1 The Return of the Porn Wars: Can There Be Liberation?

Kimberly Hernandez

Professor Esther Hernandez-Medina

Queer Feminist Theories

12/17/2023

The Return of the Porn Wars: Can there be Liberation?

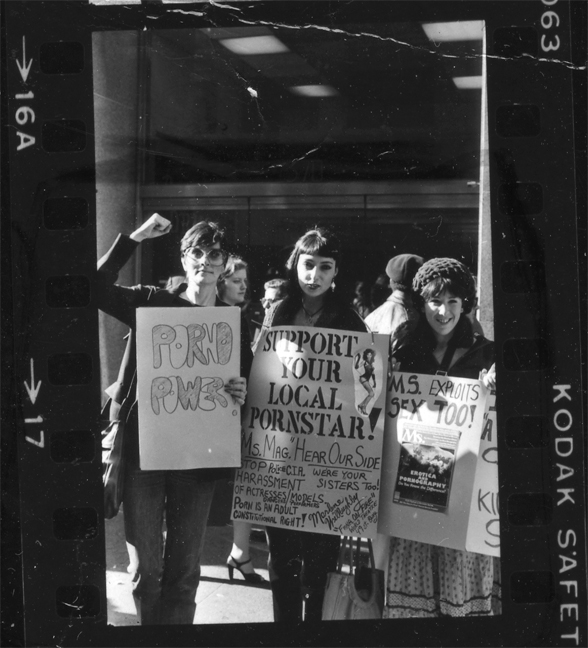

Salucci, Mariavittoria. The History of the Sex Wars, 2021. https://www.nssgclub.com/en/lifestyle/24941/sex-wars-feminism-porn

Can pornography be liberating or is it inherently wrong? In the 1980s feminists fiercely debated this question to decide whether pornography maintained or created sexual oppression. Feminists like Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon argued that pornography was “filmed rape” because of the degrading and abuse women experienced within these videos (Grady 2023). They sustained that in the mainstream porn industry, the subordination of women was not only displayed in videos but it was also practiced in heterosexual relationships. On the other side of this debate, pro-porn feminists argued that the anti-porn position maintained the notion of the “virgin/whore” binary. These feminists believe that outlawing pornography can create a form of sexual oppression because it disregards the fact that women cannot only find agency within it but also enjoy consuming different types of pornography, including even hardcore porn. Pro-porn feminists argue that if pornography can’t be dismantled, then it should be reformed. The reformation of the porn industry has started with feminist pornography. These sites emphasize inclusivity as they include more accurate representations of queer sex, they feature bodies “outside” the Western norm more often and promote the agency of performers.

Fast forward to the present, the debate over porn mirrors that of the 1980s, but with a notable difference, in today’s time, the internet era has made pornography easily accessible to viewers much younger (Grady, 2023). Furthermore, the lack of sexual education in the United States has prompted many young viewers to use pornographic websites as sources of information. Although both sides present valid concerns, a lot of what has been left out of this debate is how women find pleasure and agency through the viewing of pornography. This is the case because for as long as it has been present, the porn industry has revolved around the male experience. Very few analysts have examined the perspective of women who actively view and enjoy pornography. Moving away from the black-and-white perspectives of the anti-porn stance opens the possibility for porn to serve as a tool for sexual liberation.

Literature Review

The Anti-Porn Feminist Stance

In order to understand the porn wars in both the 1980s and the present, it is essential to look into the arguments of both anti-porn feminists and pro-porn feminists. Similarly, to other feminists, Adrienne Rich argues that pornography creates a space where violence and sex are interchangeable, and it allows for the expansion of “the range of behavior considered acceptable from men in heterosexual intercourse…” (Rich p.641). The subordination of women in mainstream porn has become so normalized that men often enact the same practices they view with the women in their lives (Grady 2023). Furthermore, through this industry, women are largely perceived as sexual preys whose sole purpose is to serve as a sexual commodity, so that even lesbian porn is modified to appease the male gaze. Mainstream pornography often emphasizes the subordinate position of women, making them vulnerable to humiliation and physical abuse as it is assumed that women gain pleasure from these acts (Rich p.641).

