5 Reproductive Injustice in Palestine — A Product of Coloniality

Sydney McGonigal

Introduction

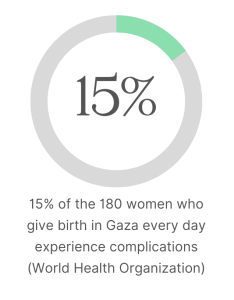

Of the more than 180 women who give birth every day in Gaza as of November 3, 2023, the World Health Organization reports that fifteen percent of them are “likely to experience pregnancy or birth-related complications and need additional medical care” (WHO 2023). Such conditions are clear infringements on reproductive rights and shine a light on the reproductive violations experienced by Palestinians because of Israel’s occupation and genocide of Palestine.

Reproductive justice has been a major topic in the United States in recent history, especially given the overturn of Roe v. Wade in 2022 with the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that removed the nationwide right to abortion. I, like many, was outraged by this decision, and during and after the decision, I dedicated myself to learning more about reproductive rights and reproductive justice in the United States and, later, around the world. It was through this research that I learned about the racist and classist roots and implications of reproductive healthcare and the impact the lack of reproductive justice has beyond the white, able-bodied, cis-gendered perspective.

The current colonial genocide of Palestinians by Israel draws direct parallels to reproductive injustice under and after colonialism, with the treatment of Palestinian mothers comparable to the way that people of color in the U.S., especially Black and Indigenous people, are disproportionately affected by reproductive injustice. Moreover, with the attack on reproductive healthcare in the U.S. after Roe, it has become obvious that men wish to control and regulate women’s bodies, just as the white patriarchy wishes to control the bodies of people of color. After all, reproductive injustice is fueled by “structural racism and cissexism [which] cannot be separated from the dominant framework of binary gender” (Yam and Fixmer-Oraiz 2023, 363). Thus the connection between the cisheteropatriarchy that enforces abortion bans and racist structures derrived from colonialism become ever more apparent. Moreover, “cis white women of means are encouraged toward marriage and motherhood [while] the reproductive and familial desires of people of color, queer people, immigrants, people with disabilities, and poor people are discouraged, even violently denied” (Yam and Fixmer-Oraiz 2023, 363). This divide in who is and who isn’t encouraged to reproduce emphasizes the argument that reproductive injustice unfairly and largely targets minorities and props up the ruling, dominant class of rich white people, much like colonial times did. Moreover, the attack on bodily autonomy brought on by Dobbs has opened the door to more attempts to “criminalize and otherwise demonize trans and queer bodily autonomy across the US” (LeMaster 2023, 351)

In this paper, I explore and analyze what reproductive rights and reproductive justice look like in Palestine, both before and after the events of October 7, 2023. I will examine them in relation to reproductive rights in Israel and other indigenous and marginalized groups, primarily in the United States, to find similarities between the stances and regulations on reproductive health in the United States and Israel and the discriminatory policies that marginalized groups in these countries are subjected to. Moreover, I examine the Israeli government’s treatment of Palestinians through the lens of coloniality, specifically the Coloniality of Power, Knowledge, and Gender, and through the lens of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s concept of the “subaltern” to understand the infringement of Palestinian reproductive rights as it relates to global and transnational theories.

Theories of Coloniality

At its core, the fight for reproductive rights is the fight for self-sovereignty and bodily autonomy — the right to choose whether or not to have children and the right to raise them in a safe and healthy environment (National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda) — and a fight control by another entity, which contains many aspects of the fight against colonialism and coloniality. In many ways, such struggle is similar to the fight against colonialism and coloniality, as they aim to liberate colonized peoples and free them from the thinking and systems of colonizers and colonialists. As such, the battle for reproductive justice, especially in the Global South, can be understood through many of the frameworks through which the deconstruction of coloniality is understood. This is particularly relevant when it comes to Palestine, as it is simultaneously engaged in a fight against colonialism and a consequential struggle for reproductive rights.

The Coloniality of Knowledge is the idea coined by Peruvian sociologist and humanist thinker Anibal Quijano, which states that Western institutions hold Western ideas about the world above all else and ignore knowledge from indigenous and colonized populations. Sarah Hoagland expands on Quijano’s analysis and describes five aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge, the fifth of which is that “others [non-Westerners] have been reorganized economically, spiritually, linguistically, [and] socially through the praxis of colonization.” (Hoagland 2020, p. 57). In addition to that description, she states that those people are then considered inferior because of the “racialized codification of differences” (Idem). The formerly colonized nations may have defeated their colonizers, but they still have to fight against and grapple with colonization and coloniality, as it is deeply embedded in their structures. Because of this, the prejudice and racism of the colonizers have continued, both through colorism within nations and in outside perceptions of so-called “Third World countries” that perpetuate the narrative that these countries are lesser and uncivilized, the very same narratives that were used to justify colonialism in the first place. Today, that outside perspective has grown to encompass all countries in the Global South, even those never colonized, as the West and its thinking have grown exponentially in power, and all those who do not fit into the Western standards of progress and cultural and societal structure are disregarded. Thus, places like Palestine and the Middle East as a whole have been devalued, despite the Islamic World once being the center of innovation and progress, their impact on the world is lost to time as the Coloniality of Knowledge takes over (Overbye 2001).

