, the eternal sacrifice for the love of the revolution” (Sierra-Rivera). Both of these concepts, specifically, are parallels to the messages Kahlo was sending through her art. Her revolutionary passion was a fundamental aspect of her art. Kahlo worked against colonizers’ institutional categorization and expectations.

Case & Analysis

Her Passion

Kahlo is a monumental artist whose fundamental inspiration came from her passion, her past, and her perception. To investigate her passion, one has to examine all aspects of her social life. Kahlo had a lively romantic life up until and throughout her marriage to Diego Rivera, another notable artist. Kahlo had multiple affairs before and during her marriage with Diego Rivera and apparently, “fidelity was out of the question” (PBS). She wrote extensively in her personal diary about her passionate relationship for Rivera; “I’d like to paint you, but there are no colors, because there are so many, in my confusion, the tangible form of my great love” (Kahlo 205). She continued to write about her complex and layered relationship with love and how it can be both a source of pain and inspiration.

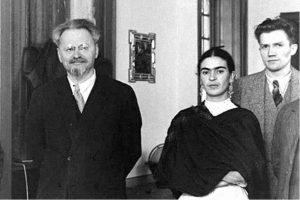

Her personal relationship with those around her were also pivotal and incredibly influential in shaping her art and her inspiration; “Noting Kahlo’s interest in art and philosophy, involvement in an anarchist literature group, friendships with prominent Mexican figures in philosophy, as well as close relations with political circles, Başkaya argued that these must also have helped shape her artistic character and style” (Agency). Within her “friend group” she also had passionate affairs with great thinkers. Most notably, she had a 3-year long relationship (during her marriage) with Leon Trotsky. This manifested itself in her diary but also in her art; “she’d even dedicated a striking self-portrait to him” (Gotthardt). A group of revolutionary, leftist, and artistic intellectuals were Kahlo’s acquaintances with whom she bounced ideas off. It was a liberal, radical echo chamber that fuelled Kahlo to be more passionate about issues and themes.

Her love of Mexico was undeniable in her actions but also in her art. Kahlo went to lengths to make sure she embodied her country as much as she could; “At some point she even changed her birth date from 1907 to 1910, the start of the Mexican Revolution, and elided the ‘e’ in ‘Frieda’ to make her name more authentically Mexican” (Burke). As a half German and half Mexican woman, she displayed a love for Mexican culture and attempted to show it through her art, being a crucial part of her identity. This passion was exemplified in her art; “She tended to use Aztec symbols, flowers, monkeys, and skulls in many of her paintings” (Frida Kahlo’s Revolutionary Nationalism). Josephina Baez expresses her love of her origins and the compilation of her homes within her identity; “I am from where I was born. / I am from where I am right now. / I am from all the places that I have been. / I am from all the places that I will be” (Baez 2). In an interview Baez reiterates her love for her country; “I am placed here [places fist over her heart], this is where my nation is” (Baez/Deckman 7). Much like Baez’s sentiments, Kahlo’s geographical home was inextricably intertwined with her identity, and by extension her inspiration to create art.

Her Past

Kahlo led a very confined and sickly life. At age 6 she became permanently effected by polio but returned to normalcy for a little over a decade before another tragedy occurred. When she was 18 years old, a horrific accident befell her. A traffic accident “shattered both her spine and her plans” (Watt). Kahlo herself wrote, “In all my life I have had 22 surgical interventions” (Kahlo, 251). Although these physical ailments permanently affected her to the degree of being bedridden for multiple years, she was able to draw artistic inspirations from her hardships.

