12 Impact of Maras and the Government Among Salvadorans Living in Poverty

daoo2023

- Flag of El Salvador

Introduction

“Kill, rape, control” is the motto for Mara Salvatrucha, also known as MS-13. Maras, a Central American term for gang, in El Salvador have a mean entry age of only 15 years old. Most gangs were formed by young teenagers living in poverty. Maras such as Barrio 18 and MS-13 are gangs that originated in Los Angeles but as they were deported to countries with a weak rule of law, such as El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, they increased in power. Violence was and continues to be present by these rival gangs from North America to Central America. In El Salvador, more specifically, maras expand as an alternative to the poverty many in the country are in because of the lack of education, employment, and opportunities. Because they live in poverty, many Salvadorans experience violence in their neighborhoods because of the control and power maras have and use to abuse them.

The government has the purpose of protecting and providing for a country’s betterment. In El Salvador, the government fulfills this role in some cases such as the response it had to the March attack of this year by President Bukele’s current administration. Although the government occasionally provides support and protection from violence by the maras, this is not always the case. In particular, the government’s lack of action to provide more opportunities for those living in poverty is one of the main reasons for the growth of youth gangs. Not only does this cause many young Salvadorans to live in violence, but the growth of maras increases violence among poor neighborhoods controlled by them. In other cases, the government is also often the reason for discrimination against poor Salvadorans due to the abuse or misuse of political power many administrations have demonstrated throughout the country’s history. Due to such governments, the safety and protection of Salvadorans living in poverty is often uncertain.

In this seminar about Latin America through Sociology and Literature, we discussed several of these topics. Through sources that provide data regarding the issues of inequality and power in the region including El Salvador such as unemployment. Through readings that provide examples of governmental abuse of power toward Latin Americans living in poverty, due to the goal of economic and political growth of each country. Through sources that emphasize the reason for and danger of authoritarianism, a reason for worry among poor Latin Americans who are not protected by the government but rather used and taken advantage of. These sources as well as others will be used to describe the danger of abuse of power and control as they relate to the violence present in El Salvador, both in the past and present by maras and the government.

Theoretical Framework:

Governmental Abuse of Power through Exploitation and Violence

The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa is a novel that exemplifies governmental abuse of power. It focuses on Rafael L. Trujillo who was the dictator of the Dominican Republic from 1930-1961. For instance, in the novel he justifies his orders to kill many Haitians in the Dominican Republic by saying that it was done “for the good of the country” by preventing “the blacks from colonizing us again” (Llosa 164). His concern was that had he not done that, “the Dominican Republic would not exist today” (Llosa 164). Trujillo’s goal during his time in power was to ensure that Dominicans had power over Haitians and to prevent the opposite from occurring. This is why he gave orders to soldiers to kill many Haitians living in the Dominican Republic in the 1937 massacre. Trujillo explains that those in power, specifically soldiers, never trembled because “I gave the order to kill only when it was absolutely necessary for the good of the country” (Llosa 168). The abuse of power by Trujillo allowed those still in power below him, such as soldiers, to abuse their power as well. As a result, thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent were killed.

As well as the government’s abuse of power using violence, Open Veins of Latin America by Eduardo Galeano demonstrates the exploitation of people in the region for resources. It describes Latin America “continues to exist at the service of others’ needs” since their resources are “for rich countries which profit more from consuming them than Latin America does from producing them” (Galeano 11). This is an example of a group in power, developed countries, abusing their power by exploiting underdeveloped countries. Due to the power imbalance among these countries, a greater gap is created between them regarding their wealth, resource availability, and overall power. As Latin American countries are taken advantage of for their resources and labor, developed countries continue to bring benefits for their own country.