Similarly, Quijano’s concept of the Coloniality of Power presents the idea that the power dynamics of today are rooted in colonial structures and continuing coloniality. He argues that a Eurocentric understanding of the world rose up during colonialism and has never left, with nation-state formation rooted in borders previously decided by Western Europe through the formation of colonies or Western European ideas about where borders should be drawn (Quijano 2000). The formation of Israel is a prime example of Europe deciding the placement of borders and settlements, as the British government “protected Jewish immigration, encouraged Jewish settlement, subsidised Jewish defence and protected […] Palestine’s minority Jewish community […] from the native population” (Glass 2001). Moreover, the Coloniality of Power also includes the “codification of the differences between conquerors and conquered in the idea of ‘race’” by claiming race as a “biological structure that places some in a natural state of inferiority to the others” (Quijano 2000, 533). Through this reasoning, the U.S. and countries in Western Europe devalue the countries with a majority of people of color, declaring themselves superior and giving themselves the power to decide what is best for others, particularly those countries they deem inferior.

Another concept that expands on Quijano’s analysis of coloniality is the Coloniality of Gender, adapted from Quijano’s Coloniality of Power by Maria Lugones. The Coloniality of Gender is the idea that in addition to the racial power dynamics created by colonialism, gender — a social construct, just like race — was imposed onto colonized nations, by subjecting colonized people to the values and expectations of the European concept and ideas of gender. The basis of the Coloniality of Gender starts with the European gender hierarchy that places men over women and extends to how it combined with racism and spread to colonized states. When the ideas of gender were brought to colonized locations, the structures were imposed onto the societies, with the inferiority of women being adopted by some colonized groups. But where the distinction between the colonized and the colonizer came into play was in who the colonizers considered to be “real” women. Lugones explains that gender was only applied to white women, with women of color considered “female” but not “women,” purposefully akin to how animals are classified as female rather than women (Lugones 2008). This perspective enables white women to look down upon women of color, especially women who live in the Global South or those who do not follow white understandings or structures of gender, and exclude them from their definitions of womanhood, of femininity, and of feminism.

This perspective also shares similarities with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s concept of the “subaltern,” or those otherized in an already otherized society by the dominant Eurocentric society and thus are invisible in mainstream understandings of the world and even of the otherized world. Spivak’s main argument is that what makes these groups of people “subaltern” is that they do not have a voice in the greater society — they are spoken for by those in power and often misrepresented and, to be heard, they must alter aspects of their story or themselves in order to be digestible to their oppressors as the language used to describe their lives is untranslatable in academia (Spivak 1988). She later refers to this concept as “strategic essentialism,” explaining that marginalized and subaltern groups are forced to temporarily essentialize their identity to be heard and make progress politically, despite the risk of reinforcing existing power structures in doing so.

Palestine, Reproductive Rights, and Maternal Health

Even before Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, and the war and genocide that followed, Palestinian women did not have access to the same rights as Israeli women. One such right that Palestinian women were denied was access to abortion. A December 2014 study found that in the West Bank, abortion is prohibited “by any means unless necessary to save the pregnant woman’s life,” and, although the laws that applied to the West Bank were said to have applied to Gaza as well, female interviewees in the study expressed that they “felt that there is virtually no access to abortion services in Gaza” (Shahawy 2019, 52). But while Gazans felt that they had no access to abortion, Palestinians in East Jerusalem and the West Bank were able to receive one — so long as two specialist physicians backed up the need for one and they received written approval from their husbands or guardians (Idem).