Frida Kahlo never had children, which is why she is rarely seen as a maternal figure, yet she experienced hardships in this arena, as well. When her first pregnancy was aborted for personal reasons, her subsequent two pregnancies resulted in miscarriages which took a large mental toll on Kahlo (Samguino). Kahlo would manifest this aspect of her hardships in the themes of her work; “She chose to paint raw and real experiences of women’s life. Frida takes the viewer inside a woman’s mind and let them examine the fears, suffering, and passions that were secretly hidden inside” (Moura). All these tragedies in Kahlo’s life framed her as a victim to circumstances and, in a different world, someone who would’ve succumbed to their hardships. However, Kahlo did not respond this way. She would paint it out; “in the act of painting and in the resulting canvases, she documented her own attempts to survive pain, to make sense of it, to act out through images layered with fantasy, irony, and allegory” (Udall). She was observed to carry her past with grace, but not as someone who was scared to express these intense difficulties; “’Using Mexico’s bright colors, she depicts the darkness within her,’ Başkaya went on. ‘Especially the dull look in her auto-portraits and the broken smile on her face are like the silent scream of the pain revealing itself among the multicolored, sparkly hues’” (Agency). Her work is reflective of the hardships she endured in her past.

Her Vision

The influence that Kahlo had on the art community is undeniable, but the influence that the art community tried to impose on Kahlo was at times contentious—bringing Kahlo’s’ unique point of view and vision into the spotlight. Frida Kahlo’s perception is one of the most defining aspects of her inspiration, but in addition to that, reveals her thought process. Although surreality appears to be the inspiration of Kahlo’s work, she vehemently denied being a surrealist; “Kahlo called herself a realist who painted her own life” (Chadwick 112). Surreality was her reality. She expresses her feelings about surrealism in her diary; “”we take refuge in, we take flight into irrationality, magic, abnormality, in fear of the extraordinary beauty of the truth” (Kahlo 248). Kahlo also revealed through her diary that painting is something she did exclusively for herself, not for the sake of the “movement”, not any exhibition, nor fame.

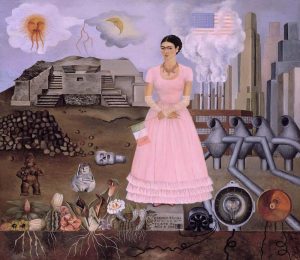

The political motives and ideals that Kahlo had were exemplified in her art. As was already explored, Kahlo had a love for Mexico, but with that love came an intense type of nationalism for the culture of the country; “This emphasis on the Aztec, rather than Mayan, Toltec, or other indigenous cultures, corresponds to her political demand for a unified, nationalistic, and independent Mexico…She was drawn, rather, to Stalin’s nationalism, which she probably interpreted as a unifying force within his own country. Her anti-materialism had a distinctly anti-U.S. focus” (Jacolbe). Her strong opinions were a driving force in the type of work she created. It is interesting to note her passionate work in the political sphere because modern, neoliberal anecdotes typically only paint Kahlo as an unconventional artist, rather than the woman who had a deep and potent perspectives. Relating back to Sierra Rivera’s piece on cyberfeminism, radical leftist ideals are something that women of Latin America and the Caribbean are harnessing to further their long-suppressed role in society. Kahlo channelled her political spirit into her art, to put into words the injustices that were occurring and voicing her strong opinions.

Conclusion

Kahlo’s passion, past, and vision are all facets of the artist that needs to be dissected in order to understand the inspiration for her art. Her passion is something that was based on her relationships with those around her. Her husband and all other romantic affairs she had were sources of love and she wrote extensively about it in her diary. Her friends were revolutionary people who had inflammatory ideas. Kahlo’s love for her country was both passionate and radical since she held a vision for its future. Much like Josephina Baez expressing her innate and intense love for her home but also much like Sierra Rivera’s call to action against the suppression of women’s role in Latin American and Caribbean culture, Kahlo relayed her particular ideas and opinions through her art. All of these people around her served as a source of influence. Her art reflected her political agenda, her romantic passion, and her personal relationships. Kahlo’s past was a very difficult part of her life that clearly had severe effects on the way she led the rest of her life. As a victim to numerous diseases and injuries, in addition to miscarriages, Kahlo led a confined, bedridden lifestyle. This prompted her to view the world is a very particular way and prompted her to draw a certain dark, cynical, but powerfully honest aspect to her art.