Background on Maras

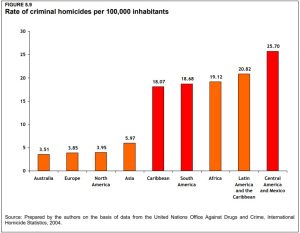

Not only does the government abuse their power, but powerful groups such as gangs or maras in Latin America abuse their power as well. The UNDP report “Our Democracy in Latin America” (2011) analyzes how poverty, homicides, and maras are linked in El Salvador in 2000 and 2008. Due to the high numbers of murders of Latin America, with El Salvador having an increase of 39.4% from 2000 to 2008, the report argues that the cause is that “governments have often proven unable to ensure citizens’ fundamental right – the right to life” (67). With Central America and Mexico having the highest homicide rates of 25.7 per 100,000 inhabitants between these years, the report mentions that such a high rate is caused primarily by maras. The report emphasizes two main goals of these mara groups which are to “defy each other to death over territorial rivalries” and to murder many victims in poor neighborhoods that “do not pay taxes or fees for the extortion that they impose on public urban transport and on businesses” (Dalton, 166). The desire for control, specifically of territory and people, is one of the main driving forces of maras in regions such as El Salvador. Since maras have high number of members and weapons, they continue to increase this control which results in more poor Salvadorans suffering from it. Not only do maras affect people outside of their groups, primarily poor civilians, but the rise of poverty has caused many young Salvadorans to join these maras. As poverty and lack of opportunities increases for the youth, the number of mara members and homicide rates increase.

Not only does the government abuse their power, but powerful groups such as gangs or maras in Latin America abuse their power as well. The UNDP report “Our Democracy in Latin America” (2011) analyzes how poverty, homicides, and maras are linked in El Salvador in 2000 and 2008. Due to the high numbers of murders of Latin America, with El Salvador having an increase of 39.4% from 2000 to 2008, the report argues that the cause is that “governments have often proven unable to ensure citizens’ fundamental right – the right to life” (67). With Central America and Mexico having the highest homicide rates of 25.7 per 100,000 inhabitants between these years, the report mentions that such a high rate is caused primarily by maras. The report emphasizes two main goals of these mara groups which are to “defy each other to death over territorial rivalries” and to murder many victims in poor neighborhoods that “do not pay taxes or fees for the extortion that they impose on public urban transport and on businesses” (Dalton, 166). The desire for control, specifically of territory and people, is one of the main driving forces of maras in regions such as El Salvador. Since maras have high number of members and weapons, they continue to increase this control which results in more poor Salvadorans suffering from it. Not only do maras affect people outside of their groups, primarily poor civilians, but the rise of poverty has caused many young Salvadorans to join these maras. As poverty and lack of opportunities increases for the youth, the number of mara members and homicide rates increase.

Authoritarianism

Giving more power to the government creates authoritarianism, which is viewed both positively and negatively. Fernando Henrique Cardoso emphasizes that authoritarianism results from the fact that “obedience without consent is a weak foundation for a stable and durable political order” (Cardoso, 34). Indeed, the military plays a crucial role in obtaining “obedience” from the population in El Salvador since they are in a position of power. He mentions that in a military authoritarianism, “it is the military institution as such which assumes the power in order to restructure society” (Cardoso, 35). In this type of authoritarian government, the military uses its power, which consists primarily of violence through weapons, to maintain order in a country. The danger of an authoritarian ruling is that the obedience “without consent” signifies an abuse of power by the military to fulfill their goals despite civilian’s disapproval. Authoritarianism is very problematic as it creates an unequal distribution of power, which raises concern for many people. Although there are many dangers and concerns of authoritarianism such as the abuse of power previously mentioned, many others accept this type of ruling. With the desire for protection in an underdeveloped country, supporters of authoritarianism believe they will receive such support and protection by accepting those in power. They believe giving more power to those in power is an effective way to protect themselves in a country full of poverty, violence, and other major disadvantages.

The Case:

Salvadoran Civil War

Throughout the history of governments in El Salvador, there have been many situations in which they have abused their power. An example of this trend was the reorganization of the state during the presidency of Rafael Zaldívar (1876-1885). The government brought economic growth from exploiting coffee as the main economic sector in the country (monoculture) based on “the expropriation of indigenous lands and the creation of a repressive security apparatus composed of a permanent army, police and paramilitary forces” (Chavez, 1). The exploitation of people, specifically the working class, and resources for such economic growth demonstrated the state’s abuse of power. Due to years of governmental abuse of power over the people and authoritarian rule for many years, the civil war took place from 1980-1992. This 12-year conflict caused “at least 70,000 deaths, 500,000 refugees, tens of thousands of wounded and maimed, thousands of “disappeared” and a deep-seated psychosocial trauma that will plague Salvadorans for several generations” (Chavez, 1). The civil war negatively affected thousands during and after the war by initiating a time of increased violence.

