1 Narconovelas across the border: U.S and Latin America

ddcx2023

Experience and Popularity

Growing up in Sinaloa I was guaranteed to know someone who knew someone that knew someone whose relative or friend had an encounter with organized crime. We were never that far detached from violence. My aunt saw someone get kidnapped, my mom’s work neighbor’s brother was killed by drug cartels, and my family has seen guns in use a few feet away. It is a tragedy of a state so deeply tied to the history of drugs and home to the infamous Sinaloa Cartel. In 2019, with the arrest of the son of “El Chapo” Guzman, it escalated to a shootout where gunfire could be heard across the corners of the city. Calling home brought stories of how things were scary and my mom could only answer with “Stay safe” only for the same occurrence to happen again in early 2023 with the rearrest of El Chapo’s son, Ovidio Guzman Lopez. Even more recently, the battle between the Mexican government and the cartel continues with the arrest of “El Nini”, security chief for the Guzman family, tied to the gunfire spread on an apartment complex housing military families in 2019. The gunfire was an attempt to pressure the army to release the son of El Chapo. In 2019 it was effective as the soldiers were ordered to release Ovidio Guzman Lopez.

It is never a situation that one wants to experience. It creates fear that one might be caught in the crossfire for being in a normal place at the wrong time. Watching from the outside in is a different experience. There is still fear of losing loved ones but there is a sense of detachment. It is a sense of condolence rather than grief. It was a change that I observed in my family as my mom who was previously indifferent to narconovelas developed a taste for them. She expressed that it was different seeing a realistic make-believe story than hearing a real story.

Telenovelas, Latin American soap operas, has been a popular form of entertainment for a long time but as of 2008, with the release of Sin tetas no hay Paraiso, the genre of narconovelas emerged into mainstream, rising in popularity with consecutive releases of new content. The series La Reina del Sur ranked No. 1 in the 10 o’clock time slot, across all U.S. broadcast networks on the night of its release (Sanchez). Success over both Spanish and English renditions of series marked a clear foundation for the future of narconovelas.

Narconovelas have captured the attention of the public despite or rather because of their heavy themes and violent depictions. Narconovelas have fundamentally changed the industry, creating various subsections of interest across the continents. It is particularly noticeable that the growing industry has in some sense seeped into media across the border. Taking La Reina del Sur as consideration, the success of a female lead as a drug lord became so popular it was made into an English remake, but that would not have happened without the demand made after the first narconovela Sin tetas no hay paraiso and the demand across the border with American big hit Breaking Bad. In a similar line Netflix may not have touched Narcos without first acquiring Pablo Escobar: El Patron del Mal just to circle back with Narcos: Mexico. It is a feeder loop that makes the genre expand. Although the concept of mafia and organized crime have been well known in the broadcasting network as evidenced by the Godfather and others, Narconovelas along American drug series formed a new expectation of consumption of the media.

Themes across works of Latin America

Bad Girls by Sosa Villada is a book describing the life of travesti prostitutes with a found family dynamic in Cordoba, Argentina. It is significantly touching and mindful of the struggles of the otherwise abandoned girls. The focus it places on gender identity and sexual orientation-based discrimination brings to mind the intersectionality of struggles as finding a place of acceptance leads them to a discarded part of society and prompts a struggle through poverty. The path of prostitution allows for encounters with violence and drugs. It is to the level where prostitution is their source of income. It puts into perspective the places trans-women and more broadly women in poverty are forced to partake in for survival. They are a vulnerable group, victims of drug use, but that is not what the focus is. It focuses on the shared joys and natural worries through hardship. In doing so, Villada creates empathy for the girls that are an afterthought for society but are still members of it regardless of where society wants to place them. It strikes as a story of a strange juxtaposition where loss, resilience, happiness, and fragility of life are present within the lives of these “bad girls”.

