14 Huacas, Extirpation, and Syncretism: Andean State-Building Through Political-Religious Domination in the Inca and Spanish Empires

Simón Solano

Introduction

When I was 11, my mother uncovered a nativity scene made of ceramic she had received from a friend while in Peru. The nativity scene was made up of small figures with cute, oversized heads and faces, including a llama, a cow, the Virgin Mary, Joseph, and a tiny baby Jesus. The figures all wore chullos, Andean ear flapped hats made traditionally with vicuña, alpaca, or llama wool, and were wrapped in ponchos made from colorful, warm textiles native to the region. This tiny nativity set, which fit in two cupped palms, is the result of the long process of religious syncretism found in the Andean region as a result of colonialism beginning with the Inca Empire’s conquest.

While the separation of church and state as a concept has a long history with disparate origins, the two civilizations examined in this paper, the Inca (and the broader Andes), and the Spanish Empire, during the pre-colonial and colonial periods, both faced political-religious domination. The head of state of the Inca Empire was known as the Sapa Inca, or sole ruler, and was revered as a god, also known as Intip Churin, or the “Son of the Sun.”[1] His power was not cemented by popular support, but by the state religion in which he found himself as a centerpiece. Similarly, in Iberia, the Spanish monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand found their political power justified by the divine right of the ruler, as well as through the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula, a process in which they forced the Moors who inhabited Iberia out of their territory.[2] From ~1200 CE-1538, and 1609-1740, the Andes saw politics and religion as ideologically integral to each other, and saw religion utilized as a form of state-building. In the case of the Inca Empire, state-building materialized through huacas and the Cusco Ceque System, whereas in the Andean Spanish Empire, the Extirpation of Idolatry sought to further these processes.[3] By outlining the systems of imposing political power through religious means present in the Andes, in contrast with the Spanish colonizers, this paper will seek to better understand their similarities and differences, as well as how local peoples confronted their conquest. In the pre-colonial period, I will examine huacas and the Cusco Ceque System, and in the colonial period, I will examine the formation of Andean Catholicism as a syncretic religion, with the ends of understanding how the two strengthened their respective empires and formed shared religious beliefs which grew their empires.

Theoretical Framework – Histories of Exploitation and Theories of Misrepresenting Observers

In Jasmine Ali’s article, “Warmikuna quñusqa kasun” or “Women, we are united”; Indigenous Feminist Rap Music as a Form of Resistance, Ali explores the music of Peruvian Indigenous feminist rapper Renata Flores and how her music, which blends Spanish and Quechua, acts as a form of resistance against coloniality and its disenfranchisement of women throughout Peru. One of Flores’ albums, titled Isqun, tells the story of 5 different indigenous women who the common Spanish narrative erased.[4] These women’s stories are told through Quechua and Spanish, Flores’ way of acknowledging both parties that existed in the Andean world during the colonial period, while highlighting the importance of Indigenous Andean women.[5] In her paper, Ali explains one of the reasons why Andean peoples’ histories are so predominantly Spanish, “since the Andean people speak Quechua, a language that has no written form, the Spanish chronicles provide the only written documentation of Andean society from that time.”[6] This omnipresence of Spanish testimony in the archives and record is partially a result of Quechua’s lack of a written form, but it also is a result of colonialism’s form of operation: erasure and dehumanization of the colonized.[7]