In her interviews, Shahawy was told by Gazan women that the law in Gaza only allowed abortion in cases where pregnancy directly put the woman’s life in danger and did not make any exceptions, even for unmarried women who had gotten pregnant or in instances of rape (Shahawy 2019, 49). And while Palestinians living in East Jerusalem have access to Israeli hospitals and are covered by insurance — although they have a “‘permanent residency’ status” that gives them fewer rights than Israelis who have citizenship status (Idem) — Palestinians from the West Bank who are able to cross over into East Jerusalem have to pay a hefty fee to pay for the service. This is especially a problem when they need an abortion that would not be allowed in the West Bank and have to travel into East Jerusalem — or go to an expensive private Palestinian clinic — in order to receive the procedure (Idem). For women who can’t pay that fee, they are forced to turn to “self-induced termination” and some women in the study recounted their own or friend’s experiences with at-home abortions: “One woman said, ‘I know some who aborted at home: jumped, carried heavy things, or let her kids jump on her. And then she aborted and went to the hospital for cleaning’” (Idem). Pregnancy and childbirth were also difficult for pregnant women in Gaza before October 7, largely because hospitals “often lacked adequate equiptment” and “more than half of pregnant women were anemic” (Loveluck et al. 2024).

On the other side of the border, however, Israelis in Jerusalem and the rest of Israel have much easier access to abortion. Like the Palestinian women who reside in East Jerusalem, Israeli women can go to abortion clinics and hospitals and have access to the Israeli healthcare and insurance system, without the limitations that Palestinians in East Jerusalem are subjected to. In fact, in 2019, Israel was “among the world’s most liberal countries when it [came] to abortion” (Shahawy 2019, 53). In response to the 2022 overturn of Roe vs. Wade in the United States — which Israeli Health Minister Nitzan Horowitz proclaimed “turned back the clock for women’s rights” — Israel loosened its abortion laws even further, with the new rules “grant[ing] women access to abortion pills through the country’s universal health system and remov[ing] a longstanding requirement that women appear physically before a special committee before they are permitted to terminate a pregnancy” (Rose 2022). In fact, the government approved “termination committees […] composed of two doctors and a social worker, approve 98 percent of abortion requests” in Israel (Shahawy 2019, 53). In contrast, more than 10,000 Palestinian women received illegal abortions from the PFPPA, a Jerusalem-based nonprofit organization, in 2014 because they were not able to get them legally (Shahawy 2019, 50). The drastic difference in Israel’s policies on abortion in Israel and in Palestine exposes Israel’s hypocrisy, revealing the discriminatory and colonial grounds for the difference in the policies.

Some Palestinian women didn’t mind the abortion bans, as to them, having a baby was a “form of resistance and annoyance to [their] occupier” (Shahawy 2019, 54). Moreover, many women were distrustful of abortions performed by or allowed by Israel, as they worried that Israeli hospitals would perform abortions to “stop Palestinian women from procreating” (Idem). This “pro-natalist policy” was also supported by the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Palestinian Authority. In this perspective, motherhood was a political statement that could empower Palestinian women but still wasn’t challenging the standing social order imposed by Israel (Idem).

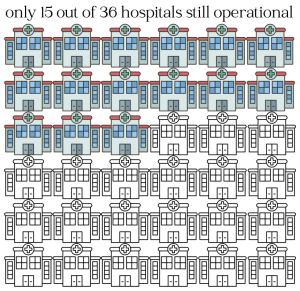

After the Hamas attack on October 7, however, the circumstances in Gaza changed drastically. With the ongoing genocide in Gaza, hospitals have been heavily impacted, as they have to care for the estimated 60,000 injured Gazans (as of January 18, 2024), and are also collapsing due to Israeli bombings (Lederer 2024). And in addition to health facilities being severely damaged or outright non-functioning, the displacement of Gazans and the lack of water, electricity, food, and medicine have had immense impacts on maternal, newborn, and child health services. The World Health Organization expects maternal deaths to increase given that women are unable to get the medical care they need (WHO 2023). Moreover, “[r]ising food scarcity and malnutrition” that Gazans are experiencing can cause “potentially life-threatening complications during childbirth and lead to low birth weight, wasting, failure to thrive and developmental delays” (Loveluck et al. 2024). In addition to the physical contributions to pregnancy complications, the psychological toll has played a great impact as well, with stress-induced miscarriages, stillbirths, and premature births becoming increasingly more common (WHO 2023).