Lack of Feeling

Another powerful voice within the porn wars was Audre Lorde who argued that the erotic could not be correlated with pornography. In her famous essay, “The Uses of the Erotic” Lorde argued: “But pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling. Pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling” (Lorde p.88). According to Lorde, since the erotic is constantly associated with the superficial like what happens in the bedroom, women have been denied its true power and knowledge. Lorde believes that the use of the erotic goes beyond the bedroom: “And that deep and irreplaceable knowledge of my capacity for joy comes to demand from all of my life that it be lived within the knowledge that such satisfaction is possible, and does not have to be called marriage, nor god, nor an afterlife [emphasis added]” (Lorde p. 89). Therefore, if the erotic is pleasure, satisfaction, and joy within the small things in life, pornography then signifies the contrary, passionless interaction and detachment.

The Other Side: Pro-Porn Feminist Stance

On the contrary pro-porn feminists believe that “the response cannot be to censure what is thought of as pornography, because that, too, becomes another kind of oppression” (Green p.71). For instance, Gayle Rubin, author of “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality,” provides the history of the periods of sex panic. In this essay, Rubin challenges the notion of “sexual correctness” (p.3). During the 1880s, 1950s, and the contemporary era, the West established a long-standing notion that any erotic behavior is unacceptable unless it is done for marriage, reproduction, and love. Rubin introduces the concept of the charmed circle, within this circle only the “good,” “normal,” and “natural,” sex can exist, and the outer circle includes anything “abnormal” like pornography and homosexual sex (Rubin p.13). Although we have come a long way from burning the clitoris with a hot iron as punishment for masturbation as was the case in the 1980s, “[p]romiscuous homosexuality, sadomasochism, fetishism, transsexuality, and cross-generational encounters are still viewed as unmodulated horrors incapable of involving affection, love, free choice, kindness, or transcendence” (Rubin p.15). These “abnormal” modes of sex are an integral part of pornography and until they are seen as sexual delights for some, pornography will continue to be an ethical concern. Whether in pornography or real life:

A democratic morality should judge sexual acts by the way partners treat one another, the level of mutual consideration, the presence or absence of coercion, and the quantity and quality of the pleasures they provide. Whether sex acts are gay or straight, coupled or in groups, naked or in underwear, commercial or free, with or without video, should not be ethical concerns (Rubin p.15).

Instead of focusing on what people might find repulsive within pornography, there should be an acknowledgment of what pornography or “deviant” sex can do to provide liberation. An example of this is Kai Green’s article “Troubling the Waters,” where they examine the contributions by Alycee Lane, founder of Black Lace, a black lesbian erotic magazine. Lane created this space for Black lesbians to explore their desires free of judgment and free of the American imagination. To Lane, “[p]leasure might be brutal, it might be sex or lovemaking” (Green p.71). In contrast to Audre Lorde, Black Lace encourages the readers to enjoy sex however they want even if the sex they enjoy is brutal or it may lack feeling. By shifting away from Lorde’s critique of sensation without feeling, Green believes Lane is adopting a Trans* theoretical perspective. According to Green, this is a framework where different forms of desire defy the American imaginary, and instead of maintaining certain binds, women are allowed to “be bold and take risks” (Green p.71). Pornography is often critiqued by anti-porn feminists because of the “degrading” of women in scenes related to the category of Bondage, Discipline, Sadism, and Masochism (BDSM). But what they don’t acknowledge is that there’s a possibility of women achieving pleasure by partaking in this kind of sex or viewing it. What they fail to imagine is what Rubin mentions: “Most people find it difficult to grasp that whatever they like to do sexually will be thoroughly repulsive to someone else, and that whatever repels them sexually will be the most treasured delight of someone, somewhere” (Rubin p.15). In other words, authors like Rubin and Green emphasize removing the line that dictates what kind of sex or porn is proper.