This lack of indigenous records regarding an indigenous system can lead to misunderstandings and misrepresentations, as seen in Horace Miner’s article, Body Ritual Among the Nacirema. Miner’s article presents the perspective of an anthropologist upon the Nacirema people, who are in fact the American people (Nacirema is American spelled backwards). Throughout the article, Miner uses irony to show the various aspects he saw in the Nacirema’s lives, examining the medical system in excess, which all presents the Nacirema as a backwards, foreign people through the use of defamiliarization.[8] Miner’s article is an excellent example of what can happen to ethnographic accounts that lack understanding and awareness, presenting an ethnography that defamiliarizes and dehumanizes the group, leading to extrapolations as a result of understanding that is lacking in nuance. Another author who is relevant to this conflict is Georg Simmel, writer of The Stranger, an essay in which Simmel describes a new sociological category known as the stranger, who is different from the wanderer, and the outsider. The stranger is a person who is in the group but not of the group and are in a way perceived as more objective judges of the group they belong to.[9] This category of the stranger can be seen in various ways, often filling the role of a trader, but when looking at the ethnography reported in Miner’s article, the role of the stranger is also present. In the article, the ethnographer who reports on the Nacirema is more than a stranger, he is an outsider. He does not belong in any way to the culture he is representing and thus does not provide an objective account.[10] This is an important idea to keep in the back of the mind when looking at huacas and the Cusco Ceque and the Extirpation as both of these were recorded by the Spanish, not the indigenous people who suffered through them.

Looking at the sources in the next section, the primary sources that they are based on are largely Spanish accounts. These accounts range in authorship, including friars, explorers, conquistadors, archivists, chroniclers, and more, and while some of the writers of the documents were of partial indigenous ancestry, they also found themselves in the upper echelons of colonial hierarchy through wealth and status. The issues with the commonality in origin found throughout the documentation of the conquest and what preceded it can be analyzed through the dual perspectives of Miner and Simmel in Body Ritual Among the Nacirema and The Stranger, respectively. Looking at Miner’s parody of anthropologists who begin to study and record ethnographic evidence without a real understanding of the societies they are studying, the issue of representation in anthropology comes to light, and when contrasted with Simmel’s opinions regarding the stranger as a sociological category, an interesting issue is found. Miner’s article shows the dangers of treating cultures as alien, as when treated this way, they often end up represented as such, and while Simmel advocates for the inclusion of the stranger in the community, the stranger as a category is, notably, never completely of the group.[11] The issue therein with these frameworks of anthropology, however is that they problematize the study of a group if it is done by a person belonging to that group, and in the field of anthropology, the demographics studying a certain group are often two: people belonging to that group, and white people. Problematizing the introspective analysis of anthropologists goes against the concepts of inclusion and diversity by excluding anthropologists of color and leaving the “objective” analysis to the white, Western majority of the field.

An important historical context of the broader colonial struggle of Latin America is presented by Eduardo Galeano in his book, Open Veins of Latin America. In his book, Galeano discusses the reasons that Latin America’s history is fraught with so much conflict despite its size and wealth, and in doing so presents very useful insight into what the conquest’s mythos really depended upon. “The epic of the Spaniards and Portuguese in America combined propagation of the Christian faith with usurpation and plunder of native wealth.”[12] With this quote, the intention of the Iberian conquest of Latin America is revealed and reinforced. While this paper will primarily focus on the religious aspects of imperial expansion, the combination of this with the taking of indigenous wealth is crucial. While Andean indigenous peoples were subject to the Spanish Empire’s religious persecution, they also found themselves working to produce wealth for Spain, with both systems feeding each other.

The Case – Inca and Spanish Imperialism: A Study of Continuity

To understand these two forms of empire building and their subsequent forms of resistance, in the Andes, it must first be understood what exactly the trends were. Huacas are a crucial constant of Andean culture, religion, and politics. They are objects representing something revered. Huacas take on a significant role in Andean religion due to their varied definitions, significances to different groups, and natures. They were natural objects that stood out of the ordinary, and as the Spanish missionary Bernabé Cobo later added, they were also designated places of prayer and sacrifice, with some being related to Gods, and some acting as divine figures in and of themselves.[13] Some examples of huacas include the mountain overlooking the Inca capital and modern city of Cusco, Huanacaure, which holds significance in Inca mythology as the place where a brother of Manco Capac, the mythical first Sapa Inca, was turned to stone.[14] Huacas also included springs, caves, roads, trees, etc. essentially anything in nature that connected humans with the spiritual/supernatural world.[15]

Figure 1: Drawing by Felipe de Guaman Poma of Topa Inca Yupanqui, Sapa Inca, a gathering regional huacas under Huanacaure, mountain seen on the left and the temple at its peak at the top left.[16]