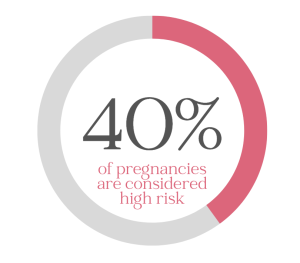

The reality of the lives of pregnant people in Palestine doesn’t stop there, as, according to Ammal Awadallah, the Executive Director of the Palestinian Family Planning and Protection Association, pregnant women are only admitted to a health center or hospital when they are fully dilated and are discharged afterward within hours because of the “lack of capacity and resources in hospitals” (Abirafeh 2023). The International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) added that women denied from hospitals are forced to give birth in cars or even in places with high risk of infection such as overcrowded and unsanitary shelters. What’s more, the IPPF states that some pregnant people “have no choice but to undergo a c-section without anesthesia due to the dire lack of medical supplies” (Abirafeh 2023). The conditions don’t improve after giving birth either, as the lack of access to food and water has made many women have trouble producing the milk needed to breastfeed their babies (Idem). And unfortunately, not all mothers make it through the birth — with “an estimated 40% of current pregnancies […] considered high-risk [and] only 15 out of 36 hospitals […] still operational and […] filled at 250% of their capacity” (CARE 2024). In fact, UNICEF Spokeswoman Tess Ingram said she “met a nurse at Gaza’s Emirati maternity hospital who had helped with postmortem caesarians on six dead women” (Loveluck et al. 2024).

have trouble producing the milk needed to breastfeed their babies (Idem). And unfortunately, not all mothers make it through the birth — with “an estimated 40% of current pregnancies […] considered high-risk [and] only 15 out of 36 hospitals […] still operational and […] filled at 250% of their capacity” (CARE 2024). In fact, UNICEF Spokeswoman Tess Ingram said she “met a nurse at Gaza’s Emirati maternity hospital who had helped with postmortem caesarians on six dead women” (Loveluck et al. 2024).

Reproductive healthcare goes beyond pregnancy and birth, and women and girls in Gaza have been affected by Israel’s attacks in other ways as well. Lacking pads, tampons, or other safe alternatives, they use scrap fabric or period-delaying pills, the latter of which could have dangerous side effects (Abirafeh 2023). Contraception is also hard to come by since the bombardments began, with some women sharing birth control pills, women with IUDs facing bleeding and infections because of the unsanitary conditions they are forced to live in, and condoms being all but unavailable (Idem). The combination of these has resulted in unintended pregnancies and the latter of the three results in the transmission of HIV and other STIs. With the dwindling of the methods of preventing pregnancies and the increase in infections and complications, the chances that a woman gets pregnant and either gives birth on her own without anesthesia or has a complication in the pregnancy and loses the baby rise tremendously (Idem).

What’s more, an article from December 21, 2023, stated that pregnant Palestinian women in labor are blocked at checkpoints, stopping them from reaching medical facilities (Naber 2023). Moreover, while Palestinians’ reproduction is blocked, the article claims that Jewish Israelis are pressured to reproduce — largely through societal expectations that people marry and have multiple children and “Holocaust generational trauma” that leads Israelis to feel it is their duty to reproduce in order to increase the number of Jewish people (Kubes) — giving even more credence to the fact that Israel wants to increase the Israeli population and decrease the Palestinian one (Idem). These forms of reproductive injustice or violations resemble and are intrinsically tied to historical reproductive injustices in the U.S. and other settler-colonizers, including, and perhaps most relevantly, the forced sterilization of Indigenous women in the U.S. (Liddel et al. 2022). Similarly, the IPPF references the acknowledgment in recent decades of the “demographic threat” and “security threat” that higher Palestinian fertility rates pose to Israel, emphasizing how the Israeli government feels the need to “implement policies restricting population growth” (Abirafeh 2023). And by stripping reproductive rights and freedoms from Palestinians, the Israeli government has done just that.

The Coloniality of Reproductive Rights

Although the height of colonialism has long since passed, coloniality and colonialism itself continue to persist. Israel is one such case — a settler colonizer state that has pushed many of the native Palestinian people off of their land and into designated areas (Gaza Strip and the West Bank) and whose government has severely restricted the native population’s rights, much like the actions of the colonizers who settled in North America. Quijano’s theory of the Coloniality of Power exposes the colonial circumstances that created Israel and allows for Israel’s colonial practices. Not only is the immigration of European Jewish people to Palestine a prime example of settler colonization, but the conversation surrounding the Israel–Palestine “conflict” is also seeped in coloniality and colonial language. The Coloniality of Power tells us that the social construct of race is used to create differences between the conquerors and the conquered — the colonizers and the colonized — and use those differences to justify hierarchies of power that put the conquered into positions of inferiority. It is this mindset that supports the occupation of Palestine, as Palestinians, who are primarily people of color, are considered inferior and uncivilized, while Israelis are lauded as civilized and superior. In fact, the Israeli government is often called “the only democracy in the Middle East,” likening it to the governments of the U.S., England, and other countries in the West, thus prompting Westerners to see Israel as more civilized and a more “valid” government than Palestine and other countries in the Middle East.

