1 Comparing Accessible Opportunities for Women of Color in American and Costa Rican Healthcare Systems

Isabella Fuenzalida

Introduction

The U.S. is one of the lowest ranked countries for generalized quality healthcare, accessibility and efficiency, despite the assumption by the West that they have the most advanced and effective healthcare system. Using data from the United Nations, World Health Organization and World Bank, the Bloomberg Index of Countries with the Most Efficient Healthcare Around the World ranked the U.S. 50th place out of 55 countries (Miller & Lu 2018). However, countries that are perceived to be less developed than the US have much better healthcare that is significantly higher rated. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) includes 38 countries with some of the biggest economies ranging from the U.S. and the U.K. to smaller countries such as Costa Rica or Portugal. Evidence shows compared to other OECD countries, Costa Rica performs better than the OECD average on 75% of health status indicators, 56% risk factor indicators, 67% quality of care key indicators, 40% of accessibility indicators, and 17% of health system resource indicators (OECD 2023). Health status indicators include life expectancy, preventable mortality, diabetes prevalence, or self-ranking overall health status as “bad” or “very bad.” Indicators of risk factors include smoking prevalence, alcohol consumption, obesity prevalence, and deaths from air pollution. Indicators of quality of care include both acute and primary care ranging from avoidable admissions, safe prescribing, and preventative care. Access to care is evaluated by percent of the population covered, availability of financial coverage compared to out of pocket spending or mandatory payment. The U.S. on the other hand performs only better than the OECD average on 29% of health status indicators, 33% risk factor indicators, 56% quality of care key indicators, 57% of accessibility indicators, and 46% of health system resource indicators which for the most part is far less compared to Costa Rica (OECD 2023). The low U.S. ranking compared to other OECD countries demonstrates a flawed healthcare system overall; but in a country that supposedly advocates for the “rights of every citizen,” this system is rooted in institutional racism that perpetually discriminates against people of color (POC). The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) reports “racial and ethnic minorities receive lower-quality health care than white people—even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable” (NAM 2003). The inequities extend beyond race and ethnicity, to severely affect women of color. Black women face greater challenges in “accessing affordable and quality healthcare, including a lack of health insurance, higher medical debt, longer travel times to hospitals” and are “more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to die from cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke, lupus, and several cancers” (McKoy 2023). Most of the existing literature outlines why Costa Rica’s healthcare system is generally more advanced and efficient than the US, yet there is a severe lack of research that centralizes a group in desperate need for healthcare equity, women of color (WOC). My research specifically seeks to understand what US policies are discriminatory towards WOC, how this affects accessibility, and if Costa Rica’s success promotes higher quality care for this minority group. The goal of this research is to decentralize the colonial mindset and Western superior thought as well as showcase how the US can directly learn from systems that have long been established and are more successful in ways that we are not.

Theoretical Framework

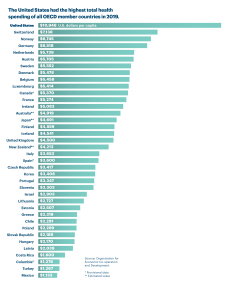

In the US, the healthcare system is rooted in capitalism and inadequate spending. According to The Commonwealth Fund, the US spends “nearly twice as much as the average OECD country… yet has the lowest life expectancy and highest suicide rates among all the nations” (Abrams & Tikkanen 2020). These statistics illuminate the failure of the US healthcare system generally, but even more so for people of color (POC). Although this is a significant problem in the US, Latin American countries including Costa Rica face equity issues for POC as well. In a report by the Pan American Health Organization about the region, director Carissa F. Etienne states, “health inequities faced by Afro-descendant people occur in a context of discrimination and institutional racism, often exacerbated by gender inequalities,” making it even more challenging to survive as a woman of color. A predominant analytical framework integral to this essay is the work of Kimberle Crenshaw’s Intersectionality Theory which explains various social identity groups experience oppression and the hierarchy of power based on the overlapping of different groups. The Coloniality of Gender by Maria Lugones can be used to connect the gender and race inequalities rooted in U.S. medical treatment. Lugones offers an explanation for the large equity gap faced by WOC, as gender was only applied to white (bourgeois) women whereas women of color were seen as female but not as humans. She employed the framework of the Coloniality of Power by Anibal Quijones, which distinguishes humans vs. non-humans under the hierarchy of power. Lugones further observes the indifference between men of color who have accepted the mentality of the colonizer particularly when theorizing ‘global domination’ which interferes with any justice movement for WOC. In fact, the Santa Cruz Feminist of Color Collective claims the term “women of color” promotes a “larger coalitional identity.” The collective movement is composed of humans fighting for equity and justice, so why is this group still fighting for basic rights to healthcare?