The Case

The Return of the Porn Wars

With the increase of younger folks watching pornography and the defunding of sexual education in schools led to the reemergence of the porn wars. In contrast to the 1980s, porn has now become readily available and free to newer generations. According to a nationally representative survey of adolescents, found that about forty-two percent of adolescents ranging from ten to seventeen have reported being exposed to online pornography, and thirty-seven percent report watching it intentionally (Jhe 2023). Currently, most pornographic websites just require you to check a box claiming that you’re eighteen without requiring identification. In addition, only twenty-eight states mandate sexual education to be taught, and most educators within this area of study aren’t required to have any credentials. As a result, most adolescents are forced to seek sexual education from pornography (Guttmacher 2023). Due to these circumstances, anti-porn feminists and pro-porn feminists debate over whether pornography should be outlawed or if it should be embraced as a form of sexual liberation.

Salucci, Mariavittoria. The History of the Sex Wars, 2021. https://www.nssgclub.com/en/lifestyle/24941/sex-wars-feminism-porn

The anti-porn stance continues to follow the arguments feminists used in the 1980s. The “modern” version of anti-porn feminists like Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon is Gail Dines a professor who is leading an anti-pornography campaign. Dines argues in her book Pornland: How Porn has Hijacked our Sexuality that pornography promotes women-hating because hardcore porn predominantly focuses on the verbal and physical humiliation of women. Some pornography scholars claim that over time hardcore pornography has become the norm as “rough, aggressive, and demeaning acts” make their way to mainstream porn (Shor p.1). Within this type of pornography women are often shown to be, “eager to have their orifices stretched to full capacity” (Dines p. xxiii) which falsely emphasizes that all women find these acts pleasurable. If pornography is now solely revolving around hardcore porn, with the lack of sexual education, adolescents are easily influenced to think that only this type of sex can be pleasurable. In addition, since hardcore pornography has become the norm now, porn stars are actively creating more extreme content to make a profit (Grady 2023). Therefore, anti-porn feminists not only take issue with hardcore pornography being more and more normalized, but also with the commercialization of such porn.

Pro-porn feminists acknowledge that mainstream pornography is inherently flawed but argue that moving to completely outlaw all pornography creates a form of sexual oppression. Linda Williams, a professor at UC Berkeley who specializes in moving image genres like pornography firmly believes that pornography can become a source of sexual liberation. She argues: “If adults consented to making a piece of pornography, even violent pornography, what was wrong with that? What was wrong with the adults who consented to watch it? Were women incapable of enjoying porn themselves?” (Grady 2023). Since pro-porn feminists believe that sexual liberation is a goal of the feminist movement and pornography will continue to thrive, their solution is to reform the industry. The main method for reforming the industry they propose is the creation of feminist pornography in which the performers hold all the power, the categories expand beyond hardcore pornography, and the content is outside of the revolving male gaze. To answer the issue of the growing number of adolescents watching and gaining their sexual education from pornography, pro-porn feminists answer by addressing the state’s flaws in this regard: “In their view, porn has the power to teach them the truth about sex not because the state has failed to legislate, but because the state has failed in its basic responsibility to educate” (Grady 2023). In other words, if adolescents had the proper education on sex, then their brains wouldn’t be so easily influenced by the content within porn.