This view of the Israeli government can also be explained through the Coloniality of Knowledge, as it causes Westerners, and particularly the U.S. government, to put more stock in what official Israeli claims say about Palestine rather than Palestinian citizens and even journalists, seeing Israeli claims as more correct and precise, Therefore, when the Israeli government villainizes Palestinians and claims the land for Israel — thus creating justification for its settler colonization — they are able to convince Westerners to believe them because Westerners are told that Israel is “better” and more “civilized” like Western nations, unlike Palestine and other countries in the Middle East.

All of these tactics have allowed Israel to continue with its colonizing practices without pushback from people in Western countries — until more recently in the wake of the Israeli government’s increased attacks on Palestinians. Because of this, the Israeli government has been able to create a hierarchy that places it at the top and Palestinians at the bottom, subsequently putting the Israeli government in a position to limit the rights of Palestinians, including reproductive rights. Additionally, many are calling the increased attacks acts of genocide as they specifically target Palestinians, seemingly with the intent of driving them out of Palestine or outright killing them. But genocide is not restricted to overtly violent actions, which Patrick Wolfe emphasized when he coined the term “structural genocide,” which describes the aspect of settler colonization that uses policies and structures to eliminate the native population (Wolfe 2006). These structures and policies are ones directed at natives and aim to eliminate the native population, either by killing them, imprisoning them, or stopping their reproduction (Idem). Thus, both the restrictive abortion laws in Gaza and the West Bank and the inhumane conditions and lack of maternal and infant healthcare that lead to maternal and infant deaths in Gaza are examples of structural genocide that add another layer to the current, “traditional” genocide in Gaza. It is through the Coloniality of Power and the Coloniality of Knowledge that we can understand why this genocide is happening, as it reveals the systems and structures that enabled the colonial occupation of Palestine and the colonial practices that Israel continues to engage in.

The Coloniality of Gender, like the Coloniality of Knowledge, is an extension of the Coloniality of Power. Thus the way women in Palestine are viewed by the rest of the world — and in particular, how white and Western women view them — reflects how the rest of the world views Palestinians. In the United States, for example, there is a strong reproductive rights movement that stands against the injustices Palestinian women are facing. But because Palestinian women aren’t considered “women” in the way that white women are — because of the white, colonial ideas of gender that are imposed on the rest of the world — Western and white feminists are not speaking out against the infringement of Palestinians’s reproductive rights, despite that being the very thing they stand against. In fact, some reproductive rights activists in the U.S. have called out reproductive rights organizations for ignoring Palestinian women, and they have also directed their outrage at current U.S. president Joe Biden, who used reproductive rights as part of his reelection campaign but simultaneously backs the Israeli government in their fight against Hamas, which has resulted in the increased and deadly attacks in Gaza (Corbett 2024). According to Corbett and the reproductive rights activists who have spoken out, the reproductive rights movement is fractured between those who support Palestine and are wary about supporting Biden and those who support Biden despite his backing of the Israeli government (Idem). The large amount who fall into the latter category reveals how many white, liberal feminists in the United States care about issues such as reproductive justice when it applies to their own country — and, more specifically when it applies to white people — but not when it applies to people in other countries — and specifically people of color. This hypocrisy aligns precisely with Lugones’ theory of the Coloniality of Gender, as it highlights how Western women don’t see Palestinian women as worthy of the same rights they want for themselves seeing as they don’t consider Palestinian women to be women in the same way they see themselves as women, stemming from the colonial element of gender. This concept also applies to the abortion laws that restrict Palestinian women’s access to abortion. Because Israeli women are not subjected to the same laws, it becomes clear that the Israeli government does not see Palestinian women as deserving of the same right to abortion that Israeli women have. This difference in its stance on abortion for Israeli women and Palestinian women stems from the hierarchy established by colonialism combined with the European idea of gender and of womanhood that forces gendered norms onto colonized people whilst excluding colonized women from womanhood.

When explaining the Coloniality of Knowledge, Hoagland identifies a key aspect that heavily relates to Spivak’s theory of the “subaltern.” In “Aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge,” Hoagland writes that “the only discourse for articulating third world women’s lives is a norming and normative anglo-european one” (Hoagland 2020, 50). In order for women in the “third world” to be heard by women in the “first world,” they must speak in the language of the first world. Similarly, the “subaltern” represents those who are invisible, the ones who have no voice in the dominant discourse. Spivak comes to the conclusion that the subaltern cannot speak, and if they are to speak, it is not in their language. Thus, anything that the subaltern says must be done through Western systems and languages (Spivak 1988). In the case of Palestine and Gaza, Gazans are silenced in the media, and, in order to make their voice heard, they must use Western vehicles or communication — the English language and social media — and appeal to the sympathies of the West to receive help. Moreover, the combination of these two exemplifies how they do not have a voice unless they chance themselves and comply with the dominant structures and language. After all, it is colonialism and coloniality — and the resulting hierarchies of power and knowledge — that create the circumstances that silence the subaltern, as the thing that otherizes them in the first place is something that does not fit into Western ideals or understandings of the world.