This research aims to fill the literature gap surrounding this coalitional identity and promote ways to improve treatment measures as a whole. Costa Rica’s long-established public services serve to illustrate the notion that there are things the US has yet to achieve, despite the common belief that Western thought is the most advanced. Sarah Hoagland’s article Aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge informs readers that much of Western belief is a direct result of colonization. In this paper, I apply this framework to show that the ‘coloniality of knowledge’ has led to disregarding the success of other structures to adapt potential lessons that could be applied in the US. What each of these foundational texts have in common is the authors’ call for Western figures to listen to those who are suffering as a direct result of their oppressive systems and to those who may have done it first. That is exactly what this essay strives to do by using the Sociological Imagination. This concept helps us try to understand “larger historical scenes in terms of their meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals” (2). C. Wright Mills proposed the concept to question, “What kinds of ‘human nature’ are revealed in the conduct and character we observe in this society in this period?” This essay uses the Sociological Imagination to dismantle the Coloniality of Knowledge and focus on the efficiency of Costa Rica’s organization, as well as what U.S. policies enable discrimination. To do so I ask, “In what ways does the US healthcare system compare to Costa Rica’s healthcare system to increase accessibility for women of color?”

This research aims to fill the literature gap surrounding this coalitional identity and promote ways to improve treatment measures as a whole. Costa Rica’s long-established public services serve to illustrate the notion that there are things the US has yet to achieve, despite the common belief that Western thought is the most advanced. Sarah Hoagland’s article Aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge informs readers that much of Western belief is a direct result of colonization. In this paper, I apply this framework to show that the ‘coloniality of knowledge’ has led to disregarding the success of other structures to adapt potential lessons that could be applied in the US. What each of these foundational texts have in common is the authors’ call for Western figures to listen to those who are suffering as a direct result of their oppressive systems and to those who may have done it first. That is exactly what this essay strives to do by using the Sociological Imagination. This concept helps us try to understand “larger historical scenes in terms of their meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals” (2). C. Wright Mills proposed the concept to question, “What kinds of ‘human nature’ are revealed in the conduct and character we observe in this society in this period?” This essay uses the Sociological Imagination to dismantle the Coloniality of Knowledge and focus on the efficiency of Costa Rica’s organization, as well as what U.S. policies enable discrimination. To do so I ask, “In what ways does the US healthcare system compare to Costa Rica’s healthcare system to increase accessibility for women of color?”

The Case

Inequitable Healthcare: The United States

Most well-established institutions in the US are built on racism and discrimination. Moreover, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic made the disparities built within modern healthcare policy strikingly clear. According to Ruqaiijah Yearby, Brietta Clark, and José F. Figueroa of the Journal of Health Affairs, U.S. healthcare administration is built to advantage upper-class white populations, leaving minority populations to suffer with the challenge of accessing high-quality, equitable care. This goes as far back as the Jim Crow era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 1946 Hospital Survey and Construction Act allowed for the construction of public hospitals and mandated the availability of these services to all regardless of race, yet still racially separate and unequal facilities were built. Despite facilities claiming to be equal, minorities were still unable to pay for insurance or necessary services. The federal government’s structural racism enabled

“a number of laws that not only supported the occupational segregation of racial and ethnic minority workers in low-wage jobs in the service, domestic, and agricultural industries but also excluded racial and ethnic minority workers from laws that increased wages and offered protections for collective bargaining that resulted in paid sick leave and health insurance for other workers” (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022).

The laws established during this era still have effects today that burden minority groups and simultaneously benefit upper-class White populations. A modern two-tier healthcare system was created as a result of racist laws and policies. Despite Medicaid expansion, lawmakers made it optional to pass in every state as well as incorporate eligible restrictions that disproportionately affect people of color. Amongst challenges of accessibility, high-quality care is rare. The hospitals and care centers made available for marginalized populations “tend to score lower on patient satisfaction surveys, underperform on evidence-based metrics, and report higher rates of adverse safety events and complications” (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa 2022).