The book Papi by Rita Indiana is a tragic and amusing journey through the perspective of a growing child. Her constant love and admiration for her father, or Papi, makes her blind to the reality of the situations he places her in as a drug dealer moving through the roads evading capture. Her childish perspective distorts the story in a manner that forgives all gruesome characteristics as if it were a game. The portrayal of the struggle of the dad to keep his daughter happy brings a sense of sympathy for an attempt to maintain the connection pure of the outside violence that chases him. The themes of drug trafficking seen through the girl’s eyes serve as a form of commentary on the effects of persecution for families associated with drug trafficking. It is culturally significant to present a side of narco life that gets hidden by the glamor associated with it through novelas and corridos. The unnamed girl presents a close yet outsider’s perspective on the narco life of her father and later on shows the fallout at the end of it. Its basis in the Dominican Republic and development in Florida presents a connection across border lines showcasing how organized crime is not isolated to Latin America.

The Stranger by Georg Simmel places the idea of a stranger as a necessity to differentiate a relationship’s value and freedom. Simmel claims that the individuality of strangeness is a binding agent of many people. The stranger can be an identity of an inner outsider as physically distant but part of a community or physically close but socially disconnected. In putting forth the contradicting concept of being a stranger, Simmel calls out the role of the stranger as a challenger of tradition, a facilitator with freedom of mobility, and a confidant with an unbiased perspective. This suggestion of challenger may give way to a reexamining of structures accepted as a part of the culture or generalities, but it offers a dual possibility for an unbiased perspective. A stranger may be inserting notions from their new environment or may be presenting bias that relates to a different identity, but in the context of the group they are a stranger in, they are tackling an observed incongruity. Simmel tells of the benefits and status of a stranger but does not reflect on the common interpretation of strangeness as a feeling of isolation. Following the line of isolation, how groups emerge from trying to abridge those worlds they are half placed in. It reflects the complexities of belonging to a group while navigating the tension between commonality and uniqueness as an outsider.

Americanity as a Concept by Anibal Quijano and Immanuel Wallerstein claims that the sentiments associated with the Americas are an attachment of the idea of modernity built through a sense of newness, coloniality, ethnicity, and racism. Ethnicity is a consequence of coloniality followed by the creation of racism to uphold the social hierarchy, which often hides behind the ideas of ethnic hierarchies. Quijano and Wallestein comment on how economic and political institutions were essentially built ex nihilo except in the Andean and Mexican regions effectively bypassing the various Indigenous cultures that heavily influenced several aspects of colonial governance. While it is true that the concepts mentioned of hierarchies are built off European justification, it does away with an aspect of the complex relation that developed differently in the United States and Latin America while still maintaining that differences arose from British and Spanish approaches in religion, Indigenous affairs, and development. The result of the United States presenting itself as European society in America was an ideology of supremacy in “manifest destiny” that pushed for expansion outside its borders into Latin America. The United States placed itself as a controlling figure stepping into Panama, Mexico, and other countries. Latin American countries were left as dependents, subordinates of the Eurocentric powers with a crisis of power brought by a failed attempt at national-democratic revolution.

Prevalence in Narconovelas

Gender is a key component in Narcoculture with depictions of women and men often split into categories granting the power to the man and a sense of sensuality to the woman. Although the different versions of the series have a fairly accurate adaptation to the novel, the version made for audiences in the United States “ invents other sensationalist episodes about women models” in their role as “mules and prostitutes for local and foreign drug traffickers.” serving as “construction of poor young women by the shady forces of the drug traffickers.” (Cabanas). Cataline, the protagonist, comes to a realization that “ if she embodies the neoliberal ideals of greed, capitalist consumption, and commodity fetishism, she will achieve the status and societal respect she desires.” Within the telenovelas there tends to be a show of machismo which is further in liaison with guns as a study shows, “Antagonism and all of the hypermasculinity indices were closely associated with GunEnscores. Higher GunEn scores were associated as well with higher frequencies of lifetime aggression including alcohol-related, criminal, and potentially lethal acts”( Mason et al. 375-376)