Women’s Consumption of Porn

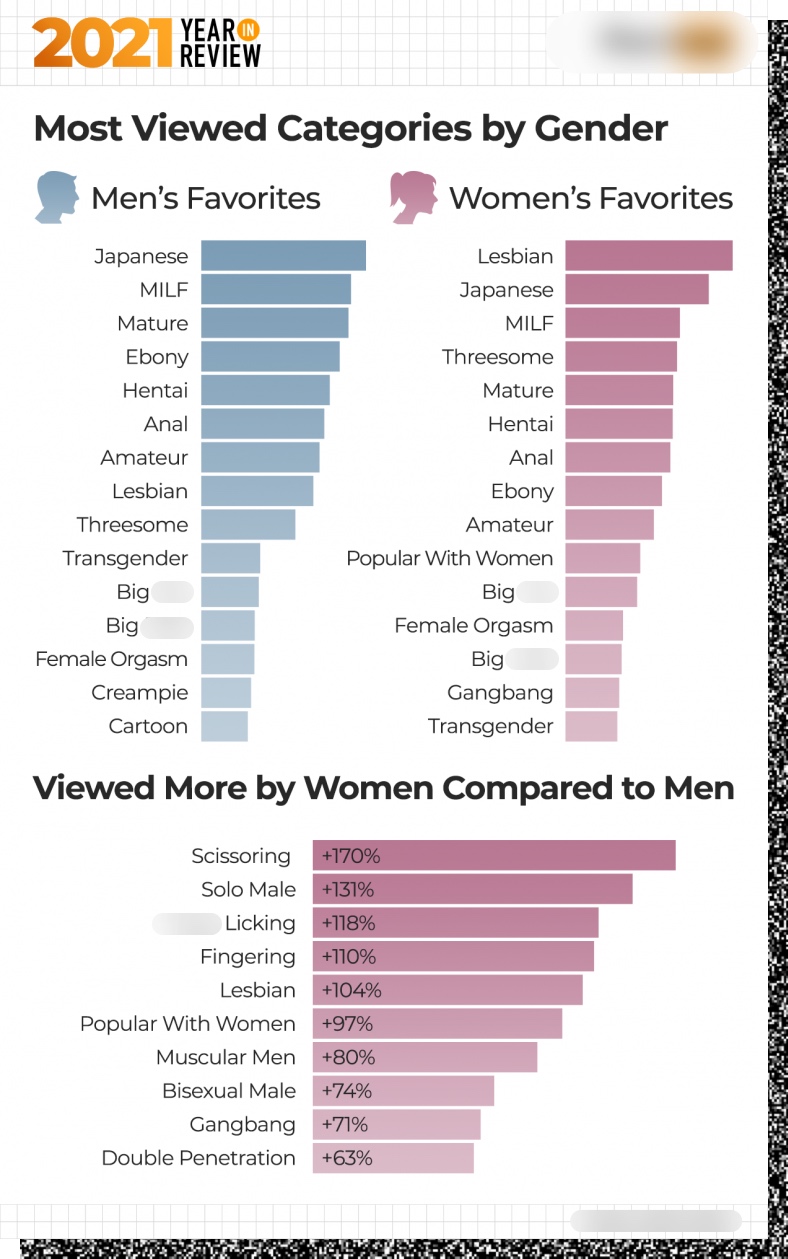

Stats from Pornhub’s 2021 Annual Report insights : https://fightthenewdrug.org/how-do-men-and-womens-porn-site-searches-differ/

Moving away from the negative effects stance on pornography, studies show that porn can have positive effects on women. Although men consume porn twice as much as women, studies show that at least 40.8% of women use pornography for masturbation a few times a year or more and 9.8% use it weekly or almost daily (Johnson et al. 2019). Porn has often been made a taboo issue for women because they are often displayed as passive objects and as a result little has been done to examine their perspectives. The studies that have been done so far find that one of the common benefits of women consuming pornography is the awareness they gain of their sexuality and desires. For instance, Rachel, a woman interviewed about her experience with porn, mentions that porn allowed her to view herself as the erotic subject instead of the object. Rachel states, “I think it helped me learn about my desires, my body, how I should touch myself, things I like, things I didn’t like [. . .] I think I learned to be more confident with my body, with my desires, with the things I want to do, with the things I want the guy to do with me…” (Daskalopoulou p.980). Other women like Peppa who was in the same interview states, “And I think seeing women, masturbating or seeing women having sex, or going out of their way to have sex, I think it could help produce a positive outlook on having sex…” (Daskalopoulou p.980). For these women, porn served as an educational tool, and through porn they learned to identify themselves as erotic subjects and not the erotic objects women are always portrayed as. Furthermore, pornography can simply be a place where women explore fantasies. Another informant Violette, explains:

I have a specific fantasy which has nothing to do with my real actions and life. [Although] I am looking for affection in my sexual experiences [. . .], the porn that I usually choose is [. . .] for example, group sex with 30 men and one woman [. . .] and that is something that helps me to come. So, I choose to watch that. Despite all my actions in real life (Daskalopoulou p.976).