Similarly, Crenshaw’s Intersectionality framework highlights the challenges particular to the experience of the intersection between race and gender. Health inequities are exacerbated for women of color. A 2021 study published in the Journal of Women’s Health expands on the various factors that explain why Black women in the US experience discrimination disproportionately compared to their white female counterparts and Black male peers including social, educational, and economic determinants. Research suggests chronic exposure to stressors such as systematic oppression, more frequent instances being head of household, and higher unemployment and poverty rates across the lifespan “contribute to the weathering of the health of Black women, increasing their allostatic load and, consequently, compromising their reproductive and mental health.” Environmental factors such as decreased ability to benefit from living in a politically, culturally, and socioeconomically White-dominated society increase low sleep quality, resulting in “activation of the chronic stress response and resultant elevations in cardiometabolic disease.” Racial and sexual genetics based on decades of low-quality treatment make Black women more likely for blood, bleeding, cardiovascular disorders, and mortality including maternal mortality (Chinn, Martin, & Redmond 2021). Despite efforts to improve these conditions by lawmakers and social justice advocates, what these two articles demonstrate is the integration of structural racism built within the U.S. institution for decades.

A Successful Healthcare System: Costa Rica

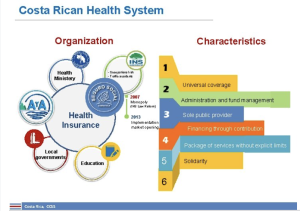

Despite having the lowest poverty rate in Central America, Costa Rica is developing a plan to reform the country, one aspect being their highly successful healthcare organization. Costa Ricans are some of the healthiest people in the world, with “reduced incidence of cardiovascular diseases, coupled with a low prevalence of obesity” (Rosero-Bixby 2008). Further, in 2018 the United Nations Development Program ranked Costa Rica in the “Very High” group for education, life expectancy, and under five mortality rate. For example, the mean life expectancy for the countries in the “Very High” category was 79.5, while Costa Rica earned an 80. (Campbell Barr & Marmot 2020). The Pan American Health Organization reports Costa Rica’s healthcare system success is a result of their system being built “on solidarity… and invests in the well-being of its people, not using the military against them.” Costa Rica took initiative in their healthcare system starting in the early-nineteenth century to the twentieth century, around the time when the US created the healthcare policies that still have lasting effects on minority groups. The Ministry of Health was founded in 1922 while the Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social was founded in 1941. Despite the country’s numerous struggles in leadership, the expansion of the role of the Ministry and Caja in primary health care created “the building blocks for a strong system preventing disease and promoting health” (Prado, Rodríguez & Salas 2019). In 1949, they passed a new constitution that included a decision to cease investment in national defense allowing more investment in health, welfare, and education, created a universal health system financed by the State, employers and workers and generated opportunities to lift important sectors of the population out of poverty, allowing them to have basic sanitary conditions that increase their possibilities to live longer and in better conditions. (Campbell Barr & Marmot 2020).

Further, in 1994, they reformed their system and implemented a model of basic integrated healthcare teams. This new model was created to “serve a geographically empaneled population—that could provide the four critical functions of primary health care: first-contact access, comprehensiveness, continuity, and coordination” (Pesec, Ratcliffe, Karlage, Hirschhorn, Gawande, & Bitton 2017). With all of these new models, Costa Rica is able to successfully decrease inequality gaps for Afro-descendant and Indigenous populations. In a cross-sectional study in 2023, sixteen national surveys were available between 2011-2020. Representative data on 221,989 women and 152,983 children from Latin American and Caribbean countries was surveyed for more than twelve health-related outcomes including

“the composite coverage index, demand for family planning satisfied with modern methods, antenatal care, skilled attendant at birth, postnatal care for the mother, full immunization coverage, stunting prevalence among under-five children, tobacco use by women, adolescent fertility rate, and under-five and neonatal mortality rates” ( Mujica, Sanhueza, Carvajal-Velez, Vidaletti, Costa, Barros, & Victora, 2023).

What they found is some countries still have room for improvement such as Guyana, Honduras, Peru, and Suriname. However, for countries like Argentina, Costa Rica, and Cuba, inequalities were small for most indicators. The success of Costa Rica’s focus on the well-being of their citizens is highly prevalent and will continue to grow.

The Analysis

The US is in a higher position of power above many developing countries because it is heavily industrialized and prioritizes economic success, with a privileged position to spend the most out of all OECD nations. However, if they took a moment to pay attention to and learn from the successful strategies of those countries that might be lower on the hierarchy of power, they may be more successful at promoting equity. According to two researchers from the Universidad de Costa Rica, “people lower on the hierarchy in Costa Rica live longer than people in the equivalent position in the United States” (Rosero-Bixby & Dow 2016). So how could the US adapt successful techniques from Costa Rica to improve their own structure of healthcare support? Research suggests mimicking successful policies such as that of Costa Rica, fostering an inclusive environment, and intersectoral collaboration are ways in which the US could improve rather than pouring more money into an already flawed process.