The theory of the subaltern also relates to the hierarchical structure of power that devalues non-Western lives and even refuses to see them as humans, as seen through the lack of concern that Western governments seem to have for the thousands of Palestinians who have died. A clear example of this is Biden’s response to the killing of the World Central Kitchen workers, specifically in contrast to the lack of a reaction to the thousands of Palestinian deaths, as the World Central Kitchen deaths included a dual US-Canandan citizen, one person from Australian, one from Poland, three from the United Kingdom, and one Palestinian (Salman et al. 2024). In response to the World Central Kitchen deaths, Biden, along with many others, expressed his “outrage” at the World Central Kitchen employees being killed, with his response including “some of the most fiery and blunt language from the president since the start of the Israel-Hamas war in October” (Lee 2024). What’s more, Biden added that the U.S. government would continue to support the Israeli government in its war with Hamas despite the more than 34,500 Palestinians who have been killed since October 7 (Lee 2024; Mccready et al. 2024). Biden’s reaction to Westerners being killed in Israel differs drastically from his reaction to the thousands of Palestinians killed, highlighting how the U.S. government and other Westerners place less value on Palestinian lives compared to Western lives.

This is also noticeable in news headlines about Palestine and Israel. Palestinian deaths are reported in the passive voice, often with no mention of who killed them, whereas reports of Israeli deaths attribute the killings to Hamas using “[h]ighly emotive terms,” with terms such as “slaughter,” “massacre,” and “horrific” used “almost exclusively for Israelis killed by Hamas” (Johnson and Ali, 2024). Moreover, news reports rarely mention the Palestinian children killed by Israel, with Palestinian children referred to by other terms such as people “under the age of 18” (Idem). This refusal to name what killed Palestinians — as if they just ended up dead — and the trend of calling children other terms to make their deaths seem less tragic at a glance dehumanized Palestinians, turning them into figures in reports rather than real people. The dehumanization of minority groups makes them less accepted in a = society riddled with coloniality and remnants of colonialization, leaving them to be cast aside as subalterns.

Conclusion

Reproductive rights have the potential to unite feminists and women around the world in a fight against patriarchal structures; however, many women in the West ignore the colonial implications of being denied reproductive rights, and thus Native Americans, Palestinians, and people of color around the world are excluded from the dominant reproductive rights movements. But what we can learn from Palestine is that the conditions that created reproductive injustice do not exist in a vacuum, but instead were produced in a system of coloniality and settler-colonialism that aims to control — and eventually eliminate — the native populations for the benefit of the colonizer.

In the U.S. and around the world, female sexuality and reproduction are heavily restricted in order to control populations, women’s bodies and choices, and monitor native populations. Because of the connections between colonialism and cis-heteropatriarchy, infringements of reproductive rights are all connected, stemming from the same structures of power that place white (cishet) men at the top. Thus, the conditions that Palestinian women face, both before and after October 7, can tell us a lot about the fight for reproductive rights, the pushback from conservatives, and the circumstances that create the need for the debate in the first place. From the overturn of Roe v. Wade and abortion bans in the U.S. — including one in Arizona that reinstated a law passed during the Civil War before Arizona was a state (Snow and Lee 2024) — to the violations of Palestinian reproduction and maternal health, reproductive justice is a crucial aspect of transnational feminist movements today.

But while the U.S. seems to be making progress toward regaining abortion rights in some states that added bans — the Arizona ban was repealed by Governor Katie Hobbs on May 2, 2024 (Snow and Lee 2024) — no such progress is being made for Palestinians and many indigenous people and other marginalized groups in the U.S. who have historically (and currently) been subject to worse reproductive rights violations. On Native American reservations, indigenous women experience high rates of sterilization, as well as “high rates of endometriosis and [an] inability to pay for fertility treatments,” the latter two being “less frequently explored through the lens of reproductive justice,” even compared to the former, which is ignored by many mainstream reproductive rights conversations (Liddell et al. 2022, 397). Moreover, these issues are even less explored for women who are not part of federally recognized tribes and thus do not receive healthcare from the Indian Health Service or any other centralized healthcare system (Idem). “[E]xisting social hierarchies” are further reproduced by reproductive health policies and limitations that are “surveilling and curtailing the reproduction of certain marginalized groups,” making women’s reproduction “rooted in racialized, gendered, and classes notions of worthy and unworthy mothers” (Idem). As a result of this, between 2008  and 2016, Indigenous women “have seen a rapid decrease in fertility” (Liddell et al. 2022, 407). Thus, just as the conditions faced by Palestinian women arise from colonial hierarchies, the attitude that the U.S. government has toward Indigenous reproduction — as well as the reproduction of groups marginalized through race, gender, or class — stems from the colonial and racist history and current structures of the United States. These conditions that Native American women face are another key example of Wolfe’s concept of structural genocide, with the reproductive laws imposed on Indigenous people working through structures to control the native population. Furthermore, the split between reproductive justice for women who make up the majority population and those from minority groups amplifies the role of coloniality in understandings of gender and womanhood, as these Indigenous groups are excluded from reproductive justice movements, just as Palestinians are.