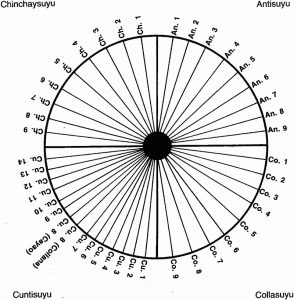

Another key aspect of huacas is their importance to local peoples, acting as or representing patron deities of local ethnic groups and often holding near equal importance to other Pan-Andean Gods/figures such as the Sun and the Earth. The Inca adopted huacas into their broad state religion using the Cusco Ceque System, a ritual system that divided the Inca empire with ritual lines radiating out of the central Inca temple of the sun in the capital city of Cusco, called the Coricancha, into the rest of the Empire. Through the system’s use, the Inca exerted political power upon smaller polities and provinces, incorporating them into the Empire on a spiritual and physical level.[17]

This archaeological basis of understanding is found in Brian Bauer’s book, The Sacred Landscape of the Inca: The Cusco Ceque System. Bauer’s description of huacas and the Ceque System comes from various accounts written in the colonial period by missionaries, chroniclers, and other sources, all of which are written by Spaniards. It is important to note this as there is a lack of pre-colonial Inca records because the Inca did not have a written language, and instead used quipus, complex devices made of knotted string which recorded “dates, statistics, accounts, and even abstract ideas.”[18]

Figure 2: Quipu from the collection at the Museum of Colchagua in Santa Cruz, Chile.

Image by Jack Zalium.[19]

The key similarity that is seen between Inca and Spanish state and empire-building is the use of religion as a state builder through the forced imposition of an imperial religion, the Inca religion in the pre-colonial, and Catholicism in the colonial. While there are differences in the way that the Inca and Spanish sought to impose religious rule, the most important difference between the two approaches was the familiarity held between the imperial religions and the religions of the subjects. In the Andes, huacas have a long history, predating the Inca Empire by thousands of years.[20] Huacas were already, and continue to be, integral parts of Andean culture and religion and, acting as religious monuments, they hold incredible power as symbols of the land and the people who inhabit that land. The Inca knew this and sought to exert control over conquered peoples by exerting control over their huacas through the Cusco Ceque System, the ritual line system that divided the Empire through connect-the-dot-styled lines. The System’s lines, known as Ceques, were drawn by connecting huacas in the Empire to form long geographic routes that connected communities to each other and to the Coricancha, the imperial religion’s centerpiece, in both the material and spiritual worlds.[21] These lines adopted conquered communities into the Inca system, made them subject by lowering their religious figures in the symbolic hierarchy.

Figure 3: “The Cusco ceque system. Chinchaysuyu, Antisuyu, and Collasuyu contained nine [Ceques] each; Cuntisuyu contained 15 lines.”[22]

In Amy Scott’s article Sacred Politics: An Examination of Inca Huacas and their use for Political and Social Organization, Scott elaborates upon the way that religious organization influenced social organization. “Alliances with other groups near Cusco were strengthened through the inclusion of outside members into the Inca capital but most importantly through the incorporation of outsider huacas into the Cusco Ceque System.”[23] The Inca’s incorporation of huacas into the Cusco Ceque influenced not only into conquered peoples but allies, especially in the practices that huacas promoted, like making sacrifices. As allies made sacrifices to their now Inca adjacent huacas, they also made sacrifices to the Coricancha, and to the Inca pantheon, and thus put themselves into a servile position.[24]

The power dynamics between huacas is also seen in exchanges between the Sapa Inca and huacas in two different sources. Firstly, in R. Alan Covey’s chapter The Inca Empire, Covey tells the story of Atahuallpa, the Sapa Inca at the time of Francisco Pizarro’s arrival, a huaca that acted as a provincial oracle, and the priest who spoke for the huaca. In an attempt to silence the huaca, which criticized Atahuallpa’s bloody policies, Atahuallpa destroyed the huaca, a sacred stone, and its priest, who spoke for it.[25] Atahuallpa then had the stone and the priest’s remains burnt and thrown to the wind from a mountaintop, dispersing and ridding himself of the critical, destroyed power.[26] Another image presented in Lisa Trever’s Idols, Mountains, and Metaphysics in Guaman Poma’s Pictures of Huacas Sapa Inca gathering regional huacas accused of halting precipitation under Huanacaure, an enormous mountain with a huaca representing the Inca kings and founders.[27] Again, the power held by the Sapa Inca through his position as well as his connection to other powerful huacas is seen exerted upon huacas lower in the hierarchies. Cowering in fear of both the Sapa Inca and Huanacaure, the huacas lower themselves, and find themselves forced to follow the Inca’s orders.