Evidence from 2015 illuminates the effort the United States is making to transition to the Costa Rican model of government-sponsored care in an effort to reduce costs. Sarah E. Rudasill of Wake Forest University exemplifies the urgency of the US to follow this model by studying the Costa Rica economic decisions made to prevent deterioration of care quality, such as the cost-cutting measures and centering the value of healthcare in government in order to. Her research suggests US healthcare spending will only increase, but quality of care will improve if similar measures are enacted. Amongst centering the value of human life, Costa Rica promotes the concept of Crenshaw’s Intersectionality in their systems, such a long history of uplifting female doctors. Alternatively, US healthcare is notorious for gender discrimination in the workplace. For example, although women make up 76% of healthcare positions (Hennein, Gorman, Chung, & Lowe 2023), women doctors in the US experience slower advancement, less favorable evaluations, and underrepresentation in leadership positions among so much more due to decades of implicit bias and gender inequalities (Newman, Templeton, & Chin 2020). According to Lilly Edgerton of Consejos Superior Universitario Centroamericano, Costa Rica alternatively has an excellent history of the role of women doctors in the development of Costa Rican medicine, including key chronological periods, significant events, and profiles of leading women physicians. Encouraging more women in STEM and improving the workplace experience for many women in the field is a small change but is a great step in the right direction to improve US health equity for women and women of color (Edgerton 2002). Finally, intersectoral collaboration creates hope by promoting health equity and focusing on the social determinants of health in the Americas. Employing a multi-dimensional analysis model, the Health Equity Network of the Americas (HENA) “considers the imbalanced interaction between humankind and natural systems to promote health, well-being, and equity and to attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) developed in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (Castro, Sáenz, Avellaneda, Cáceres, Galvão, Mas, Ritterbusch & Urbina Fuentes 2021). HENA’s theoretical framework employs Intersectionality Theory, considers the social determinants of health, and illustrates a view of equality in practice. The organization directly identifies specific cases that contribute to health equity or that require action by studying services that provide public health actions, such as in Costa Rica and Cuba. For example, learning about successful experiences and their impact on public health greatly contributes to the development of strategies and programs, both to improve care practices and health workers’ decisions about human rights. Among improving comprehensive maternal and child care, supporting the health of indigenous and migrant communities, analyzing violations of human rights, and the right to health of historically marginalized populations, researchers also examine the COVID-19 pandemic as a case study to analyze and improve social, political, environmental, and economic impacts. What both this organization and the success of Costa Rica serve to demonstrate is the value of putting healthcare at the forefront of governmental decisions as well as confronting experiences both successful or services that failed in order to learn from mistakes and increase health equity.

Conclusion

We now understand the success of Costa Rica’s institutions is due to their priority of serving people not according to nationality, but by health needs” (PAHO 2020). This is something the U.S. could incorporate not only into their treatment facilities but almost all of their policies and government structure. If they truly respect and protect the rights of all regardless of differences, it is integral that they make changes to support the needs of those who have been marginalized since this nation’s establishment.

Although there is a strong case for using Costa Rica as an example to improve US services, limitations prevalent in this essay provide a few challenges. There is a severe lack of accessible and recent statistical data on the status of public health in Latin America. I struggled immensely to find up-to-date statistics to create a strong foundation for this paper. More funding for current and more easily accessible data would greatly improve the influence of Costa Rica to demonstrate their success compared to other models with lower-quality care. Further, many of the sources are in Spanish, so if a researcher is not well versed in Spanish they may be confronted with a great challenge. Rather than suggesting translation of these sources where much information could be lost or misinterpreted, I encourage more language conversion programs or hiring employees with backgrounds that support understanding different languages which could be used to widen the scope of places the US could learn from.

This essay serves to present the power of listening and learning from one another. The US has always been a privatized and individualist entity since the colonial period, as evidenced by the work of Luhui Whitebear and Sarah Hoagland among so much more; even by the guest lectures of Carmela Roybal or Arisleyda Diloné. Maria Lugones, Quijones, Crenshaw, and other foundational scholars advocate for elevated concentration, attention, and advocacy for voices that have been marginalized for all of history, even today in a post-colonial society. There are many benefits from collaboration and acknowledging your successes and failures for growth, which the U.S. could take a lot from.

Bibliography

Abrams, M. K., & Tikkanen, R. (2020, January 30). U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2019: Higher spending, worse outcomes?. U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2019 | Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019?gclid=Cj0KCQjw7pKFBhDUARIsAFUoMDbVZBN2PrzOlYBZvEe8qGs1PvCiAAxHemHZb_FjjCnAbSdQ0LSPChYaAmLYEALw_wcB

Campbell Barr E, Marmot M (2020). Leadership, social determinants of health and health equity: the case of Costa Rica. (https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/53156).