The increasing access to pornography allows women to fantasize about sex that is considered “abnormal” within society but also find pleasure without seeking it in real life. Whether women use pornography for pleasure or education, it becomes a functional tool in their lives for them to find empowerment. Through the exploration of one’s body and sexuality, such as discovering what may be arousing, what it feels like to be aroused, and how and by whom women want to be erotically touched, promotes the ability to find erotic justice (Chesser et al. p.1235). Mikki Van Zyl argues that “[e]rotic justice resonates with the values of dignity and equality that surely, we all yearn for in those aspects of our lives that are life-affirming—love, care, connection with others . . . and our general health and well-being (Van Zyl p.148). Therefore, as women find erotic justice sexually, women may also move to find empowerment in other aspects of their lives as this notion is applicable beyond the bedroom.

Black and White Perspective: Anti-porn Stance vs. Pro-porn Stance (Analysis)

The anti-porn stance often revolves around the extreme cases of porn, and it disregards women’s ability to have any agency or desires of their own. Rich highlighted that “…even so-called soft-core pornography and advertising depict women as objects of sexual appetite devoid of emotional content, without individual meaning or personality…” (Rich p.641). This perspective tends to dehumanize women completely and enforces a misogynist mindset that women are simply passive sexual objects that lack agency. Making these assumptions disregards the fact that women actively choose to or find enjoyment when partaking in the industry. A woman that goes by the stage name Stoya who partakes in the porn industry was asked what her favorite part about the job was. She replied: “I get to show different sorts of sexuality and sexual tastes and acts in what I feel is a pretty freaking ethical and enjoyable way” (Isaacson 2014). Contrary to what many anti-porn feminists emphasize, women are capable of actively choosing to partake in these sexual acts and enjoy their time while doing so. Audre Lorde criticized porn because she believed that porn emphasized “sensation without feeling” but some porn stars claim to find enjoyment, Dylan Ryan a porn star states:

Women don’t have many opportunities to express their sexuality and what is positive for them sexually, and it’s felt empowering to represent myself and my sexuality and know that other women are going to see that and see me enjoying myself, me being present and in my body, and imagine that there is a space for them to be sexual without shame (Isaacson 2014).

If we follow Ryan’s argument, it becomes evident that partaking in pornography isn’t as sterile as Lorde and other feminists make it out to be. If the erotic is the power and knowledge to find pleasure within all parts of one’s life beyond the bedroom as Lorde argues, for porn stars there is a pleasure gained from not only partaking in bedroom activities but also within their job. Gail Dines speaks on the negative effects of porn in her book Pornland, but what many don’t realize is that she provides a one-sided account that disregards the women who enjoy watching porn and partaking in certain sexual acts. For example, the authors of the book review on Pornland argued that: “As feminists, we reject essentialist understandings of women’s sexuality and desire, recognizing that, indeed, some women do enjoy (and are not victimized by) anal and oral sex and that our sexual motives aren’t always intimate and romantic” (Kennedy 2010). Ultimately, before seeking to completely outlaw porn, it is essential to address the gray area of the debate.

Limitations Within the Pro-Porn Argument

Parallel to the anti-porn argument, the pro-porn argument faces its own set of significant limitations that warrant acknowledgment. Professor Dines has declared pornography a “public health crisis of the digital age,” as she refers to the concerning trend of adolescents as young as twelve or even eight years old being exposed to explicit content. Furthermore, according to a UK survey, 44% of adolescent males ranging from ages 11-16 reported that watching online porn has given them ideas about the type of sex they wanted to try (Dines 2020). Consequently, as teens use pornography as their main source of information for sex, they can create unrealistic beliefs and expectations about sex. In the series “Grey’s Anatomy” season 19, episode 3, titled “Let’s Talk Sex” it becomes evident how pornography can be misguiding for teenagers. Within the episode there’s a conversation between a doctor and a teenager discussing sexual education:

Doctor Millin: Penetration is not necessary for mutual pleasure. For starters, most women, or people with vaginas, can’t achieve orgasm through penetration.