Before discussing the Spanish Empire’s religious organization, it is important to talk about the continuities in social and economic organization between the pre-colonial and colonial period. The political organization of Spanish settlements was taken right out of the indigenous rulebook. The República de Indios system of governance instituted by the Spanish included a cabildo, a town council modeled after the Spanish institution, governing with a governor, “sometimes a cacique or dynastic lord descended from precolonial kings or rulers.”[28] In addition to the governor sometimes being the next out of a pre-colonial line of succession, the cabildo system was, in practice, “was merely a new veneer over an ancient system of government by village elders.”[29] While all the Repúblicas were under overarching Spanish control, the experience of most indigenous people in the Andes–and broader Latin America–before and after the colonial period did not change much, with their ayllus, the Quechua name for the community unit in the Andes, being organized very similarly to the way it was prior to the invasion.

Looking at economic organization in the Andes, the Spanish also took notes on Inca labor systems. “Patterned on the [Inca] mit’a, or ‘turn,’ system, the Spanish mita demanded adult indigenous men to work for extended periods…”[30] The mit’a essentially acted as a tax that could be directly invested into maintaining the empire through both wealth acquisition as well as infrastructure maintenance, all the while allowing for the men who served to still keep their families and livelihoods in good order.[31] The Spanish change to the system, however involved in turning the tribute periods longer and investing labor into the most lucrative endeavors, namely mining in the Andes, and most notably at the mining city of Potosí.[32] Since the Spanish modeled so much of their Andean imperial processes after systems that predated them in the region, they had less heavy lifting to do in creating new order, and instead could focus on prioritizing conversion and profits rather than organizing the systems needed to support wealth gathering.[33]

While in the pre-colonial period, we see the collision of shared cultural spiritual concepts into one imperial religion, in the colonial, two worlds collided. In Cowie’s chapter Peruvian Sheep, a form of syncretism and religious combination can be seen in various images. The murals of the last supper with Jesus serving cuy and the Virgin Mary depicted wearing a mountain-like cloak with frolicking Andean wildlife along it show how Andeans found a way to continue their old beliefs, and more importantly, how religion changed to accommodate indigenous beliefs and to welcome them.[34] Showing an indigenous looking Jesus serving cuy, a traditional Andean food, to his apostles at the last supper is a clear example of how Catholicism had to adapt to include Andean realities for the purposes of attracting Andean converts. In the painting of the Virgin Mary, her depiction as a mountain is very important. While the red cloak she wears contains images of llamas, viscachas, and vicuñas, the key difference is the broader symbolism communicated by the mountain-ness of her cloak and what seems to be the Sapa Inca depicted. By combining the Virgin Mary with the mountains of the Andes, the persistence of indigenous spirituality can be seen, even if the religions themselves are not practiced.

Figures 4 & 5: Marcos Zapata, “The Last Supper.”[35] Anonymous, “La Virgen del Cerro.”[36]

Another aspect of the colonial period was the Extirpation, the project undertaken by the Spanish to eradicate indigenous religion in the Americas. While the Spanish already had the Inquisition to make better Catholics, in 1571, Philip II decided that the indigenous peoples of the Americas could not be subject to the Inquisition due to their poor understanding of the faith. The Extirpation was far less organized and broadly implemented than the Inquisition, but it still did much to erase indigenous practices by destroying the “instruments of idolatry” and “the false gods, the ancestors’ remains, and the sacrificial materials.”[37] Two key documents, which are explored further later, include the Father Francisco de Avila’s Huarochirí Manuscript and Father Pablo José de Arriaga’s The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru, the former an originally Quechua document recording Andean mythology, and the latter a didactic text instructing extirpators on how to go about ridding Indigenous Andeans of their beliefs.[38]