Sources

- Ali, J. (2023, May 19). “Warmikuna Quñusqa Kasun” or “women, we are united”; indigenous feminist rap music as a form of resistance -Jasmine Ali. Voices of Change Navigating Resistance and Identity in Latin America. https://pressbooks.claremont.edu/las180genderanddevelopmentinlatinamerica/chapter/jasmine-ali/

- Moura, N. (2018, December 17). Frida and feminism. Women’n Art. https://womennart.com/2017/03/08/frida-and-feminism/

- Maranzani, B. (2020, June 17). How a horrific bus accident changed Frida Kahlo’s life – biography. Biography. https://www.biography.com/artists/frida-kahlo-bus-accident

- Chadwick, W. (1985). Women artist and the Surrealist Movement. Thames and Hudson.

- Sierra-Rivera, J. (2022). Afro-Cuban cyberfeminism: Love/sexual revolution in sandra álvarez ramírez’s blogging. Latin American Research Review, 53(2), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.323

- Public Broadcasting Service. (n.d.). The Life and Times of frida kahlo . life of frida . people in frida’s world. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/weta/fridakahlo/life/people.html#:~:text=Rivera%20and%20Kahlo%20had%20been,remarried%20late%20the%20following%20year

- Kahlo, F., Fuentes, C., & Lowe, S. M. (2005). The diary of frida kahlo: An intimate self-portrait. Abrams.

- Agency, A. (2021, July 13). Frida Kahlo: Remembering Mexican painter Honoring resistance, life . Daily Sabah. https://www.dailysabah.com/arts/portrait/frida-kahlo-remembering-mexican-painter-honoring-resistance-life

- Gotthardt, A. (2019, April 30). How Frida Kahlo’s love affair with a Communist revolutionary … – artsy. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-frida-kahlos-love-affair-communist-revolutionary-impacted-art

- Burke, C. (2020, March 3). Frida Kahlo in “Gringolandia.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/03/books/review/frida-in-america-celia-stahr.html?searchResultPosition=5

- frida kahlo’s revolutionary nationalism. COW Latin America. (2021, March 12). https://cowlatinamerica.voices.wooster.edu/archive-item/frida-kahlos-revolutionary-nationalism-2/#:~:text=Ultimately%2C%20Frida%20Kahlo%20played%20a,was%20an%20essential%20revolutionary%20nationalist.

- Baez, J. (2008). Comrade, Bliss Ain’t Playing.

- Baez J., Deckman J. (2018) El Ni’e: inhabiting love, bliss, and joy A conversation with Josephina Baez https://sakai.claremont.edu/access/content/group/CX_mtg_166421/Readings%20Class%2021%20-%20November%207th%2C%202023%20-%20Borderlands%20and%20the%20Latin%20American%20Diaspora%20_Literature_%20%2B%20Guest%20Lecture%20with%20Dominicanyork%20Poet%20and%20Performer%20Josefina%20B%C3%A1ez/Deckman%20-%20El%20ni%E2%80%99e%20-%20Interview%20with%20Josefina%20Baez.pdf

- Watt, G. (2005, August 1). Frida Kahlo. The British Journal of General Practice. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1463226/

- Sanguino, J. (2023, July 15). Frida Kahlo: Her accident, inspiration and legacy in the Art World. EL PAÍS English. https://english.elpais.com/culture/2023-07-15/frida-kahlo-her-accident-inspiration-and-legacy-in-the-art-world.html

- Udall, S. Frida Kahlo’s Mexican Body: History, Identity, and Artistic Aspiration Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Autumn, 2003 – Winter, 2004), pp. 10-14 (6 pages) https://doi.org/10.2307/1358781•https://www.jstor.org/stable/1358781

- Jacolbe, J. (2019, March 3). Frida Kahlo’s forgotten politics – jstor daily. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/frida-kahlos-forgotten-politics/