Teenage Boy: How come that’s not in porn?

Doctor Millin: Because porn is to actual human sex as the Fast & Furious is to actual human driving. That is to say it bears no resemblance. If you are having sex with your partner, and you are trying to make it look like porn, your partner is experiencing little to no pleasure.

Teenage Boy: I would disagree.

Doctor Kwan: Well, you would disagree because the girls you are with are also making it look and sound like porn (“Let’s Talk Sex” 28:17-28:50).

This dialogue encapsulates the dangers of watching pornography as a teenager without proper sexual education. Lacking adequate guidance and restrictions on readily accessible websites, teenagers may become susceptible to the influence of explicit content. This susceptibility can, in turn, lead to detrimental actions within their real-life relationships.Additionally, even though feminist pornography provides a more realistic alternative to mainstream websites, feminist pornography comes at a cost, “young people making their way to the internet to watch pornography are most likely to go for the free stuff, the MindGeek sites, where the videos they are served are not particularly feminist” (Grady 2023).

Although there are women who enjoy partaking in the porn industry that is not always the case. Jan Villarubia, a former porn actress, talks about her experience in the industry, “I had to do whatever the producer pleased, and I had to accept it or else no pay” (). Like Villarubia, many women in the industry lack the agency to dictate what performances to partake in. Similarly, another porn actress states, “If you don’t fit into those two stereotypes, which is 90 percent of the shoots that we are booked for on set, then all you have going for you is what you’re willing to do…”(Grady 2023). Even if these women are willing to do these acts, they aren’t meaningfully consenting. Furthermore, according to sociologist Kelsy Burke, author of “The Pornography Wars” porn made almost $800 million in 2020, but that money goes to the creators of the websites and not to the actual performers (Grady 2023). Therefore, women like Villarubia find themselves engaging in performances they lack enthusiasm for, often without the guarantee of receiving the promised compensation.

Sexual Correctness

By continuously ignoring the fact that some women find porn, and hardcore porn enjoyable, the Western notion of good and bad sex is reinforced. Pornography has allowed for the various fantasies of all people to be played out free of shame from the rest of society. The anti-porn stance repeatedly attacks pornography because of the category of BDSM without acknowledging that, as Rubin argues: “One need not like or perform a particular sex act in order to recognize that someone else will and that this difference does not indicate a lack of good taste, mental health, or intelligence in either party. Most people mistake their sexual preferences for a universal system that will or should work for everyone” (p.15). Rubin’s and other pro-porn feminists’ ideas challenge the notion of eliminating pornography simply for its hardcore content. Simply because certain feminists may deem this type of sex “wrong” does not mean that it is the same for everyone else. Through the studies of women’s consumption of pornography, it is evident that women have fantasies that may not be desirable for everyone, like the woman who fantasizes about thirty men and one woman. This notion creates a sense of sexual oppression because without porn this type of sex will continue to be stigmatized. As for feminist pornography, this type of porn is often sought out by women to find a more accurate representation of themselves and their desires. But within these sites, so-called “abnormal” desires are also portrayed and by doing so there’s an acknowledgment that women do have the ability to enjoy brutal sex or other forms of sex that anti-feminists prohibit. In other words, women are actively viewing porn to nurture their erotic self and improve other sections of their life:

For Fiona, consumption of Sexual Explicit Material (SEM) for physical ‘release’ went a step further, in that it also allowed her to experience emotional benefits: ‘‘I personally need to get off several times a week, otherwise I’m a cranky bitch. I’m cranky and I have no patience. So that is strictly my reason to watch porn (Chesser et al. p.1241).