The Inquisition and Extirpation complemented each other through their persecution of different groups and through different means. The Inquisition in the Americas was not as violent as the Extirpation, and it was largely dominated by judicial reform and tax codes being enforced as opposed to the Extirpation.[39] The Extirpation, on the other hand, was more varied in its approaches, some of which were rather violent; Mills states that, “…nothing was thought to be more instructive for the Indians, or more symbolic of their spiritual fate, than the religious spectacles that featured the destruction of their forbidden cults.”[40] This use of spectacles to destroy religion is very similar to the way that the Sapa Inca would exert his power over local huacas who disrespected him in various ways, and presents a very similar story to the one told in the pre-colonial period. Despite this, these beliefs persisted long after the Extirpation and continue to be practiced today simultaneously with Catholicism in the Andes.

Analysis – Records of Changes and Continuities

The primary goal of this paper is to determine how much Spanish influence changed the Andes, and while the first inclination I had was to claim there was a dramatic change, this seems to not be quite the case. While it is certainly true that the Spanish changed the Andes, they also didn’t. The collision both changed everything and not much at all, which can be seen in the economic, social, and religious continuities between the pre-colonial and colonial periods. However, the Spanish impact did largely write indigenous people out of the archives as is seen throughout the theoretical framework and the case. Just as Galeano wrote in Open Veins of Latin America, the Spanish came with the intention of pillaging and converting, but with a much larger emphasis on the pillage.[41] The pillaging and economic exploitation done by the Spanish ranges in efficacy, but regardless, they managed to extract much of Latin America’s wealth, and what made this process much easier was the high level of continuity they maintained in their new empire. Despite this, while the mita and the República de Indios both were continuities of stability, the continuity of conflict is also present in the religious world. The proliferation of conversion and the destruction of indigenous spirituality, presents a paradox of power seen through the historical record, especially in the sources that are used in the modern era to analyze and understand the Inca.

When looking at colonial records that sought to record the Inca, such as the Huarochirí Manuscript or Father Pablo José de Arriaga’s The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru, it is found that the drive behind recording is to better erase, better exploit, or glorify the aforementioned erasure and exploitation. These primary sources, both record key points in the Extirpation, as the Huarochirí Manuscript was written to understand Inca religion and then erase it, and The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru was written as a didactic text, giving instruction to priests on how best to get rid of Andean spiritual beliefs.[42] In the description of the item provided by the John Carter Library at Brown University, it is stated that, “in spite of its brutality, the book is a rich trove of Andean ethnography.”[43] This repetition of brutality in the attempts to understand the Inca presents just how successful the Spanish were in empire building, doing something that the Inca didn’t. They fundamentally altered the future perceptions of the culture conquered by approaching the process as a conquest and not settlement. This approach, economically motivated as well as religiously motivated, sought to legitimize conceived notions of racial and cultural superiority held by the Spanish as well as to allow them to exploit the Andean peoples. Due to their inherent advantage in the form of a written language, the Spanish created the records needed to understand the Inca, never giving the Inca the opportunity. Acting much like the diseases and rampant slavery that wiped out the grand majority of the indigenous populations in the Americas, the linguistic and cultural attributes of the Spanish helped them to conquer not only the Andes and its inhabitants, but the idea of the Andes in the minds of the great many who would come to study it.[44]

Conclusion – Andean Spirituality in the Modern Day

While it seems that the Andes and Andean people were greatly changed and erased by Spanish rule, it is important to note the resistances seen to ideological colonial rule in the Andes. The proliferation of indigenous Andean iconography in Catholic icons is a strong indicator of this, as well as the fact that huacas continue to be worshipped in the modern day as part of Christian ceremonies and on their own. For example, in Peru, the festivals of Inti Raymi and Pachamama Raymi, which celebrate the Andean Sun and Earth deities, Inti and Pachamama, are still celebrated and are important cultural touchstones in Cusco and the surrounding areas.[45] While these festivals’ present-day importance is diminished as being more of a touristic spectacle, their existence in the modern day is a clear signifier that they still hold importance and cultural relevance after hundreds of years of colonial and post-colonial erasure.[46] The other notable aspect of both of these ceremonies is that the knowledge needed to be an Andean priest has also been passed down through the ages.[47] The knowledge being passed down is yet another example of how important and persistent Andean spirituality is, and by extension Andean people are.