An exceptional phenomenon that adapts to audiences, narconovelas are reflective of cultural differences and experiences. Tailored explicitly for a diverse U.S. Latino audience, this rendition provides a unique perspective on the narrative to engage its viewers. (Cabanas) This adaptability may have first given rise to its success to Sin tetas no hay paraiso as the “novel went into its thirteenth edition and sold over 100,000 copies in its third year–and this was before it became one of the most popular telenovelas of all time, in its Colombian (Caracol), US (Telemundo), and Spanish (Telecinco) versions.” A good portion of narconovelas are produced by Telemundo for U.S. audiences while Caracol television produces for Colombia. Netflix became a distributor of these series and a producer as well, targeting an English-speaking audience.

Themes of Narconovelas may surround various aspects of political, personal, and societal critics. Gustavo Bolivar’s novel aims to spotlight the issue of Colombian youth’s dismissiveness of education in pursuit of quick wealth and underscores the urgency of addressing the problem (Morello). A small sample study of 358 responses, of which 182 had watched Narcos, measured the reasons why audiences watched the series Narcos in the United States and Colombian regions. From the data, there is a split that shows the most likely reasons someone from the United States to watch Narcos were for relaxation, to escape from life, and curiosity and interest in violence (Cano 16). Comparatively, the top reasons for Colombians to watch the series were that they identify with the survivors or because it makes them feel less lonely (Cano 17).

Narcocorridos are a musical expression that hangs on the traditional corridos with a dip into narco culture. Although narcocorridos are the only form of musical expression that speaks of violence and drugs, it is a widely recognized genre with popular artist like Los Tigres del Norte and Peso Pluma having songs in the genre. Each artist has their own interpretation of the genre. For Los Tigres del Norte, the narcocorridos are fictitious pieces while their regular corridos reflect reality telling the events as they happened, however, the composer of their famous song “La Reina del Sur”, claims the opposite in which narcocorrido is the one that tells true stories (Ramirez-Pimienta). It is hard to find a conclusive agreement over narcocorridos, especially since they have long existed taking over the stories of heroes to retell of the growing cultural phenomenon of national acknowledgement of narcoculture. It is a deep history in which “ los corridos de narcotrafico han existido desde las primeras decadas del mismo. Sus antecedentes se remontan a los corridos de contrabando de fines del siglo XIX y pdncipios del XX” (Ramirez-Pimienta). In relation to narconovelas narcocorridos and musical scores pair well to present the short story synopsis brought by the opening theme.

Analysing across the borders

The two catalyst series Breaking Bad and Sin tetas no hay paraiso contributed to the popularization of drug depictions in T.V. Breaking Bad series won appraisal from audience and critics alike after winning the Emmy for best drama series and reaching 10.3 million viewers, with a 5.2 rating among adults 18-49 (Hibberd). It is a U.S based drug themed series mirroring the popularity of the Latin American renditions of drug series in Sin tetas no hay paraiso, whose original Colombian release in 2006 predated that of Breaking Bad, and the U.S release followed a few months after Breaking Bad’s premiere in 2008. There is an overlap in themes and driving points within the stories but they each give their interpretation and representation of it. In the Sin tetas no hay paraiso, the two factors directing the story are poverty and a woman’s body. It is a relationship between the desire to escape poverty and the willingness to enter prostitution to do so. Like Bad Girl’s, prostitution is a means to an end. The deterioration of a woman’s body is considered a necessary sacrifice. Similarly, the motivations of Walter White in Breaking Bad emerge in his inability to pay medical bills and sustain his family. They adapt to the audience they speak to as Breaking Bad has an American-focused family struggle while Sin tetas no hay Paraiso speaks on the struggle of young girls in Latin America dealing with sexual exploitation. Laced with religious allusions of “La Diabla, paradise, and even the surname Santana (alluding to Santa Ana, the mother of the Virgin Mary)—encode a moral commentary on the main characters for their “immoral choices” better serve to find ground with Hispanic religious audiences (Cabañas). The theme song of the U.S version of Sin Senos no hay paraiso carries lyrics that singla motivation and a nuanced conversation between a man and a woman. The irony of “la belleze natura…tu dulce ternura, no necesitas nadamas” being spoken by the man that supposedly holds the money while in the story it is constantly mentioned how the men only desire a carved figure even if it is fake. From the first sentence the woman speaks, “Yo solo quiere poner me las bien buenas para asi salir de este lugar. Yo so lo quiero que usted me de un poco de dinero…” it directly goes against all previous statements by the man of love and natural beauty. Breaking Bad’s theme is purely instrumental but resembles a tune of a old west cowboy music which aligns with the images of New Mexico or rather the states near the Mexican border forming a stereotype of lawless venture in the land.