and 2016, Indigenous women “have seen a rapid decrease in fertility” (Liddell et al. 2022, 407). Thus, just as the conditions faced by Palestinian women arise from colonial hierarchies, the attitude that the U.S. government has toward Indigenous reproduction — as well as the reproduction of groups marginalized through race, gender, or class — stems from the colonial and racist history and current structures of the United States. These conditions that Native American women face are another key example of Wolfe’s concept of structural genocide, with the reproductive laws imposed on Indigenous people working through structures to control the native population. Furthermore, the split between reproductive justice for women who make up the majority population and those from minority groups amplifies the role of coloniality in understandings of gender and womanhood, as these Indigenous groups are excluded from reproductive justice movements, just as Palestinians are.

By imposing colonialism and taking away reproductive rights, the U.S. government and other colonial powers also erase Indigenous culture and knowledge: “Indigenous peoples have utilized the knowledge of medicinal plants throughout every stage of reproductive health care – including abortion [and] menstruation, contraception, pregnancy, the birthing process, after birth, breast feeding, uterine health, and menopause” for centuries” (PPGNY 2023). This erasure aligns with Quijano’s Coloniality of Knowledge, and specifically the coloniality of medicine, showing just one more way that colonialism harms Indigenous people by dismissing their knowledge, culture, and existence under the assumption that colonial knowledge is superior.

Disabled people in the United States are similarly targeted by violations of their reproductive rights, as, just like Indigenous women, disabled people are subjected to “compulsory sterilization” (Hassan et al. 2023, 347). This compulsory sterilization is rooted in the eugenics movement, which “imposes a hierarchy on who can reproduce by placing value on bodies” (Idem). This hierarchal structure is the very same one that places Israeli lives over Palestinian lives, white lives over Black, Brown, and Indigenous lives, and men’s lives over women’s lives — the colonial structure that places the conqueror over the conquered, with the subaltern at the very bottom.

Dominant reproductive rights movements are largely concerned with the right to abortion, but reproductive rights have a much broader scope, particularly when concerning marginalized groups like Indigenous people and Palestinians who lack access to maternal healthcare, menstrual products and care, and resources for pregnancy and birth. When we look beyond the dominant narrative and understanding of reproductive justice, we learn so much more about the world and the intricacies of reproductive rights, coloniality, and hierarchies of race and power.

References

AbiRafeh, Lina. “No Freedom without Reproductive Freedom for Palestinian Women.” IPPF, 8 Dec. 2023, www.ippf.org/featured-perspective/no-freedom-without-reproductive-freedom-palestinian-women.

CARE. “Gaza 100 Days: Urgent Focus on Maternal and Reproductive Health Needed.” CARE International, 12 Jan. 2024, www.care-international.org/news/gaza-100-days-urgent-focus-maternal-and-reproductive-health-needed-4.

Corbett, Jessica. “Biden Runs on Reproductive Rights as Movement Fractures over Gaza.” Common Dreams, 19 Feb. 2024, www.commondreams.org/news/biden-abortion.

Glass, Charles. “The Mandate Years: Colonialism and the Creation of Israel.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 31 May 2001, www.theguardian.com/books/2001/may/31/londonreviewofbooks.

Hassan, Asha, et al. “Rebuilding a reproductive future informed by disability and reproductive justice.” Women’s Health Issues, vol. 33, no. 4, 21 Apr. 2023, pp. 345–348, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2023.04.006.

Hoagland, Sarah Lucia. “Aspects of the Coloniality of Knowledge.” Critical Philosophy of Race, vol. 8 no. 1, 2020, p. 48–60. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/747658.

Johnson, Adam, and Othman Ali. “Coverage of Gaza War in the New York Times and Other Major Newspapers Heavily Favored Israel, Analysis Shows.” The Intercept, 10 Jan. 2024, theintercept.com/2024/01/09/newspapers-israel-palestine-bias-new-york-times/.