In Bolivia, another country in the Andes where Andean religious beliefs persist, many Catholic ceremonies are mixed with Andean religion, having both Catholic priests and indigenous elders in the same plaza on holy days.[48] Bolivia, however, is beginning to see conflict between evangelicals and Andean-Catholics, with the syncretic symbiosis that has existed for years in the country being challenged by evangelicals, who in Latin America “don’t necessarily focus on a denomination.”[49] This conflict between Andean-Catholics and evangelical Christians, which seeks to erase an indigenous presence in both governance and the governed, is reminiscent of Extirpation ideals and interestingly pushes the envelope of tolerance, with the status quo of syncretism being disturbed by a new evangelical wave of discontent.

These forms of persistence and oppression reinforce the power and capabilities of the indigenous Andean population that has faced systemic erasure, exploitation, and colonial persecution for centuries into the present day. From the colonial to the modern period, Christian fundamentalism has sought to erase Andean religion and culture, which stands in contrast to a more colonial and European Christian culture. Despite this, resistance and persistence show that the Andean region is one of many places where Spanish colonialism did a lot and very little simultaneously. Its conflicts in ideologies and outcomes exemplify the simultaneous and paradoxical relationship between erasure and persistence that indigenous cultures have in Latin America.

Endnotes

[1] Cartwright, “Inca Government.”

[2] Restall and Lane, “Castile and Portugal.”

[3] Britannica, “Inca People – History, Achievements, Culture, & Geography”; Shah, “Language, Discipline, and Power.”

[4] Ali, “‘Warmikuna Quñusqa Kasun’ or ‘Women, We Are United’; Indigenous Feminist Rap Music as a Form of Resistance.”

[5] Ali.

[6] Ali.

[7] Bauer, “The Original Ceque System Manuscript”; Ali, “‘Warmikuna Quñusqa Kasun’ or ‘Women, We Are United’; Indigenous Feminist Rap Music as a Form of Resistance”; MacCormack, “Prologue,” 4.

[8] Miner, “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema.”

[9] Simmel, “The Stranger.”

[10] Objectivity in cultural studies is a large debate. Some camps argue that objectivity is inherently relative to the culture of the anthropologist or ethnographer, and thus impossible, and some argue that objective accounts are possible. Anthropology as a discipline also has a fraught history of being leveraged against communities of color and marginalized peoples. For the purposes of this paper, objective will be used as, however I do acknowledge that it is an imperfect term.

[11] Miner, “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema”; Simmel, “The Stranger.”

[12] Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, 24.

[13] Bauer, “Introduction.”

[14] Bauer, “Pacariqtambo and the Mythical Origins of the Inca.”

[15] Bauer, “Huacas.”

[16] Trever, “Idols, Mountains, and Metaphysics in Guaman Poma’s Pictures of Huacas.”

[17]Bauer, “Introduction.”

[18] Cartwright, “Quipu.”

[19] Zalium, Khipu.

[20] Scott, “Sacred Politics.”

[21] Scott.

[22] Bauer, “The Cusco Ceque System as Shown in the Exsul Immeritus Blas Valera Populo Suo.”

[23] Scott, “Sacred Politics,” 29.

[24] Scott, “Sacred Politics.”

[25] Covey, “The Inca Empire.”

[26] Covey.

[27] Trever, “Idols, Mountains, and Metaphysics in Guaman Poma’s Pictures of Huacas.”

[28] Lane and Restall, “Plunder and Production,” 77.

[29] Lane and Restall, 77.

[30] Lane and Restall, 82–83.