Following the initial success of drug-centered dramas, both U.S. and Latin American networks continued to produce narco series. Two series following Pablo Escobar, a deceased Colombian drug lord, take stage one being produced by studios in the United States taking more creative liberties, Narcos, and the other, Pablo Escobar: El Patron del Mal. Narcos takes creative liberties more loosely serving as entertainment than a retelling of Escobar’s story and damage. Although both play into the idea of hypermasculinity with their portrayal of powerful male druglords, one leans towards telling a narrative to survivors of how their perpetrators came to take action while the other leans towards the curiosity of violence centered around police versus cartel conflict. Pablo Escobar is no stranger to Colombia, but his story is not one of glory; it is made understood in El Patron del Mal that his actions are condemned but still a part of Colombian history through the opening theme. Its opening line being, “Quien no conoce su historia esta condenado a repetirla” is an immediate reminder that the narconovela is not one to foster glorification rather it serves as a reminder of what fatality the drug lord brought to the world. From the lines chosen to be in the introductory song, “convertiste mis hermanos en sicarios” and “que no se borre de tu mente, en honor a nuestros cuerpos que cayeron vil mente” are outright call outs to the transformation brought to the neighborhoods that the drug world drew from but maintains a firm stance even through it. In the full song

“Aunque mi rostro es de barrio de techo de lata

Mi alma y mi esencia no la compras con plata

Una nación completamente maniatada

Entre narcotráfico y corrupción mi bandera secuestrada

Una patria como la mía tropieza o resbala

Pero se pone de pie y se limpia la cara”

Overall the song is lined with a strong sense of love for Colombia that acknowledges its many faults and struggles but reduces to collapse from it. The mention of poverty but moral upstanding regardless of the hold of drug trafficking is intertwined with the story of Pablo Escobar’s effect on the nation. It gives an insight from a part to the community to a stranger or even another insider. Towards the end of the series, El Patron de Mal showcases a call back to Papi’s vulnerable figure that deteriorates the images of glorious power within the drug world. The intro song of Narcos takes on a more romantic ballad style with no explicit mention of the nature of the show. The repetition of “Tuyo sera” may be indicative of greed within the narco world, but does not give more than a mildly stereotypical interpretation of what may be pictured in a documentary of narcos.

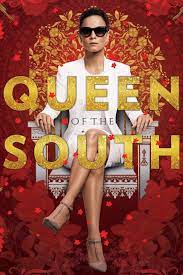

Finally, a series that stems from another, La Reina del Sur, and its English remake The Queen of the South speak on the popularity and demand for the series across country lines for English and Hispanic audiences. La Reina del Sur has an opening corrido following a similar format to those made of real narcos telling their life. Queen of the South follows its U.S. sisters and has no lyrics, with an eerie instrumental score. While promotional material may have art that is reminiscent of Mexico’s cultural art, it does not capture the culture like La Reina del Sur does with its more overt relation. Both series fall back on gender ideas but they partially subverse the frail women narrative with their powerful female drug lord protagonists.