Lorde believed that the erotic could be applied to other sections of women’s lives outside the bedroom but a lack of pleasure and joy within the bedroom may impact other aspects of our lives. Without pornography, there’s an increased difficulty in finding one’s pleasures or experiencing one’s fantasies without relying on others. As Jolly Cornwall and Hawkins have argued, women may often ‘‘move from negotiations for orgasms to demands for a guarantee to other rights” (Chesser et al. p.1246). This movement for? women’s erotic justice is associated with the belief that they are entitled to equality within all aspects of their lives. Therefore, instead of removing the erotic from the bedroom, it’s important to analyze how starting in the bedroom can further improve other dimensions in women’s lives.

Conclusion

The pornography debate has been ongoing since the 1980s to determine whether pornography should be outlawed or embraced. The anti-porn stance firmly believes in the outlawing of all forms of pornography as its proponents believe that this industry maintains the sexual oppression of women and it depicts hardcore porn as falsely pleasurable. The other side of this debate though revolves around the idea that banning pornography in its entirety can create a form of sexual oppression since it denies women the ability to explore their sexuality on their own. Furthermore, pro-porn feminists believe that the anti-porn stance fails to acknowledge that women have the ability to enjoy various types of porn even if they are brutal.

Moreover, with the rise in the number of adolescents viewing pornography and the lack of sexual education in schools, the porn debate has risen once again. Anti-porn feminists believe that under these circumstances younger generations are acquiring false information from porn and applying it in their lives. On the contrary, pro-porn feminists believe that reforming the industry is a much better solution to outlawing it completely and they propose addressing the state’s lack of responsibility is the way to address the problem Finally, another important aspect of this topic is the fact that there is little research on women’s consumption of pornography and how they can find empowerment through the viewing of it.

By looking at Adrienne Rich and Audre Lorde’s works, we were able to examine the foundation of the anti-porn debate. Through these authors it becomes clear that their objections to pornography stem from the common notion that pornography promotes women hate because of their subordinate position and the false depiction of true and genuine pleasure. On the contrary, authors like Gayle Rubin and Kai Green, challenge the notion of what counts as sexual correctness. They might not actively take a stance on pornography, but their work allows for the possibility of moving away from what is considered normal. By doing so, pornography no longer becomes a taboo subject, and hardcore sex becomes acceptable along with other types. In this paper, I attempted to present both sides of the debate in depth in order to go beyond the dominant perspectives in the literature. In addition to the arguments used in the porn debate, some data proves that women not only view pornography, but also find empowerment through its use. In fact, women have come to use pornography as a tool to learn about their sexual desires, practice sexual freedom by exploring their fantasies, and find their erotic justice. The analysis seeks to address the limited perspective of the anti-porn stance to argue that there is more that goes into the debate and outlawing pornography on these assumptions can be harmful. Similar to the limitations inherent in the anti-porn argument, the pro-porn argument also reveals its own shortcomings. The advent of feminist porn, while aiming for positive representation, comes at a financial cost and in turn forces people to mainstream pornography. Moreover, younger generations may find themselves more susceptible to establishing unrealistic expectations about sex, and a significant proportion of women in the industry do not report positive experiences.

As I researched this topic, I tried to incorporate both sides of the debate in order to reach my conclusions accurately. Compared to other pro-porn feminists, I acknowledge how deeply flawed the porn industry can be and in no way do I seek to disregard the facts. Still, I don’t believe that outlawing it in its entirety is the best solution. For so long now we have pushed women aside when it comes to sex, porn, and masturbation and we continuously treat them as passive objects. Therefore, my interest in women’s consumption of pornography stems from a desire to portray women as erotic subjects who are capable of enjoying all types of pornography. I firmly believe that in this debate there is a large gray area and it’s not all black and white like many anti-porn feminists make it seem. By setting hardcore pornography outside of the good sex circle, we are abiding by the Western notion of what good sex is (Rubin p13).