[31] Lane and Restall, “Plunder and Production”; Covey, “The Inca Empire.”

[32] Lane and Restall, “Plunder and Production.”

[33] Lane and Restall; Covey, “The Inca Empire.”

[34] Cowie, “Peruvian Sheep.”

[35] Zapata, The Last Supper.

[36] Anonymous, La Virgen Del Cerro.

[37] Mills, Idolatry and Its Enemies, 267.

[38] Salomon, Urioste, and de Avila, The Huarochirí Manuscript; de Arriaga and Keating, The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru.

[39] Nesvig, “‘I Shit on You, Sir’; or, A Rather Unorthodox Lot of Catholics Who Didn’t Fear the Inquisition.”

[40] Mills, Idolatry and Its Enemies, 267.

[41] Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent.

[42] Brown University John Carter Brown Library, “José de Arriaga, Extirpación de La Idolatría Del Pirú. Lima, 1621.”

[43] Brown University John Carter Brown Library.

[44] Ali, “‘Warmikuna Quñusqa Kasun’ or ‘Women, We Are United’; Indigenous Feminist Rap Music as a Form of Resistance”; Reséndez, “Caribbean Debacle.”

[45] peru.travel, “Inti Raymi: The Most Important Festival of the Inca Empire”; PeruRail, “Day of Mother Earth – Pachamama Raymi.”

[46] peru.travel, “Inti Raymi: The Most Important Festival of the Inca Empire”; PeruRail, “Day of Mother Earth – Pachamama Raymi.”

[47] PeruRail, “Day of Mother Earth – Pachamama Raymi.”

[48] McCombs, “The Bible vs Andean Earth Deity.”

[49] McCombs; openDemocracy, “The Bible Makes a Comeback in Bolivia with Jeanine Añez”; Sesin, “Bolivia’s New Leader, Religious Conservative Jeanine Añez Chavez, Faces Daunting Challenges”; Gutiérrez, “Pious, Assertive, and ‘mother of All Bolivians’.”

Ali, Jasmine. “‘Warmikuna Quñusqa Kasun’ or ‘Women, We Are United’; Indigenous Feminist Rap Music as a Form of Resistance,” May 19, 2023. https://pressbooks.claremont.edu/las180genderanddevelopmentinlatinamerica/chapter/jasmine-ali/.Anonymous. La Virgen Del Cerro. 1720.Arriaga, Pablo Joseph de, and L. Clark Keating. The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru. University Press of Kentucky, 1968. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt130js2q.Bauer, Brian S. “Huacas.” In The Sacred Landscape of the Inca, 23–34. The Cusco Ceque System. University of Texas Press, 1998. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/708655.7.———. “Introduction.” In The Sacred Landscape of the Inca, 1–12. The Cusco Ceque System. University of Texas Press, 1998. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/708655.5.———. “Pacariqtambo and the Mythical Origins of the Inca.” Latin American Antiquity 2, no. 1 (1991): 7–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/971893.———. “The Cusco Ceque System as Shown in the Exsul Immeritus Blas Valera Populo Suo.” Ñawpa Pacha 36, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00776297.2016.1169717.

———. “The Original Ceque System Manuscript.” In The Sacred Landscape of the Inca, 13–22. The Cusco Ceque System. University of Texas Press, 1998. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/708655.6.

Britannica. “Inca People – History, Achievements, Culture, & Geography,” October 24, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Inca.

Brown University John Carter Brown Library. “José de Arriaga, Extirpación de La Idolatría Del Pirú. Lima, 1621.” Accessed December 2, 2023. https://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/exhibitions/peru/peru/ch_arriaga.php.

Cartwright, Mark. “Inca Government.” World History Encyclopedia, October 21, 2015. https://www.worldhistory.org/Inca_Government/.

———. “Quipu.” World History Encyclopedia. Accessed November 26, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/Quipu/.

Covey, R. Alan. “The Inca Empire.” In The Oxford World History of Empire: Volume Two: The History of Empires, edited by Peter Fibiger Bang, C. A. Bayly, and Walter Scheidel, 0. Oxford University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197532768.003.0025.