Progression of Mara Violence

After hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans immigrated to the US during the civil war, a US deportation policy caused as many as 20,000 Central Americans to be deported between 1996 and 2005. Many of these were gang members in California that spread to Latin American regions, increasing in size in their smaller home countries such as El Salvador. Government plans such as the “Firm Hand” and “Super Firm Hand” plan attempted to arrest many of these Mareros, or mara members. As the number of detainees increased, the number of murders caused by Mareros increased “from 2,172 in 2003 to 2,762 in 2004 and 3,825 in 2005” (Gomez, 4). To reduce murder rates and disputes between the maras, the government created negotiations with gangs which was called the “truce.” By maintaining homicide rates low, MS-13 and Barrio 18 developed political and economic strategy that “marked the beginning of a profound metamorphosis from street gangs to criminal organizations, with political and territorial control” (Gomez, 4). The truce was later broken as the homicide rates “doubled from 2015 onwards, reaching 6,657 murders in that year” and “making this small country –the so-called thumb of the Americas– the most violent in the world” (Gomez, 5).

After hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans immigrated to the US during the civil war, a US deportation policy caused as many as 20,000 Central Americans to be deported between 1996 and 2005. Many of these were gang members in California that spread to Latin American regions, increasing in size in their smaller home countries such as El Salvador. Government plans such as the “Firm Hand” and “Super Firm Hand” plan attempted to arrest many of these Mareros, or mara members. As the number of detainees increased, the number of murders caused by Mareros increased “from 2,172 in 2003 to 2,762 in 2004 and 3,825 in 2005” (Gomez, 4). To reduce murder rates and disputes between the maras, the government created negotiations with gangs which was called the “truce.” By maintaining homicide rates low, MS-13 and Barrio 18 developed political and economic strategy that “marked the beginning of a profound metamorphosis from street gangs to criminal organizations, with political and territorial control” (Gomez, 4). The truce was later broken as the homicide rates “doubled from 2015 onwards, reaching 6,657 murders in that year” and “making this small country –the so-called thumb of the Americas– the most violent in the world” (Gomez, 5).

The increase of Mareros in the maras was not only caused by the civil war but also the poverty young Salvadorans live in. The OECD mentions that in the years between 2010 and 2014, “between 20,000 and 35,000 of gang members are 20 years old on average, with a mean entry age being 15 years.” Such high numbers of young Salvadorans joined these maras not only because of the violence that sparked from the civil war, but also the negative changes that it brought to the country. The OECD lists these factors as “high rates of poverty, inequality, under- and unemployment and school dropouts, dysfunctional family structures, easy access to arms, alcohol and illegal drugs, chaotic urbanization, and finally local gang structures and organized crime.” These circumstances and living situations cause many young Salvadorans to join maras and live a violent life. The growth of youth violence not only directly impacts those who join these gangs but the poor neighborhoods that fall victims of their violent behavior and actions.

March Attack Response/Public Opinion

A significant, recent event that demonstrates the impact of gang violence on poor Salvadorans was the March attack. Diana Roy’s article “Why Has Gang Violence Spiked in El Salvador?” describes that on March 25 and 27, “at least eighty-seven people were murdered in a wave of violence that Salvadoran authorities blamed on Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18.” The main dispute between these rival mara groups was territorial control and because of disagreement amongst them, many innocent civilians living on these territories were killed. These people murdered by the gang members were poor Salvadorans not involved with the maras in any way but targeted regardless of their innocence since they were in the streets when the shootings took place. As response to the March attack, the current president Bukele “authorized the national police to conduct warrantless raids and mass arrests” (Roy, 1) of more than seventeen thousand suspected gang members. His response was considered a “mano-dura” or “iron-fist” response since it consisted of the immediate imprisonment of many gang members in these neighborhoods. When major disputes occur such as the March attack, the common action by past presidents would be to establish a truce among these gangs but Bukele’s “iron-fist” response was contrary to this action. In the article “Ending El Salvador’s Cycle of Gang Violence,” Cruz and Speck argue that: “Despite (or perhaps because of) his iron-fisted policies, the Salvadoran president remains popular, with approval ratings that have hovered between 80 and 90 percent.” Such high ratings for President Bukele emphasize the approval for his response, primarily because it brought immediate change and security in these neighborhoods. Safety increased since the arrest of the Mareros decreased homicide rates by 60 percent.