The series that have an American perception are often dismissive of the true problems outside of the U.S. borders. It is an American centrism that allows for these oversights and one that is only reflected in Latin American creations as the U.S. tends to be the ultimate goal of expansion within the drug world. A mirror of U.S. expansion into Latin America for control is tossed back in under a new power of deadly dealings. The idea of stranger emerges for audiences, especially U.S. Hispanic audiences that may be looking back at conflicts in their countries that can be most readily seen through the consumption of entertainment media.

Relevance in Summary

Narconovelas are a nuanced interpretation of real-life events as they can overplay themes of unbalanced gender roles, violence, and crude overpasses but can simultaneously highlight accurate struggles within gender discrimination, risk, and cultural significance. American series may carry a divergent cover of drug dealing, but they overlap in some aspects as they are each focused on relating to their target audiences. The genre’s adaptability and its resonance with the masses make it a powerful form of storytelling, connecting communities and serving as a cultural and, in some cases, therapeutic outlet.

From an outsiders’s perspective, narconovelas can be tools of introduction to continual conflicts if done with a sense of respect for it. It is a careful intersection that needs balance to succeed in accommodating a national grievance over the endured violence but may explore a sense of escapism to keep pushing for discussion of the narco world.

In essence, narconovelas represent an intersection between cultural phenomena and tragic histories. As the genre continues to grow, there is a need for acknowledgment of its nuanced portrayal, which includes elements of fear, reflection, and the potential for social critique. As audiences navigate the criticism and praise directed at narco media, it becomes evident that the genre is here to stay, intertwining with various facets of identity and cultural expression.

References

AP News. “Mexico’s Arrest of Cartel Security Boss Who Attacked Army Families’ Complex Was Likely Personal.” 24 Nov. 2023, apnews.com/article/mexico-nini-sinaloa-cartel-arrest-287aad09f5bb256656deaf49e060d578. Accessed 28 Nov. 2023.

Business Wire. “‘La Reina Del Sur’ Draws Best Audience Ever for Telemundo Entertainment Program, Averaging Nearly 4.2 Million Total Viewers.” x31 May 2011, www.businesswire.com/news/home/20110531007102/en/%E2%80%9CLa-Reina-Del-Sur%E2%80%9D-Draws-Best-Audience-Ever-for-Telemundo-Entertainment-Program-Averaging-Nearly-4.2-Million-Total-Viewers. Accessed 28 Nov. 2023.

Cabañas, M. (2012). Narcotelenovelas, Gender, and Globalization in Sin tetas no hay paraíso. Latin American Perspectives, 39(3), 74-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X11434303

Matson, et al. “Gun Enthusiasm, Hypermasculinity, Manhood Honor, and Lifetime Aggression.” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, vol. 28, no. 3, 2019, pp. 369–383., https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1420722.

Morello, Henry James. “Voiceless Victims in Sin tetas no hay paraiso.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, vol. 19, no. 4, Dec. 2017. Gale Literature Resource Center, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A529046142/LitRC?u=claremont_main&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=88ab41b7.

Cano, Maria Alejandra. “The War on Drugs: An Audience Study of the Netflix Original Series Narcos” Undergraduate Student Research Awards. 24, 2015.

https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/infolit_usra/24

Ramírez-Pimienta Juan Carlos. “Del Corrido De Narcotráfico Al Narcocorrido: Orígenes Y Desarrollo Del Canto a Los Traficantes.” Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, vol. 23, 2004.

Hibberd, James. “’Breaking Bad’ series finale ratings smash all records.” Entertainment Weekly, 30 Sept. 2013, https://ew.com/article/2013/09/30/breaking-bad-series-finale-ratings/.

Cotter, Padraig. “How La Reina Del Sur Compares to Remake Queen of the South.” ScreenRant, 26 Sept. 2019, screenrant.com/la-reina-del-sur-queen-south-remake-comparsion/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2023