When it comes to the issue of pornography as a source of sexual education, I agree with the pro-porn feminists who argue that this is an issue that should be taken up with both the government and the parents of these teenagers. If adolescents had proper sexual education from both their parents and schools, they would have the ability to determine that everything they view in porn isn’t a representation of real life. Finally, another dimension I became aware of while working on this paper was the existence of feminist pornography, which I believe can be a solution for bettering the porn industry. Unfortunately, a lot of these sites cost money which ultimately pushes people to free sites like Pornhub making it difficult to conduct such reform.

Works Cited

Chesser, Stephanie, et al. “Nurturing the erotic self: Benefits of women consuming sexually explicit materials.” Sexualities, vol. 22, no. 7–8, 2018, pp. 1234–1252, https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460718791898.

Daskalopoulou, Athanasia, and Maria Carolina Zanette. “Women’s consumption of pornography: Pleasure, contestation, and empowerment.” Sociology, vol. 54, no. 5, 2020, pp. 969–986, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520918847.

Dines, Gail. Pornland: How Porn Has Hijacked Our Sexuality. Beacon, 2010.

“Ex-Porn Performers Share Brutal Truth about Most Popular Scenes.” Fight the New Drug, fightthenewdrug.org/10-porn-stars-speak-openly-about-their-most-popular-scenes/. Accessed 17 Dec. 2023.

Grady, Constance. “The Return of the Porn Wars.” Vox, 8 May 2023, www.vox.com/the-highlight/23699724/pornography-wars-feminism-pornhub-andrea-dworkin-catharine-mackinnon-amia-srinivasan-kelsy-burke.

Green, Kai M. “Troubling the waters.” No Tea, No Shade, pp. 65–82, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373711-004.

Guttmacher Institute. “Sex and HIV Education.” 19 Sept. 2023, www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education.

Isaacson, Betsy. “Why These 3 Women Chose to Go into Porn.” HuffPost, HuffPost, 7 Dec. 2017, www.huffpost.com/entry/porn-stereotypes_n_5129137.

Jhe, Grace B, et al. “Pornography Use among Adolescents and the Role of Primary Care.” Family Medicine and Community Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Jan. 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9853222/.

Johnson, Jennifer A, et al. “Pornography and Heterosexual Women’s Intimate Experiences with a Partner.” Journal of Women’s Health (2002), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30998084/. Accessed 19 Nov. 2023.

Kennedy, Amanda, and Cheryl Llewellyn. “Book reviews: Xxxtreme content: Why Pornland’s conclusions are hard to swallow Gail Dines, pornland: How porn has hijacked our sexuality. Boston: Beacon Press, 2010. 256 pages, $26.95. ISBN (HBK): 978—0—8070444520.” Sexualities, vol. 14, no. 2, 2011, pp. 257–259, https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607110140020302.

Lorde, Audre. “Uses of the erotic: The erotic as power.” Feminism And Pornography, 2000, pp. 569–574, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198782506.003.0032.

Miller, Stuart. “The Author of ‘The Pornography Wars’ Thinks We Should Watch Less and Listen More.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 25 Apr. 2023, www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2023-04-25/the-author-of-the-pornography-wars-thinks-we-should-watch-less-and-listen-more.

Rhimes, Shonda. “Let’s Talk Sex.” Grey’s Anatomy, season 19, episode 3.

Rich, Adrienne. “Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence.” Feminisms, 1998, pp. 320–324, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192892706.003.0054.

Rubin, Gayle. “Thinking sex: Notes for a radical theory of the politics of Sexuality.” Culture, Society and Sexuality, 2007, pp. 166–203, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203966105-21.

“The Porn Crisis: What We Need to Know about It.” Dr. Gail Dines, 5 Feb. 2020, www.gaildines.com/the-porn-crisis/.

Van Zyl, Mikki. “Taming monsters: Theorising erotic justice in Africa.” Agenda, vol. 29, no. 1, 2015, pp. 147–154, https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2015.1010289.