Even though President Bukele received high approval ratings, his response to the March attack also brought concern of a rise of authoritarianism. In their article “Explosion of Gang Violence Grips El Salvador, Setting Record,” Abi-Habib and Avelar emphasize that “the state of emergency on Sunday has stoked concerns that Mr. Bukele will use the weekend violence to empower himself even further.” Their concern of a rise of authoritarianism results from the immense support Bukele received from his actions since this would signify him gaining more power and control in the country. Although having power allows him to make impactful changes for major concerns such as violence in the country, too much power could result in abuse of power, which has been present the history of El Salvador during past authoritarian governments.

Analysis:

Governmental Abuse of Power

Violence in El Salvador was initially mostly the result of abuses of power by the authorities. In Open Veins of Latin America, Eduardo Galeano described how developed countries grew economically by exploiting of the labor and resources of Latin American countries. This example of abuse of authority was likewise present in El Salvador’s history between the government and poor Salvadorans. The reorganization of the state during President Zaldívar administration was such an event. This involved the use of land and poor Salvadorans for monoculture that would only bring economic growth and more power to the government. Both examples demonstrate the use of labor and resources for economic growth. This creates power inequality as those in power grow in power but those exploited lose power and control in their lives. Also previously mentioned, The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa demonstrated an example of someone’s abuse of political power for themselves and their ideology. This was Trujillo, who ordered the killing of many Haitians to give Dominican Republicans more power in the country. Similarly, El Salvador was under the military authoritarianism Cardoso mentioned, which caused many deaths and disputes during the civil war. The government’s control over people for many years created a build-up of resentment and rebellion. Both countries demonstrated the government’s violent solution to maintain power and control despite people’s disagreements. As a result, civilians also turned to violence to fight for themselves and against those abusing their governmental power. This is what caused Trujillo’s assassination and the years of violence among Salvadorans in the civil war. The civil war not only affected those fighting during those years, but it “implanted fundamental features of the culture of violence: the use of terror and terrorism as a method for dealing with social conflict, the lack of value and respect for human life, and the proliferation and use of firearms” (Chavez). This culture of violence is what began the growth of youth violence and gang violence.

Violence from Poverty

Like the UNDP and the OECD reports mentioned, El Salvador has high numbers of homicide rates and murders caused by maras. The control maras have, level of violence in the country, and number of youths in maras are similarly expressed by the UNDP during 2000-2008 and by the OECD during 2010-2014. The build-up of power maras have increased in the country which in hand increased violence, specifically in poor neighborhoods. These maras also grow in members as more young Salvadorans join due to their various, terrible living conditions. “As long as societies fail to incorporate these youth and give them a choice, and until this work is meaningfully funded, no significant changes will occur” (Our Democracy in Latin America, 173). Based on this concept, providing opportunities and better living conditions would reduce youth violence, but since violence has only increased in the past years, primarily by the control and power of maras, this has not significantly changed.

Rise of Authoritarianism in El Salvador

The most recent event that demonstrates the power maras have and the increase in violence caused by them was the March attack. Due to their rise in power since the civil war, Bukele’s “iron-fist” response to this tragic event was made to reduce homicide rates. Because they had political power, Bukele and Trujillo were both able to make immediate decisions that would change their country. They were/are men in political positions that when given their level of control, they can act upon their intentions and views for the way society functions. Bukele’s desire for gang control was achieved because since thousands of Mareros were arrested, homicide rates decreased. This brought a positive response as it caused many people to grow their support for Bukele’s presidency. However, the increase in support Bukele received because of his response also brought concern of an increase of authoritarian rule. Since Bukele also ordered military and police officers to arrest all of those associated with gang activity, he portrays the military authoritarianism Cardoso mentioned. By using military figures for physical control of these neighborhoods, the government has control of what belongs to the people. A worry rises in Salvadorans who fear that the increased support for Bukele is blinding the rise of authoritarianism in his presidency as his supporters desire the protection his “iron-fist” response brought after the March attack. Although his response indeed decreased gang violence, the increased control by the government and the military in these areas can result in authoritarian rule.