Castro, A., Sáenz, R., Avellaneda, X., Cáceres, C., Galvão, L., Mas, P., Ritterbusch, A. E., & Urbina Fuentes, M. (2021). The Health Equity Network of the Americas: inclusion, commitment, and action. Pan American Journal of Public Health, 45, 1–7. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.26633/RPSP.2021.79

Chinn, J. J., Martin, I. K., & Redmond, N. (2021). Health Equity Among Black Women in the United States. Journal of women’s health (2002), 30(2), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8868

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Policies.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989, no. 1 (1989): 139-167.

Diloné, Arisleyda. In Class Guest Lecture. Pomona College, Carnegie 110. Tuesday, April 9th, 2024

Edgerton, L. 1., & Edgerton, L. 1. (2002). Las médicas en la historia de la Salud de Costa Rica (1. edición.). San José, C.R.: AMECORI.

Health at a glance 2023: Highlights for Costa Rica. OECD. (2023). https://www.oecd.org/costarica/health-at-a-glance-Costa-Rica-EN.pdf

Health at a glance 2023: Highlights for the United States. OECD. (2023). https://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/health-at-a-glance-United-States-EN.pdf

Hennein, R., Gorman, H., Chung, V., & Lowe, S. R. (2023). Gender discrimination among women healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a mixed methods study. PloS one, 18(2), e0281367. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281367

Hoagland, Sarah Lucia (2020). Aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge. Critical Philosophy of Race 8 (1-2):48-60.

Institute of Medicine. 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10260.

Lugones, M. (2016). The Coloniality of Gender. In: Harcourt, W. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Development. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-38273-3_2

McKoy, J. (2023, October 31). Racism, sexism, and the crisis of Black Women’s Health. Boston University. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2023/racism-sexism-and-the-crisis-of-black-womens-health/#:~:text=Black%20women%20are%20more%20likely,or%20have%20uncontrolled%20blood%20pressure

Miller, L. J., & Lu, W. (2018, September 19). U.S. near Bottom, Hong Kong and Singapore at top of health havens. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-09-19/u-s-near-bottom-of-health-index-hong-kong-and-singapore-at-top

Mills, C.W. (1959) The Sociological Imagination. Oxford University Press, New York.

Mujica, O. J., Sanhueza, A., Carvajal-Velez, L., Vidaletti, L. P., Costa, J. C., Barros, A. J. D., & Victora, C. G. (2023). Recent trends in maternal and child health inequalities in Latin America and the Caribbean: analysis of repeated national surveys. International Journal for Equity in Health, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1186/s12939-023-01932-4

Newman, C., Templeton, K., & Chin, E. L. (2020). Inequity and Women Physicians: Time to Change Millennia of Societal Beliefs. The Permanente journal, 24, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/20.024

Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. (2021, December 3). Afro-descendants in Latin American countries live in starkly unequal conditions that impact health and well-being, PAHO study shows. PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization. https://www.paho.org/en/news/3-12-2021-afro-descendants-latin-american-countries-live-starkly-unequal-conditions-impact

Pesec, M., Ratcliffe, H. L., Karlage, A., Hirschhorn, L. R., Gawande, A., & Bitton, A. (2017). Primary health care that works: The Costa Rican experience. Health Affairs, 36(3), 531–538. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1319

Prado A, Rodríguez P, Salas A, 2019. Innovation in the Public Sector: The Costa Rican Primary Healthcare Model. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 4, Issue 2.

Rosero-Bixby, L., & Dow, W. H. (2016). Exploring why Costa Rica outperforms the United States in life expectancy: A tale of two inequality gradients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(5), 1130-1137.

Rosero-Bixby L. (2008). The exceptionally high life expectancy of Costa Rican nonagenarians. Demography, 45(3), 673–691. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0011

Roybal, Carmela. In Class Guest Lecture. Pomona College, Carnegie 110. – Tuesday, February 27th, 2024

Rudasill, S. E. (2015). “Comparing Health Systems and Challenges in Costa Rica and the United States.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 7(02). Retrieved from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=979

Santa Cruz Feminist of Color Collective (2014), Building on “the Edge of Each Other’s Battles”: A Feminist of Color Multidimensional Lens. Hypatia, 29: 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12062

Yearby, R., Clark, B., & Figueroa, J. F. (2022). Structural racism in historical and modern US health care policy. Health Affairs, 41(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01466