Cowie, Helen. “Peruvian Sheep.” In Llama, 50–81. Animal. Reaktion Books, 2017. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/L/bo26297639.html.

Galeano, Eduardo. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. Translated by Cedric Belfrage. Monthly Review Press, 1974.

Gutiérrez, Fabiola. “Pious, Assertive, and ‘mother of All Bolivians’: The Political Narrative of President Jeanine Áñez.” Translated by Liam Anderson. Global Voices, August 10, 2020. https://globalvoices.org/2020/08/10/pious-assertive-and-mother-of-all-bolivians-the-expensive-political-narrative-of-president-jeanine-anez/.

Lane, Kris, and Matthew Restall. “Plunder and Production.” In The Riddle of Latin America, 69–83. Cengage, 2012.

MacCormack, Sabine. “Prologue: Themes and Arguments.” In Religion in the Andes, 3–14. Vision and Imagination in Early Colonial Peru. Princeton University Press, 1991. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1fkgd0m.6.

McCombs, Brady. “Bolivia Religious Debate: The Bible vs Andean Earth Deity.” AP News, January 25, 2020. https://apnews.com/article/caribbean-ap-top-news-international-news-la-paz-lifestyle-5b2c57adfe878163be4b0288890d7bf3.

Mills, Kenneth. Idolatry and Its Enemies: Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation, 1640-1750. Princeton University Press, 1997. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv39x67x.

Miner, Horace. “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema.” American Anthropologist 58, no. 3 (1956): 503–7. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1956.58.3.02a00080.

Nesvig, Martin Austin. “‘I Shit on You, Sir’; or, A Rather Unorthodox Lot of Catholics Who Didn’t Fear the Inquisition.” In Promiscuous Power, 80–101. University of Texas Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7560/315828-006.

openDemocracy. “The Bible Makes a Comeback in Bolivia with Jeanine Añez.” openDemocracy. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/democraciaabierta/qui%C3%A9n-es-jeanine-a%C3%B1ez-y-por-qu%C3%A9-desprecia-los-pueblos-ind%C3%ADgenas-de-bolivia-en/.

PeruRail. “Day of Mother Earth – Pachamama Raymi.” PERURAIL, August 15, 2016. https://www.perurail.com/blog/day-of-mother-earth-pachamama-raymi/.

peru.travel. “Inti Raymi: The Most Important Festival of the Inca Empire,” July 9, 2020. https://www.peru.travel/en/masperu/inti-raymi-the-most-important-festival-of-the-inca-empire.

Reséndez, Andrés. “Caribbean Debacle.” In The Other Slavery, 1st ed., 13–40. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Restall, Matthew, and Kris Lane. “Castile and Portugal.” In Latin America in Colonial Times, 20–35. Cambridge University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108236829.

Salomon, Frank, Jorge Urioste, and Francisco de Avila. The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion. 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.03635.

Scott, Amy. “Sacred Politics: An Examination of Inca Huacas and Their Use for Political and Social Organization.” Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology 17, no. 1 (June 24, 2011). https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/totem/vol17/iss1/11.

Sesin, Carmen. “Bolivia’s New Leader, Religious Conservative Jeanine Añez Chavez, Faces Daunting Challenges.” NBC News, November 14, 2019. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/bolivia-s-new-leader-religious-conservative-jeanine-ez-chavez-faces-n1082426.

Shah, Priya. “Language, Discipline, and Power: The Extirpation of Idolatry in Colonial Peru and Indigenous Resistance.” Voces Novae 5, no. 1 (April 26, 2018). https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol5/iss1/7.

Simmel, Georg. “The Stranger.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited and translated by Kurt H. Wolff, 402–8. Glencoe, Illinois: Free Press, 1950.

Trever, Lisa. “Idols, Mountains, and Metaphysics in Guaman Poma’s Pictures of Huacas.” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 59–60 (March 2011): 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1086/RESvn1ms23647781.

Zalium, Jack. Khipu. May 20, 2011. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/kaiban/5757555504/.

Zapata, Marcos. The Last Supper. 1753.