Conclusion

Overall, violence in El Salvador is caused by maras and the government. This took place both in the past and present time. Events such as the state’s reorganization in the 1880s and the civil war from 1980 to 1992 showed the result of violence by abusing governmental power. Those in power such as the presidents and governments have political control that influences and drives the way the country is ran. All their actions in these events demonstrated the desire for personal wealth through the exploitation of resources and labor. This benefited them economically, but their actions led to an increased resistance and violence by the poor Salvadorans being used. The consumption and exploitation for economic growth, in El Salvador and various other countries, results in violence between those with power and those without power.

Such chaos of a violent history led to the formation and maintenance of maras in El Salvador. As a result, this led to an even greater increase in violence as gangs in this country fought for more control of territories for their economic and power growth. Not only did this create dispute between the government and maras who desire to have the most power in the country, but poor neighborhoods become victims of their violent actions. Such event was demonstrated by the death of many civilians during the March attack. Despite the years of the government abusing their power, Bukele’s response to the March attack was viewed as an opposite reaction by most Salvadorans. His “iron-fist” response to imprison thousands of Mareros was positively viewed since he used his power for the protection and security of these neighborhoods under control by the maras.

Due to the history of violence in El Salvador, Bukele’s response was also viewed negatively as it brought concern of authoritarianism. This was a main cause for the civil war and the increase in violence and mara members, bringing fear of history being repeated. The power Bukele gains brings concern because although he reduced gang violence, either maras or the government having too much control in the country results in poor Salvadorans suffering. In El Salvador and any other country, too much power by one group in a country creates chaos and violence. Whether this is a gang or the government itself, a distinct group with too much power leads to too much control over the country. To maintain such a level of power and benefits that come from it, violence and disorder fall specifically into poor neighborhoods. Therefore, the history of imbalance of power in El Salvador has caused maras and the government to have a major impact of Salvadorans living in poverty.

References

Abi-habib, Maria, and Bryan Avelar. “Explosion of Gang Violence Grips El Salvador, Setting Record.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 28 Mar. 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/03/27/world/americas/el-salvador-gang-violence.html.

“Chapter 5: Three Top-Priority Public Policies: A New Fiscal Approach, Social Integration, And Public Security.” Our Democracy in Latin America. 2011.

Chávez, Joaquín M. “An Anatomy of Violence in El Salvador.” NACLA, 25 Sept. 2007, nacla.org/article/anatomy-violence-el-salvador.

Collier, David, and Fernando Henrique Cardoso. “On The Characterization of Authoritarian Regimes in Latin America.” The New Authoritarianism in Latin America, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1979.

Cruz, Jose Miguel, and Mary Speck. “Ending El Salvador’s Cycle of Gang Violence.” United States Institute of Peace, 20 Oct. 2022, www.usip.org/publications/2022/10/ending-el-salvadors-cycle-gang-violence.

Galeano, Eduardo, et al. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. Three Essays Collective, 2010.

Llosa, Vargas Mario, and Edith Grossman. The Feast of the Goat. CNIB, 2013.

OECD, Key Issues Affecting Youth in El Salvador. www.oecd.org/countries/elsalvador/youth-issues-in-el-salvador.htm. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.

PASTOR GÓMEZ, María Luisa. The political influence of the maras in El Salvador. IEEE Analysis Paper 32/2020. http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2020/DIEEEA32_2020LUIPAS_maras Salvador-ENG.pdf

Ramsey, Geoffrey. “Tracing the Roots of El Salvador’s Mara Salvatrucha.” InSight Crime, 24 Apr. 2023, insightcrime.org/news/analysis/history-mara-salvatrucha-el-salvador/.

Roy, Diana. “Why Has Gang Violence Spiked in El Salvador?” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 4 May 2022, www.cfr.org/in-brief/why-has-gang-violence-spiked-el-salvador-bukele.