Kubes, Danielle. “The Truth behind Israel’s Curiously High Fertility Rate.” National Post, Postmedia Network, 26 Feb. 2023, nationalpost.com/opinion/danielle-kubes-the-truth-behind-israels-curiously-high-fertility-rate.

Lederer, Edith M. “UN: Palestinians Are Dying in Hospitals as Estimated 60,000 Wounded Overwhelm Remaining Doctors.” AP News, The Associated Press, 18 Jan. 2024, apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-un-gaza-hospitals-overwhelmed-7c6c549b4bb52f0917957bb7c4143b2d.

Lee, MJ. “Biden Furious over Deaths of World Central Kitchen Workers, but White House Has No Plans to Change Israel Policy | CNN Politics.” CNN, Cable News Network, 3 Apr. 2024, www.cnn.com/2024/04/02/politics/biden-white-house-world-central-kitchen/index.html.

LeMaster, Lore/tta. “After Roe: Teaching and Researching Reproductive Justice.” Women’s Studies in Communication, vol. 46, no. 4, 2 Oct. 2023, pp. 351–353, https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2023.2264134.

Liddell, Jessica L., and Celina M. Doria. “Barriers to achieving reproductive justice for an indigenous Gulf Coast tribe.” Affilia, vol. 37, no. 3, 1 Mar. 2022, pp. 396–413, https://doi.org/10.1177/08861099221083029.

Loveluck, Louisa, et al. “Gaza Infant, Maternal Deaths Spike in War, Doctors and Aid Officials Say.” The Washington Post, 21 Jan. 2024, www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/01/21/gaza-childbirth/.

Lugones, María. 2008. “Coloniality of Gender” Worlds & Knowledges Otherwise, Spring 2008, pp. 1–17.

Mccready, Alastair, et al. “Israel War on Gaza: Live Updates: Today’s Latest from Al Jazeera.” Al Jazeera, Accessed on 4 May 2024, www.aljazeera.com/news/liveblog/2024/5/4/israels-war-on-gaza-live-talks-in-egypt-set-to-steer-wars-direction.

Naber, Nadine. “Reproductive Justice from Turtle Island to Palestine.” Feminist Studies, vol. 49, no. 2–3, 2023, pp. 545–546, https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2023.a915923.

National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda. “Reproductive Justice.” In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda, 2024, blackrj.org/our-causes/reproductive-justice/.

Overbye, Dennis. “How Islam Won, and Lost, the Lead in Science.” The New York Times, 30 Oct. 2001, www.nytimes.com/2001/10/30/science/how-islam-won-and-lost-the-lead-in-science.html.

Planned Parenthood of Greater New York. “Indigenous Health Rights Are Reproductive Justice.” Planned Parenthood, 22 Nov. 2023, www.plannedparenthood.org/planned-parenthood-greater-new-york/blog/indigenous-health-rights-are-reproductive-justice-2.

Quijano, Anibal. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America” Nepantla: Views from South 1(3), 2000, pp. 533–580.

Rose, Emily. “Israel Loosens Abortion Regulations in Response to Roe.” AP News, 27 June 2022, apnews.com/article/abortion-us-supreme-court-politics-health-israel-68e6acadda5b62ff400a7846d0bae147.

Salman, Abeer, et al. “Foreign Nationals among Food Aid Workers Killed in Israeli Attack, as Netanyahu Calls Strike ‘Unintentional.’” CNN, Cable News Network, 2 Apr. 2024, www.cnn.com/2024/04/01/middleeast/world-central-kitchen-killed-gaza-intl-hnk/index.html.

Shahawy, Sarrah. “The Unique Landscape of Abortion Law and Access in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.” Health and Human Rights, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2019, pp. 47–56, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6927376/.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1988 pp. 271–313.

WHO. “Women and Newborns Bearing the Brunt of the Conflict in Gaza, UN Agencies Warn.” World Health Organization, 3 Nov. 2023, www.who.int/news/item/03-11-2023-women-and-newborns-bearing-the-brunt-of-the-conflict-in-gaza-un-agencies-warn.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler colonialism and the elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 8, no. 4, 21 Dec. 2006, pp. 387–409, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

Yam, Shui-yin Sharon, and Natalie Fixmer-Oraiz. “Dobbs, Reproductive Justice, and the Promise of Decolonial and Black Trans Feminisms.” Women’s Studies in Communication, vol. 46, no. 4, 2 Oct. 2023, pp. 362–368, https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2023.2264144.